These Images From 1968 Capture an America in Violent Flux

A one-room show at the National Portrait Gallery is a hauntingly relevant 50-year-old time capsule

:focal(2363x2166:2364x2167)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/77/1c7735c6-3ca7-4db7-bde6-287cfedc2b19/earthrise_large_dpi.jpg)

It was a year of evolution and revolution, one filled with newly galvanized protest movements and civil rights milestones, but also tinged by a war spinning out of control, assassinations, violent protests and a chaotic and dangerous presidential campaign. By the end of 1968, Americans were questioning just what it all meant. Those issues were made all the more existential by the realization that the Earth was nothing more than a tiny ball floating in a vast black space.

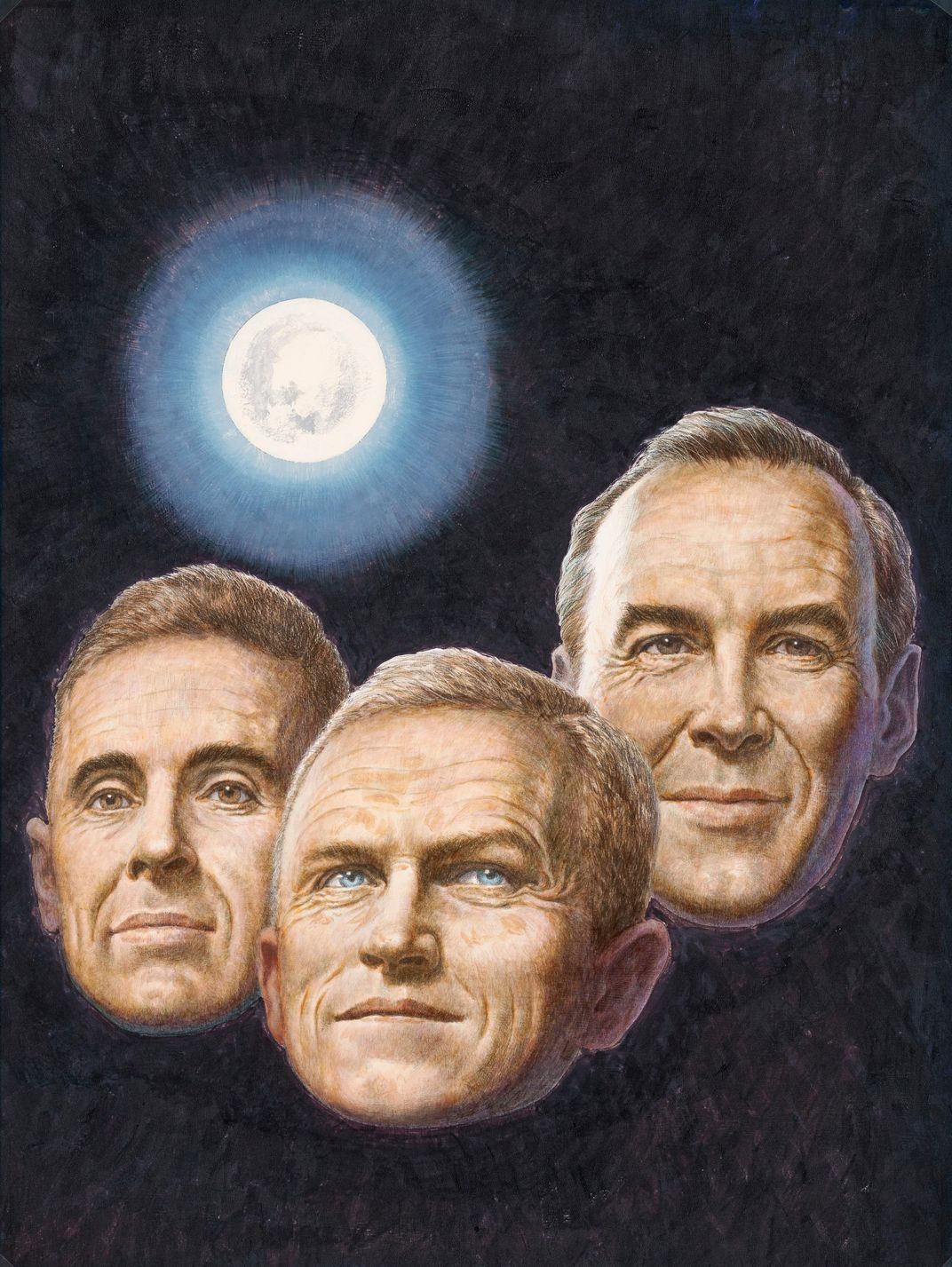

One image helped solidify that notion—it showed a sliver of the planet, taken from the perspective of the moon. That lonesome yet awe-inspiring view, which went on to be seen by millions on TV and in newspapers, is credited with helping to start the environmental movement. It was captured in December by astronaut William Anders during the Apollo 8 mission.

“No one had seen anything like that,” says James Barber, National Portrait Gallery historian and curator of the exhibition, “One Year: 1968, An American Odyssey,” now on view through May 19, 2019.

The iconic Earthrise image sets the tone for the show, which illustrates, through 30 artworks, the highs and lows that America experienced in those tumultuous 12 months. Barber hopes the images—concentrated in one intimate gallery—will help viewers “appreciate the conglomeration of events that occurred in this year,” he says.

The material—primarily photographs and illustrations, many from the NPG’s collection of original artwork used for Time magazine covers—also clearly demonstrates that the issues America was struggling with then seem to be just as pressing today.

America’s youth were questioning politicians and policy, helping to lead the ever-louder cry against an intractable war and what they viewed as a morally and ethically corrupt government. Guns—used in the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, Jr.—became fodder for debate.

“Today’s concepts of leadership, civic engagement, creativity and tenacity derive from those who came before us and the American odyssey that took place over the course of a single year,” says the museum’s director Kim Sajet.

The 1968 show is also a tip of the hat to the gallery itself, which opened in Washington, D.C., during that revolutionary year. “As the national guard patrolled the streets outside to prevent the looting and social unrest in our nation’s capital, the first African-American mayor of D.C., Walter Washington, officiated the opening of what is still to this day the only one of its kind in the United States, the National Portrait Gallery,” says Sajet.

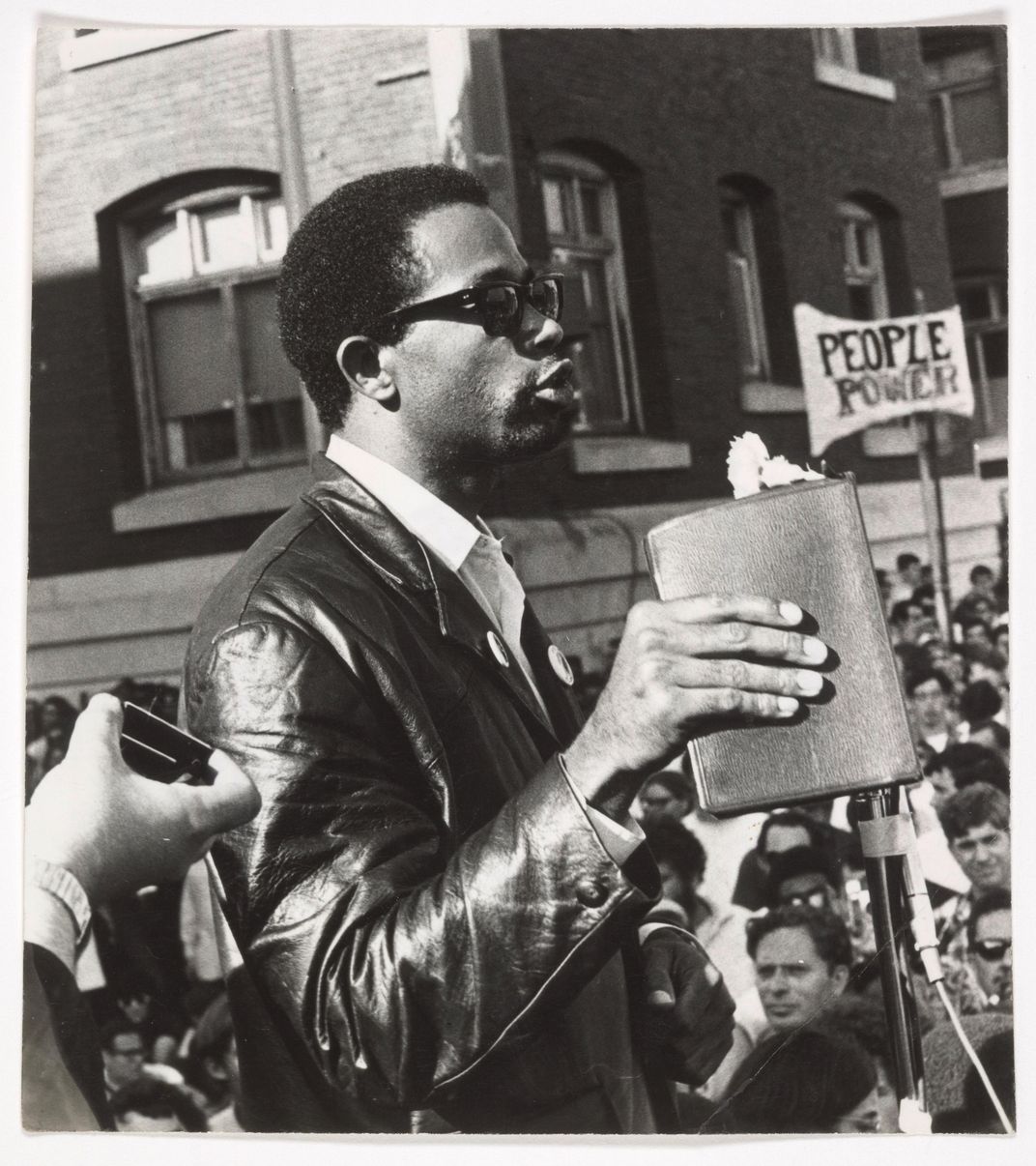

African-Americans had grown tired of the nation’s silence in the face of continued bigotry. Some expressed themselves through art and literature, or through silently raised fists, labor strikes and civil rights marches, while others funneled their frustrations into confrontations with the police or into aggressive, even violent, advocacy movements like the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

The show features several Panther leaders, including a Stephen Shames photograph of Bobby Seale surrounded by his fellow Panthers, and another Shames image of Eldridge Cleaver, who that year had published his critically acclaimed memoir Soul on Ice that delivered a raw and unforgiving depiction of black alienation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/f5/7ff58286-5c4e-43d8-af1f-8b9d90ad6e5b/1968_6.jpg)

Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown, who started as peaceful grassroots activists but joined the Panthers, and the call for a Black Power movement, are portrayed in a James E. Hinton, Jr. photo. Carmichael has a pistol tucked into the waistband of his jeans, while Brown rests a shotgun in the crease of his hip; both appear ready to mobilize.

Women asserted their right to equality. A prominent defender of racial and gender equality, Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm, became the first African-American woman elected to Congress in 1968. In a photograph included in the show, famed portraitist Richard Avedon gives us a straight-ahead view of Chisholm in a belted military-style suit, her soft eyes belying her battle-hardy soul.

The American-born migrant worker César Chávez, who along with civil rights activist Dolores Huerta had founded four years earlier the United Farm Workers union, joined Filipino workers in a nationwide boycott of California grapes. Richard Darby’s March 1968 black and white photograph depicts Robert F. Kennedy sitting with Chávez, appearing quite weakened following his 25-day hunger strike to protest the violence against workers on strike.

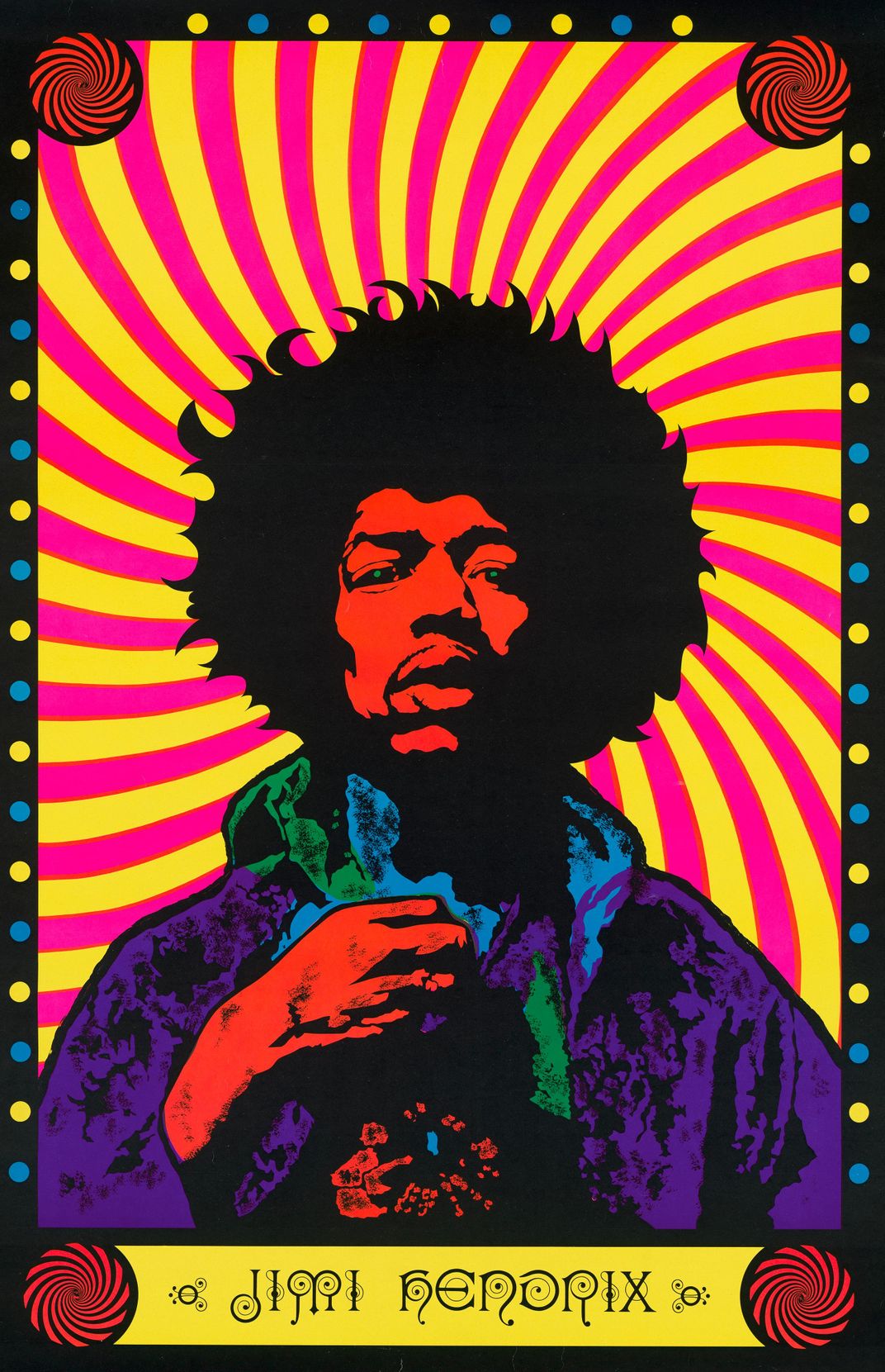

Young people urged Americans to question the establishment and embrace their counterculture, hippy lifestyle. Musical artists such as Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead gave voice and power to the movement. Irving Penn’s gorgeous platinum palladium print groups them together as one big family, conjuring up the Haight-Ashbury communes that generated those bands and many more.

Violence was increasingly brought home to American living rooms—through television, which sent its correspondents to the streets of Washington, Detroit and Chicago to witness riots after the King assassination, and to the fields of Vietnam. On February 27, 1968, venerated CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite declared that the conflict was unwinnable, a stalemate. A small portrait of U.S. Army Lieutenant William F. Calley gives a quiet nod to the Vietnam quagmire. Eventually, Calley was criminally convicted for helping to conduct the massacre of some 500 civilians in the village of My Lai in March, making Calley a potent symbol of that war’s enduring calamities.

The war ended the Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, a moment captured in a Pierre De Bausset photograph of LBJ and his wife Lady Bird, sitting on a couch in their private White House quarters, watching a taped replay of the March press conference after Johnson had announced that he would not seek reelection.

After Johnson’s decision, the Democratic field quickly filled with a bevy of contenders, including RFK. In June, Sirhan Sirhan shot and killed him in a Los Angeles hotel for reasons that are still not known.

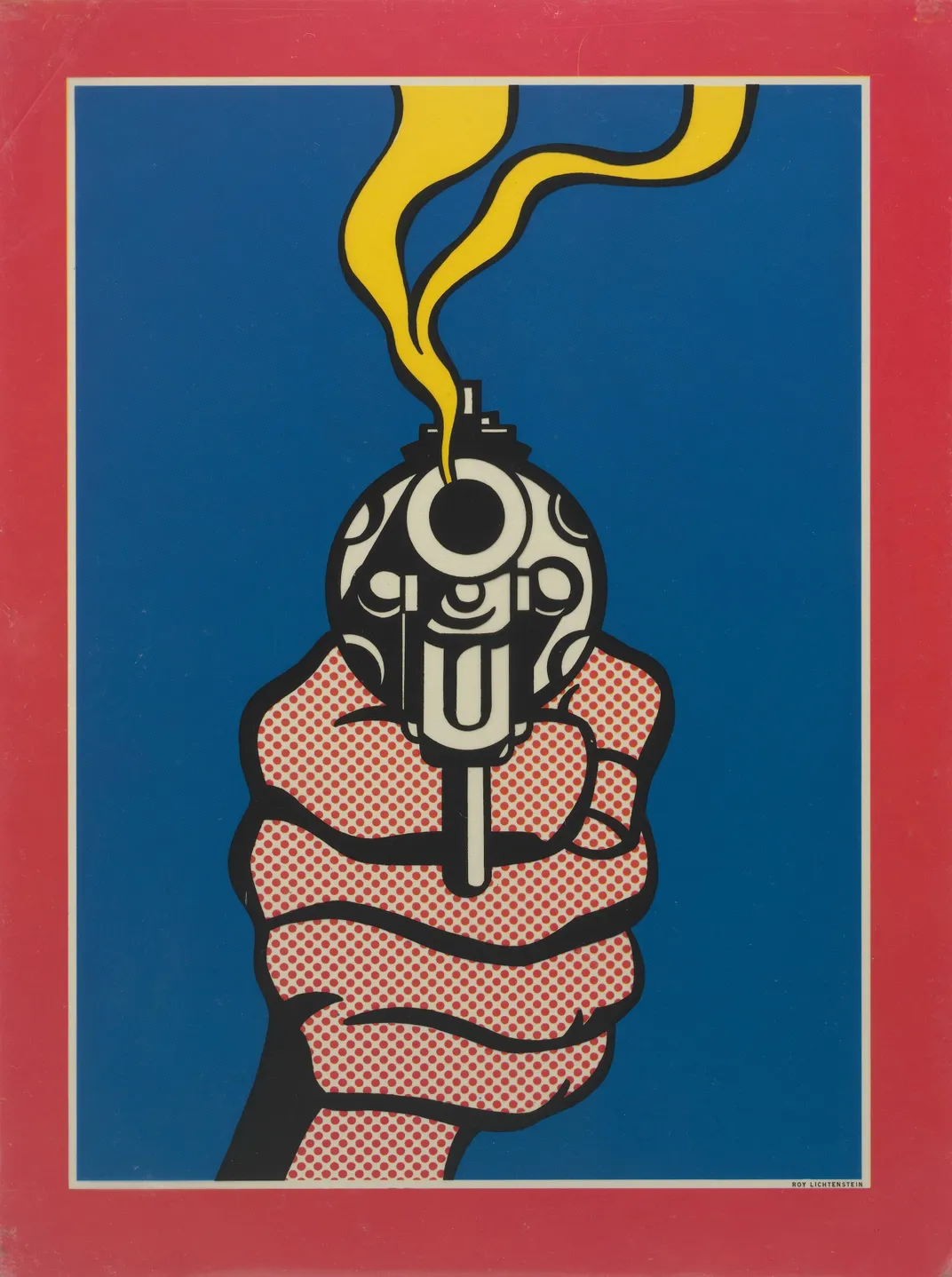

But the assassination—and the April slaying of Martin Luther King, Jr—led to the potent June 21 Time magazine cover by pop artist Roy Lichtenstein included in the show. The screenprint image entitled Gun in America holds powerful resonance—a hand grips a smoking revolver that is pointed directly at the viewer.

The cover represented a tipping point, says Barber. Up until 1968, the National Rifle Association (NRA) had primarily been focused on gun safety and using firearms for sport. The assassinations prompted new, more restrictive gun control legislation, which LBJ signed into law in October. The NRA was “beginning to become the lobbying organization that has become the power that we know today,” says Barber.

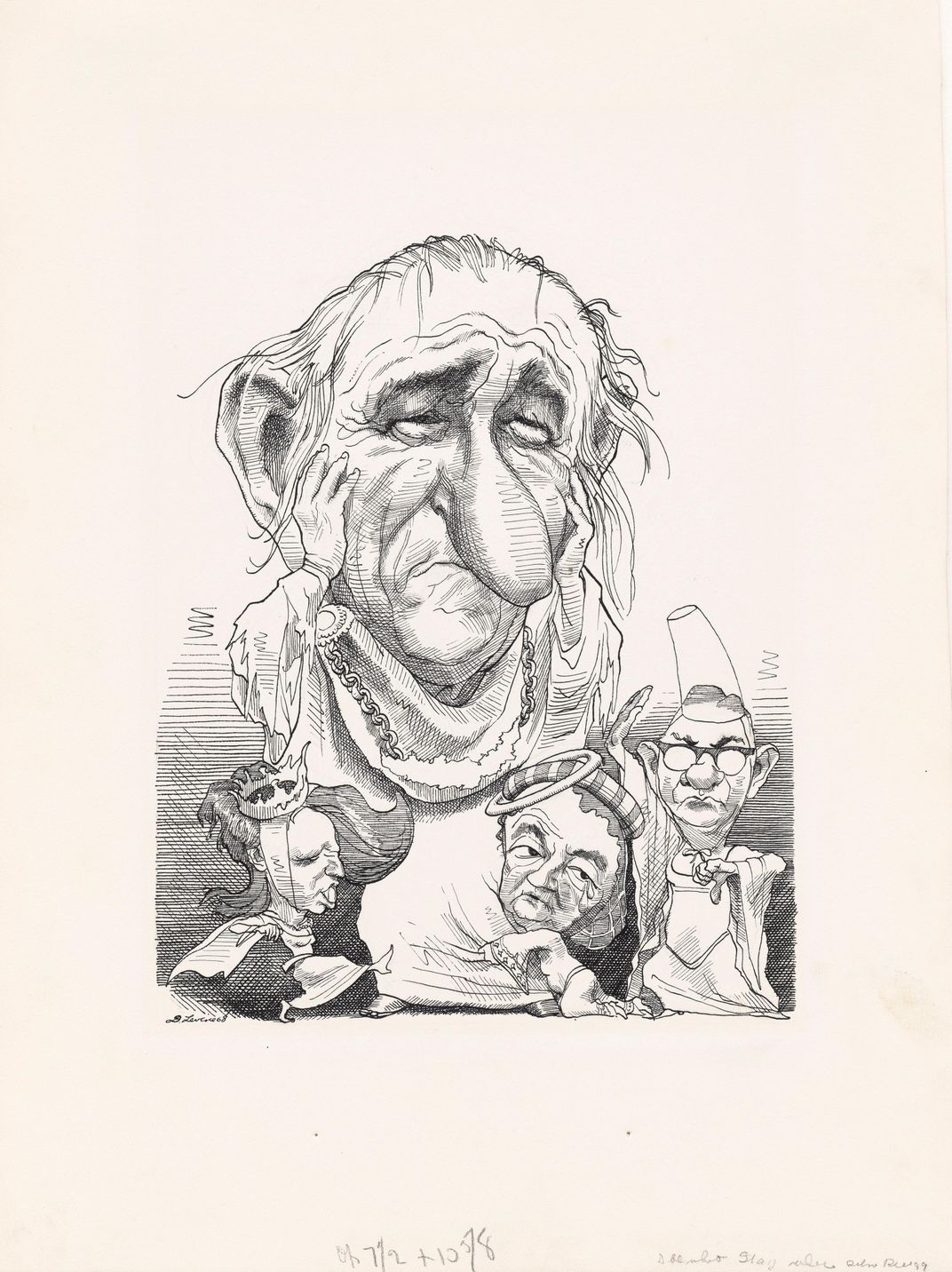

Ultimately, Hubert Humphrey, Jr. and Edmund Muskie were selected as the Democratic party’s nominees, over the objection of thousands of anti-war protesters who flooded the streets of Chicago during the 1968 convention. They wanted their anti-establishment candidate, Eugene McCarthy. Mayor Richard J. Daley, anticipating the protests, fortified much of the convention area and called 20,000 local, state and federal law officers into action. Hundreds of demonstrators, journalists and physicians were beaten, gassed and otherwise subdued, creating an indelible image of America at war with itself, and a Democratic party out of touch with a huge portion of its potential voters.

That tragedy is illustrated by a September 6, 1968 Time cover. Artist Louis Glanzman drew a conventional portrait of Humphrey and Muskie side by side, but cut a bloody gash across the background. Daley’s face looms from within that red wound.

Even as America mourned its tragedies, it celebrated its triumphs, especially in sports. Legendary National Football League coach Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers won the first two Super Bowls in 1967 and 1968. The show features Boris Chaliapin’s 1962 Time cover of a spectacled Lombardi, coolly surveying the field with the crowd at his back. And there’s Peggy Fleming, the only American athlete—in any sport—to win an Olympic Gold medal at the Winter Olympics held in Grenoble, France that year. The 19-year-old amateur skater wearing the neon green costume from her powerful performance made the cover of the February 19 issue of Sports Illustrated and many others.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/56/8e56686e-d11a-4163-89b1-fea0b7bfe379/1968_10.jpg)

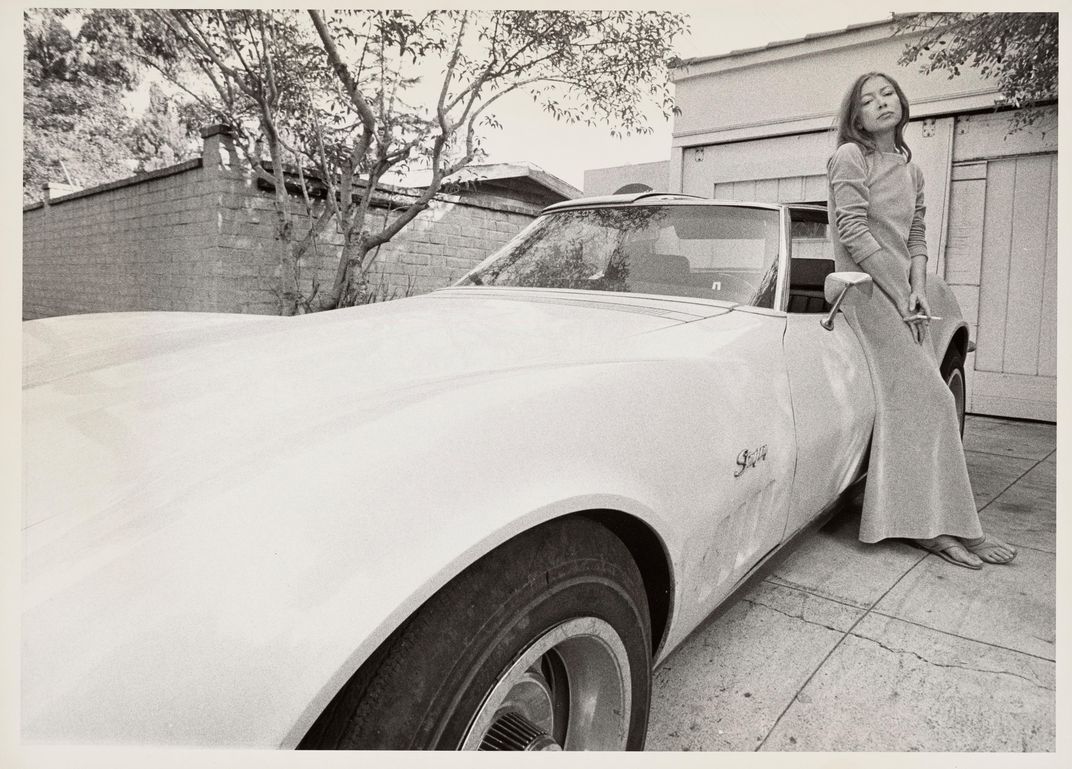

The Olympics provided another touchstone for Americans that year, especially African-Americans. At the summer games in Mexico City, American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos won gold and bronze in the 200-meter race. As they stood on the medal platform with the national anthem playing, they each raised a fist in a Black Power salute, signaling to the nation and the world their stance against racial oppression. The fist—along with beads and scarves they wore to symbolize lynchings—were planned. The image in the exhibition—taken by an unknown photographer—prompted a public reaction that mirrors today’s debates surrounding the NFL players’ National Anthem protests.

Walter Kelleher’s photograph of Arthur Ashe, another black athlete in the limelight that year, depicts the tennis player serving while on his way to his five-set win in the U.S. Open final of 1968, becoming the first African-American to take the title and the first black man to win a Grand Slam. And he did it while he was still an amateur.

Ashe, too, felt he had a duty to speak out about injustices, and his brand of activism included protesting South Africa’s apartheid and advocating for people with AIDS—a disease that would tragically take his life after he contracted it from a blood transfusion.

So many of the images taken half a century ago bear relevance as if 1968 was the year that the nation began to move from its adolescence to its adulthood, maturing a deeper understanding of the profound forces shaping it and challenging it.

"One Year: 1968, An American Odyssey," curated by James Barber, is on view at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. through May 19, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/77/1c7735c6-3ca7-4db7-bde6-287cfedc2b19/earthrise_large_dpi.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)