In Lines of Long Array, 12 Poets Reflect on the Civil War

The National Portrait Gallery commissioned 12 modern-day poets to consider the harsh realities of battles that continue to haunt

On October 1, the National Portrait Gallery will publish Lines in Long Array. A Civil War Commemoration. Poems and Photographs. Beautifully designed and printed, Lines in Long Array contains 12 new poems commissioned from some of the most prominent poets writing in English, including: Eavan Boland, Geoff Brock, Nikki Giovanni, Jorie Graham, John Koethe, Yusef Komunyakaa, Paul Muldoon, Steve Scafidi, Michael Schmidt, Dave Smith, Tracy Smith and C.D. Wright.

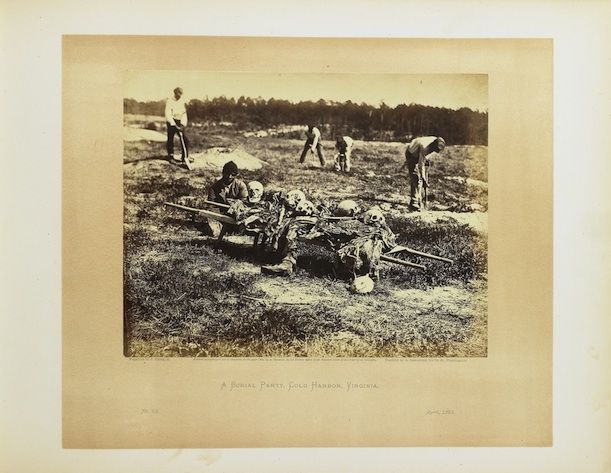

Along with the poems are landscape photographs by Sally Mann. Accompanying this contemporary work, are poems and photographs from the Civil War era itself.

The title is an adaptation to the first line of Walt Whitman’s poem “Cavalry Crossing a Ford,” a poem that is included in the book. “Lines”, of course, refers to both the ranks of troops and to the lines written by the poets, and is taken from Whitman’s description of the troops deploying across a stream: “A line in long array, where they wind betwixt green islands;/ They take a serpentine course—their arms flash in the sun—Hark to the musical clank. . . ”

The intention of the editors, myself and former Portrait Gallery curator Frank Goodyear, was to pay tribute to the “readers” that were created during the war both to spur the war effort and to raise money to treat the wounded. Also, as cultural scholars, we were interested in how a modern “take” on the war would compare and contrast with literature and art produced while it was being fought. Truth be told, although the Civil War is of immense importance in the history of the United States, it has only rarely appeared as a subject in our culture.

It’s as if the war was so terrible and its effects so huge, that artists have turned away from it, treating it only indirectly and at a distance; so art historian Eleanor Harvey has argued in her brilliant art exhibition, The Civil War and American Art, an exhibition that debuted at the Smithsonian American Art Museum last November, before traveling to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Modernist poetry has tended to explore the psychology and activities of the individual self, rather than topics drawn from history and public life. John Koethe, asked to reflect on his contribution to the project, wrote that he’d never really considered writing historical poems. “I’m primarily thought of as a poet of consciousness and subjectivity.” But the encounter with the problem of an historical subject—and a gigantic one at that—seemed to galvanize Koethe as it did the other poets, because engaging in the exercise was a way of getting beyond the individual. Koethe continues: “I’d been thinking a lot about the Civil War anyway, and the idea that so much of what we think of as peculiar to our own lives and time is really an echo of a history we don’t fully grasp, is what is behind

In commissioning the poets, we set no rules or confined our contributors to any subject matter. The results are, without exception, works that are deeply considered, well wrought (to use a 19th-century word) reflections on topics ranging from an American diplomat in London by Michael Schmidt to Yusef Komunyakaa’s amazing “I am Silas,” a piece that recreates the journey (and final betrayal) of a slave who went to war to fight alongside his Georgian master.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/71/e57187cf-8ace-40eb-89c4-8869fdd6334a/david-ward_npg1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/07/c307e16e-6ba4-474b-a24d-3a58268d5357/9781588343970web.jpg)

C.D. Wright reflects that she attempted to reach back to her Ozark, Arkansas, ancestors in her poem, taking as her subject a poor farmer who had nothing to do with slavery and just wanted to live independently: “I had never tried to mentally summon and isolate an individual circumstance. . .just another lump in the carnage.”

It would take too long to summarize all the poems here; that’s what reading it is for. But it is that sense of reaching back to re-consider history and memories that we, both as individuals and as a nation, avoided or repressed (as Dave Smith writes about the war, “I couldn’t hold on to it”) and connect it with the present that animates Lines in Long Array. That re-creation of experience, which runs through all of the poems, finds explicit political expression in Nikki Giovanni’s poem, placed as the last one in the volume, that asks us to consider the costs of war, itself, from the epic of Ulysses to Iraq.

I think Eavan Boland’s summary captures the spirit we hoped to achieve when we started out, that the project was “a way of re-thinking memory and history. There just seems something so poignant and respectful in having the poems of a present moment reach back to meaning that were once so large, so overwhelming they almost defied language.”

Dave Smith, in an extended and moving examination of the interplay of past and present, history and tradition, writes that “the poems in project so utterly show, that we cannot resign from but only keep trying to feel accurately, honestly, and with some evolving comprehension” how the past haunts our present.

Or as that old fox William Faulkner put it, “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” But as Americans, always rushing forward, we have too frequently failed to acknowledge how the past shapes us in ways that we don’t even try to understand. Lines of Long Array, in some small way, is an attempt to measure the enduring impact of the immeasurable consequences of the Civil War. And if this is too sententious and overblown a claim for you, at the very least Lines in Long Array contains some very fine writing that is well worth reading.

To celebrate Lines in Long Array, the National Portrait Gallery will hold a reading on November 16th at which the poets will debut their poem, read several others related to it on the topic of the war, and participate in a round-table discussion about the act of writing a work of art that engages history.