A Dozen Indigenous Craftsman From Peru Will Weave Grass into a 60-Foot Suspension Bridge in Washington, D.C.

The ancient technology used lightweight materials to create soaring 150-foot spans that could hold the weight of a marching army

As much as maize, or mountains, or llamas, woven bridges defined pre-Columbian Peru. Braided over raging rivers and yawning chasms, these skeins of grass helped connect the spectacular geography of the Inca empire: its plains and high peaks, rainforests and beaches, and—most importantly—its dozens of distinct human cultures.

Now a traditional Inca suspension bridge will connect Washington, DC to the Andean highlands. As part of the Smithsonian’s upcoming Folklife Festival, which focuses on Peru this year, a dozen indigenous craftsmen will weave together grass ropes into a 60-foot span. It will be strung on the National Mall parallel to 4th Street Southwest, between Jefferson and Madison Avenues, where it will hang from several decorated containers (in lieu of vertical cliff faces) and hover—at its ends—16 feet above the ground. It should be able to hold the weight of ten people.

“One of the major achievements of the Andean world was the ability to connect itself,” says Roger Valencia, a festival research coordinator. “How better to symbolize ideological, cultural and stylistic integration than by building a bridge?” The ropes are now ready: the mountain grass was harvested last November, before the Peruvian rainy season, then braided into dozens of bales of rope and finally airlifted from Peru to America.

The finished bridge will become part of the National Museum of the American Indian’s collections. One section will be featured in a new exhibition, “The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire,” while another length of bridge will travel to the museum’s New York City location in time for the fall 2016 opening of the children’s imagiNATIONS Activity Center.

For native Peruvians, traditional bridge-building is an important tie not only to new people and places, but also to the pre-colonial past.

“I learned it from my father and grandfather,” says Victoriano Arisapana, who is believed to be among the last living bridge masters, or chakacamayocs, and who will be supervising the folklife project. “I lead by birthright and as the heir to that knowledge.”

His own son is now learning the techniques from him, the latest in an unbroken bloodline of chakacamayocs that Arisapana says stretches all the way back to the Incas, like a hand-twisted rope.

The Incas—who, at the height of their influence in the 15th century, ruled much of what is now Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia and Chile as well as parts of Colombia—were the only pre-industrial American culture to invent long-span suspension bridges. (Worldwide, a few other peoples, in similarly rugged regions like the Himalayas, developed suspension bridges of their own, but Europeans didn’t have the know-how until several centuries after the Inca empire fell.) The Inca likely rigged up 200 or more of the bridges across gorges and other previously impassable barriers, according to analysis by John Ochsendorf, an architecture scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Though anchored by permanent stone abutments, the bridges themselves had to be replaced roughly every year. Some of them were at least 150 feet long and could reportedly accommodate men marching three abreast.

Ochsendorf believes that Inca bridges may have first been developed in the 13th century. The engineering breakthrough coincided with—and likely enabled—the rise of the empire, which maintained a sprawling road network (the subject of “The Great Inka Road” exhibition) that united previously isolated cultures under Inca rule.

The bridges allowed for many Inca military victories: Inca commanders would send their strongest swimmers across a river so building could begin from both sides. But the exquisite structures apparently so dazzled some neighboring tribes that they became vassals without any bloodshed. “Many tribes are reduced voluntarily to submission by the fame of the bridge,” wrote Garcilaso de la Vega, a 16th-century historian of Inca culture. “The marvelous new work seemed only possible for men come down from heaven.”

The invading Spanish were similarly amazed. The Andean spans were far longer than anything that they’d seen in 16th-century Spain, where the longest bridge stretched only 95 feet. The Incas’ building materials must have seemed almost miraculous. European bridge-building techniques derived from stone-based Roman technology, a far cry from these floating webs of grass. No wonder some of the bravest conquistadors were said to have inched across on hands and knees.

“The use of lightweight materials in tension to create long-span structures represented a new technology to the Spanish,” Ochsendorf writes, “and it was the exact opposite of the 16th-century European concept of a bridge.”

Ultimately, the bridges—and indeed, the whole meticulously maintained Inca roadway system—facilitated the Spanish conquest, especially when it became clear that the bridges were strong enough to bear the weight of horses and even cannons.

Despite the Inca bridges’ utility, the Spanish were determined to introduce more familiar technology to the Andes landscape. (Perhaps they weren’t keen to swap out each woven overpass every year or two, as the Inca carefully did.) In the late 1500s, the foreigners embarked on an effort to replace the grass suspension bridge over Peru’s Apurimac River with a European-style stone compression bridge, which depended on a masonry arc. But “to construct a timber arch of sufficient strength to support the weight of stone over the rushing river was simply beyond the capacity of colonial Peru,” writes Ochsendorf. “The bridge construction was abandoned after great loss of life and money.”

The colonists wouldn’t be able to match the Inca technology until the Industrial Revolution two hundred years later, with the invention of steel cable bridges. Some of traditional grass bridges remained in use until the 19th century.

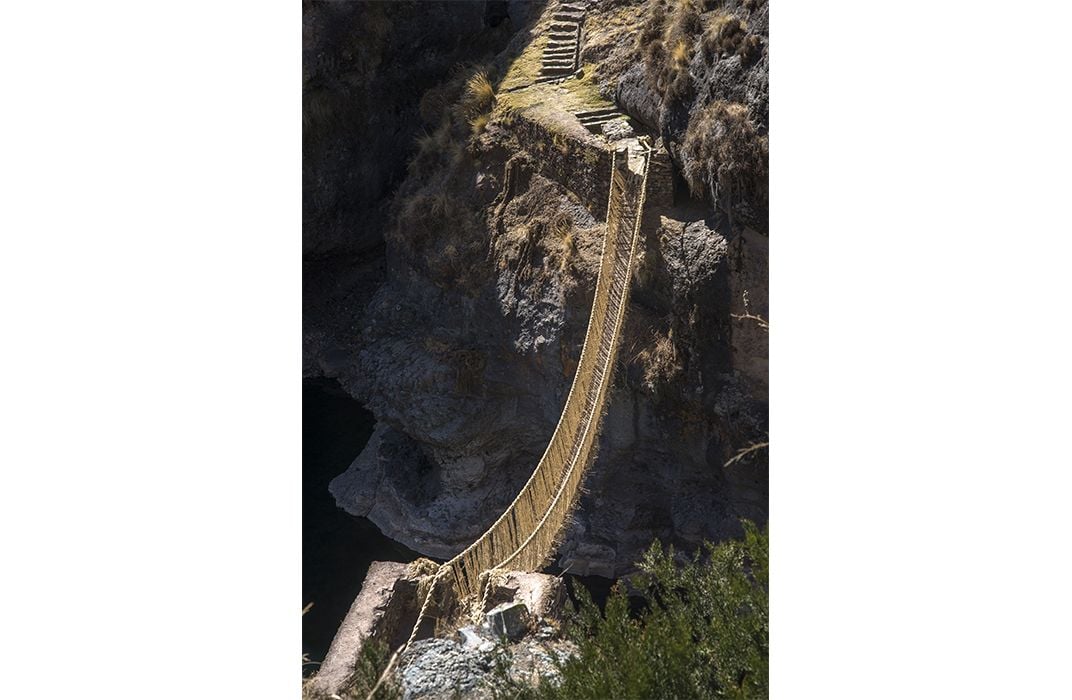

An Inca rope bridge still hangs over a canyon near the highlands community of Huinchiri, Peru, more than a four-hour’s drive from the capital city of Cusco. It is one of just a handful remaining. This is the bridge that Arisapana’s family has overseen for five centuries, and it’s similar to the one to be built on the National Mall.

“The bridge is known worldwide,” Arisapana says. “Twenty people could cross it together carrying a large bundle.”

The old bridge stands near a modern long-span steel bridge, built in the late 1960s and typical of the sort that eventually made the Inca bridges obsolete. Unlike a handmade grass bridge, it doesn’t need to be rewoven every year because of exposure to the elements, with last year’s masterpiece discarded.

Yet Arisapana says his community will build a new grass bridge every June.

“For us, the bridge is the soul and spirit of our Inca (ancestors), that touches and caresses us like the wind,” he says. “If we stop preserving it, it would be like if we die. We wouldn’t be anything. Therefore, we cannot allow our bridge to disappear.”

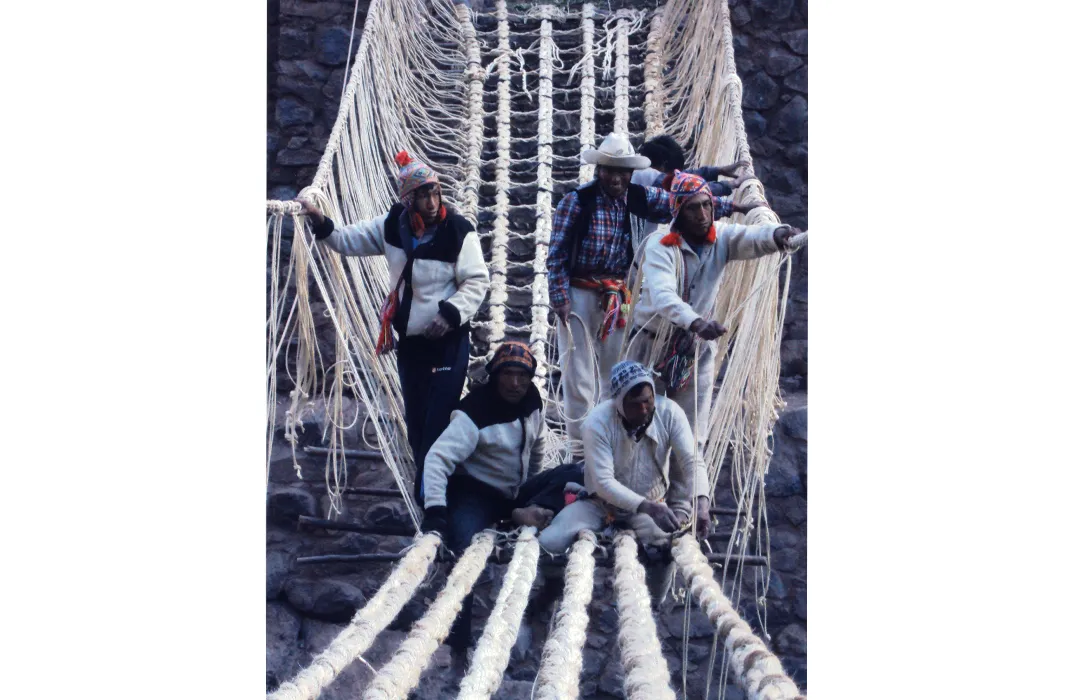

Raw materials probably varied according to the local flora across the Inca empire, but Arisapana’s community still uses ichu, a spiky mountain grass with blades about two feet long. The grass is harvested just before the wet season, when the fiber is strongest. It is kept damp to prevent breakage and pounded with stone, then braided into ropes of varying thickness. Some of these, for the longest Inca bridges, would have been “as thick as a man’s body,” Garcilaso claims in his history. According to Ochsendorf’s testing, individual cables can support thousands of pounds. Sometimes, to test the ropes on site, workers will see if they can use it to hoist a hog-tied llama, Valencia says.

To do everything by himself would take Arisapana several years, but divided among community members the work takes only a few days.

“We have a general meeting beforehand,” he says, “and I remind (the people) of each person, family and community’s obligations, but they already know what their obligations are.” The bridge-raising becomes a time for celebration. “The young people, the children, and even the grandchildren are very happy…they are the ones that talk and tell the story of how the bridge was built by our Inca ancestors, and then they sing and play.”

The old Inca bridge style differs from more recent versions. In modern suspension bridges, the walkway hangs from cables. In Inca bridges, however, the main cables are the walkway. These large ropes are called duros and they are made of three grass braids each. The handrails are called makis. Shorter vertical ropes called sirphas join the cables to the railings and the floor of the bridge consists of durable branches.

The bridge on the National Mall will be made of hundreds of ropes of varying thicknesses. The math involved is formidable.

“It’s like calculus,” Valencia says. “It’s knowing how many ropes, and the thickness of the ropes, and just how much they will support. They test the strength of the rope, every piece has to go through quality control, and everything is handmade.”

Even for those fully confident in the math, crossing an Inca rope bridge requires a certain courage. “You feel it swaying in the wind,” Valencia recalls, “and then all of a sudden you get used to it.”

“Our bridge…can call the wind whenever he wants to,” Arisapana says. Traditionally those who cross the dizzying Andes spans first make an offering, of coca, corn, or “sullu,” a llama fetus. “When we don’t comply…or maybe we forget to demonstrate our reverence, (the bridge) punishes us,” he says. “We could suffer an accident. That’s why, to do something on the bridge or to cross on it, first one must pay respects and offer it a plate.”

Even tourists from other countries visiting his remote village know to not to approach the bridge empty-handed. “We ask our visitors to ask permission and give an offering…at least a coca—that way they can cross and come back without any problems.”

Visitors will not be permitted to cross the Folklife Festival’s bridge, but perhaps an offering can’t hurt.

The bridge builders—who are accustomed to receiving curious visitors back home, but who have never traveled to the United States—are pleased that their ancient craft is carrying them to new lands.

“All of them are very excited,” says Valencia. “They are going to a different world, but their own symbol of continuation and tradition, the bridge, is the link that connects us.

“The bridge is an instrument, a textile, a trail, and it’s all about where it takes you.”

The annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival featuring Perú: Pachamama will be held on June 24–28 and July 1–5 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. “The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire” will be on view at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian through June 1, 2018.

The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/5c/915c7133-6d42-4fe6-af75-37d147cafd16/img075web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/d5/7cd5ccbe-ff9f-439c-9d83-1d8274214440/img099web.jpg)