Inspire Your Toddler’s STEM Career With This ‘Goodnight Moon’ Parody

Astronomer Kimberly Arcand releases her new children’s book ‘Goodnight Exomoon’

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/7d/cb7d7626-80eb-4d8f-a987-04712a5f3d0d/1005760_finalmechs-3.jpg)

Kimberly Arcand looks at the stars for a living. A visualization scientist for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Arcand has made it her life’s work to help tell the stories of space.

Her job is to translate the binary coded astronomical data delivered from technology like the Chandra telescope into glowing, spinning, awe-inspiring images and models of objects in space. Arcand’s visuals enable us to make sense of the vast universe.

Which is why it’s no surprise that Arcand, a storyteller at heart, moonlights as a science writer. Having authored several astrophysics nonfiction books over the years, Arcand recently turned her attention to children’s books. She released, along with co-author Lisa Smith, An Alien Helped Me with My Homework in February, and this summer, her latest, Goodnight Exomoon made its debut. An “astronomical parody,” Goodnight Exomoon takes the classic children’s book Goodnight Moon and explores planetary science in a way that is relatable for the very young.

The idea, Arcand says, was born when her own children, now teenagers, were young toddlers refusing to nap. “I would read for hours to try to get them to go to sleep and they loved Goodnight Moon and [one afternoon] I could not imagine reading Goodnight Moon again so I started riffing on it,” says Arcand. She wrote down one of the versions of her playful parody, then put it in a drawer where it stayed for nearly a decade.

Arcand remembers being fascinating by the idea that someday we’d be able to view exomoons, but thinking how long it would be before that happened. At the time, exomoons, or extrasolar moons—those moons that orbit a planet outside of our own solar system, or exoplanets—were something astrophysicists knew about, but had never captured data from. NASA's Kepler and TESS telescopes have detected nearly 4,000 exoplanets since 2009, but until about a year and a half ago, had never described an exomoon.

Goodnight Exomoon (Smithsonian Kids Storybook)

A modern scientific twist to a beloved bedtime favorite filled with vibrant colors and space science fun!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/02/40026be7-5458-48a0-8947-8d61732b52ee/kim-brittannytaylor-19kk.jpg)

Then, in 2018, scientists found what they believed was the first exomoon orbiting the exoplanet known as Kepler-1625b. “We knew that this field would be burgeoning at some point, but I didn't think exomoons were going to be on the horizon quite so soon. With that first exomoon candidate, it reminded me that I had written the story, and that it really hadn’t been that long,” says Arcand.

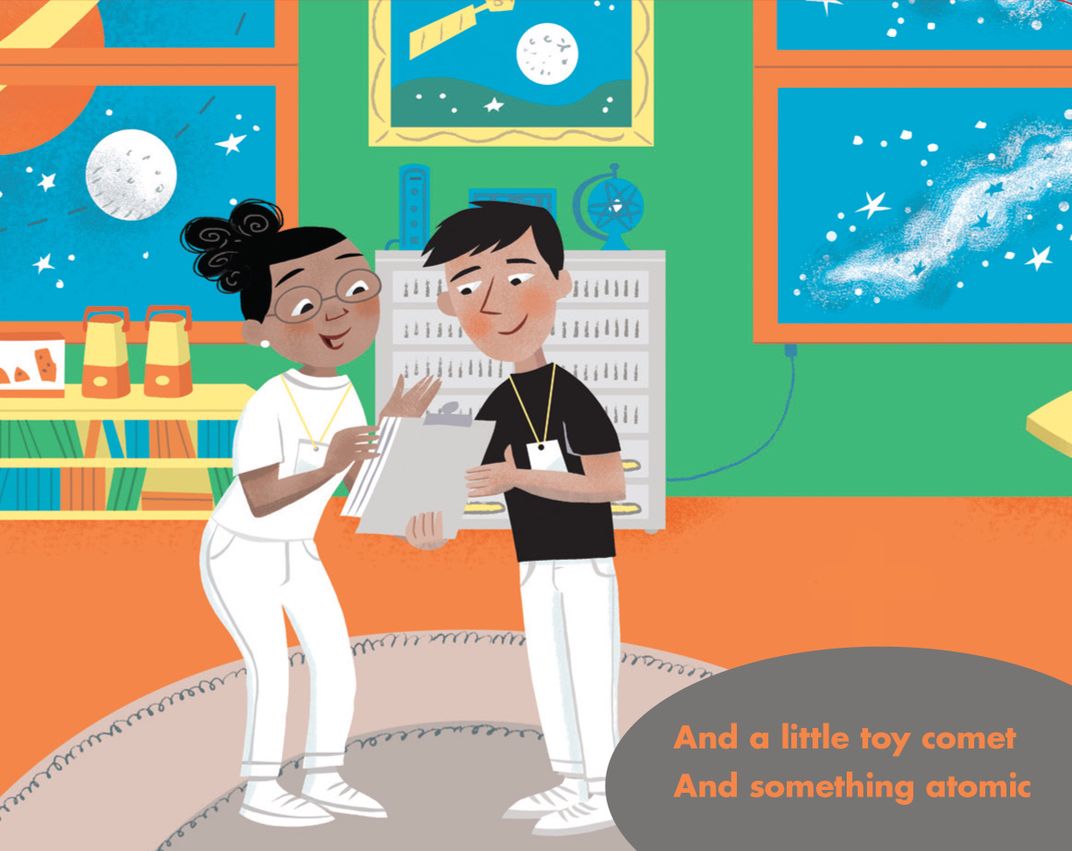

So, the scientist pulled her would-be book out of the drawer and teamed up with illustrator Kelly Kennedy to bring it to life. “In the great telescope room there was a telephone, an atmospheric balloon, and a picture of a satellite flying by the moon. . .” begins the story, setting young readers in a room inspired by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory that houses a giant antique refractor telescope. The story goes on to introduce children to some of the more modern tools that astronomers use, like accelerometers, micrometers and satellites, teaching them about astronomical objects like comets and exomoons.

“We wanted it to be respectful of the original because I know Goodnight Moon by heart—that's how many times I've read it to my children and my niece before them—so it was important to me to be respectful of the original, because it's such a classic story, but to just raise the geekiness factor a step or two,” says Arcand, who worked with Kennedy to hide what she calls “Easter eggs” throughout the book’s illustrations. A photograph on the scientist’s desk in the great telescope room depicts Arcand’s son and daughter; photos on the wall include a picture of a black hole and Chandra’s image of the M87 galaxy; and a space shuttle that is modeled after the Columbia shuttle that launched Chandra into space makes an appearance.

Arcand hopes the book will be a delight for “space geeks,” like herself, but also that it will inspire children and especially young girls to see the field of science as one that is approachable.

This desire drives Arcand’s scientific work, as well. When not penning parodies, Arcand spends her time making complex concepts and theories more accessible to a variety of audiences, from fellow researchers, to students to the general public.

When the Chandra X-ray telescope views an object in space, it sees photons of energy emitted from those objects and records information about them via binary code. When the data reaches Arcand, it is her job to translate the ones and zeros representing aspects like time, position and energy levels into “readable” information. She does this using various techniques, such as creating color maps that articulate different energy levels, for example. Arcand says she tells the story of science, letting the data determine what format that story will ultimately take, whether it turns out to be a 3-D model, print, virtual reality experience or soundscape. Thanks to Arcand and her colleagues and students, we are able to recognize colliding galaxies, merging black holes, exploding stars and stellar nurseries.

“Translation is just everything to me because, clearly, if you're looking at an X-ray image of an exploded star, that's not something you could ever see with human eyes, even if it was close enough to see,” she says. “You have to have a process of translation in there. Taking that translation a step further to bring it into a multimodal space for users of different needs has become really important to me on a personal level.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/13/2f13eb07-4fc5-45ba-80d2-a6a864984244/img_4631_arcand.jpg)

Arcand and her team are just beginning to experiment with holograms as a form of data visualization, which, she says, could be particularly useful because virtual and mixed reality models depend on wearing headsets, which, especially in the age of COVID, can raise health and accessibility issues.

Data sonification, or creating audio out of astrophysical information, is another way Arcand is exploring accessibility. By taking objects in space and assigning different sounds to the different data elements Chandra provides—coding brightness levels or chemical components to different sonic tones, for example—Arcand can create immersive soundscapes that are not visual, but still engage audiences with multi-sensory tools.

“To explore from a research standpoint what can you learn from this data if you're experiencing it in a multimodal way [is interesting],” says Arcand. “But also, just as importantly, if not more so, for the non-expert user, or for someone who's blind or visually impaired, for example, to be able to access that data in a very user-rich way through sound is just really fascinating to me and very satisfying to work on.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sexton_Remy.jpg)