The Invention of Vintage Clothing

It all began with the Davy Crockett coonskin hat craze and a bunch of Bohemians yearning to swathe themselves in decades-old fur

:focal(608x189:609x190)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/28/b72821cc-1ca6-4307-b3a5-8fba12122fce/et201035568web.jpg)

In a culture obsessed with novelty, shopping and fashion, wearing used clothing purchased at thrift stores and flea markets carries a certain anti-capitalist cachet.

In the 1960s and 1970s, groups including the San Francisco Diggers, Vietnam War protesters and radical feminists all advocated the political use of re-use to buck the system. This style of “elective poverty” owes much to the Beat writers of the previous decade, who in turn were inspired by avant-garde artists earlier in the century.

But gather round all you "Fashion Week" followers, for one off-beat tale on the origins of vintage fashion—a story with threads. We weave back and forth through the annals of history, from the 1920s raccoon-coat craze to the 1950s Fess Parker coonskin cap craze (one such novelty is held in collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.) to a party in Greenwich Village and a clientele of bohemians yearning to swathe themselves in dusty, decades-old fur.

Our story starts in 1955 with the soaring popularity of the television hit "Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier." Thousands of enamored boys lusted after the frontier caps worn by actor Fess Parker in the series.

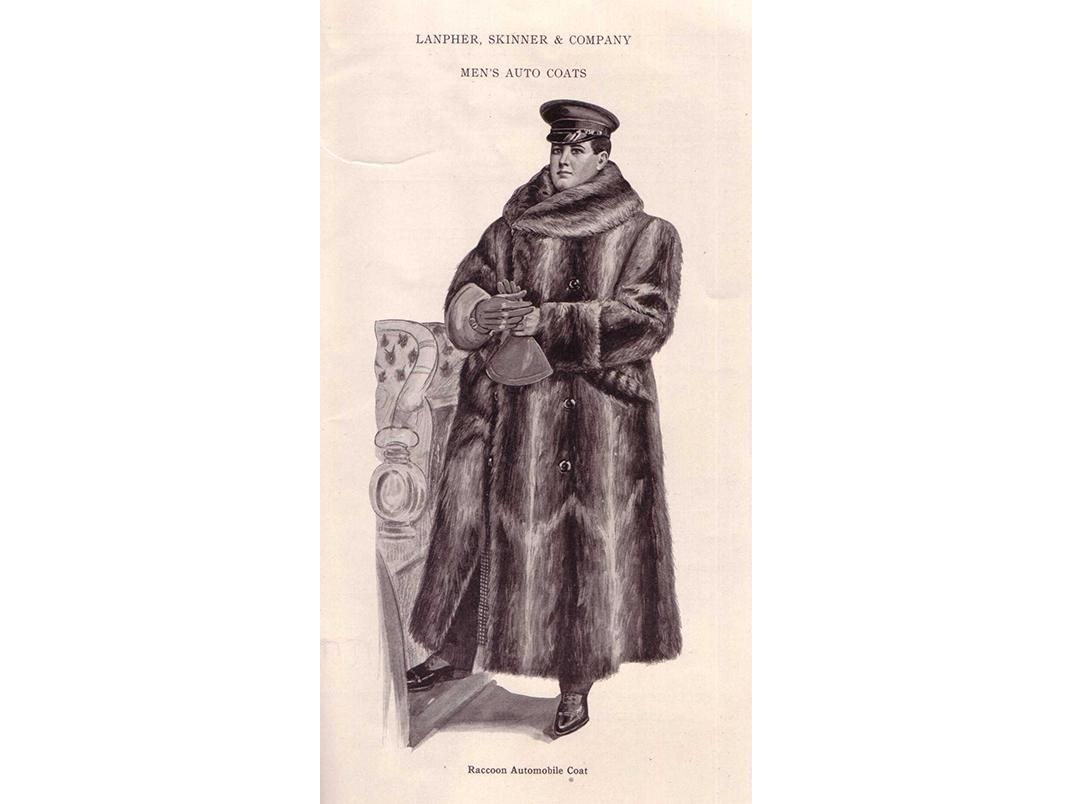

To meet the demand, department stores, in a flurry of fur coat re-use, repurposed the material for hats from unsold raccoon fur coats, adding the coon tails to make the signature frontier accessories. The one in the Smithsonian collections is a classic example. In the wake of "American Century" recognition, the ribbed wild frontier raccoon tail symbolized the popular celebration of rugged American individualism.

According to Smithsonian curator Nancy Davis, in the home and community life division of the American History Museum, it is not known whether this particular cap was cut from an old coat, but the cap, which includes a ringed ‘coontail, is exactly of the sort that could have been sourced from used material.

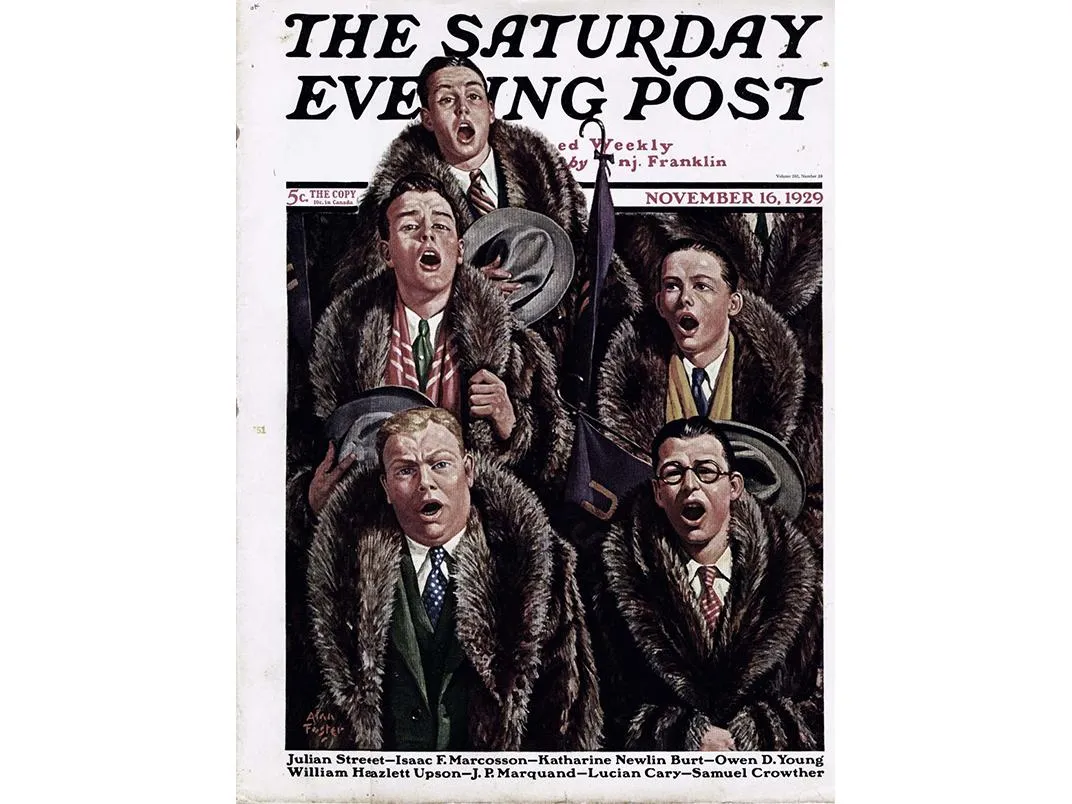

The coats that the department stores were cutting up to make coonskin hats were holdovers from a fad that flourished in the 1920s. Raccoon furs—as the cheapest and most plentiful animal skins—were lush symbols of a new democratic ideal of consumer luxury.

The heavy and unwieldy furs were popular with Ivy League college men, though some spunky girls also sported them, as well as members of the growing, black middle class. "Democratic" though they may have been, the coats were still undeniable emblems of wealth, often retailing at between $350 and $500—about $5,000 adjusted for inflation.

Full-length coonskin automobile coats were the "it" accessory for cruising around a cold New England college town in a Model T—and certainly the most appropriate gear for attending college football games. Football star Red Grange and silent movie heartthrob Rudolph Valentino helped launch the fad, and it spread quickly, peaking in popularity between 1927 and 1929.

But following the stock-market crash, such symbols of wealth, recreation and youthful frivolity quickly lost popularity in the fiscally lean 1930s, and clothing outlets and department stores were left holding the bag.

The supply of the raccoon coats unearthed for the Crockett cap craze became the subject of a conversation at a dinner party one night in the Greenwich Village apartment of the prosperous couple, Stanley and Sue Salzman. The Village was long a bohemian stronghold. But by the late 1950s, as rents rose, starving artists and hipsters had began to drift to the more affordable Lower East Side, leaving the Village to those who could pay—like the Salzmans.

Stanley Salzman, a dapper, successful architect, recounted the dinner party events in an August 1957 New Yorker interview. His wife Sue had been telling guests of how she’d visited a junk shop, spotted a gorgeous raccoon coat, but lost it to a more decisive customer. As it happened, a party attendee, one of Stanley Salzman’s former architecture students, Gene Futterman, volunteered a potential source for another coat and not just one, but also a pile of the old coats—a 20-year-old supply leftover from the original trend of the late 1920s. By one estimate, as many as two million fur coats moldered away in storehouses and were available to any taker.

A relative of his, said Futterman, owned a boys’ clothing store and was using some of that fur coat material to make the Davy Crockett caps, but he had bales of the things stored away, unsure of how to unload the once-expensive supply. In fact, the informant knew about the remaining supply of raccoon coats because he had been offered a summer job chopping them up to make Crockett hats.

Happily for the Salzmans, plenty of intact coats remained. Not only did Sue score her coveted fashion statement, but she also passed one along to each of the 13 guests at the party.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/57/195789fc-a0c8-4954-9b27-234b8defb65f/41_sue_salzman_life.jpg)

Initially, there was no profit motive; Sue was just "on a real '20 kick." But in her blue-black lipstick, floppy cloche hat, and dangling beads, "she was a walking ad," according to her husband. Friends of the fur-clad partygoers and strangers on the street alike queried the lot about their coats. Before long, the Salzmans were in business.

The Salzmans’ coat commerce was an immediate success. By canvassing thrift shops and clothing warehouses, they acquired and sold about 400 of them by late spring of 1957. They suited whole Broadway shows and sold one to actor Farley Granger, a favored lead of Alfred Hitchcock. The Salzmans fueled the furs’ romantic images by reporting that "in one coat, they found a revolver and a mask; in another, a list of speakeasies."

Then in June 1957, Glamour magazine published a photo of one of the coats, naming the Salzmans as suppliers. Phone calls and letters poured in, including an astonishing request from the department store Lord & Taylor.

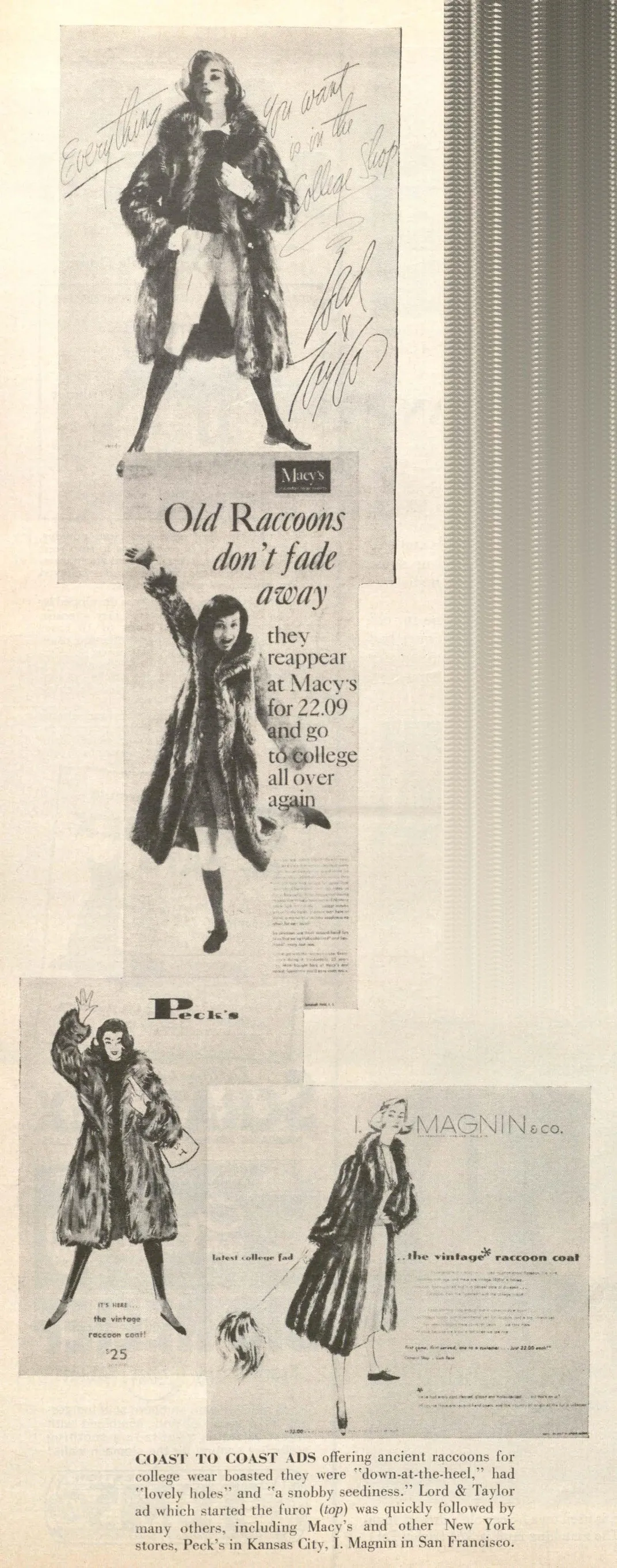

After securing the Salzman’s biggest order yet, Lord & Taylor advertised "vintage raccoon coats" in a promised "state of magnificent disrepair."

College students embraced the vintage coat trend en masse, and as Deirdre Clemente notes in Dress Casual: How College Students Redefined American Style, collegians were fast becoming nationwide trendsetters. Other department stores, including Macy’s, Peck’s in Kansas City, and I. Magnin in San Francisco, quickly exhausted their own leftover supplies and begged the Salzmans to help them keep up. Advertisements promised looks that were "down-at-the-heel," "shabbily genteel," full of "lovely holes," and achieved a "snobby seediness."

Soon though, the moment was over, and not because of the short attention span of young consumers. Thanks to the concurrent Davy Crockett cap craze, the supply of coats simply dwindled away.

Stanley Salzman guessed in 1957 the entrepreneurial couple could have sold 50,000 coats if they had them, but their sources went suddenly dry. Call after call to clothing retailers brought the same answer—most of them had been cut up during the Davy Crockett boom. The waning of "authentic" product led to a quick burst in new raccoon accessories, but the reproductions never had the same cachet.

For the really with it, the only "true raccoons" were the 1920s models; the old coats were part of a popular fascination with the era and appealed to "lovers of the Lost Generation, sports car enthusiasts, lady fashion magazine editors and high fashion models." They fit a gangster’s idea of luxury.

Before the 1950s the word vintage, a word derived from winemaking, had only described coveted older automobiles and fine furniture. In the following decades, exhibitionist vintage dress would merge with elective poverty to create distinctive, backward-glancing hippie styles. To this day, secondhand and vintage clothing attracts a variety of consumers with myriad political, aesthetic and economic motives for their alternative shopping choices.

As hip-hop duo Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’s wildly popular 2013 hit “Thrift Shop” declared, if you’ve only got $20 in your pocket—sporting your granddad’s vintage clothes is an incredibly fine look.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LeZottepicWEB.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LeZottepicWEB.jpg)