In Her Inventive and Prescient Stories, Octavia Butler Wrote Herself Into the Science Fiction Canon

On her beloved typewriters, the literary legend mapped out a course for the future of the genre

:focal(4277x3218:4278x3219)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/5b/c35b9f7e-8fba-4cf7-b411-d05fc9999b96/octavia_butler_typewriter_vertical.jpg)

Octavia E. Butler didn’t like to wait for inspiration. In fact, the celebrated science fiction author denounced the idea of waiting for one’s muse. “Habit is more dependable,” she advised.

The storyteller’s prolificacy is testament to her diligent, lifelong writing habit. Over her 35-year career, Butler used the fantastical narratives of science fiction to explore the complexities and cruelties of survival. Among other things, by placing Black people at the center of her stories, she boldly defied the ways of her beloved but often-conservative genre. “I wrote myself in,” she once said.

Her tales of power-hungry telepaths and erotic alien encounters are now canonical, in science fiction and beyond. The prescience of her “Parable” books, which feature environmental disasters and a leader who wants to “make America great again,” has been especially praised. Even today, says Gerry Canavan, author of a 2016 Butler biography, “It just feels like … she predicts the future.”

Born an only child in Pasadena, California, in 1947, Butler grew up poor, raised by her mother and grandmother. Her father, a shoe shiner, died when she was 3. Her mother, a day laborer who had to leave school at age 10 to work, cleaned houses under the demeaning conditions of the Jim Crow era: Butler sometimes accompanied her mom on the job, where they were required to enter homes through back doors.

Writing became a way of escaping those circumstances. “Their lives seemed so terrible to me at times—so devoid of joy or reward,” Butler said of her mother’s and grandmother’s service jobs. “I needed my fantasies to shield me from their world.” She first put her ideas to paper as a 10-year-old, scrawling stories of magical horses in notebooks and later peck-pecking away on a typewriter she’d begged her mom to purchase. She began submitting stories to science fiction magazines in 1960, amassing rejections until 1970 when she sold her first tale—“Childfinder,” a story about a telepath working to help psychic children.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/25/84254ac0-7d16-4eb4-9802-e4e1e21c27fa/gettyimages-81629740.jpg)

Throughout her years of obscurity, Butler rose daily to write before menial jobs as a potato chip inspector, dishwasher and telemarketer. She also jotted down ideas while crisscrossing Los Angeles on public buses, using the people she observed to plot potential characters and scenarios.

Twelve published novels and two short story collections resulted from this steadfast dedication. Butler found her stride after publishing her debut novel, Patternmaster, in 1976, producing a book a year until 1980. Mainstream success largely eluded her over the following decade, though she won multiple Hugo and Nebula awards, the highest honors in science fiction. While her output began to slow, her reputation grew, and in 1995 she became the first science fiction author to win a prestigious MacArthur grant. Her stories often challenged the basic premises of classic sci-fi, imagining, for example, the ways humans might submit to alien captors rather than resist them. In books such as Dawn and Kindred, Butler showed the ways that gender, race and sexuality inform visions of the future and past. A writing habit that began as a means of escaping her present became a way of revealing its secrets.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a1/c6/a1c68052-6af5-462e-9bae-597f31220f7b/octavia_butler_typwrtr_key_detail.jpg)

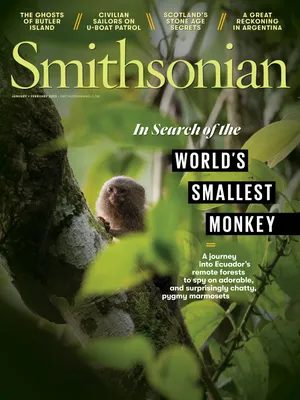

The author did much of this imagineering on typewriters. Her first model was a portable Remington, her second a gift from her early mentor, the larger-than-life science fiction author and editor Harlan Ellison. Several, sadly, were stolen from her home in Los Angeles over the years. She donated one of her well-loved typewriters—this trapezoidal Olivetti Studio 46, painted a cool powder blue—to the Anacostia Community Museum for its 2003-2004 “All the Stories Are True” exhibition, which celebrated Black American literature. By the time she donated this machine, Butler was widely revered as one of the architects of Afrofuturism. Two years after the exhibition, Butler died at the age of 58.

Even in Butler’s most difficult moments, such as the death of her mother in 1996, her habit kept her going. “The major tragedies in life, there’s just no compensation,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 1998 while promoting her novel Parable of the Talents. “The story, you see, will get you through.”