The Invisible Face of the American Worker Is Made Stunningly Visible in This New Show

The National Portrait Gallery kicks off its 50th anniversary with the exhibition “The Sweat of Their Face”

Dorothy Moss, curator of painting and sculpture at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, likes to tell a story about a plumber’s visit to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1897.

“He wasn’t dressed appropriately, he had come into the museum in his overalls on a break from his job on Park Avenue,” Moss says.

He was turned away.

The Met’s director at the time declared, “We do not want, nor will we, permit a person who has been digging in a filthy sewer or working among grease and oil to come in here and by offensive odours emitted from the dirt other apparel, make the surroundings uncomfortable for the others.”

Not only was the museum not welcoming, at the time, the Met was closed on the only day most workers could actually go, Sundays.

One hundred and twenty years later, the Portrait Gallery pays tribute to the oft-overlooked stories of the American worker in the new exhibition "The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers."

“Part of the motivation was to bring the plumber into the Smithsonian,” says Moss. “Steps away from the American Presidents gallery, now we’re seeing the workers, the people who built this country, yet who often remain unnamed and invisible.”

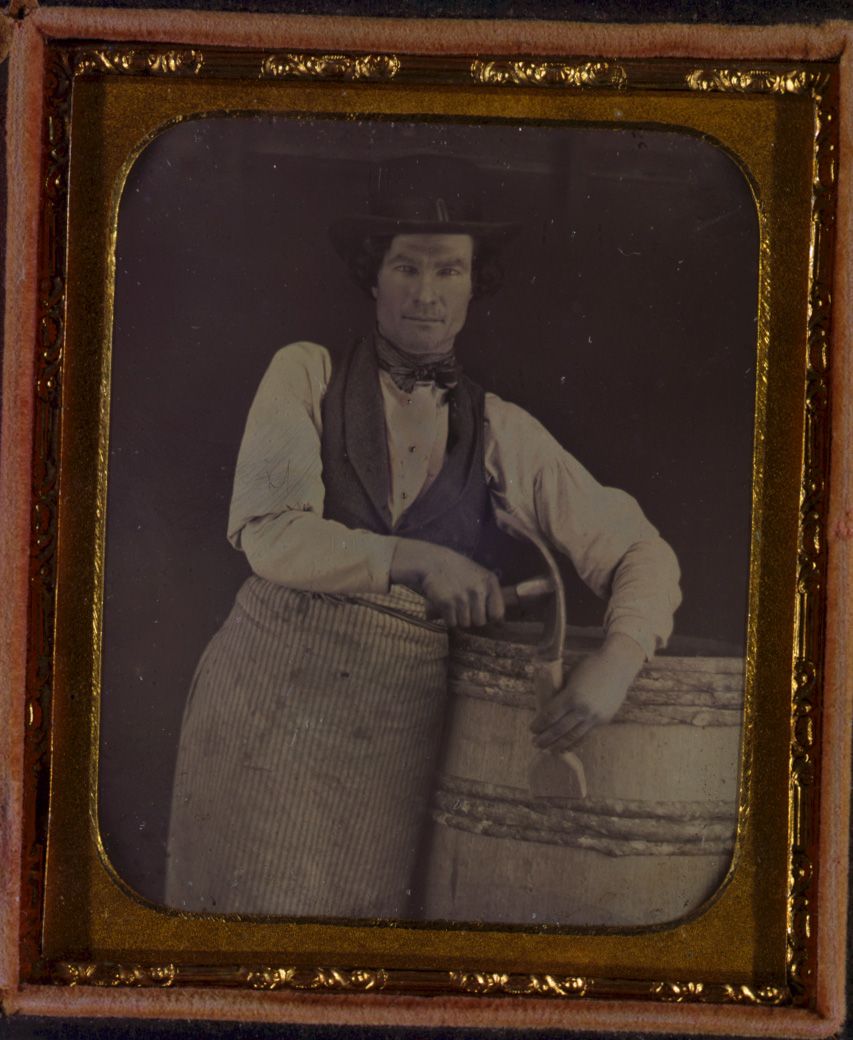

The subjects still largely unnamed in the showing of nearly 100 works of art with photographs, paintings and sculpture by artists ranging from Winslow Homer to Gordon Parks and Dorothea Lange to Danny Lyon.

The exhibition kicks off the museum's 50th-anniversary next year, and comes at a time when the museum's scholars are questioning its role in “some very fundamental ways,” says director Kim Sajet, in terms of “who is included [and] who is not included.”

In fact, only two of the works came from the Portrait Gallery’s collection of more than 23,000 works. The rest were borrowed from other institutions, from the neighboring Smithsonian American Art Museum, to the Museum of Modern Art, Library of Congress, the Phillips Collection, the J. Paul Getty Museum and the place that kicked out the plumber, the Met.

“It’s a major loan exhibition,” says Moss. But that’s all because the stated mission of the Portrait Gallery has been “to acquire portraits of men and women who have made a significant impact on the history and culture of the United States.”

For co-curator David C. Ward, the National Portrait Gallery’s senior historian emeritus, the show capped his own long working career. “I started out as a labor historian in the 1970s and then moved through a variety of iterations,” Ward says. “So to come back to being a labor historian is kind of nice.”

The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers

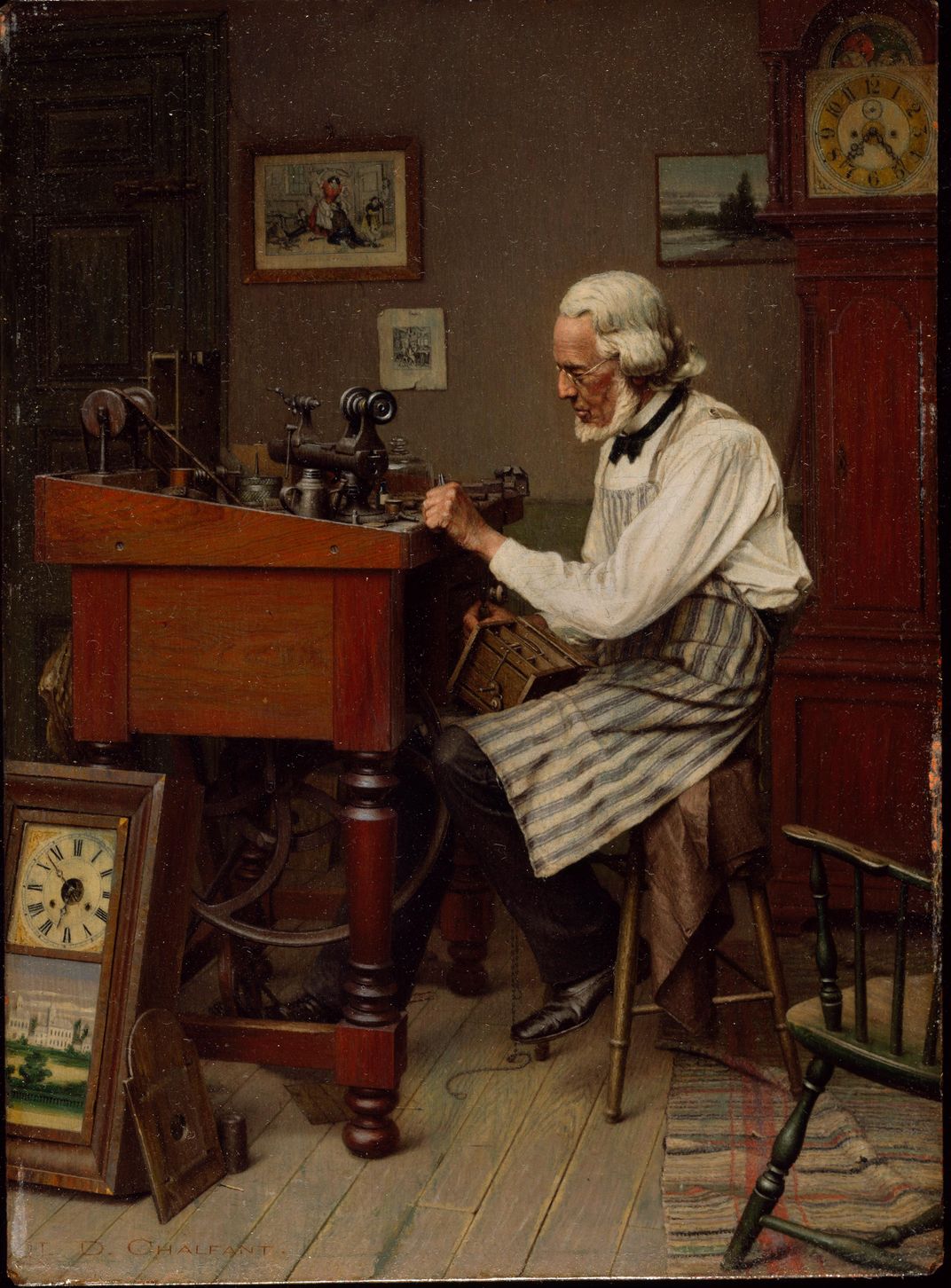

This richly illustrated book charts the rise and fall of labor from the empowered artisan of the eighteenth century through industrialization and the current American business climate, in which industrial jobs have all but disappeared.

Even so, he says, organized labor wasn’t much help.

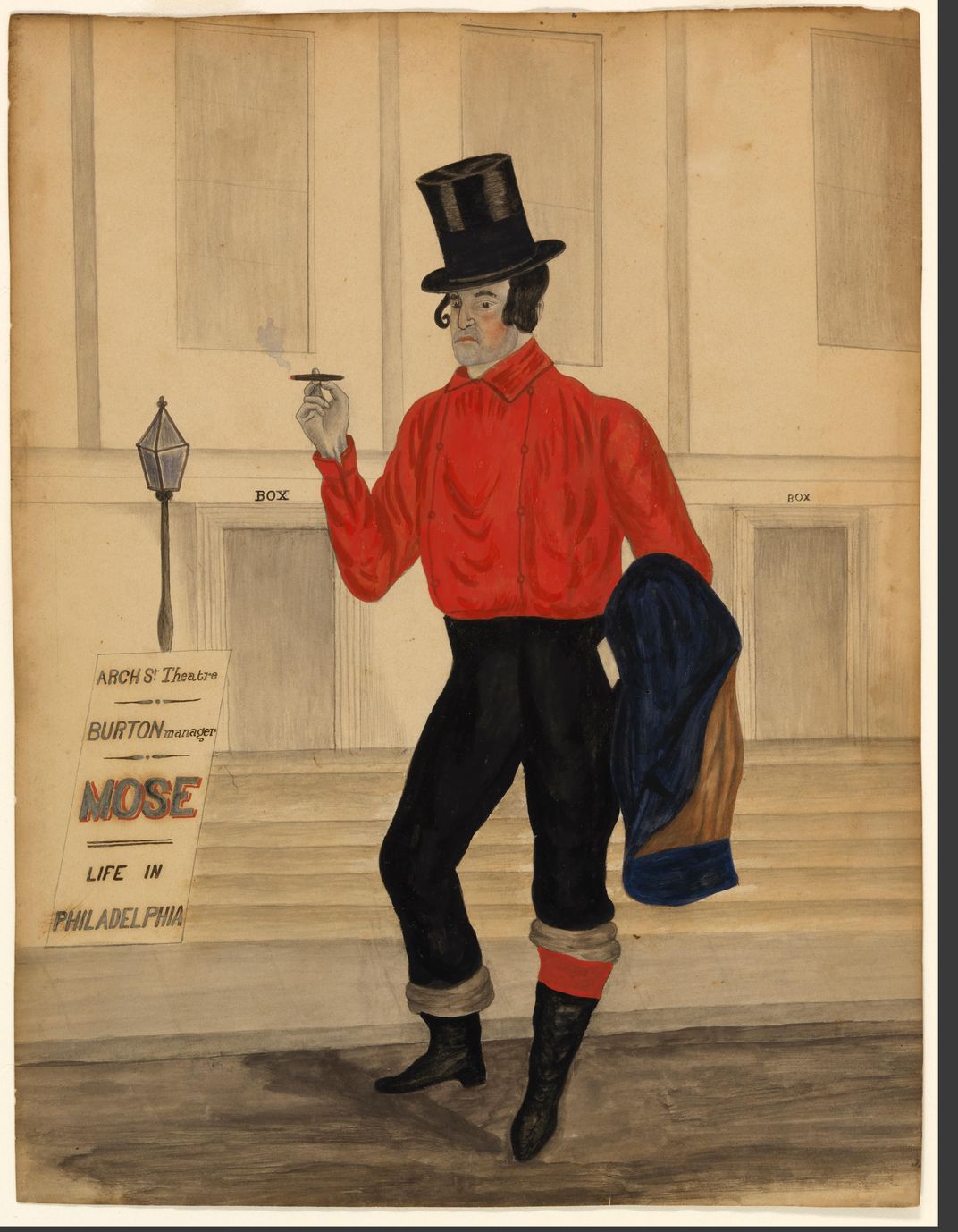

“They said, ‘We got a great picture of John L. Lewis; we’ve got a great picture of Jimmy Hoffa.’ But we were not doing that.” The show, he says, encompasses “uncommon art about the common men and women who made America starting in the late 18th-century.”

That meant a different focus than usual, says Ward, who recalls a friend’s father, a metal worker, asking about past Portrait Gallery exhibits. “He said to me ‘Why are you always doing celebrities? Why don’t you do a show about working people?’”

The Sweat of Their Face does that. And what’s more, Ward says, “The art’s incredible. This exhibition does what the Portrait Gallery does best: it deals with the art of portrayal, but it also deals with the history of Americans.”

It ranges from a rare watercolor on loan from Colonial Williamsburg of an enslaved woman named Miss Breme Jones by South Carolina plantation owner John Rose. “it was discovered only in 2008 in a book and has been recently conserved,” Moss says. “It’s a beautiful rendering.”

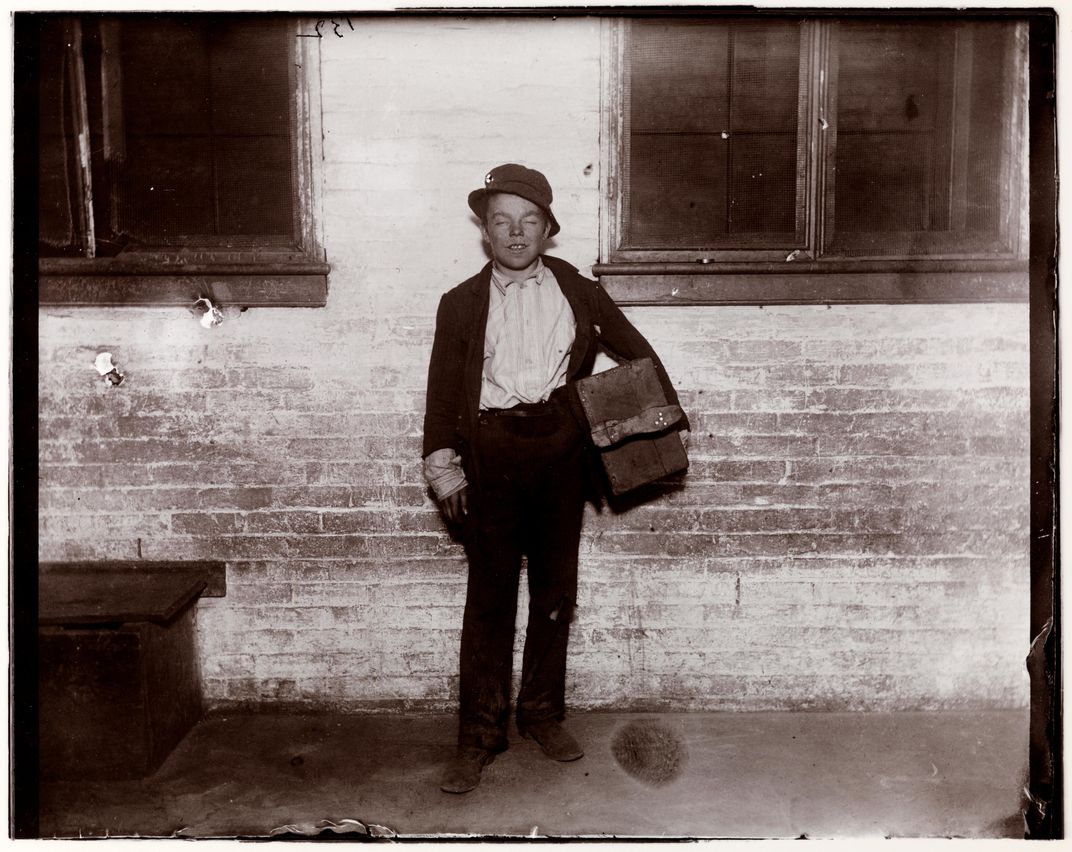

It includes any number of newsboys, sentimentalized for their very anonymity, as well as rustic portraits such as Homer’s Girl with Pitchfork from the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.

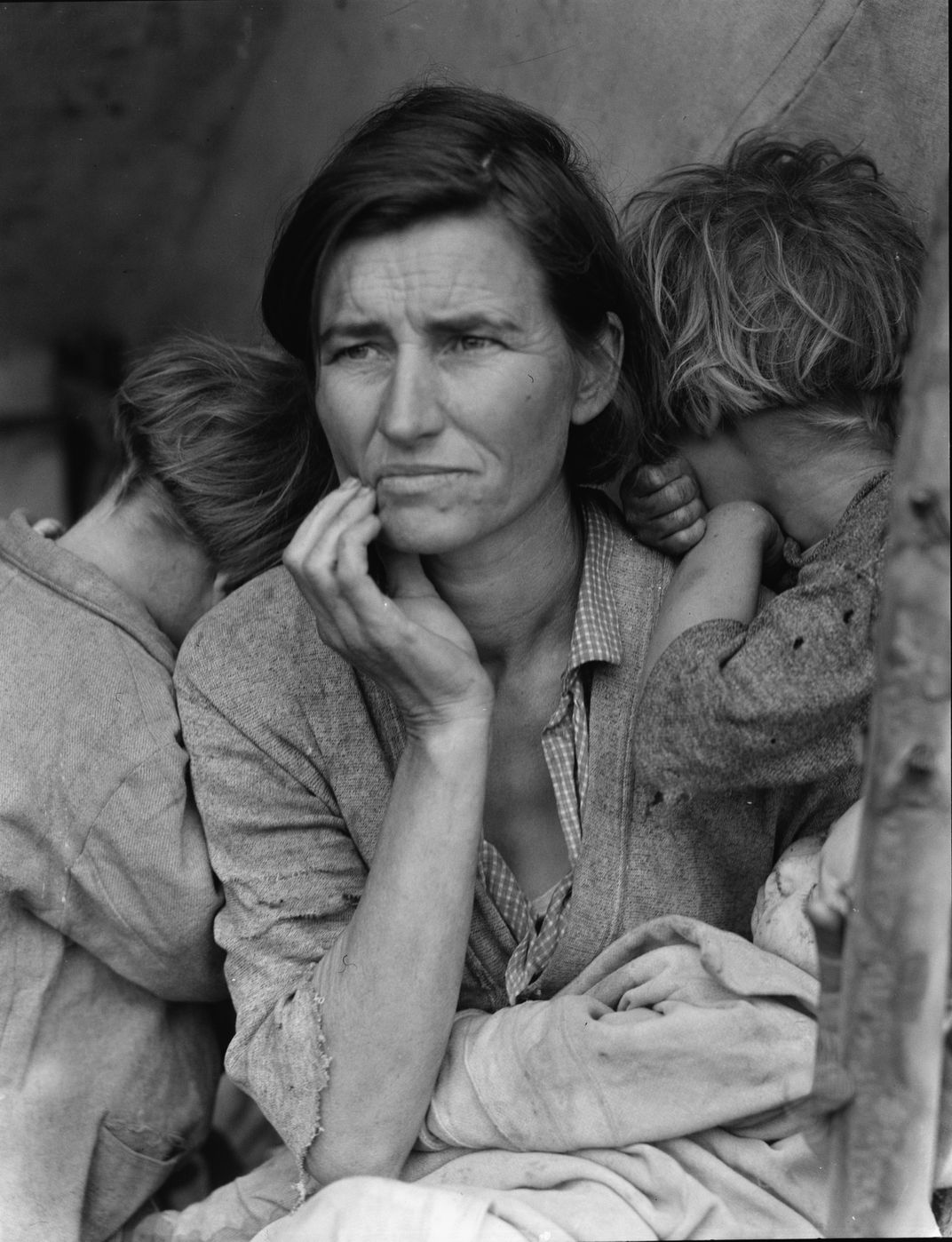

Some of the images are instantly recognizable, from Lange’s Destitute Pea Pickers in California, Mother of Seven Children, Age 32, who famously frets while her children hide their faces, to the (surprisingly small) historical 1869 photograph of the completion of the continental railroad, Joining of the Rails at Promontory Point by Andrew Russell.

The most famous image may be the We Can Do It! portrait of a Rosie the Riveter during World War II.

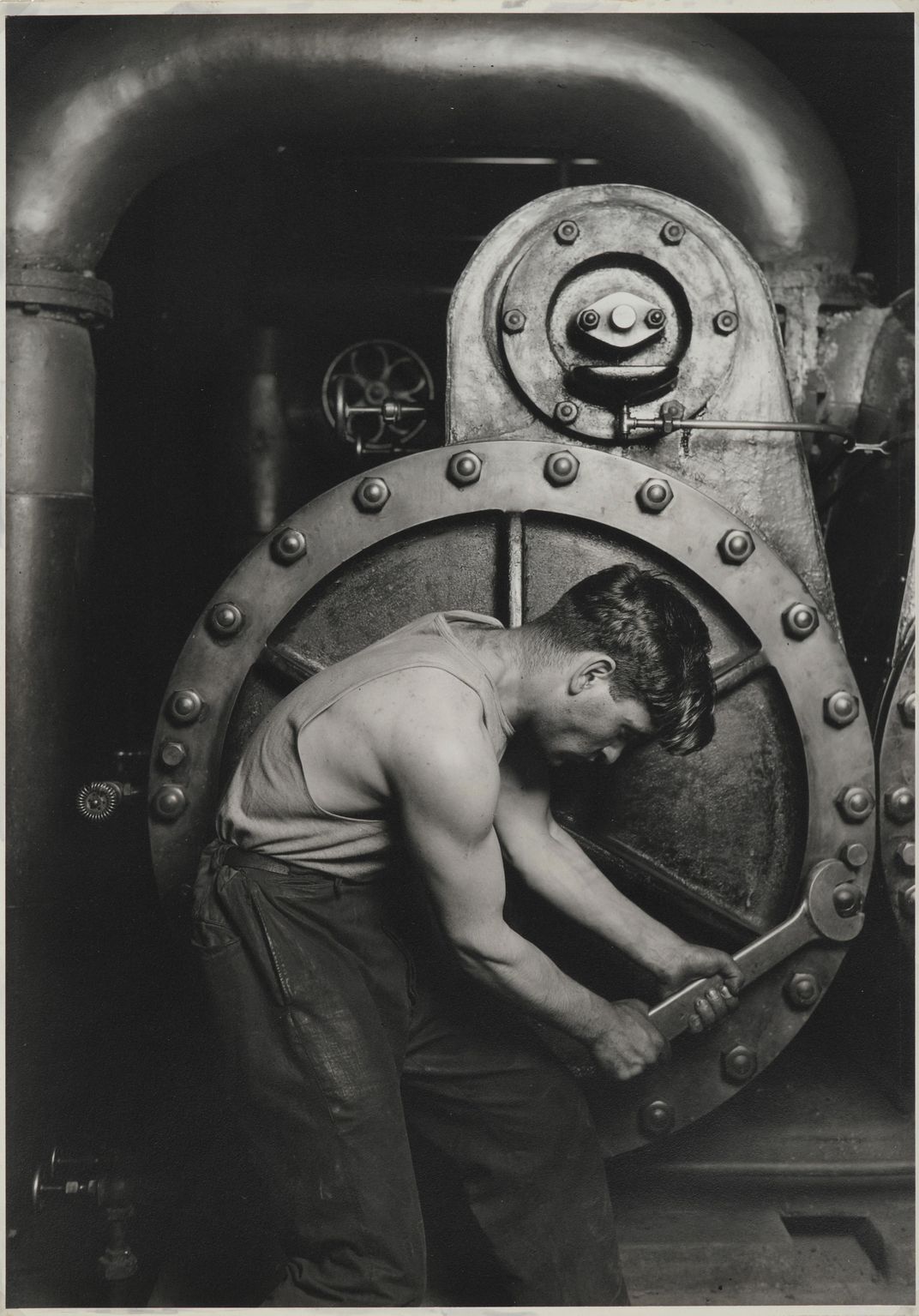

But most others are anonymous, from the Power House Mechanic in Lewis Hine’s 1920 photograph, looking like the wrench-wielding Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. The street urchin Tommy (Holding His Bootblack Kit) in Jacob Riis’ 1890 New York portrait, to the soiled child in Hine’s 1910 photo that got its title later, after the comic book star, Little Orphan Annie in a Pittsburgh Institution.

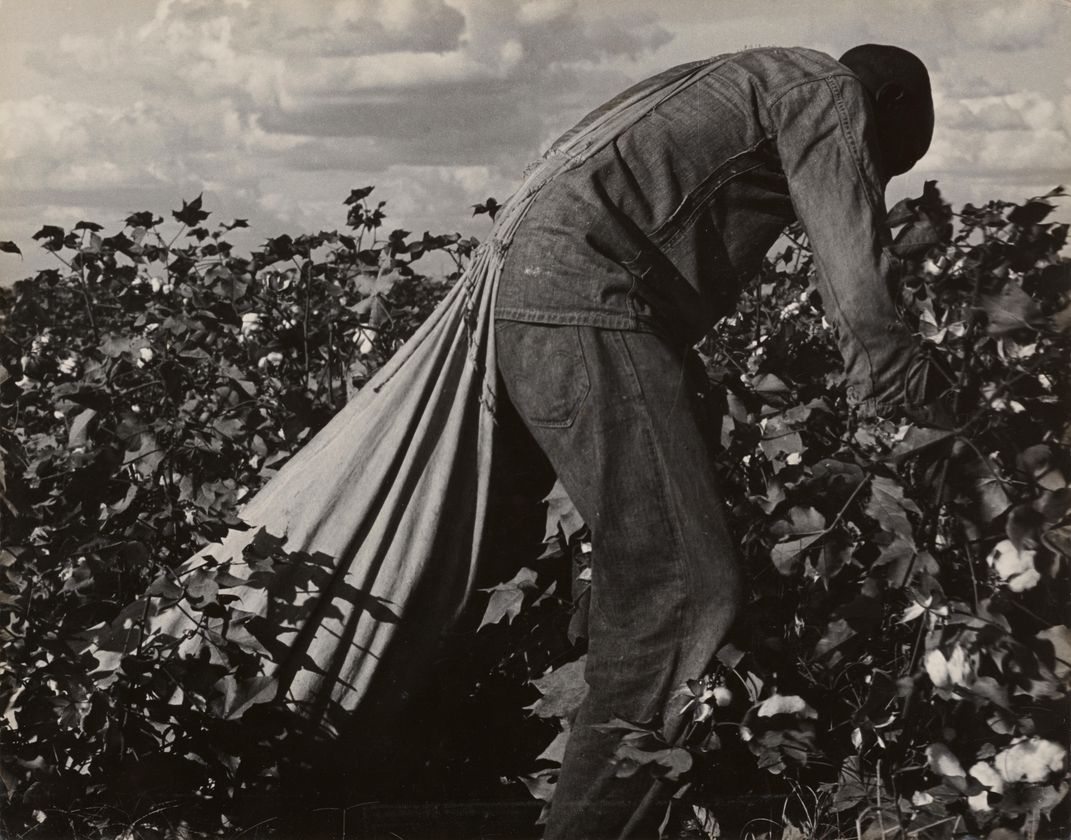

The work moves chronologically and geographically to the West, where the exquisite 1952 Sharecropper linoleum cut by Elizabeth Catlett makes way for Pirkle Jones’ Grape Picker, Berryessa Valley, California, 1956.

The most recent works may hit the hardest, from the disembodied janitor of Josh Kline’s Nine to Five to John Ahearn’s upward looking realistic sculpture of The Gardener (Melissa with Bob Marley Shirt).

Slyest of all may be Ramiro Gomez’ revision of a David Hockney painting of a man showering in a privileged Beverly Hills home, only to show the person who has to clean up afterwards.

Like the rest of the recent pieces, it makes one cognizant of the workers all around us—even the guards of the art museum.

The creators of the work—as well as those depicted—were intended to show a more diverse American than is usually seen at the Portrait Gallery, Moss says. “I had this experience when I started working here five years ago, looking around with my daughter who was five years old, and with her unfiltered eye, said, “This is a boys place—boys, boys, boys.’ ”

While mom was enjoying the great portrait art, Moss says, “She was having the experience of being excluded.”

“I know she’s not alone,” Moss says. “I’ve talked a lot about this with visitors who have come through. I’m hoping this will open up the dialog to include a more nuanced view of history and create more connections for people. I think of this as a start.”

"The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers" continues through September 3, 2018 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)