John Marin, the early American modernist, is best remembered for his paintings of the kinetic desert of Taos Canyon, New Mexico and the razor-sharp dimensions of Red Sun, Brooklyn Bridge. But to Martin Kotler, a frames conservator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), the frames encasing Marin’s work are just as important as the canvases inside.

Over the course of his career, Marin sought a “Blessed Equilibrium” between every painting and its frame. He worked with New York City frame maker George Of to create custom mounts, which he coated in watercolors to enhance the palette of the painting inside. Later in his career, Marin made his frames by hand, and steadily pushed his art over the edge: The black frame of Sailboat, Brooklyn Bridge, New York Skyline is streaked with silver, like the lines on a well-trafficked road.

But past private buyers and museum conservators have rarely treasured frames like Kotler does. Some frames were cataloged and stored, some were forgotten and rediscovered, and others were discarded outright. Until recently, most people—experts included—saw picture frames as interchangeable and expendable, if they ever thought of them at all.

“When you are in school, it’s never discussed,” Kotler says of frames. The names of many frame makers are lost or forgotten. On test slides and in textbooks, works of art are almost exclusively depicted unframed. The academic blind spot is passed on to visitors. “When you have people walking into a museum, there are so many things to discuss,” Kotler says. After composition, colors, and the artist’s biography, there’s hardly time to discuss the molding.

That’s partly by design: frames are fundamentally utilitarian objects. They exist to protect art from rough handling, the proximity of people and environmental factors like dust and light. They also offer a guardrail for the viewer’s wandering eye. “It [is] the mother holding its child,” Kotler says. But many frames are works of art in their own right—and deserve to be seen as such.

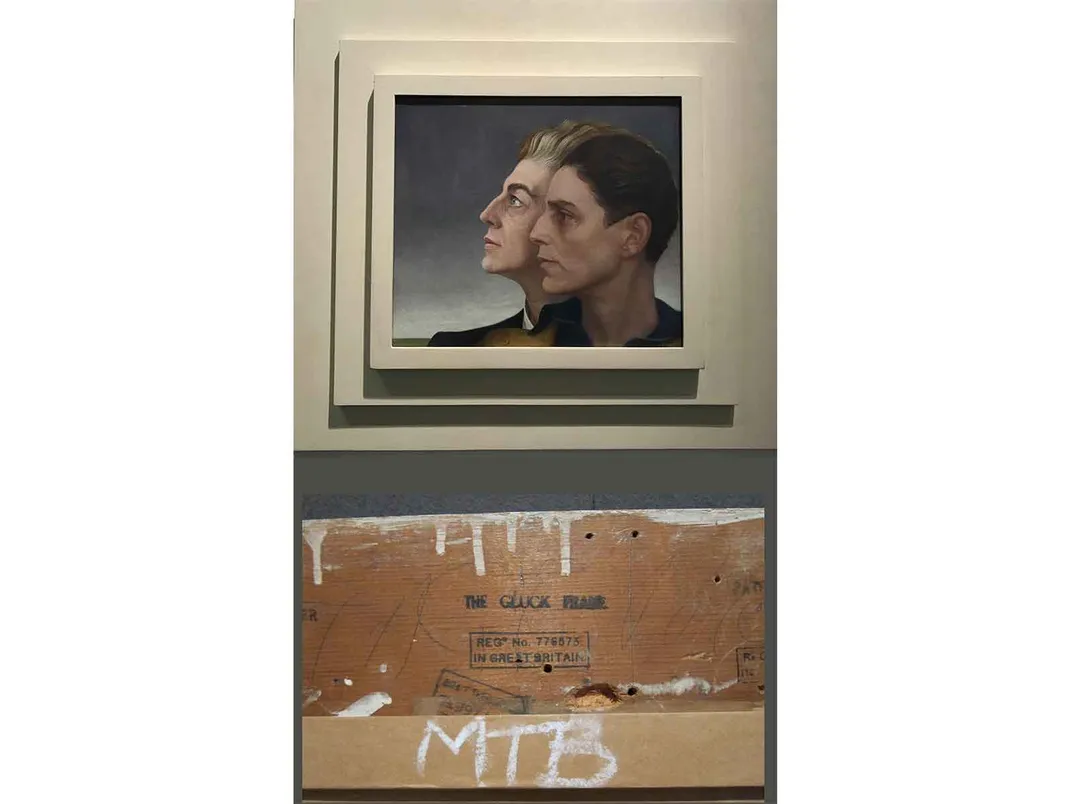

Some objects, like those of Marin or contemporary artist Matthew Barney, a pioneer in plastics, are “artist frames”—made by the artist and therefore inseparable from the artwork. Others are commissions fulfilled by master frame makers, like bold Beaux Arts architect Stanford White (he sent his fantastical designs to artisans for execution), the luxury Boston shop Carrig-Rohane (which Kotler calls the “Rolls Royce of framing”), or the carving virtuoso Gregory Kirchner (who made just 12 known frames). And still others are made by conservators like Kotler, who builds subtle, secure and historically accurate cases for SAAM’s treasures.

“Frames have suffered exile and destruction,” says Lynn Roberts, a freelance art historian and founder of The Frame Blog. But we can learn to see again. When people “realize that there’s another history there, they start asking more and more questions,” Roberts says. “They’re fascinated by how frames are made, and what they do, and their sheer variety and beauty.”

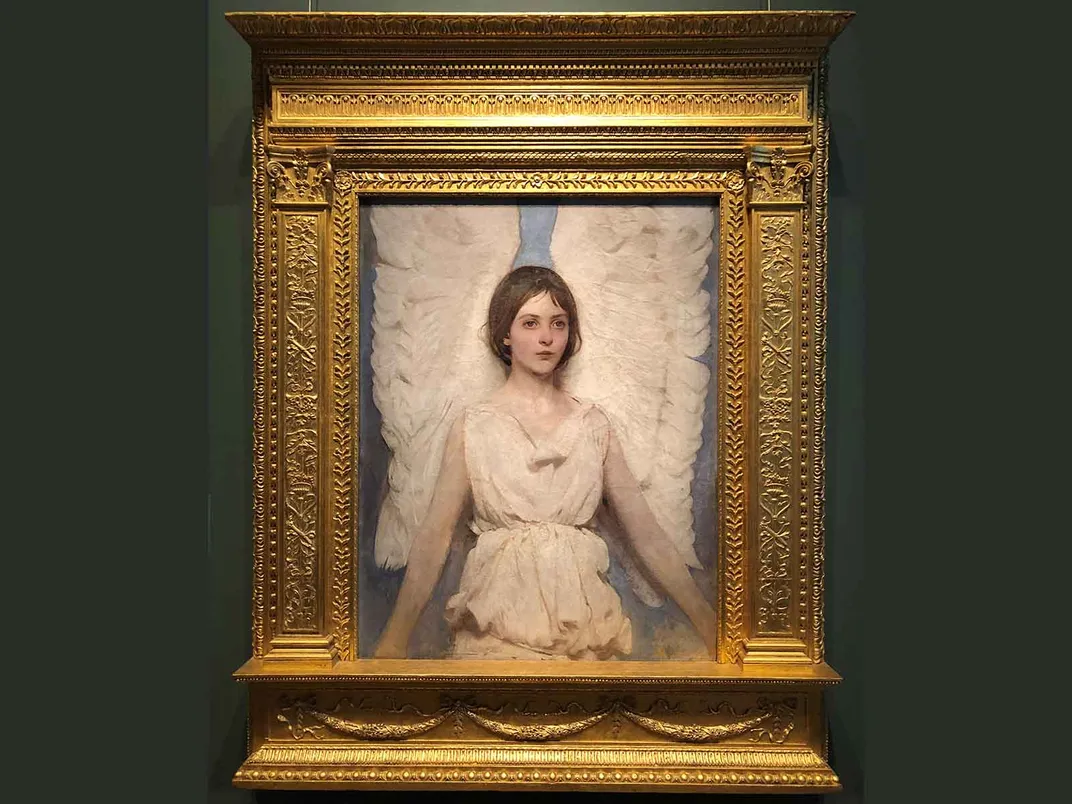

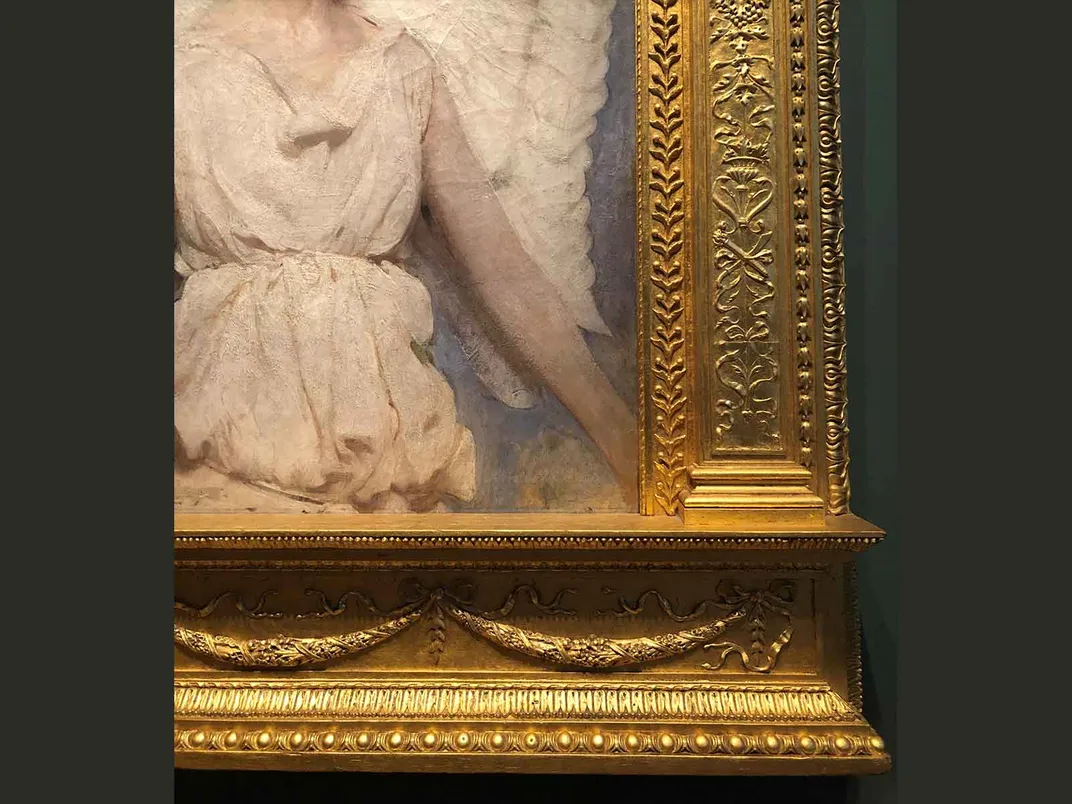

Frames have always been a form of protection. But that narrow view was “very rapidly subsumed by the realization that now there was another empty field between the painting and the wall, which could itself be used and decorated,” says Roberts. While four pieces of wood would suffice for security, frame makers delighted in the gilded and polychrome curves of Baroque frames, the asymmetrical Rococo peak and the stepped geometry of Art Deco casing.

While European shops were iterating on their designs, most Americans were content with mass-produced “frames of convenience,” Kotler says. Before 1860, they imported these ornate slabs and slapped them on paintings across the country. It didn't matter if it looked good, it just had to fit. While domestic shops eventually emerged in Boston, Philadelphia and New York, their works weren’t necessarily original. Manufacturers were often prolific thieves. If someone like White revealed a revolutionary new frame, shops across the country quickly developed imitations—a perfectly legal proposition, even today few patents protect frames and framing.

But as the 20th century approached, Gilded Age artists began to think more critically about the entire process. Members of the Ashcan School, for example, wanted frames that reflected the raw, unsentimental spirit of their work, not that of an Old-World cathedral. By the advent of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, many artists decided they didn’t want frames at all.

“Modern painters felt that if you put on a historic frame style, it would take away from the aesthetics of the painting,” says Dale Kronkright, head of conservation at the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. O’Keeffe and her contemporaries wanted viewers to consider the way the shapes, colors, line and composition worked, without distractions. To ensure her vision was realized, O’Keeffe worked with Of, the New York City frame maker, to develop eight distinct frames that precisely suited her paintings.

While stewards of O’Keeffe's work have carefully preserved her frames, other artists haven’t been so lucky. “Good taste”—at least as it's conceived in the moment—has often overruled historical truths. Steve Wilcox, a former frames conservator at the National Gallery of Art, says museums used to remove original frames in favor of a house style. “Nobody was taking it seriously as an ethical process,” says Wilcox, who is known around the district as the “Mick Jagger of frames.”

Private collectors were often even more egregious. Roberts recalls that a Degas recently appeared on the art market with its original frame intact, but the auction house replaced it with a giltwood frame. “It looked meretricious and chocolate-boxy, and Degas would have been horrified,” Roberts said. But “for the commercial world a carved giltwood frame makes something appear a million dollars more important.”

Today, most museums seek to display their collections in frames that are true to the period in which the work was created and the vision of the artist. But the centuries-long devaluation of frames can make this humble goal a Sisyphean task.

“You could be looking through volumes and volumes to find that one sentence,” Wilcox says.

The first aim is to determine an existing frame's relationship to the work inside. The job requires a wide and deep knowledge of historic frame styles and materials and, often, an extra set of eyes from curators with domain expertise, says Janice Collins, a framing specialist at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Curators wanted to update the frames on the work of Josef Albers, a modern artist best known for his series Homage to the Square. But Collins spoke with an expert on Albers, who explained that the artist carefully selected his own frames. So the original fixtures stayed.

If the frame is original, many conservators will try to investigate its origin story. Since the 1990s, Kotler has spent his spare time hunting down a man named Maurice Fincken, who made a frame for a painting by John Sloan. “There’s this beautiful paper label on the back, but you go and do a search, and there’s zero,” Kotler says. “Now my curiosity’s up.” With some more digging, he found that Fincken was working outside of Philadelphia, but largely disappeared from the records around the First World War. More recently, Kotler identified a descendant who may be able to explain more of the story.

“It’s like detective work,” he says.

Once its provenance is established, conservators work on preserving the frame, which has likely experienced wear, tear and less-than-artful touch-ups. Kotler recalls his work on Alexandre Hogue’s Dust Bowl and artist frame. “A million years ago, the museum said, ‘take that frame off and design and make another frame that was more sympathetic,’ because it’s really an ugly frame,” he says. Kotler did as he was asked, but he kept the original frame, and “slowly, slowly cleaned off the stuff that other people did.” When a museum in Texas did a retrospective of Hogue’s career, Kotler was able to ship it to them with its original frame. It wasn't beautiful, but it was true to the artist.

If an artwork is in an inauthentic frame, it’s a frames conservator’s job to find a suitable, empty alternative, or build one from scratch. At Smith College Museum of Art, for example, the Ashcan artist George Bellows’ painting Pennsylvania Excavation had long been displayed in a Louis XIV-style frame, all braided and gold. But students in the college’s frame conservation program built an alternative—still gilded, but with a subtle reeded molding more suited to Bellows’ work.

Despite centuries of neglect, the frame may finally be coming into its own. “It’s a fairly new field, in terms of art history, but it’s made leaps and bounds in the last 15 years,” Wilcox says.

Where Wilcox remembers just one book on framing when he started out in the 1970s, today there are dozens, and sites like The Frame Blog make conservators’ insight available to the masses. The marriage of time-honored craftsmanship and new technology has led to the development of environment-controlled frames that still honor the intent of the artist. And some museums, mainly in Europe, have curated exhibitions dedicated to the art of framing, including the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Louvre.

While he recently retired to the mountains of North Carolina, Wilcox says he hopes to lead workshops for frame “geeks” around the world, and continue to nurture our nascent respect for framing. But for now, he says, “I’m just enjoying my view.”

A view framed by the window? “I hadn’t thought of it that way,” he says with a laugh.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/42/4e42525b-d5b6-4ff6-8bdf-5c9d59fba624/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/77/9a77d6e0-11a8-440e-80bc-93307d241e5b/longform_desktop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/grad.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/grad.JPG)