The World Is Finally Ready to Understand Romaine Brooks

An early 20th-century artist, Brooks was long marginalized, her work overlooked, in part because of her fluid sexual and gender identity

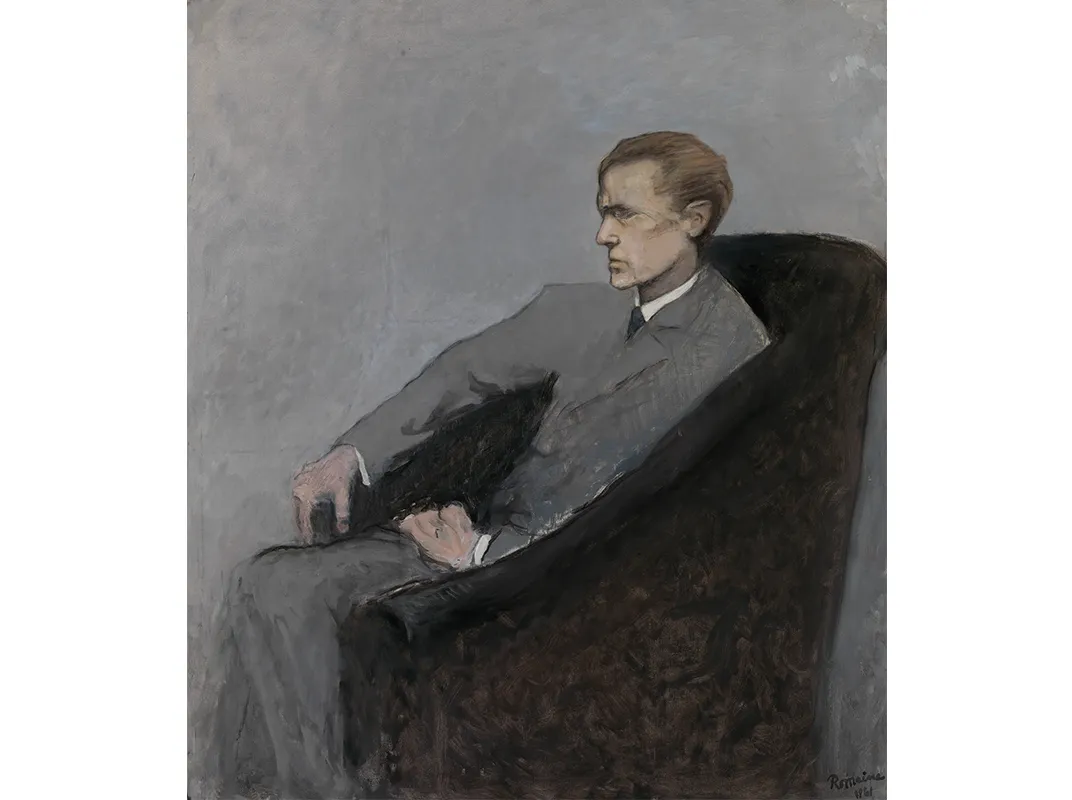

The striking, nearly monochromatic works of Romaine Brooks are receiving a fourth major showing at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., which owns about half the known output of the American expatriate who lived in Paris.

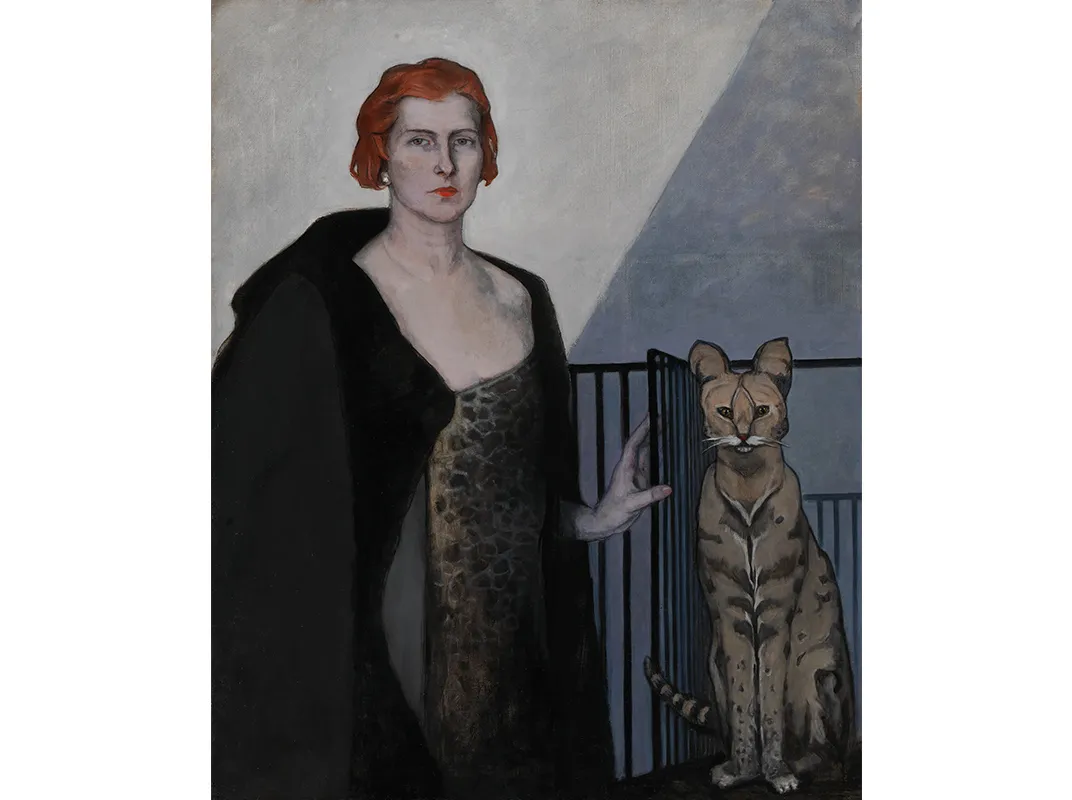

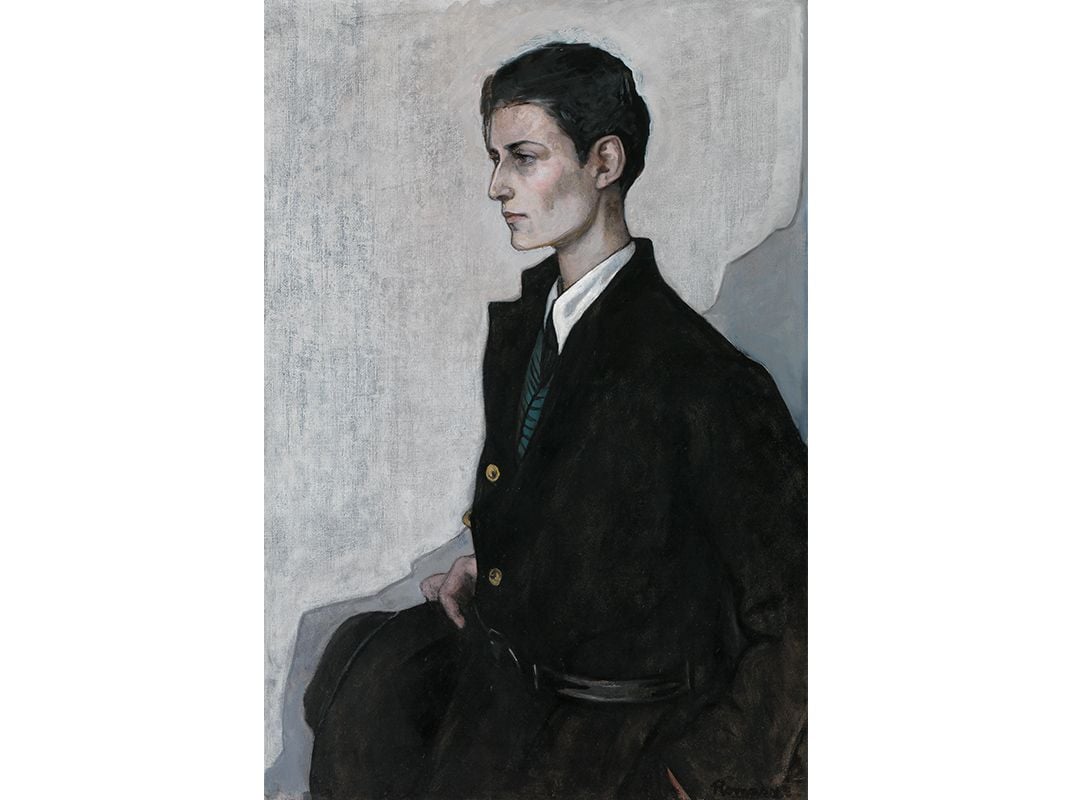

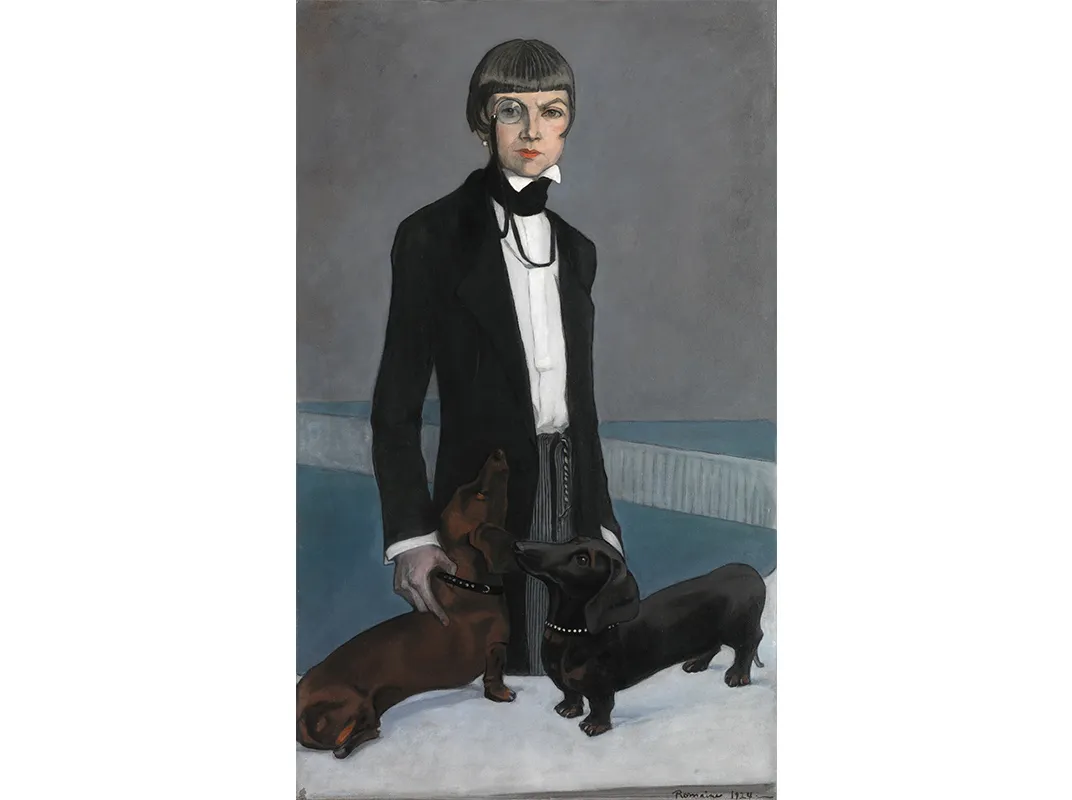

But the new exhibition, “The Art of Romaine Brooks” on view this summer, speaks most frankly about her sexual identity—her work is almost exclusively about women, and her own self-portraits show her in men’s clothing and a top hat.

The exhibition includes the 18 paintings and 32 drawings in the museum's collections—works we’ve seen before—but Joe Lucchesi, the contributing curator, says “the thing that is profoundly different about this show is the framing around the artist’s life itself and the issues of gender and sexuality that are really at the core at the work.”

The last Smithsonian showing of Brooks, in 1986, came at a time when feminist scholarship was just beginning, says Lucchesi, an associate professor of art history and the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies program coordinator at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

“There’s a profound cultural change that’s happened between the 1980s and now,” he says. “It’s actually quite interesting to me to think about that show and the one that’s up now as being on opposite sides of a huge culture shift that’s occurred over the last 30 years.”

It results in a higher profile for an artist who should be recognized as a leading cultural figure of the 20th century, according to biographer Cassandra Langer, author of Romaine Brooks, A Life, who recently spoke at a Smithsonian symposium on Brooks. “She stands alongside Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein as a major participant in the intellectual and artistic life of her times and beyond,” Langer says.

The American artist was born in Rome in 1874 as Beatrice Romaine Goddard, heiress of a mining fortune after following a troubled childhood where her father left the family, her mother became emotionally abusive and her brother was mentally ill.

"Brooks had a Gothic childhood replete with a mad cousin in the attic, an abusive and cruel mother, a conservative and cold sister and an insane brother,” Langer says. “As a child she was beaten and humiliated.”

Even living in a mansion, she often had to fend for herself. “It’s a little Tale of Two Cities,” Lucchesi says. “She’s a super rich girl, living like a street urchin. And nobody believes she’s a rich girl.”

She became a poor art student in Italy and France before she inherited the windfall that allowed her independence and a new way of depicting her world.

“She was one of the first modern artists to depict women’s resistance to patriarchal representations of the female in art,” Langer says. “She understood that women in art had been treated as objects rather than subjects. She made it her mission to change all that.”

That put her ahead of her time.

“Sexuality, gender and identity are now at the cutting edges of the current arts scene,” Langer says. Brooks (who got that name from a marriage that lasted less than a year) “started this conversation long before it became fashionable to do so.”

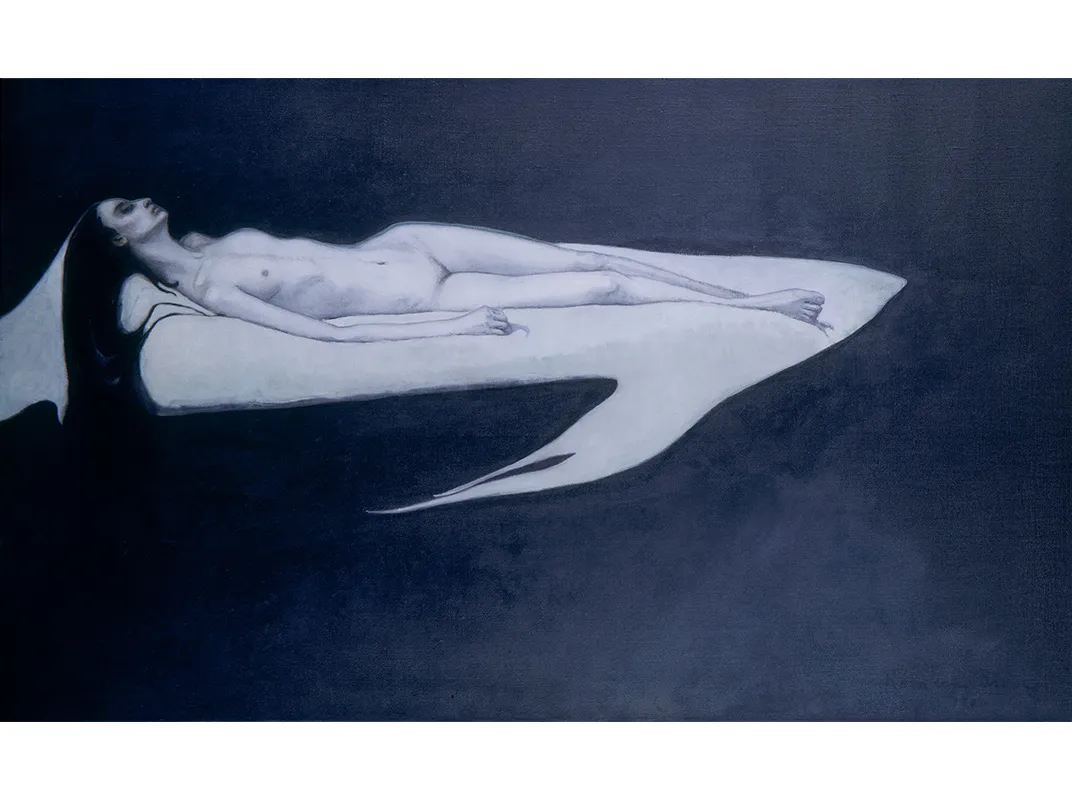

Her early nude, Azalées Blanches from 1910, was an unusual subject for a woman. “I grasped every occasion no matter how small, to assert my independence of views,” Brooks said in her unpublished memoir. Its provocative pose led to comparisons to the figure in Édouard Manet’s Olympia.

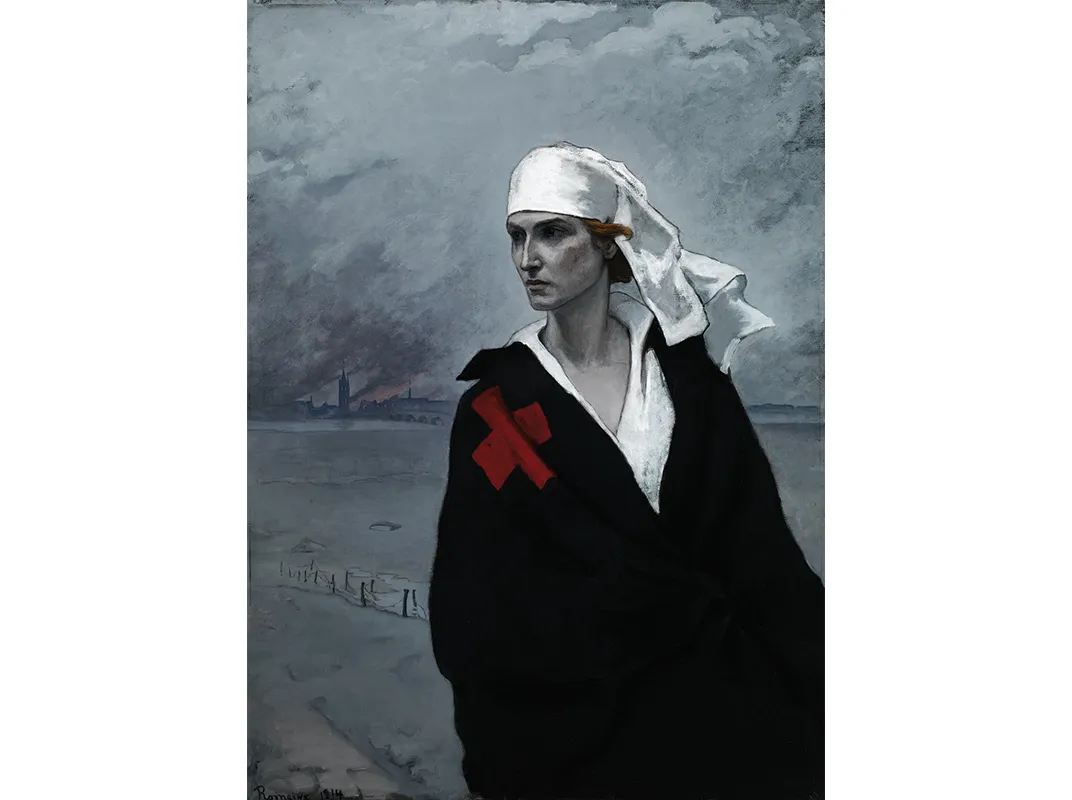

Brooks turned to performance artist Ida Rubinstein, whom Langer calls “the Lady Gaga of her day,” as a model for one of her best known paintings, that of a Red Cross relief worker outside a burning French city in the 1914 La France Croisee.

That Brooks was in love with Rubinstein was not as well known but certainly not hidden.

“Some of the critics at the time danced around some of the sexual identity issues, but they always understood it as a little bit of boundary pushing, and almost always characterized it as something very inventive, very forward thinking,” Lucchesi says.

Reproductions of the image exhibited at the Bernheim Gallery in Paris in 1915 raised money for the Red Cross, and as a result Brooks won a Cross of the Legion of Honor from the French government in 1920.

Brooks was proud enough of the medal to include it, as one of the few spots of color in her celebrated, typically gray 1923 Self Portrait, in which she devised a proudly androgynous mask for herself as carefully as did an artist much later in the century, Langer says. “Like David Bowie, she became very good at projecting her confected self. But this was just a cover for the very vulnerable and needy child she still remained.”

Because of her sexuality, Brooks “has been marginalized,” according to Langer, “most significantly due to the homophobic misunderstandings of her domesticity.”

But her chosen artistic style was also at odds with the increasingly fashionable cubist abstractions of the era. At the time when Stein’s nearby salon was celebrating the work of Picasso, Brooks’ moodier representational works were more comparable to that of Whistler.

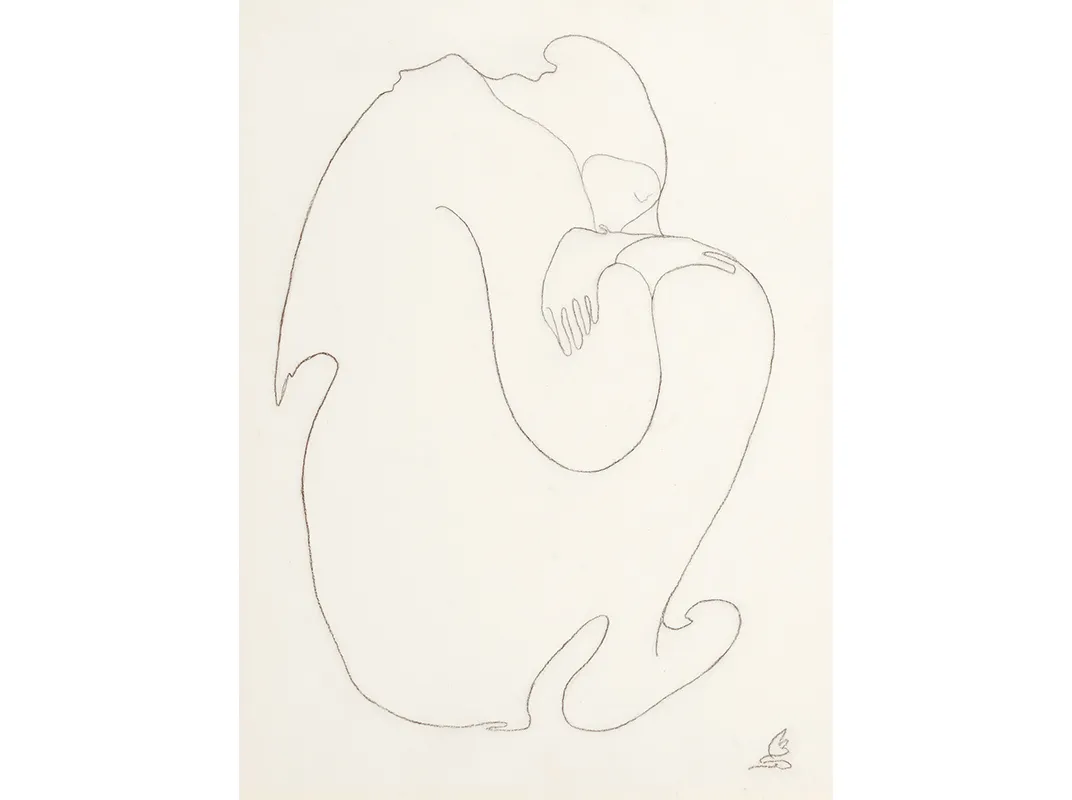

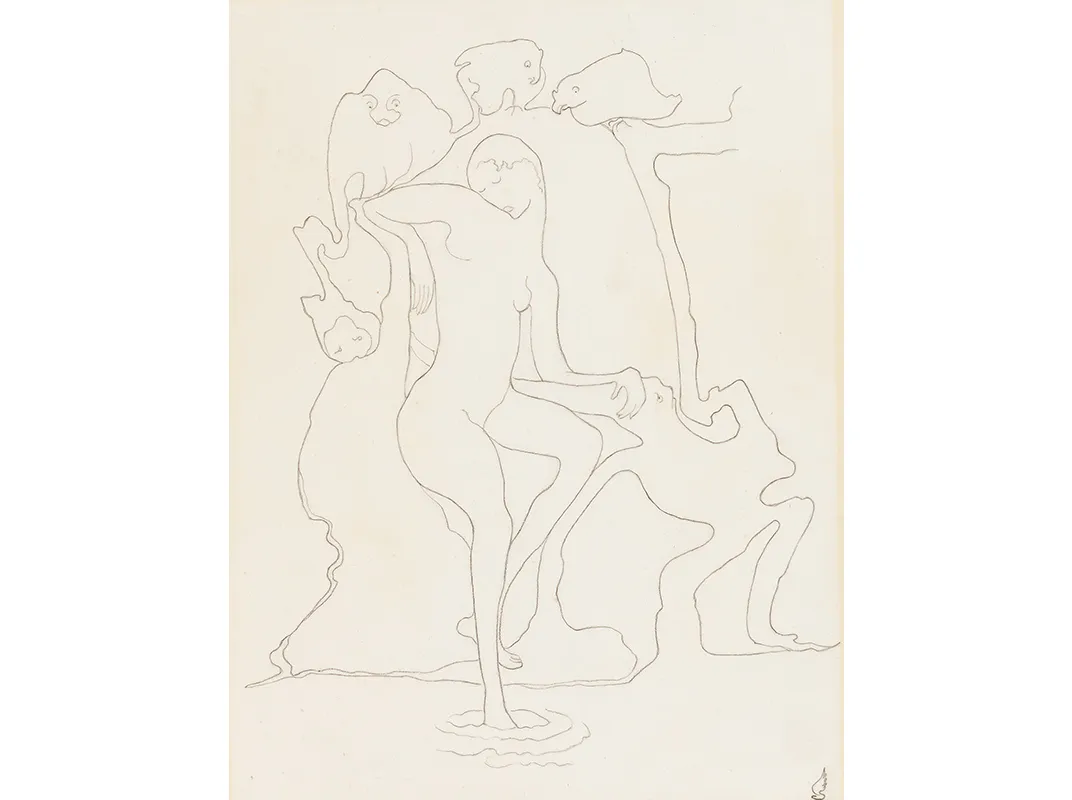

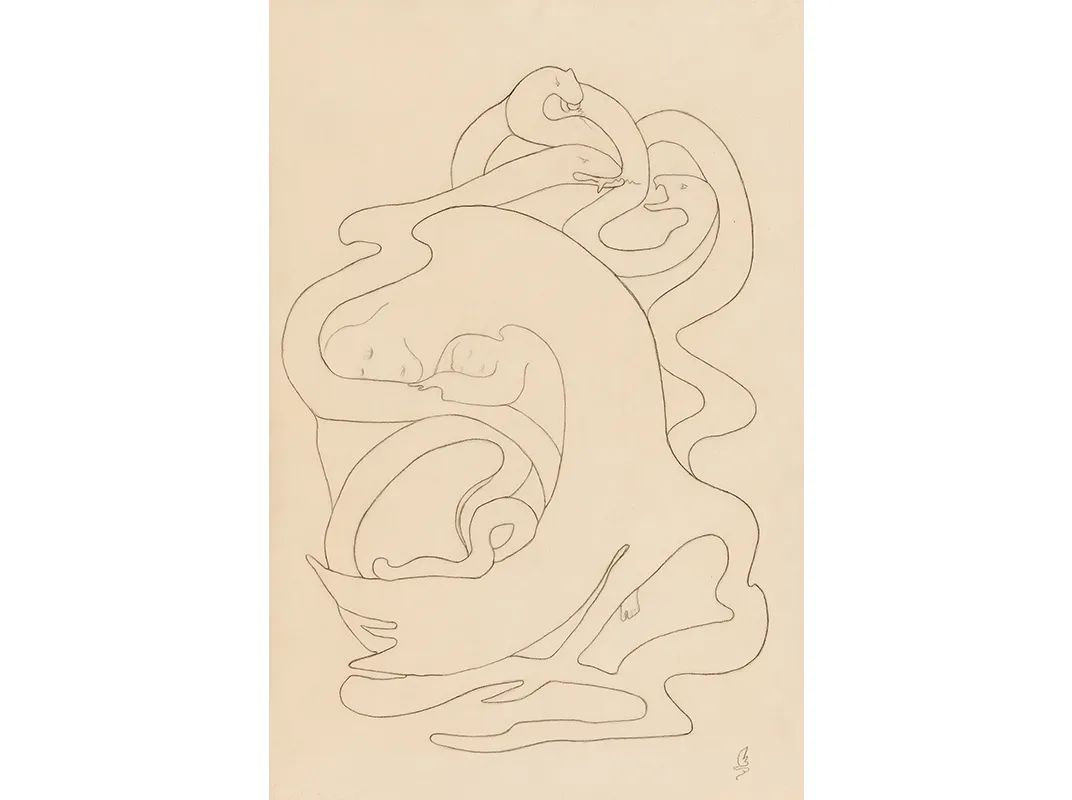

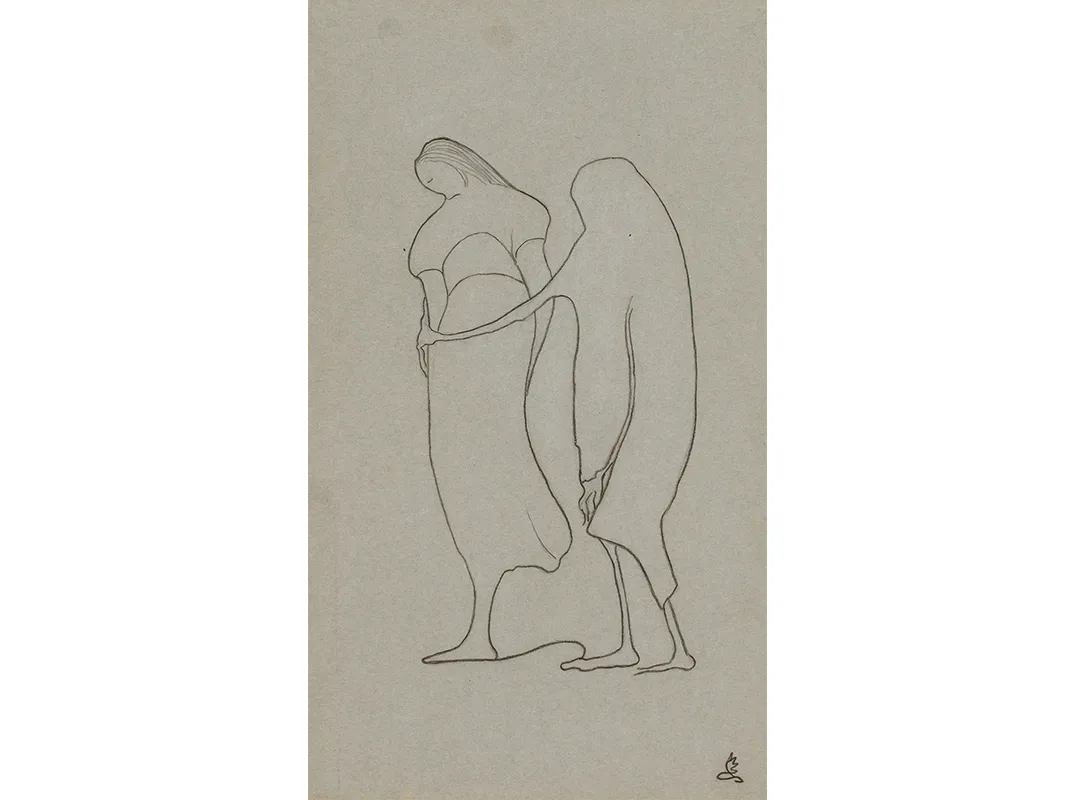

Brooks retreated from paintings for decades, concentrating on fascinating, psychological drawings that Lucchesi says are of equal interest (and also on display).

She stayed true to her vision throughout, although by the time she died in Paris in 1970 at the age of 96, she had been largely forgotten. (Her own defiant epitaph was: “Here remains Romaine, who Romaine remains.”)

“It’s very difficult for female artists historically to garner a lot of attention, and then you add the sexual identity issues—I think all of those things kept her out of the mainstream,” Lucchesi says.

For her part, Langer says, “I always considered her queerness paradoxically essential and beside the point. The simple truth is she was a great artist whose work has been misinterpreted and overlooked.”

More and more people are aware of Brooks, thanks in part to a 2000 show at the National Museum of Women in Art, a few blocks away from the American Art Museum, also curated by Lucchesi.

But in the last big Smithsonian show in 1986, her sexual identity issues were “pretty coded,” he says. The American expatriate writer “Natalie Barney barely shows up in that catalog even though they were basically together for 50 years,” he says.

It wasn’t the Institution that was conservative, “it’s kind of the way the world was.”

But to take in the work now, he says, “what you’re seeing is an LGBT subculture in the active process of trying to define itself,” Lucchesi says. “And that’s really exciting to me.”

In her paintings, he says, “she’s participating in an effort to shape a visible image of what it means to be a lesbian in that era. And I think that’s very significant."

In 2016, “I think there’s a lot of interest in her work because there’s a bit of a recognition with things that are going on now with, for example, trans identities or more gender-fluid identities, and it’s very interesting to look back at someone 100 years ago who was also navigating things that weren’t so clear and developing a language really for the first time.”

That the show of 18 paintings and 32 drawings opened days after a LGBT-targeted massacre in Orlando makes the exhibition bittersweet. And yet its portraits in grays and black reflect a somber mood of the community after that tragedy.

“There’s a kind of quietness about her work, there’s a kind of heaviness to it, a seriousness to it that I think suddenly was very apparent in that moment of mourning,” Lucchesi says. “I hate that it became interesting for that reason. But there is real opportunity to have the show participate in some of the conversations that are happening right now.”

“The Art of Romaine Brooks” continues through October 2, 2016, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/d3/e4d3a400-c720-4308-b889-2aa3463715db/brooks_self-portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)