Jazz Has Never Looked Cooler Than It Does in This New Exhibition

These evocative images by photographer Herman Leonard call to mind a bygone era

In post-World War II America, the big bands of the Big Apple were no longer in full swing. Pioneering jazz artists had taken their talents underground, abandoning the glitz and gaudiness of sprawling orchestral groups in favor of more intimate ensembles.

These intrepid renegades made music in seamy clubs and narrow alleys, without all the pomp and bunting of yesteryear. Adventure and experimentation saturated the midnight air: the meandering improvisations of bebop and cool jazz had taken root in New York City.

Into this hopping scene stepped Allentown, Pennsylvania-born journeyman Herman Leonard, an eager shutterbug who, at the time of his 1948 arrival in Greenwich Village, was just coming off an invaluable one-year apprenticeship in the service of portraitist par excellence Yousuf Karsh.

Karsh, best remembered for his stark black-and-white depictions of such notables as Salvador Dali and Martin Luther King, Jr., taught the 25-year-old Leonard many tricks of the trade, impressing upon him among other lessons the wondrous potential of an off-camera flash.

Drawn by jazzy undercurrents which at once perplexed and fascinated him, Leonard could hardly wait to turn his lens on New York’s cadre of cats. Happily, as the National Portrait Gallery’s senior photography curator Ann Shumard recalled in a recent interview, the gung-ho photographer’s timing was positively impeccable.

“He was in New York at the moment that that music is bubbling up,” she says, “and the performers that will become household names in the future are just getting their start.”

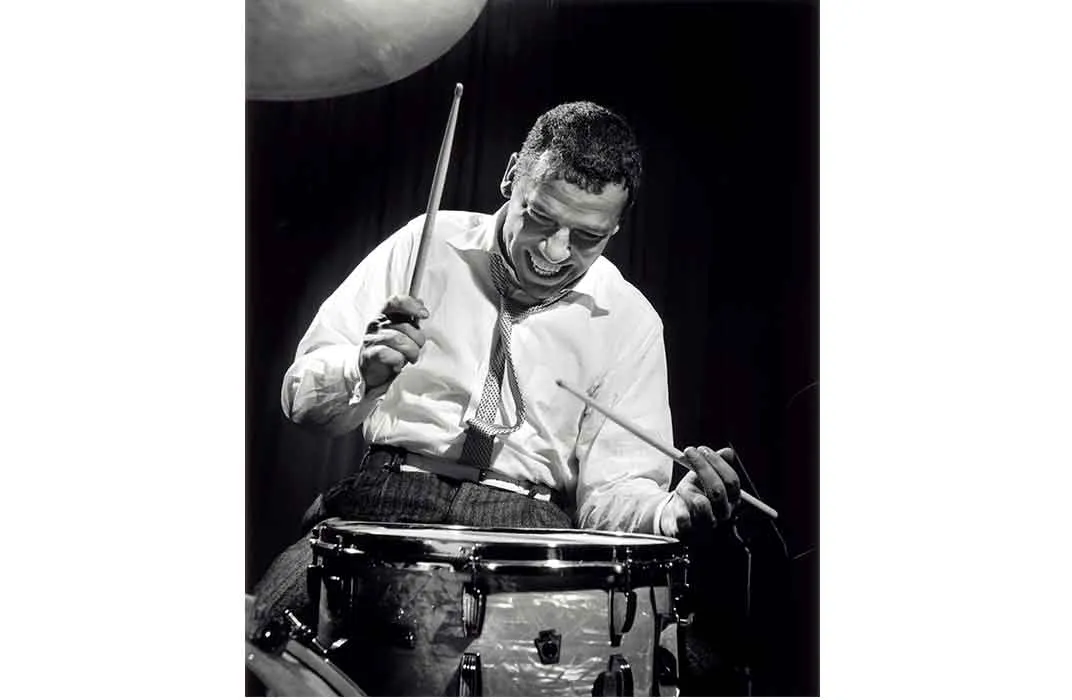

These luminaries, whose ranks included dusky-voiced chanteuse Billie Holiday, crack drummer Buddy Rich, and trumpet maestro Louis Armstrong, proved surprisingly accessible to Leonard and his trusty—albeit clunky—Speed Graphic camera.

Through a series of shrewd quid pro quos with local nightclub impresarios, Leonard was able to gain entrance into the circles where his subjects moved.

“He sort of bartered with the club owners,” Shumard says, “offering to take pictures that they could use for publicity, and that the performers themselves could have, in exchange for letting him into the club.” Leonard’s keen aesthetic eye ensured that such offers were frequently accepted. As Shumard puts it, “There wasn’t any doubt that this was a win-win for everybody.”

Inspecting the images in question, now on display at the National Portrait Gallery, one can instantly intuit just what the curator meant.

The artists in Leonard’s photographs are caught in moments of splendid isolation, their focus locked unshakably on their music, their every muscle fully engaged. In one shot, Billie Holiday’s reverent gaze is lost in the middle distance, the supple curved fingers of her dark-nailed hands caressing the air on either side of her mic stand.

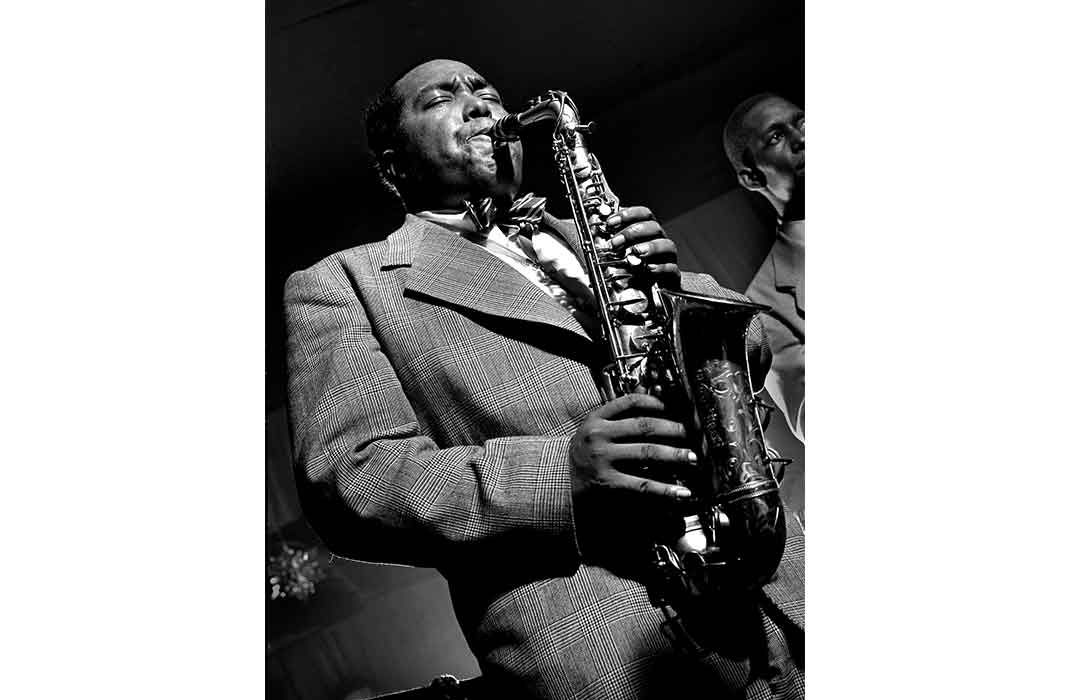

In another, Charlie Parker plays, his brow knitted, his lips pursed tightly about the mouthpiece of his alto sax, his eyes closed, captivated in a dream of his own making.

In a candid portrait of songstress Sarah Vaughan, one can practically hear the dulcet notes wafting forth from her open mouth.

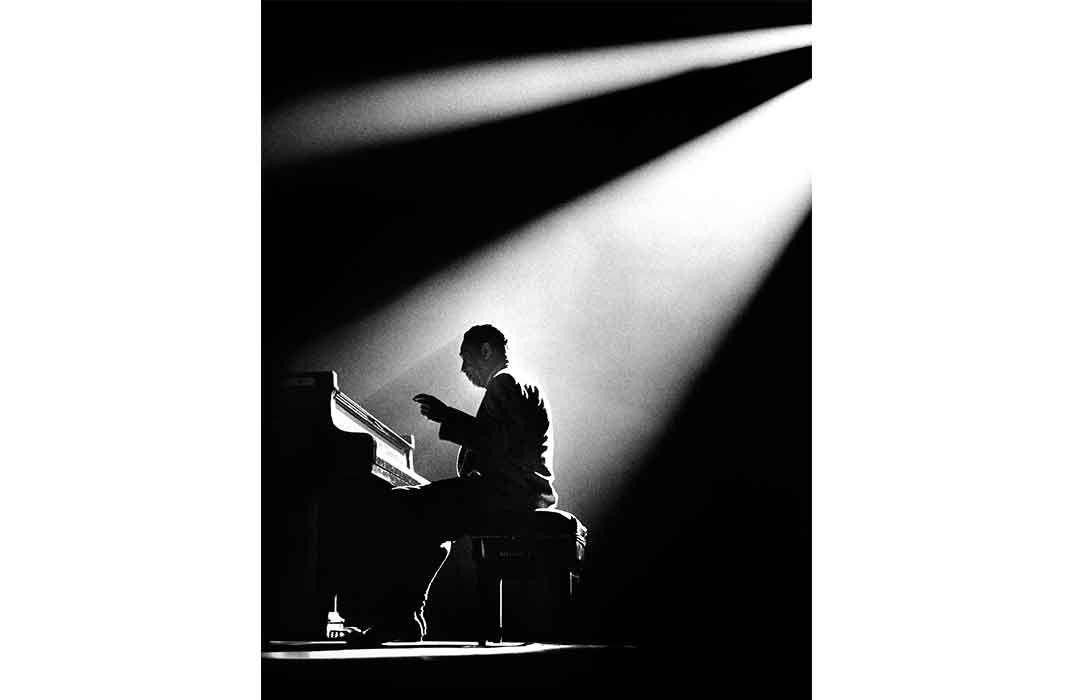

As Shumard observes, the organic, unstaged vibe of Leonard’s photography belies its creator’s fastidious preparedness. “One might assume from looking at the pictures that he just sort of showed up the night of the performance and snapped away.” Not the case, she says. “There actually was a lot more thought and preparation that went into those sessions than one would gather from looking at the pictures.”

While it is true that the bulk of Leonard’s jazz photographs were captured at live shows, he always made sure to plot his images out in advance, during rehearsals. In the comparatively laid-back atmosphere of such preliminary sessions, Leonard could experiment with the placement of his off-camera lights, which, when showtime came, would complement the house lights in a striking way, dynamically setting his subjects off from the background.

“There’s almost a three-dimensionality to the images,” Shumard says. “There’s an atmospheric effect.”

In Leonard’s portraits, the expressive potency of bygone jazz legends will forever be preserved, the passion and poise of these artists immortalized for the ages. It is apropos that the museum has chosen to bring these photos to light so close to the September opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, for jazz is a reminder of the degree to which African-American culture has shaped America’s distinct artistic identity.

It is Shumard’s wish that the exhibition will strike chords both familiar and unfamiliar in the hearts of wandering gallery-goers. “I’m hoping that first of all, they’ll see images of people they know, and will be entranced and delighted,” she says, “but I am also hoping they’ll be drawn to some of the images of people who are less familiar, and maybe take a little dabble and listen to the music.”

Patrons won’t have to go very far to get their jazz fix: on October 13, as a part of the museum's Portraits After Five program, live jazz will be performed in the museum’s Kogod Courtyard, as Shumard and fellow curator Leslie Ureña conduct tours of the Herman Leonard show inside.

At its core, Leonard’s work represents an all-inclusive celebration of jazz, in all its spontaneity, syncopation, and sway.

Indeed, it is the bared humanity of Leonard’s subjects that lends them their power, and that makes them so perennially compelling.

“The vitality of these performers,” says Shumard, “the excitement their music generated, made them ideal subjects for photography.”

"In the Groove, Jazz Portraits by Herman Leonard," featuring 28 original photographs taken between 1948 and 1960, will be on display at the National Portrait Gallery through February 20, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/07/b007207f-0314-408b-a5b0-141fa8847aed/billie-holidayweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/82/b0826996-b551-4335-b472-990f17566e0f/sarah-vaughnweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)