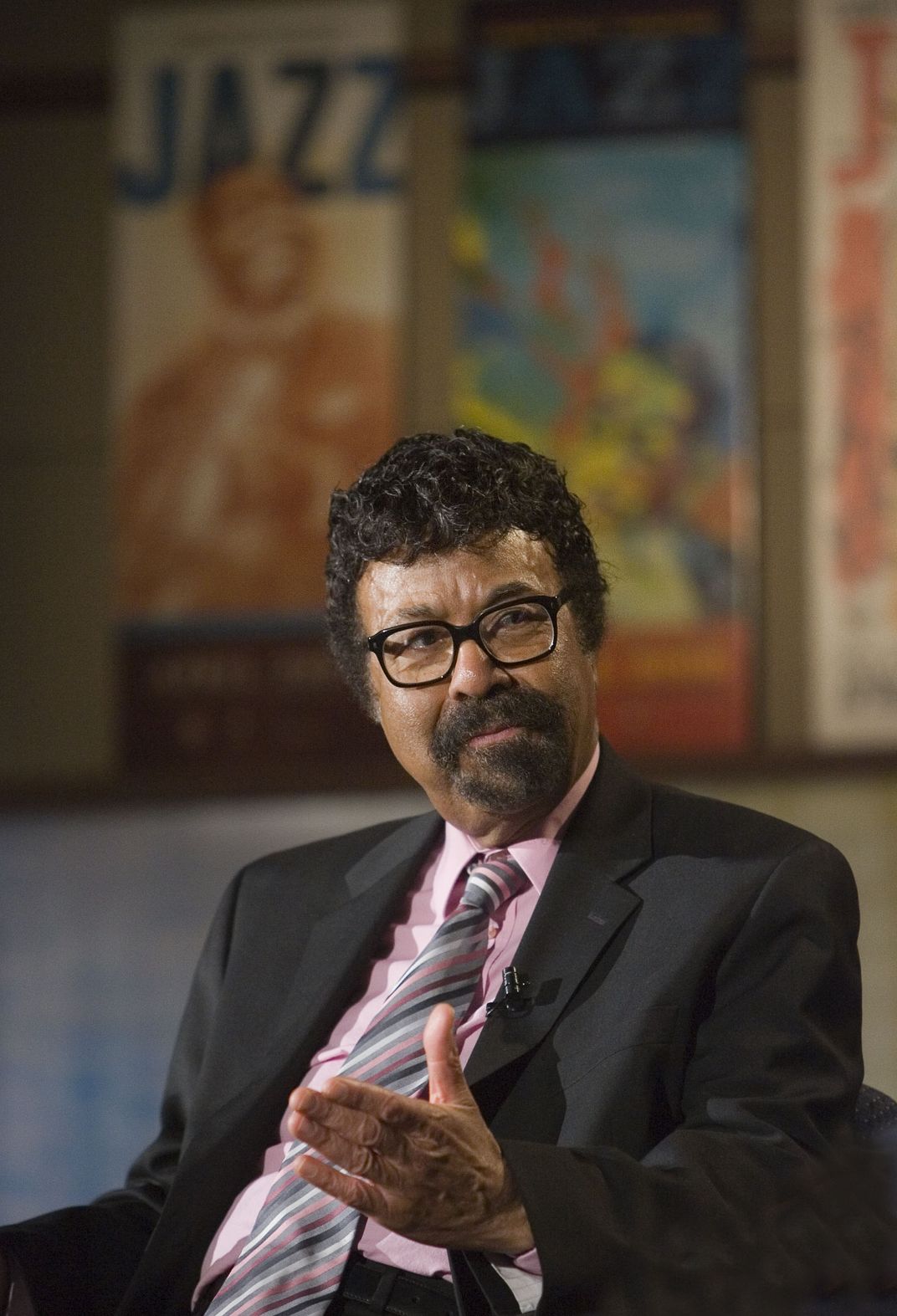

Jazz Legend David Baker’s Soaring Legacy

Smithsonian’s maestro, a founding director of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, has died at the age of 84

David Baker had one request when his former student, John Edward Hasse, the National Museum of American History's curator of American music, asked him to become the musical and artistic director of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra (SJMO)—he would only do it if Gunther Schuller, Baker's mentor, was named his co-director.

“He wanted to be respectful of his elder and someone who was very eminent in the field, that's how generous spirited he was,” Hasse recalls of Baker, who died at his home in Bloomington, Indiana, at the age of 84 on Saturday, March 26.

Though the renowned and prolific composer, conductor, performer and educator was loyal to his alma mater, Indiana University, he considered the Smithsonian Institution his second home. During his 20-plus years with SJMO, he helped build its extensive music library of more than 1,200 pieces. He also took Smithsonian’s Duke Ellington Collection off the archival shelves to teach and perform the great Jazz legend's music, eventually leading an Ellington tribute series to honor the centennial of Ellington's birth.

As Hasse puts it, “He helped establish its musical and public identity as an ensemble that explored the history of exceptional jazz—consistent with the concept of Masterworks—with a standard of excellence that inspired the musicians in the band and the audiences that came to hear them.”

The musical pioneer was born on December 21, 1931, in Indianapolis during a time of strict segregation. One of the reasons he first gravitated toward jazz was because it was one of the few areas that was accessible to him.

“People tend to excel in the areas that are open to them so at that time a black was expected to play religious music, rock n roll or jazz,” Baker once told Indiana University’s public radio station WFIU. His teachers at the all-black Crispus Attucks High School encouraged his interest, teaching him fingerings and surrounding him with music, he told the National Education Association in 2007, as Billboard reports.

Baker set his sights on becoming a trombone player in an orchestra, and his talent led him to perform with jazz luminaries such as Stan Kenton, Maynard Ferguson, Lionel Hampton and Quincy Jones.

In the early 1950s, Baker attended Indiana University, where he earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in music education. Students caught practicing jazz would be kicked out of the practice room then. But just a short ten years later, Indiana University’s School of Music invited him back to start its jazz studies program. He accepted the offer, becoming the school of music's only black faculty member, Indiana Public Media reports.

At Indiana University, Baker showed how jazz could be taught with an academic rigor, and during his prestigious career, he continuously elevated its field of study, teaching jazz pedagogy, theory, improvisation and history.

“We were of the notion that jazz was America’s music,” Baker told the Indiana Daily Student in 2012. “I mean, if we’re talking about music that was born here, it would be music that had come out of slavery, that had come out of Black Prohibition, all those early years when blacks were not allowed to go to the movies, could not get into most schools."

The day Smithsonian learned it would get funding for SJMO, Baker and his students at Indiana were performing a concert for a conference in the American History Museum’s Hall of Music. They were performing Duke Ellington's music, working from a trove of the jazz great's music manuscripts that the museum had recently acquired.

“Here he was in our museum conducting Ellington’s repertory on the same day we learned we got the funding,” Hasse says. “He was electrified when he heard this news.”

Baker and Schuller served as co-conductors for five years, and then Baker took over as SJMO’s sole conductor and artistic director in 1996, concluding his tenure as SJMO's artistic and musical director in 2012, when he was named maestro emeritus.

As Kennith Kimery, the executive producer of the orchestra put it, Baker was a musician's conductor. "He got music that could have been considered 'museum music' to come alive and breath in a way that others might have stifled," Kimery said.

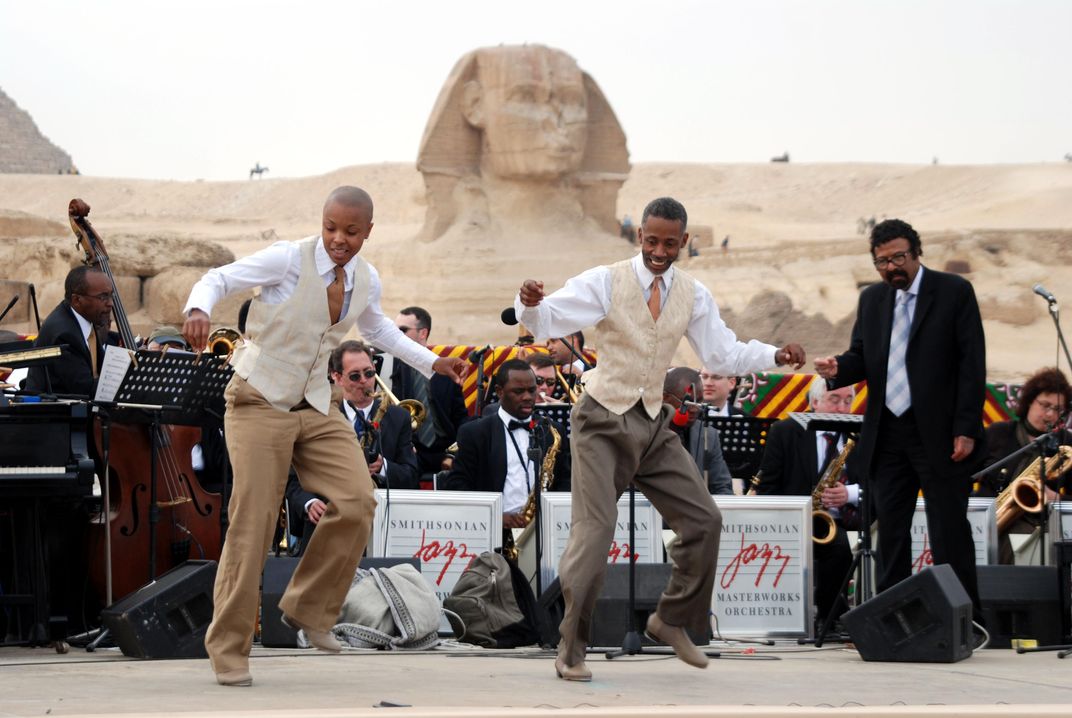

One of the orchestra's more memorable performances under Baker was when it traveled to Egypt in 2008 to play at the Cairo Opera House, Alexandria Opera House and the Pyramids.

Among Baker’s numerous recognitions, which include being nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and being named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master, he received Smithsonian’s highest honor, the James Smithson Medal from the Smithsonian Institution in 2002.

Despite his many accomplishments, though he is perhaps best remembered as a mentor. As Kimery says, after 2012, Baker and and his wife Lida, a flautist, were always ready to help with advice. And when Hasse visited Baker in Indiana last summer, he was still working with his Indiana students.

As Quincy Jones wrote in the forward to David Baker: A Legacy in Music: "[H]e always chose his teaching and his students as his principal calling. In a society that most commonly rewards glamorous careers with a focus on highly visible personalities, the choice to dedicate one's life to helping others achieve their aspirations is a mark of a truly selfless and kind person."