JFK’s Presidency Was Custom Made for the Golden Age of Photojournalism

A new exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum concentrates on the White House’s most photogenic couple

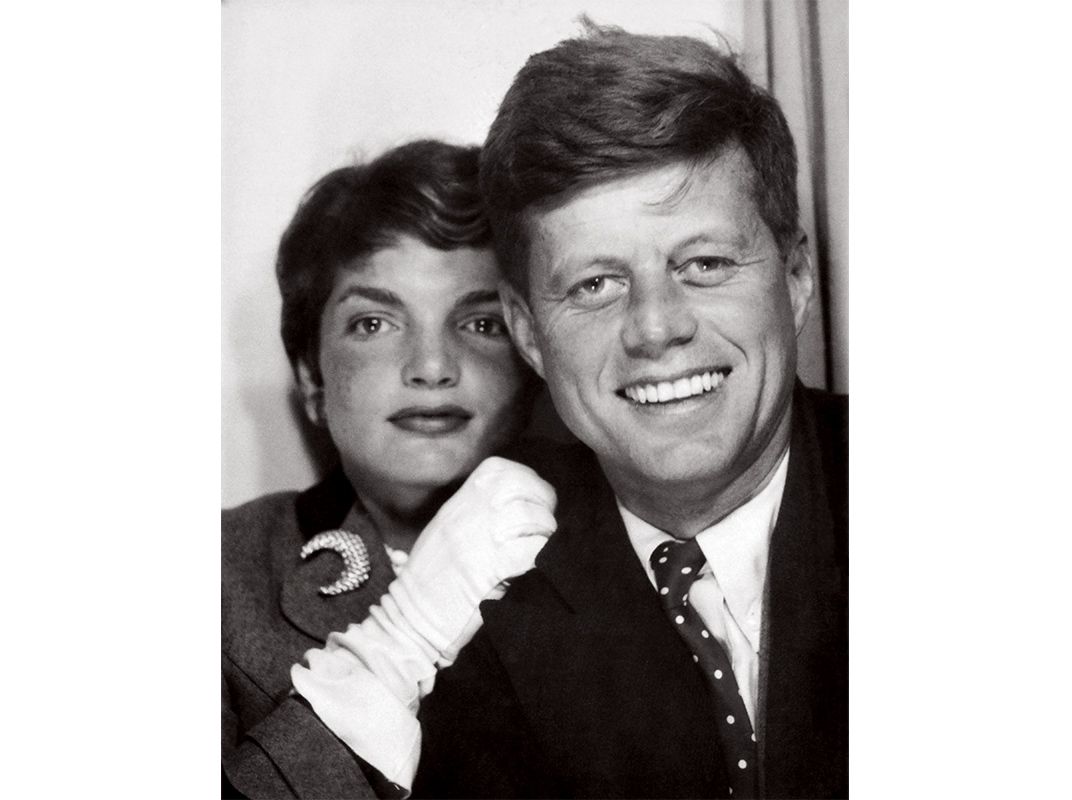

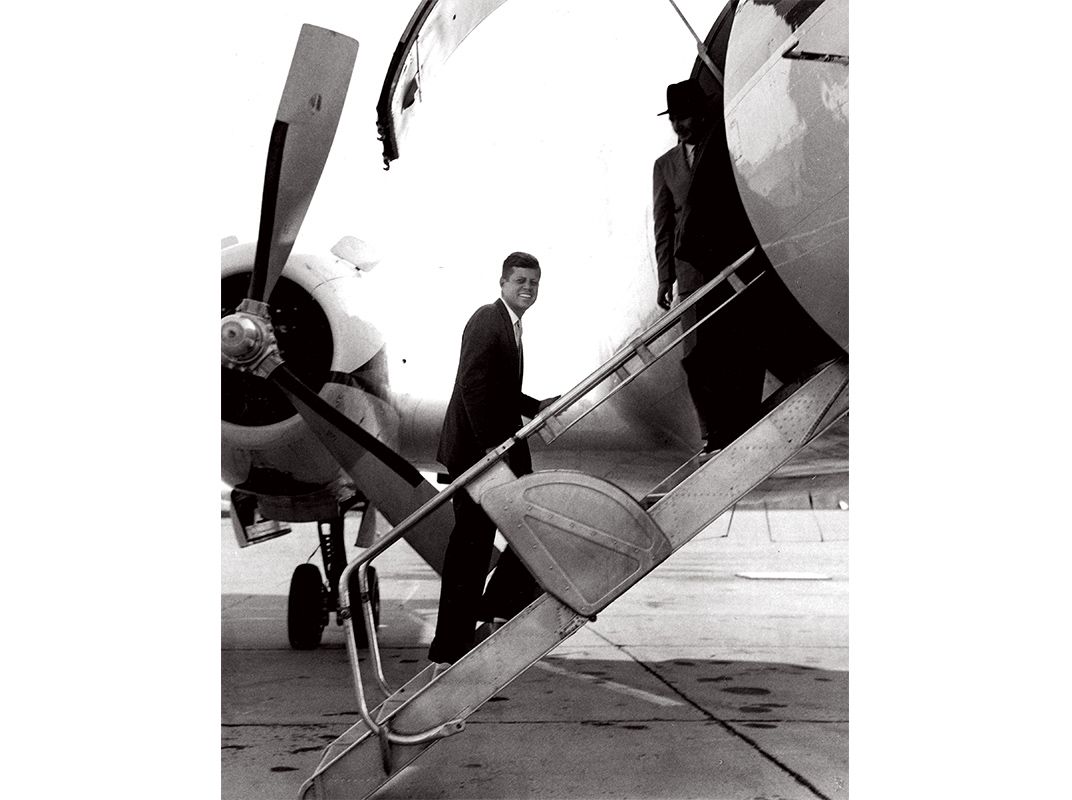

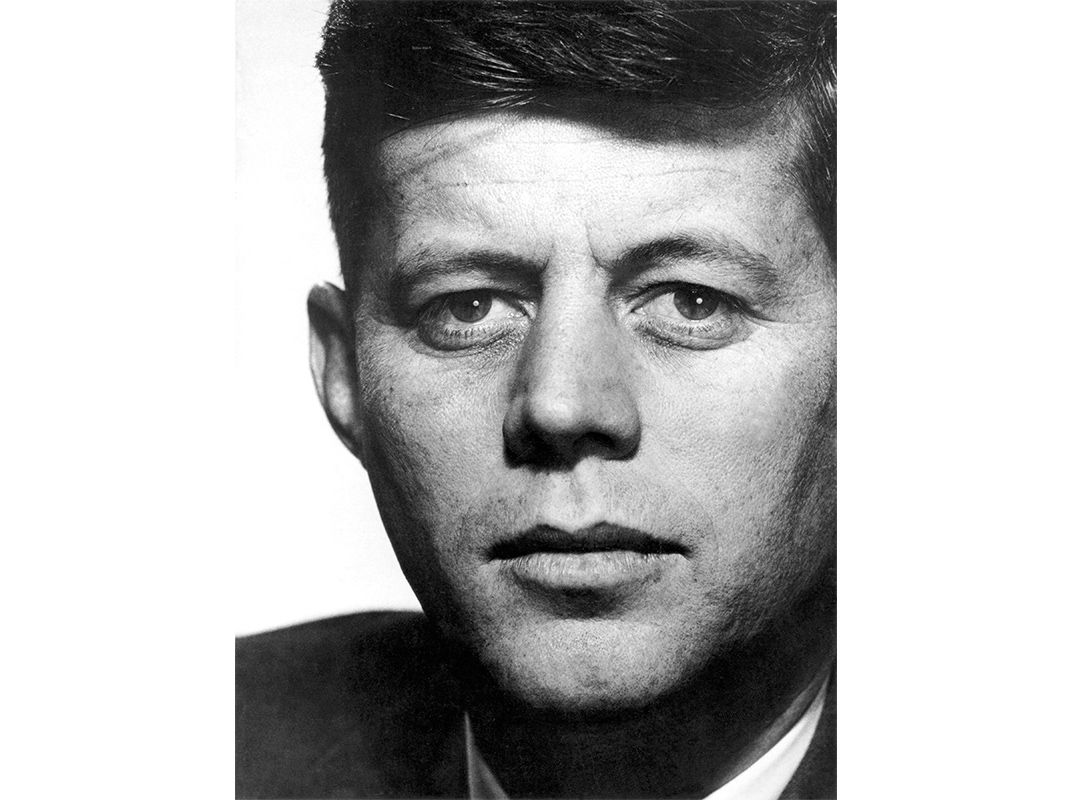

The golden age of American photojournalism arose just about the time one of the most photogenic couples took residence at the White House. President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy became the most photographed political couple to date when the brief reign, some called Camelot, began in 1961.

As the centenary of Kennedy’s birth this month is celebrated across the country, one of the first exhibitions to share his legacy is “American Visionary: John F. Kennedy’s Life and Times” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“This is an exciting day for us,” says Stephanie Stebich, recently installed director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “It’s one of the premiere events in the JFK centennial. It’s a remarkable exhibition.”

More than that, it had personal resonance for her.

“I’m standing before you in part because of President Kennedy,” Stebich says. Her late father decided to move his young family to the U.S. after being inspired by a 1963 Kennedy appearance in Frankfurt, Germany.

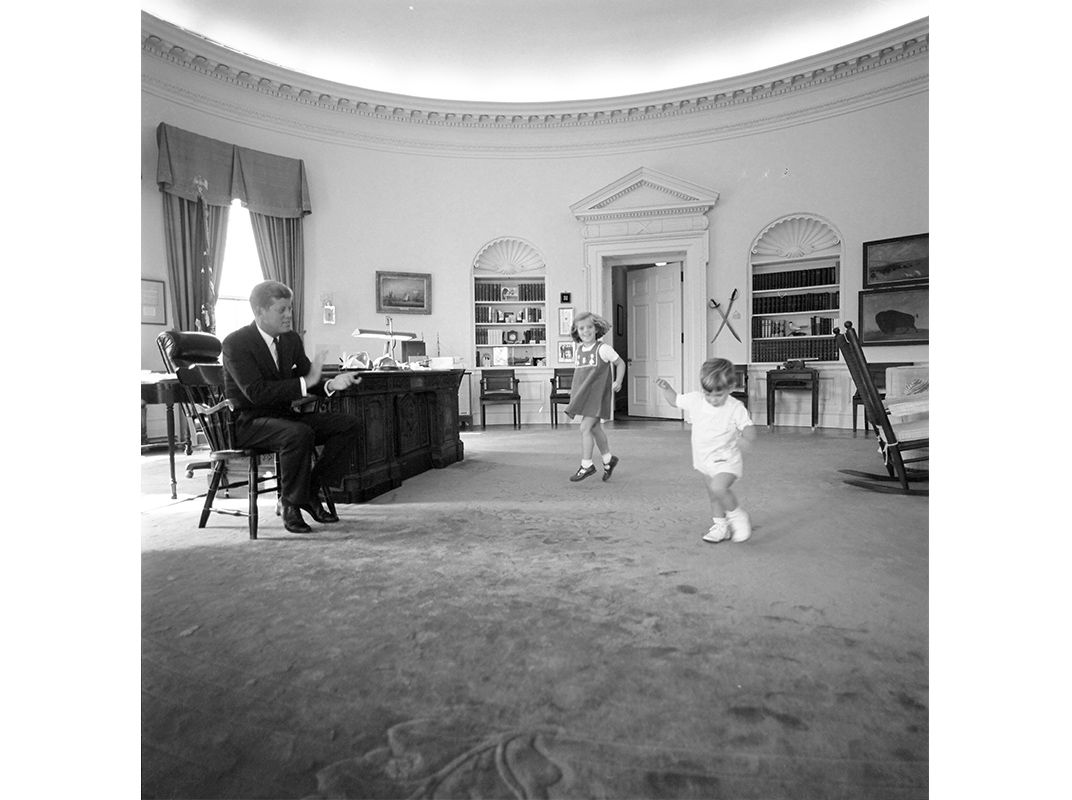

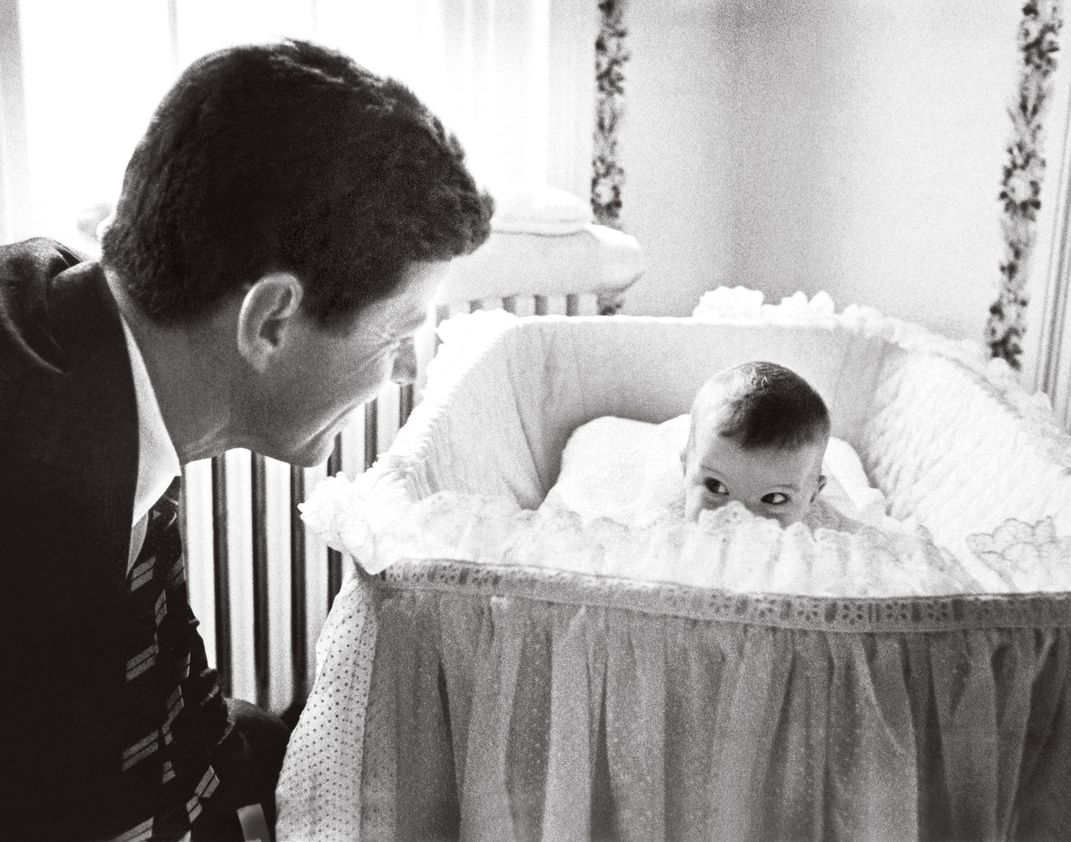

The exhibition includes the expected, iconic images of the 35th presidency, from toddlers cavorting in the Oval Office, to tense moments of global decisions to glamorous evenings entertaining in the East Room. But it also includes rarely seen pictures from the family collection of a young Kennedy growing up in Massachusetts, the family in Hyannis Port, and just a few images to indicate the national grief of his shocking assassination at 46.

“The exhibition covers a unique moment in American history when politics and the media found common ground in the figure of JFK,” says John Jacob, the museum's curator of photography. “It was a golden era of photojournalism—an exciting, even glamorous profession with the power to influence the course of political events.”

Photographers supplying a steady stream of images to general circulation picture magazines such as Look and Life “made John F. Kennedy’s vision for America real to its citizens as a sophisticated world power engaged in building a bright future,” Jacob says. At the same time, Kennedy operatives were savvy enough to know how such photographs helped advance their vision of a vital new America.

The 77 largely black and white images in “American Visionary,” gathered from the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, Getty Images, private collections, and the Kennedy family archives, are themselves culled from the nearly 700 images chosen to be included in the just-published commemorative book of Presidential speeches and essays, JFK: An Image for America, edited by nephew Stephen Kennedy Smith and historian Douglas Brinkley.

The photographs in the nearly 500-page book, as well as those selected for the exhibition, were curated by longtime photojournalist turned author and director Lawrence Schiller, who was among the scrum of photographers covering that political era more than a half century ago.

“We went through 34,000 photographs,” says Schiller, whose previous work includes the 1973 picture book Marilyn with Norman Mailer and the 1982 film version of Mailer’s “The Executioner’s Song.” It was the 300 JFK related photographs he gathered for a reprint of Mailer’s Esquire essay “Superman Comes to the Supermarket” that caught the eye of Smith, who was gathering his centennial collection of speeches and essays.

“Stephen liked the book and he came to me,” Schiller says. “He said, ‘I’d like to have eight or 10 great pictures in it.’ And I looked at him and said, ‘What do you mean, eight or 10 great pictures?’”

Schiller knew the wealth of pictures available both of the Kennedys and their family and the era in which they lived.

“It was an interesting challenge,” Schiller says of the 34,000 images they sifted through. “And they were not all just pretty pictures. We wanted images that told the story.”

“You need to put JFK in the context of the time in which he lived,” he says. “And then the question was: How do you make JFK relevant to today? How do you bring him to an audience, a majority of which maybe was just born when JFK was out there in Appalachia and all over the country campaigning?”

The campaigning begins early, with the young politician meeting longshoreman union bosses in 1946 during his first year as a congressman, getting used to the bright lights of cameras shooting a commercial for his 1952 Senate run, or that same year getting ready to meet a long line of women who wanted to shake his hand at a campaign event in Worcester.

“His father kept pounding into his head: If you win the women’s vote, you’re going to win the election,” Schiller says. “And the women’s vote then weren’t young people, they were upper middle class women. That to me is the picture: All of them all lined up.”

Things began to accelerate with the 1960 race, and we see the candidate standing atop a sedan to address a road of coal miners in West Virginia, greeting neighbors at Nantucket Sound, and conferring in private with his brother and campaign manager, Robert F. Kennedy.

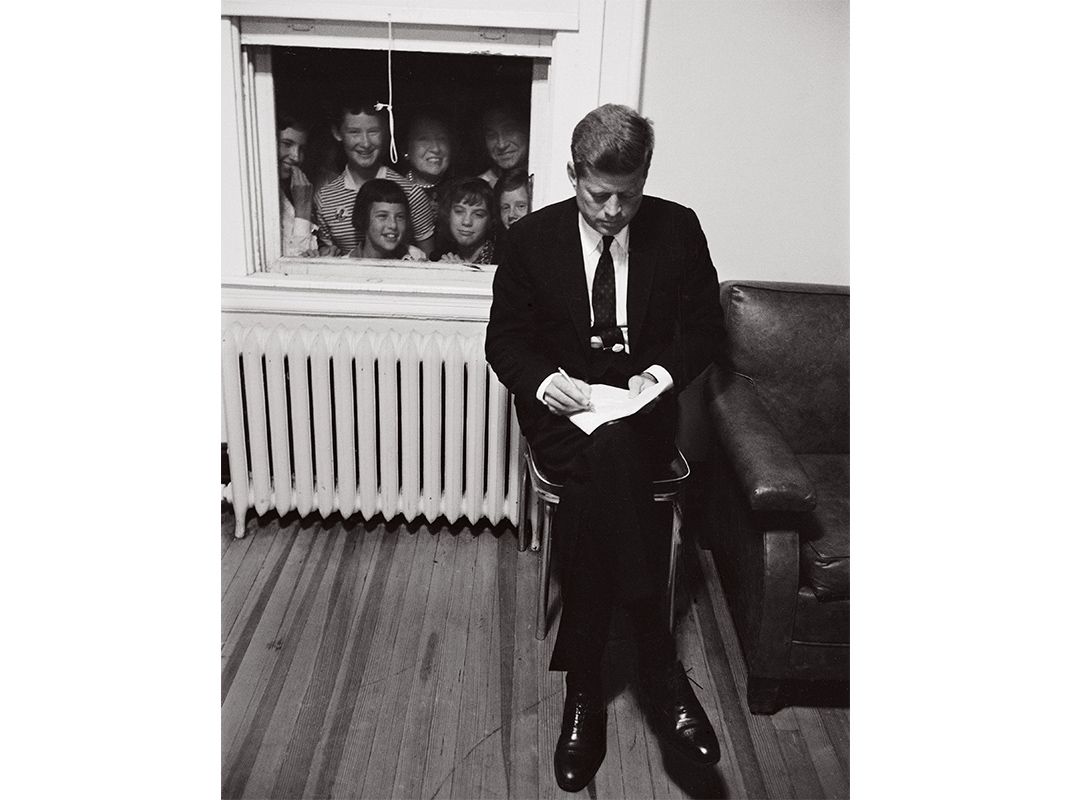

One of the pictures that is said to be a favorite of his daughter Caroline has the presidential candidate working on a speech in Baltimore while a group of excited young people watch him do so from outside through a window.

In office there are shots of world leaders with which JFK conferred, including Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschchev, though Shiller says, “from what I’ve been told, he was more interested in meeting Jackie than he was talking to JFK.”

Future leaders are glimpsed, as well, as in the famous shot when 16-year-old Bill Clinton, in Washington to attend the American Legion Boys Nation, shakes hands with the president that would inspire him.

There were tense, solitary moments in the White House captured in photographs by Jacques Lowe. But the images of Kennedy standing, his hands down on a table, leaning down, may have been misleading, Schiller says. “Why is he hunched over like that? Because it really helped his back. He wore a back brace and he was always like this because he could stretch himself out.”

There was an emphasis in bringing culture to the White House, seen in photographs showing Pablo Casals performing in the East Room, or the first lady smiling beneath the Mona Lisa (which was on loan to the National Gallery of Art in early 1963) or examining plans for historic preservation of Lafayette Square across from the White House—wearing the pink suit she’d wear a year later on that fateful day in Dallas.

“The most difficult of this exhibit for me was the tragic death of JFK, his assassination,” Schiller says. “I thought less is more. How do I tell this story in its simplest way?”

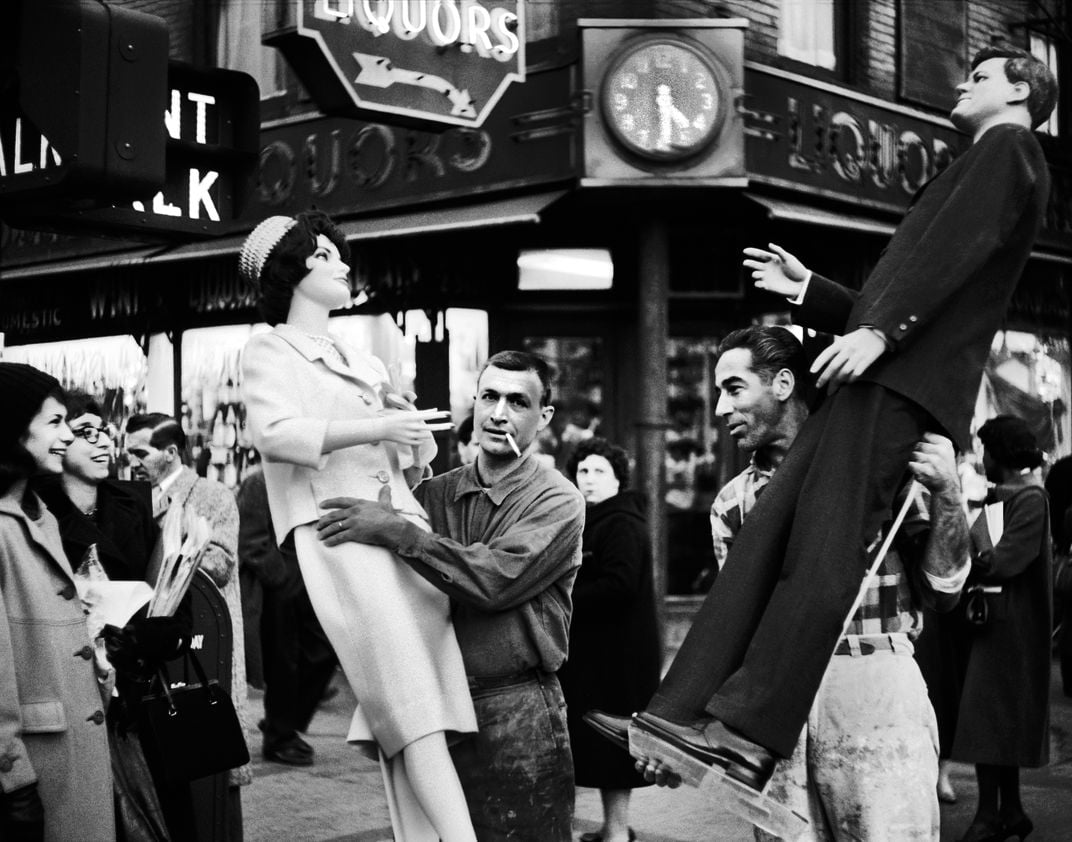

He uses just a handful of pictures—the couple’s arrival in Dallas, a bystander’s picture of the passing motorcade, Walter Cronkite delivering the grim news, a stone-faced former First Lady following the state funeral and spontaneous memorials that appeared in New York store windows, in which pictures of the late president were adorned with ribbons and flags. In death as in life, he was remembered in pictures.

“American Visionary: John F. Kennedy’s Life and Times” is on view through September 17 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Several Smithsonian exhibits and events marking the centennial of JFK’s birth. They include: a pastel portrait by Shirley Seltzer Cooper at the National Portrait Gallery May 19 through July 9; an event of specially commissioned music by Citizen Cope and Alice Smith, “America Now: JFK 100,” June 17 in the Kogod Courtyard; and the National Museum of American History will display nine Richard Avedon photographs of Kennedy and his family from 1961 within its “The American Presidency” exhibition May 25 to August 27.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/a5/99a51d8f-451d-42ac-b074-b69d82e01a70/unknown_traveling_europe-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/77/ca779df8-5847-4619-9f79-e463554ab20b/crane.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/08/0a08367c-416d-4e75-93b7-cc669d1f9618/schutzer_first_couple_inaguration.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)