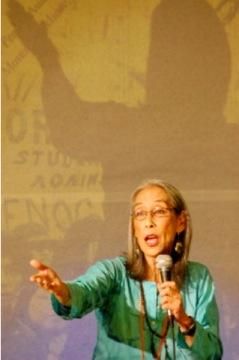

Joann Stevens: Arts Righting History

Japanese singer-dancer Nobuko Miyamoto will speak about her role in making a place for Asian Americans in music October 19th

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121017013044Sand_Thumbnail.jpg)

Before 1973, there was no Asian American music recognized in the United States says Nobuko Miyamoto, a Japanese singer-dancer credited with creating the nation’s first Asian American album, A Grain of Sand, with co-creator Chris Kando Iijima and William “Charlie” Chin.

“Now there are 200 taiko drumming groups in the U.S. representing a cultural voice for Asians,” she says proudly. “I see more (cultural) identity-based things taking place. There is an element of activism in the community now. ”

Cultural activism in Asian communities is the legacy of artists like Miyamoto, who in the 1960s and 70s, helped to popularize college campuses and communities create ethnic study programs and heritage recognition programs, says Theo Gonzalves, a Filipino scholar, researcher and musician who has studied the era and Miyamoto’s career. He said that today, most people take ethnic and cultural history programs for granted, unaware of the resistance they faced and how civil rights activists like Miyamoto helped make them possible.

“The idea of ethnic studies was to democratize higher education so that it opened up opportunities for the community at large,” says Gonzalves. Artists like Miyamoto “helped write Asian communities into the national narrative,” using music and art to tell the stories and histories of people who had been misidentified or largely excluded in American history up until that time.

“Art and culture is not just about entertainment. It’s about examining questions of history.”

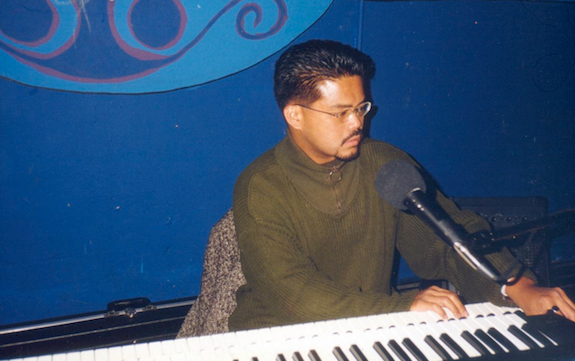

Miyamoto will participate in an upcoming panel discussion and program at the Smithsonian on October 19, featuring Afro-Filipino singer Joe Bataan to help foster and facilitate the recalling of this history, and what it was like when people of different ethnicities shared the same spaces and similar stories.

A native of Los Angeles, Miyamoto began her career as a dancer, studying with legends Jerome Robbins and Eugene Loring, “who taught me dance was a form of communication.”

She won featured roles in the “Flower Drum Song,” “The King and I” and “West Side Story.” An invitation to work on a film about the Black Panthers became a cultural turning point that immersed her in the social activism of the Panthers, the Young Lords and Asian activists, which is how she met Chris Iijima, helping to bring diverse culture and social services to their communities. Services provided ranged from breakfast programs for children to housing assistance and bi-lingual workers to record community problems.

“We sang at rallies and did gigs for Puerto Rican (activist) groups,” she says, sometimes singing in Spanish. But even the culture wars had moments of humor.

“We established an Asian American Drop-In Center in a bodega on 88th Street and Amsterdam Avenue,” Miyamoto recalls, “calling it Chickens Come Home to Roost in reference to a statement made by Malcolm X.”

“People started calling us the chickens, and would ask ‘can the chickens come and help us take over a building?’

The story of how Asian cultural activists confronted the sixties culture wars to gain a voice in the national narrative will be presented October 19 in a free, Smithsonian Asian Pacific American program at the National Museum of Natural History. Miyamoto will participate in a 6:30 p.m. panel discussion followed by a concert with King of Latin Soul singer Joe Bataan. The Smithsonian Latino Center and National Museum of African American History and Culture are co-collaborators.

Joann Stevens is program manager of Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM), an initiative of the National Museum of American History to advance appreciation and recognition of jazz as America’s original music, a global cultural treasure. JAM is celebrated in every state in the U.S. and the District of Columbia and some 40 countries every April.