John Singer Sargent became one of the most sought-after artists at the turn of the last century. Commissions rose for his lavish oil portraits but, as he wrote to a friend in 1907, “I abhor and abjure them and hope to never do another, especially of the Upper Classes.”

So at the age of 51, he took early retirement from oil portraits, says the art historian and distant Sargent relative Richard Ormond—“which is an extraordinary thing for an artist to do at the height of his powers.”

The talented artist, who was born in Florence to American parents in 1856, trained in Paris and lived most his life in Europe, wanted to devote more time to landscapes, travel and completing the murals he began at the Boston Public Library. “He wanted the freedom to paint his own things,” says Ormond, a dapper Brit in pinstripes. “But he couldn’t escape entirely.”

To satisfy lingering commissions and delight his friends, Sargent made his portraits in charcoal—a medium that allowed completion in less than three hours rather than the weeks or months his full-length oil portraits took. The works on paper showed all the facility of the psychologically informed and carefully drafted oils, but with a dash of the spontaneity charcoal gave him.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/d8/d4d8f1ca-defb-4a4d-b132-630d64a36e8d/lady_helen_vincent.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/f0/fff010ba-1e28-4356-aba8-aad3dd5bae05/exhsd21_daisy_fellowes_1.jpg)

Ormond, 81, the former director of the National Maritime Museum in London and deputy director of the National Portrait Gallery there, is a renowned authority on his great-uncle, having produced a comprehensive nine-volume survey of his paintings.

Once those were complete, “I decided to start in on the portrait charcoals, which are little known because they’re all scattered in private collections,” he says. “Museums that have rarely shown them, exhibitions occasionally include the odd one or two.” Yet there are about 750 in existence.

Ormond was the guest curator of the exhibition “John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal” held at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in 2020—the first such drawing show in more than 50 years. The exhibition offered a rare opportunity to view 50 of the portraits, many that hadn’t never been seen in public previously. “They came from private collections,” says the museum’s director Kim Sajet. “One of the most esteemed in fact being Queen Elizabeth herself from England. She lent a number of pictures.”

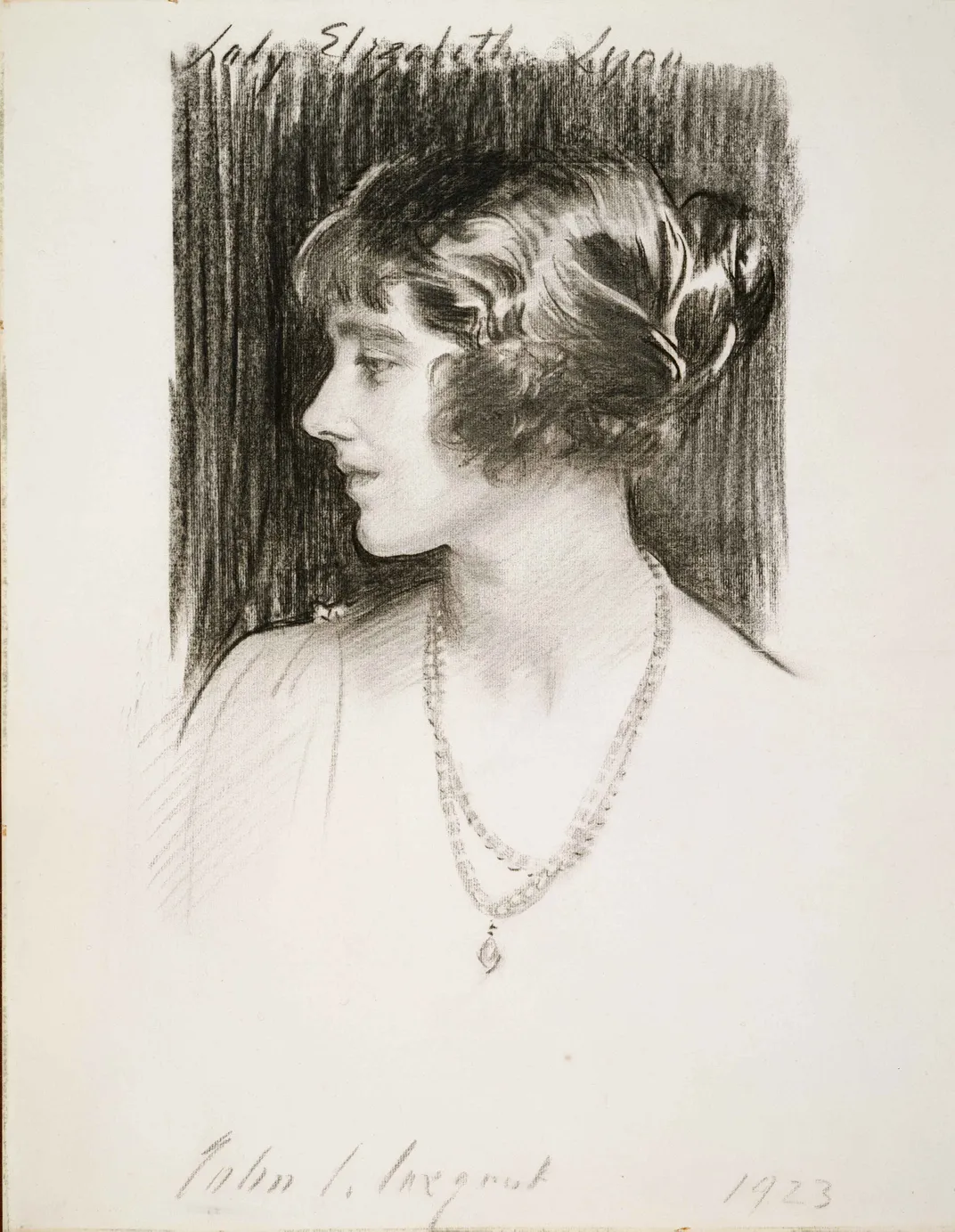

A private family picture was included—a 1923 profile of the Queen Mother, from the period when she was known as Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. “Sargent made the drawing the year she was married,” says Robyn Asleson, the museum’s curator of prints and drawings who helped to organize the show. “The crown didn’t know her brother-in-law would abdicate and she would become queen eventually.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0b/9c/0b9c7c86-ae5f-4a90-b47b-91879d2684a9/lady_diana_manners.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/67/d167d8cc-1f49-4bf0-b8be-da4851109cf1/gertrude_vanderbilt_whitney.jpg)

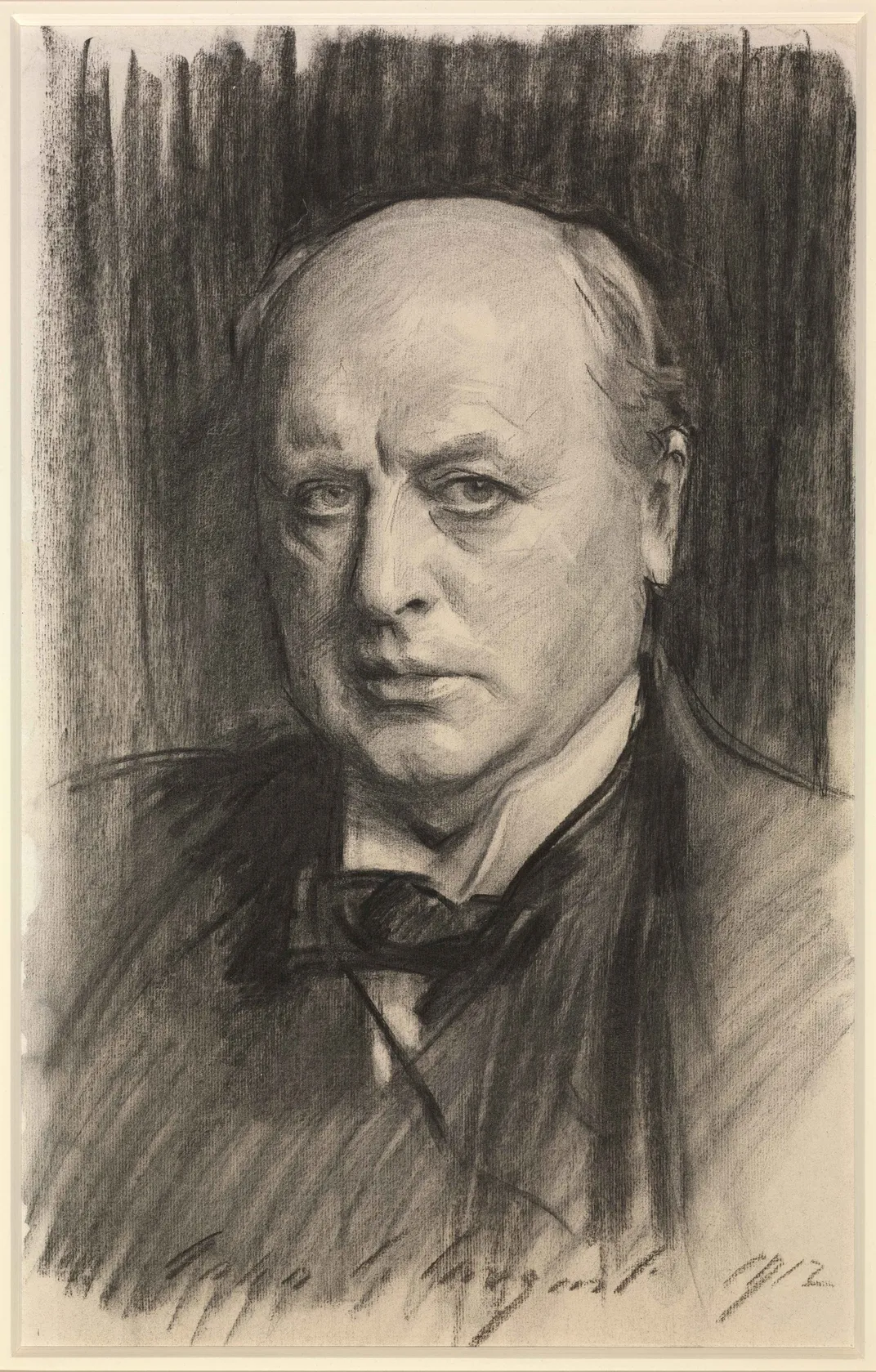

Also lent from the Palace is a portrait of the writer Henry James, a great friend of Sargent. “They met in Paris in 1884 and James, who is a little over a decade older than Sargent, became his great champion,” Asleson says. “Through his art criticism and writings, he really pushed Sargent’s career and was the one who urged Sargent to move from Paris to London, where he thought he’d have a good market.”

The James portrait was commissioned by the writer Edith Wharton, who, like Sargent, was dissatisfied with the result (“I think that points to the difficulties when you know someone so well, and you try to make a portrait of them and it’s impossible to encompass all you think and feel and know about him,” Asleson says). Sargent instead presented it to King George V in 1916, two weeks after James’s death at 72.

Like James, Sargent was seen as a major transitory figure between the traditional and modern worlds. His charcoals are faithful to the kind of sharply-observed psychological insights that would inform his oils, but also display a kind of freehand spontaneity, particularly in the vividly drawn backgrounds that make them a harbinger of more expressive things to come.

The exhibition was organized by the Portrait Gallery with the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, where it showed late last year in its ornate hallways.

“It felt very Victorian,” Asleson says of the Morgan’s presentation. “Our designers wanted to do something totally different so it’s not the same show, but also to convey this idea of modernity and freshness and lightness and spontaneity.”

The resulting yellows, peaches and baby blues on the walls, she says, “are quite different than anything I’ve seen with Sargent.”

“Because we’re a history museum we really have to make a case for the people we show, that they’re worth remembering, they’re important,” Asleson adds. “So, there is quite an emphasis in the labels on why they matter.”

The portraits are roughly arranged in various categories or interests. And most are notable. A hallway featuring performers of the era includes a 1903 view of a vivacious, long-necked Ethel Barrymore that may have some family resemblance to descendants, such as the contemporary actress Drew Barrymore.

Sargent advised another actress to discard an earlier charcoal portrait he’d done of her once he saw her perform in one of her famous one-woman shows. The brooding Ruth Draper as a Dalmatian Peasant shows all the pensiveness of her character. The result speaks to how his personal knowledge and interaction with a subject to really get at their core helped inform the resulting portrait, Asleson says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/e6/4ee67827-84b8-491f-87f6-85c84dbad8a2/ethel_barrymore.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/9b/309bef0e-52c5-47a3-84aa-7b8458a2ef9a/ruth_draper.jpg)

Sargent often made such drawings as gifts to their subjects, and signed them elaborately, “as a way of almost working off indebtedness to them for inspiring them or entertaining him or moving him,” Asleson says.

After seeing Barrymore perform in 1903, the artist wrote her a fan letter, “I would like to do a drawing of you, and I would be so honored to present you with the drawing afterward,” Sargent wrote. In the resulting portrait, Asleson says, “you see he’s almost dazzled by her star power and the limelight and the glamor.”

The highlights in the hair, often created by erasing the charcoal with bits of bread, show “he’s very good at the wavy hair,” Ormond says. “The fluency you see in his oil paints is equally true of his charcoals,” he says of Sargent. “He’s absolutely on it.”

But sitting for Sargent even for a few hours might have been “rather intimidating” for the subjects, Ormond says. “Someone would turn up in a new dress especially chosen for the occasion and he’d say, ‘I don’t want that,’” he says. “He stage-managed it, and he expected other people to play their part. The subjects, no matter how famous they were, were there to create a good figure to express themselves, so he could capture them,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/4d/194d2aba-9cbe-4f58-930d-2b33626b438a/kenneth_grahame.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/db/d5dbfe8e-18ab-45f3-bbde-256679bcdf8e/yeats.jpg)

“Sometimes, with some of the sitters, they were like rabbits in the headlights,” Ormond says. “‘No, that’s no good! You have to stand your ground,’ Sargent said to them. He expects an interaction, and we in a way are in the position of the artist, responding to these sitters and they’re playing their part … so it’s not passive,” he says.

The artist would charge around and make his marks, curse a mistake, or sit down to the piano to break the tension, Ormond says. “But he had those two hours to capture the essence of the person in the drawing.”

A gallery of literary figures features the James, but also a straight on view of Kenneth Grahame, author of The Wind in the Willows, and a glamour shot of W.B. Yeats commissioned as the frontispiece for the first volume of his Collected Poems in 1908 that the poet called “very flattering.”

A room of political forces has both the future Queen Mother and the future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, 15 years earlier when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer. The 1925 drawing of Churchill was one of the last works Sargent produced.

A room dedicated to artists and patrons includes a decimated Sir William Blake Richmond from 1901 and a rare 1902 Double Self-Portrait. “He didn’t like recording himself,” Ormond says of his great-uncle. “He was a private man. He liked doing other people, but didn’t like putting the searchlight on himself.”

Because the mostly larger-than-life 24- by 18-inch portraits are on paper, the Sargent show will be shorter than usual, just three months, because of the fragility of the material. Also, Sajet says, those who lent their pieces from private collections will be anxious for their return. “These have come out of people’s homes—or palaces in that case,” she says, “and they would like them back.”

:focal(288x137:289x138)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/24/5e246dc0-7596-482f-a753-c8a59073498c/sargent_mobile.jpg)

:focal(571x274:572x275)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/84/62847609-f093-4f98-a491-db60130d2ec0/sargent_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)