Journey to Mingering Mike’s Magical, Musical World

A new exhibition features the playful LP album covers of a man who built a make-believe musical empire filled with genius and joy

Lots of kids create their own fantasy worlds, populating them with monsters or superheroes—representations of friends and family, persecutors and allies, foils and alter-egos. For some, it’s a way of getting by when they don’t fit in, or of escaping the hard reality of their daily lives.

Mingering Mike was one of those kids with a vivid fantasy world. As a young man growing up in Washington, D.C. in the late 1960s, he didn’t think of himself as an artist. He was Mingering Mike—a made-up character for the musical world he inhabited in his mind. “Mingering” was jabberwocky, a mash-up of words he created. Mike wasn’t his real name, either. But even as he toiled behind closed doors—insulating himself from a sometimes chaotic home life and then a bit later from those who might report him for evading the Vietnam draft—he strove for stardom and recognition. Now, decades later, at the age of 64, his early fantasy-life creations are on display in the new exhibition "Mingering Mike's Supersonic Greatest Hits" at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through August 2, 2015

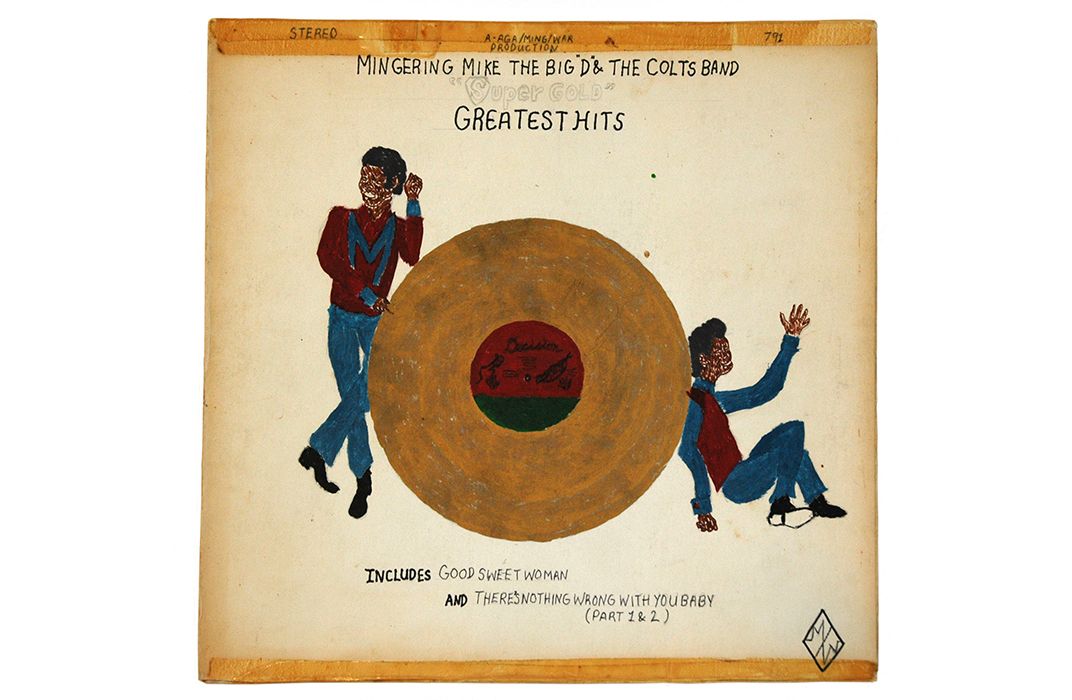

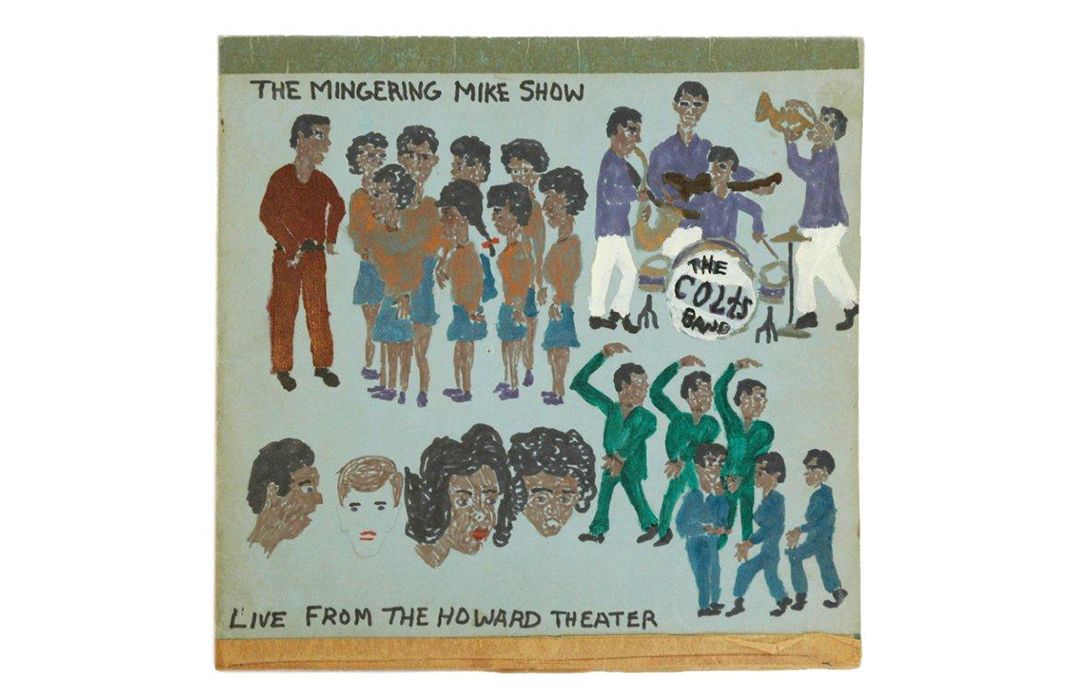

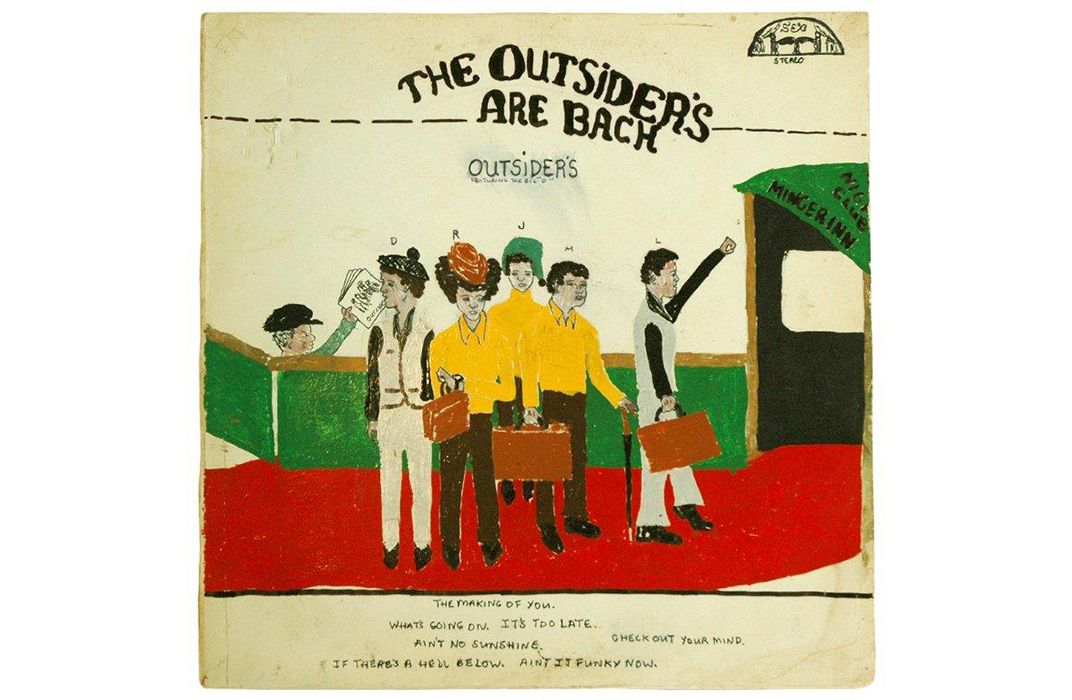

The works encapsulate a universe of real and imagined song recordings, made-up record labels, and vividly drawn faux album covers, complete with liner notes, fleshed-out themes and recurring musician-stars, and all with Mingering Mike as a central character. At the museum, they are being presented as relics and signifiers of a certain place and time, but also are celebrated for their art, wit and social commentary.

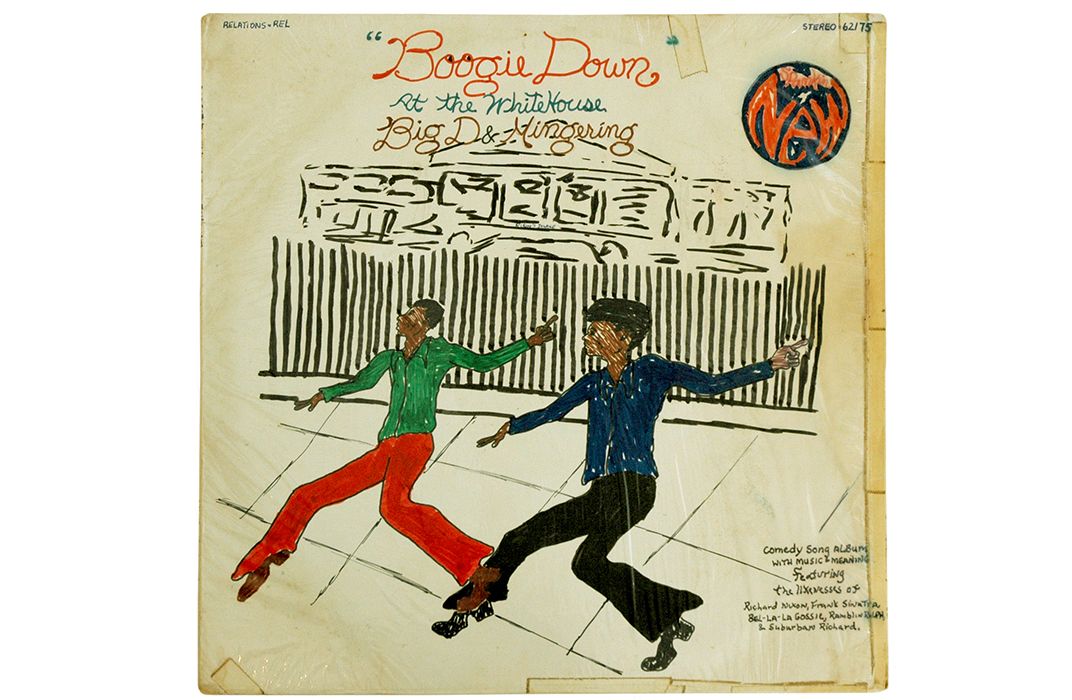

The works are accessible to anyone who’s ever fantasized about being a rock star, or who appreciates a sly sense of humor, music or history. Mingering Mike wrote songs, and occasionally acted out the fantasy by going over to his cousin’s house to freestyle—saying whatever came into his head—and laying it over the beat of hands rapping on a phone book and the percussion of his own voice. Cousin “Big D” became a frequent collaborator and character on Mike’s recordings, real and imagined.

Eventually, over a prolific decade between 1968 and 1977, Mingering Mike wrote more than 4,000 songs, created dozens of real recordings—on acetate, reel-to-reel, and cassette—and drew hundreds of faux labels and album covers for his real and imagined 45 RPMs and 33-and-a-third LPs, none of them ever released beyond the boundaries of his living room.

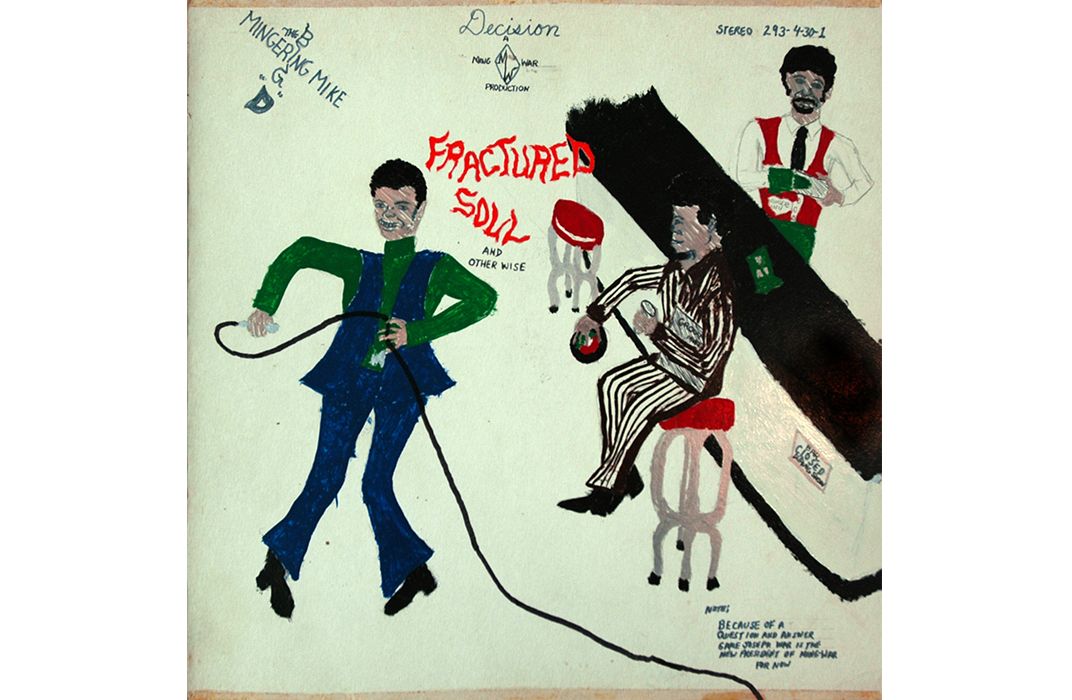

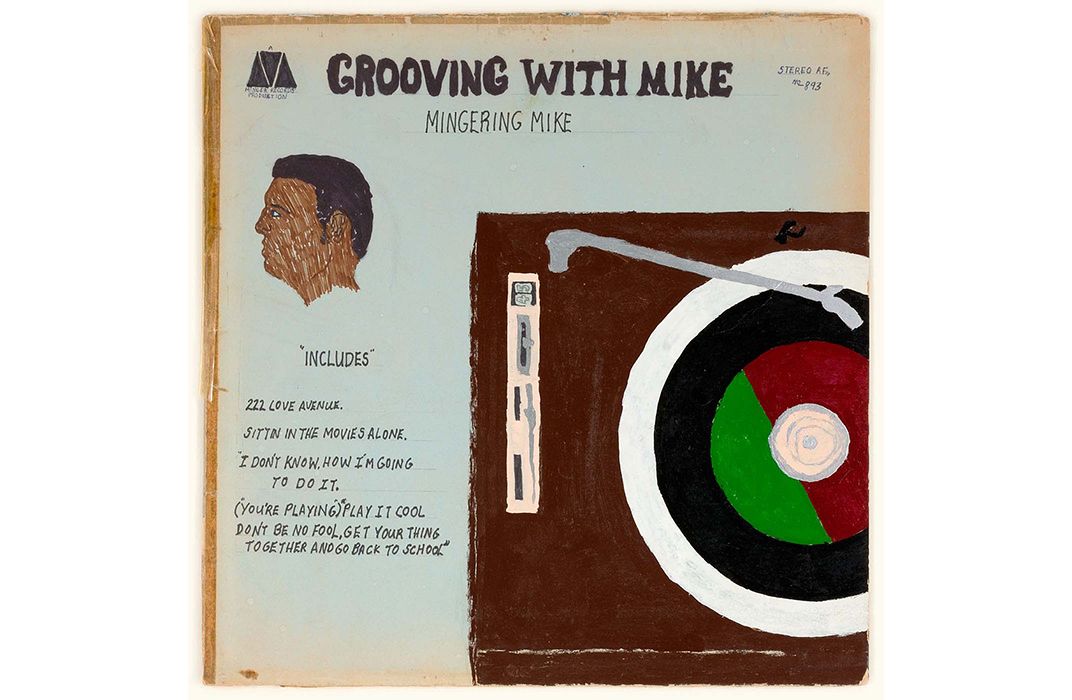

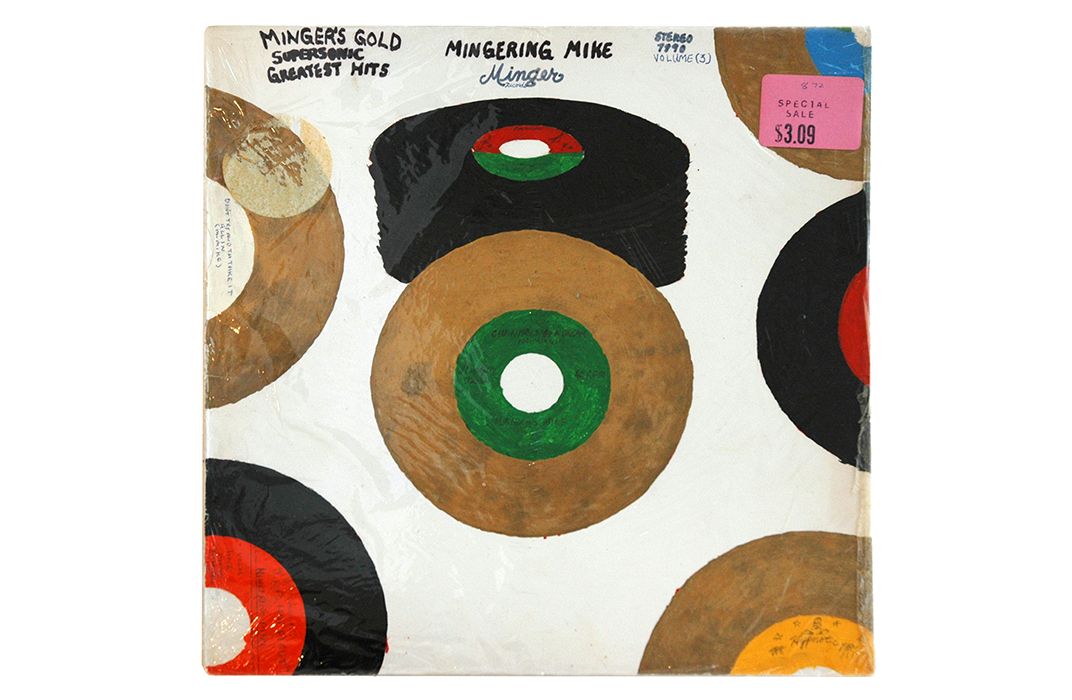

His hand-drawn LP covers and record labels are rendered as faithful replicas of the real thing, but made of posterboard or cardboard and cut to the square dimensions of an LP cover, or fashioned into circular-shaped 45s. The made-up label names include Sex, Decision, Green and Brown, Ramit Records, Gold Pot Records, and Ming War Records, among many others.

It never occurred to Mike—after all that work—that he eventually would lose the collection (which had been put away, like childish things, into storage), or that it would be found again by someone equally as passionate and driven. Or that they would join up like two Mingering Mike characters—one, a bearish and shy African American man who grew up in rough neighborhoods and the other, a lanky, thoughtful record-collecting white guy from a middle class Washington, D.C. suburb—inspiring the music and art worlds with their love for their endeavors and their mutual admiration.

By the time he was 18, Mike had lived in 13 neighborhoods around the nation’s capital. The District of Columbia of his youth was a gritty, urban place, hard hit by poverty and inequality. Several major downtown corridors were burned and looted over three days of rioting in April 1968 in the wake of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination.

Mike, a peaceful introvert who observed this simmering and sometimes boiling cauldron, was raised by an older sister, but all was not well at home, either, with her alcoholic husband adding an element of fear and chaos.

The boy escaped in part by watching TV—detective shows, "Hit Parade," and the dance-and-music-focused "Soul Train," a huge favorite. Local AM radio—WOOK and WOL, both of which played “black” music—inspired him. But Mike was a protean listener, citing Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Tony Bennett and Bing Crosby among his inspirations.

It all spoke to him. “You hear what artists say in the music," he says, "it sounds so incredible to you at that particular time in your life and you wonder if you can do things like that. That’s what music is all about—either the words or the melody, that’s what it’s all about, to be able to connect to someone. [And] “some people don’t even pay attention to it.” But he was drinking it in and trying in his own way to reach out.

Mike drew and crafted his first LP cover in 1968. Sit’tin BY THE Window by G.M. Stevens, on the made-up Mother Goose Enterprises Records. On the cover, a man with neatly trimmed hair, “G.M. Stevens,” wears a green T-shirt, dark pants and green socks. He sits with his chin on his hand, looking at you, possibly wondering what’s going on around him. Mike wrote liner notes and attributed them to “Jack Benny.” The notes reported that the musician had been “playing all the little chip joints this side of 16th and 17th street not where the White House is, he’s bend [sic] kick [sic] out of there three times and told never to come back."

Another of Mike's album covers that year was Can Minger Mike Stevens Really Sing, on the imagined Fake Records. There was a variety show-style LP cover, The Mingering Mike Show Live From the Howard Theater, which honored the real Washington, D.C. music venue, known for hosting jazz greats Duke Ellington and Billie Holliday in the 1940s and 1950s and that Mike frequented with a brother, who worked there.

Mike’s real world got turned upside down in 1969 when he was drafted in the Vietnam War. As he completed basic training in 1970, he decided the war was not his destiny, so he went AWOL. As he sat, isolated, keeping under the radar so he wouldn’t get turned in for draft-dodging, the songs and the art came tumbling out.

And just as R&B evolved from sweet love ballads and doo wop in the 1950s and early 1960s, to the message-oriented statement songs in the late 1960s and 1970s, so did Mike’s songs and art change and grow.

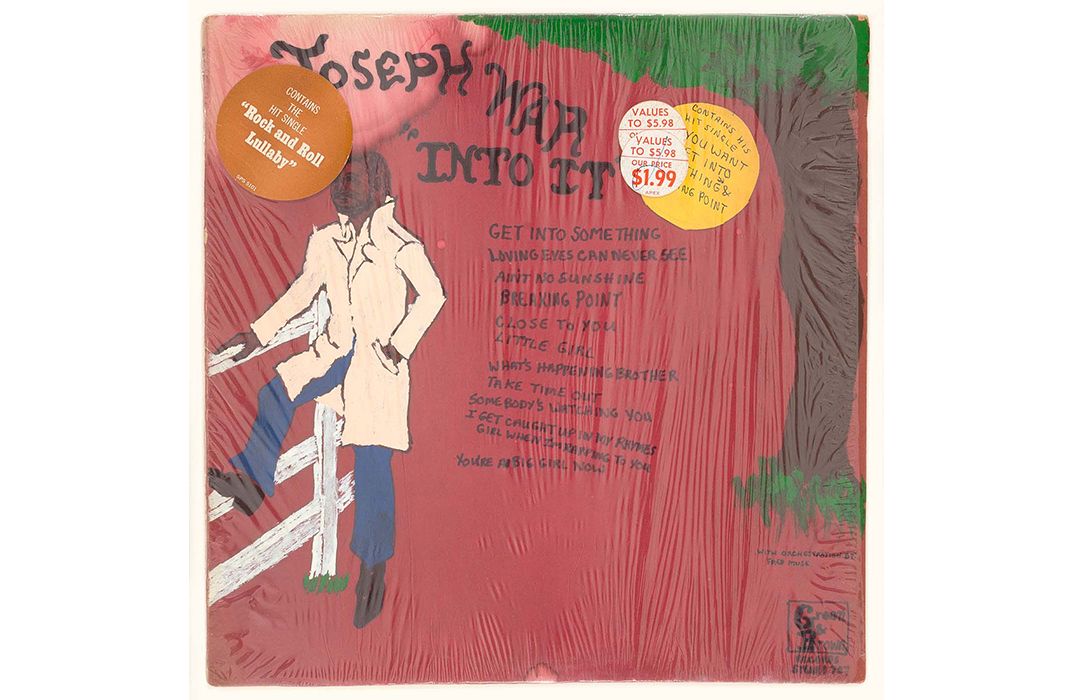

As he spent more time at home, and the war dragged on, his LPs often took on a more somber tone. There was the Joseph War character and musician, modeled on a cousin who had gone to Vietnam. Joseph War appears first as a tie-wearing, clean-shaven man with a high-fade haircut, and then, on others, evoking a skull-cap-wearing bearded Marvin Gaye and a Super Fly-ish Curtis Mayfield.

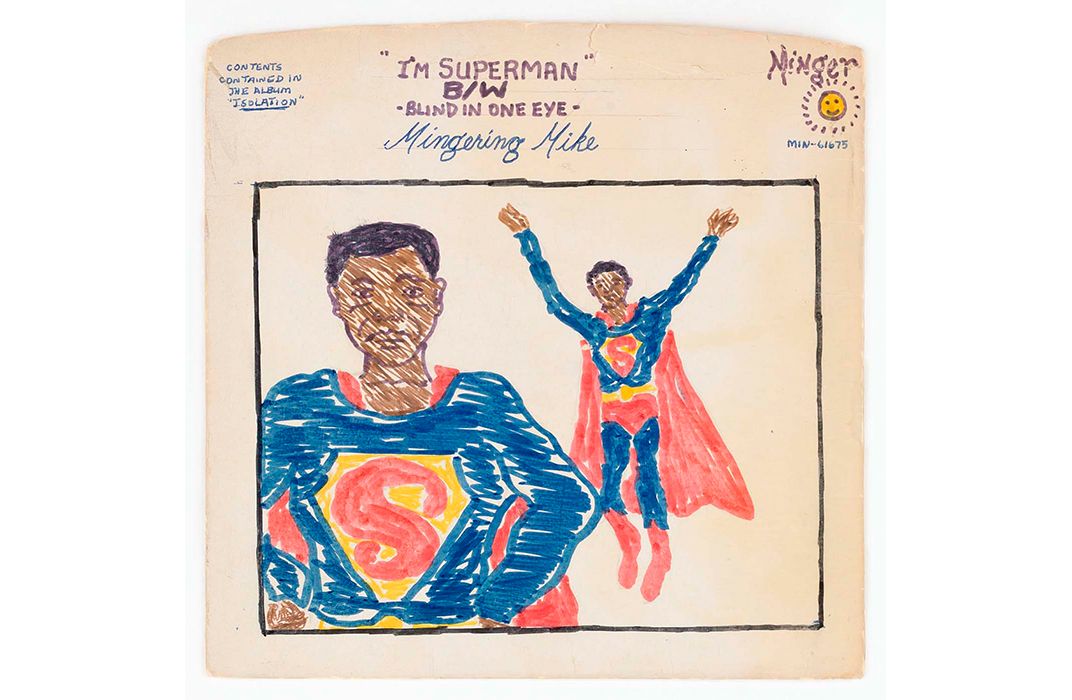

Mike also took on ghetto stereotypes with fake LP covers starring Audio Andre,—a slick, red-suit-wearing sharpie—and the injustice of poverty, with The Drug Store, a fake album sleeve featuring a pastiche of a junkie’s tools—gloves, syringe, matches, a rubber hose to tie off with, and a square of foil holding a mound of white powder. Then there’s Isolation. “This album is dedicated to my dear troubled kin," say the liner notes, "& to anyone else whom once was, but’s not anymore, ‘you can only dig it if you’ve been there.’”

There was also humor. The Exorcist, a phony 45 dates to 1974, the year the Linda Blair horror film was terrifying audiences. It was released on the imagined Evil Records label. Others to follow were: Instrumentals and One Vocal, by the Mingering Mike Singers & Orchestra and Boogie Down at the White House, from 1975, featuring two bell-bottomed, platform-shoe-sporting characters disco-ing on the sidewalk in front of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

“It was just fun being able to have that creativity,” Mike says.

That creativity flowed until 1977, when Mike received a pardon letter in the mail from President Jimmy Carter. He performed community service and got a job. The fantasy world receded as he became an adult in his late 20s, out in the real world. “I started noticing it had been a year when I hadn’t written anything, and then it was like a pressing thought that I’ve got to do it, and then I said, ‘no, when it’s ready it will come out,’” he says.

But by the 1980s, he still hadn’t created much new, and he moved his collection into storage. At some point, Mike couldn’t make the payment on the unit, and the contents got auctioned off.

The creations—and the magical world—were then truly lost to him. But, in 2004, vinyl record collector Dori Hadar stumbled upon a cache of the phony LP covers at a flea market. Hadar was an investigator for a Washington-based defense attorney, but he too, had an escape world. On weekends and holidays, he was a "crate digger," mining thrift stores, flea markets and record shows for obscure LPs to add to his collection.

But the crates he came upon that day in 2004 were full of LPs that he struggled to understand. They were by artists he’d never heard of, and they seemed to be hand-drawn. Maybe they were a school art project. Whatever they were, Hader had to have them, and he paid $2 for each one—a hundred or so. The same day a collector-friend said he’d seen similar strange-looking LPs being sold by the same vendor elsewhere. Eventually, after some cajoling, the seller led the two to a storage unit where more treasures awaited.

Hadar pieced together the evidence at the unit and followed a trail of clues to an address in Maryland, and eventually found Mingering Mike. But Mike did not want to meet with Hadar initially. Hader wanted to give everything back to Mike.

“I was skeptical of it,” Mike recalls, but when Hadar presented a plan to curate and protect the collection, Mike was touched. They became fast friends, bonding over music and collecting. “We're quite an unlikely pair,” says Hadar, now 40. “I'm not sure how our paths ever would have crossed had it not been for his albums popping up at the flea market,” he said.

Instead, Hadar became Mike’s co-conspirator, his manager, his protector, his maven and his friend. “Mike is a really unusual and intriguing guy,” says Hadar. Quiet and reserved, until he assumes the Mingering Mike alter ego, then he throws on a costume, and starts telling jokes.

But, he says, “When I tell him about an exciting development—like someone interested in optioning his life story for a biopic, for example—he usually says, ‘wow, well that sounds pretty good.’”

“It's almost as if he has expected this all along,” Hadar adds.

Mike knows his art touches people, but—despite his youthful ambitions—he’s not seeking fame. “On the one hand he’s very savvy and aware, and on the other he’s completely divorced from that world,” says Trevor Schoonmaker, chief curator at Duke’s Nasher Museum of Art.

Schoonmaker had read about Mike and was intrigued. He included some of Mike’s fake LP covers in a Nasher exhibition in 2010, “The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl.”

That aware/unaware dichotomy—which creates the aura of a childlike introversion and a savant-type mysticism—has drawn many to Mike. During the Duke exhibition, David Byrne, a founder of the pioneering art-rock band the Talking Heads, approached Mike to see if they could make a record together. Byrne is both a visual artist and a musician, and his work was also in “The Record” show at Duke. But, the venture with Mike did not work out for various reasons.

More recently, Peter Buck, a co-founder of the band R.E.M., commissioned Mike to draw the cover for an upcoming solo LP. “He wanted to be a superhero,” says Mike, who obliged Buck’s fantasy.

The Smithsonian “is the perfect place for his work,” says Schoonmaker. “Not only is his work undoubtedly and almost so incredibly American and of a moment and a place and a time, but he’s from D.C. He’s in the backyard of the Smithsonian.”

George Hemphill, a Washington, D.C. gallery owner and collector who has been representing Mike since Hadar brought the two together in 2004, says he, too was captivated by Mike’s uniqueness.

Mike’s detailed universe is like a novel, with character development, plot lines, and plenty of narrative detail, Hemphill said. “The thing that clenched it for me in terms of narrative power was when I saw an album that was not a successful seller and was now being offered at a discounted price,” said Hemphill.

Mike pretended that one of his LPs was not popular, so the dollar figure on the price tag is crossed-out replaced by a hand-written lower dollar figure. Sometimes, Mike painstakingly cut cellophane—complete with the record store’s price tag—off the covers of real LPs he’d bought, and then slipped his fake LPs into those same cellophanes.

Aside from the Peter Buck commission, and some other periodic requests, Mike doesn’t create much anymore. He says he doesn’t feel that urge or drive the way he did when he was a kid. He may still like bringing out his alter ego every once in awhile, but he says he prefers to fly under the radar. “It’s best to be low-key so there are no interruptions or people gathering around me,” he says. He wants to be a regular guy at his job and at home.

The fame he’s had over the last decade “hits me every now and then,” he says. And when something new comes up—like the Smithsonian exhibition—“I don’t react doing yippee and back flips and stuff like that, but it’s really incredible.”

“It’s like Rip Van Winkle goes to sleep and he wakes up 40 years later," he adds, "and everyone’s enjoying and amazed by this person’s talent.”

"Mingering Mike's Supersonic Greatest Hists" is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through August 2, 2015 and includes nearly 150 works of art by the Washington, D.C. artist. The collection was acquired by the museum in 2013.

Mingering Mike

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)