Karl Marx, My Puppy ‘Max,’ Instagram and Me

A historian tries hard to understand modern society and buys a #cutepuppy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/fe/69fef3c5-a1ec-4f48-b923-ccb555b07b0b/npgkarlmarxweb.jpg)

Karl Marx, who was an acute analyst of society, though less successful as a revolutionary prognosticator, wrote one of the most evocative sentences on modern times when he described how under modernity “all that is solid melts into air.”

Marx meant that the instrumental, market relations of capitalism were colonizing all aspects of human life, shredding any distinction between public and private as well as bending “traditional” institutions—marriage, the family, religion and so on—to its omniscient will.

Early on—he wrote in the mid-19th century—Marx recognized that everything could be monetized.

Because he was also a romantic and somewhat sentimental, he realized that personal relationships were disappearing in an ever-expanding market for goods and services. What Marx argued was that traditional institutions and relationships would dissolve—melt into air—paving the way for a new society based on the revolutionary achievements of capitalism and married to a new humanism founded on the abundance created by capitalism. In this scenario he would be disappointed. Marx underestimated the extent to which capitalism would find continual ways to reinvent and reinvigorate itself, not least by continually melting into air and re-emerging in astonishing new forms.

The theoretical model of the modern economy—still taught in the text books of Econ 101—posited the production of goods and services along rational, predictable economic lines. But in reality the actual dealings of trade and the market was shot through with uncertainty and irrationality.

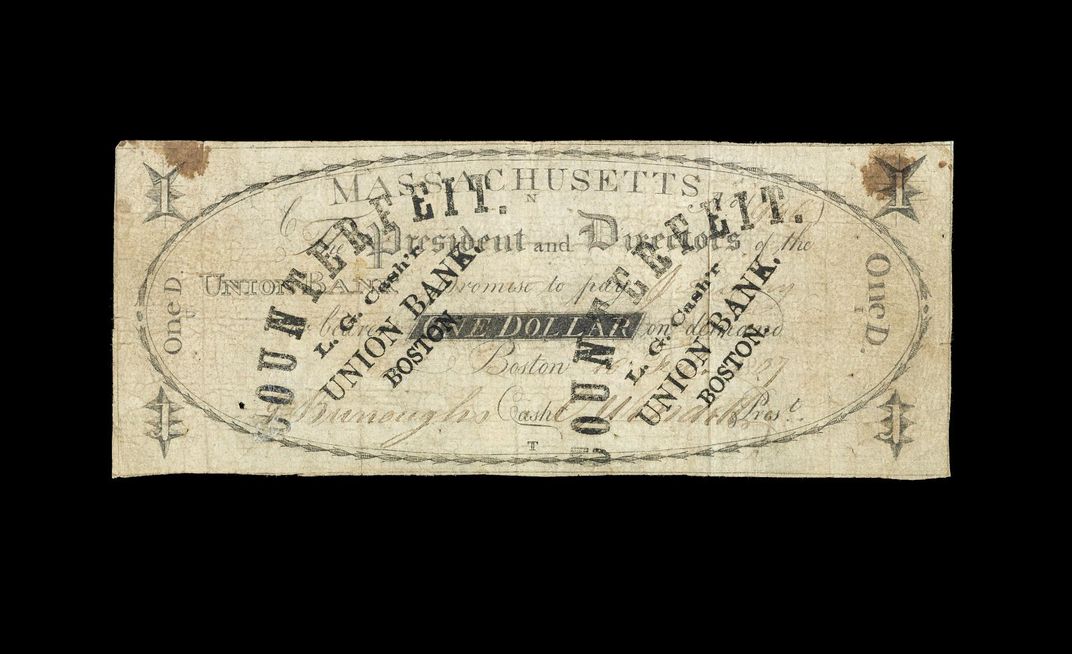

What Marx recognized, but as a hardheaded 19th-century empiricist repressed, was that there was always something mysterious about market relations. Human psychology, in particular the desire to chase the “next big thing” and make a killing, made swindling not just a by-product of the market, but very possibly it’s raison d’etre.

Instead of fulfilling society’s material needs, the market took on a life of its own, fulfilling not needs but the demands for a quick buck. Or a quick guilder as the case may be—consider the “Tulip Mania” in 17th-century Holland, then probably the most advanced economy in the world.

It began with the rational idea of producing flowers for a population that was becoming interested in taste and adornment, not just subsistence, but it quickly metastasized into a speculative bubble. As the price of ever more exotic breeds of tulips rocketed into the stratosphere, along with the renowned “black” tulip, which may or may not have actually existed, the whole edifice collapsed with the over-extension of the credit market and the bankers’ realization that everyone had been walking on air.

Other speculative bubbles have followed regularly, down to the American housing bubble of the early 2000s. Perhaps these free-market catastrophes are just episodic results of the natural exuberance of business and the regular oscillation of expansion and contraction of markets in modern times. But there may be something more systemic at work.

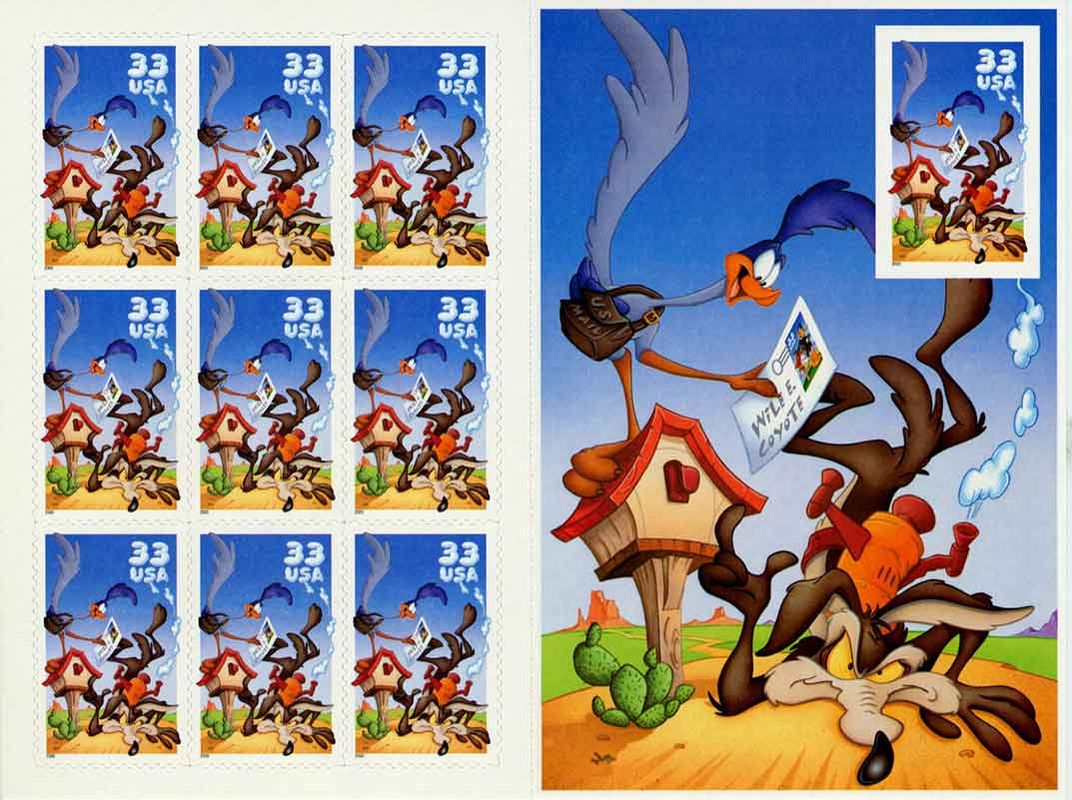

The historian of American counterfeiting, Stephen Mihm, cogently addresses this point in an analysis that points out that it didn’t matter if coins and bills were counterfeit or contained diminished amounts of silver and gold, so long as people maintained the fiction that these symbols of value actually contained real value. Velocity was the important thing: if everyone remained complicit and kept things moving then the system would work. It’s only when, like Wile E. Coyote, people looked down that they realized that there was nothing but air beneath their feet.

The ubiquity and rapid expansion of the internet, and the services provided by it, ranging from retail to human relations—pornography, online dating—would have delighted Marx for adding another dimension to his prophecy (think about how Amazon has destroyed the brick-and-mortar shop) while appalling him because of its evidence of capitalism’s ability to continue to generate new social relations out of its basic business of buying and selling.

With the internet roughly 25 years old, and social media only slightly less so, it is interesting to pause—something the internet doesn’t actually let you do—to assess the ways social media has become a new product and a new way of relating to other people. In particular, the question that troubled Marx is one that should interest (and perhaps trouble) us: Are people just commodities?

And with the appearance of the virtual world, how do we know that anything is an accurate representation of the real world or just carefully crafted “smoke and mirrors”?

Even as a stodgy old historian, I am on social media, shilling my academic wares and delivering selected images or commentary on my life. Or rather, what appears to be my life. It’s hard to tell.

What seems potentially different and new about the Internet is not that it provides an accelerated way to market things, but it vastly expands the opportunity to make money by doing nothing; i.e. the dream of the confidence man and woman.

For instance, I just acquired a puppy and posted pictures of him, which have garnered many “likes” and favorable comments. I’m connecting with my fellow Netzins and the Twitterati. With my dozens of followers, I assume that I will soon be receiving money and dog food from various anonymous corporations that like the style of my posts even though they’ve never met my dog; whose name is Max, by the way.

In his mordant novella, The Confidence Man, set on a Mississippi Steamboat, Herman Melville provided one variant of the confidence man: a shadowy individual who buttonholed his fellow passengers, imploring them to buy shares in the Blue Sky Mines. The poor guy actually had to work hard, going out in the world with his fake stock certificates and a plausible pitch. Now it can all be done virtually—in no-place at all except in cyberspace.

Fraud is inevitable not just with big financial crimes but in smaller, more personal areas in which a connection is promised but is actually vaporous—something like a tenth to a quarter of all on-line dating profiles are fraudulent—shysters hoping to lure lonely hearts to part with their money.

But fraud will always be with us. What is more interesting is how marketing on the Internet, and its various permutations from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram to Pinterest to Snapchat, has become a market not for “things” but for individuals.

Here the revolutionary development is on Instagram, where the images of people—not the people themselves, mind—become monetized to the point that the individual receives money just for simply posting pictures of themselves in a variety of poses and situations.

The Internet, of course, has rapidly expanded the range of celebrity culture but this was still usually tied to an actual thing or product that the “celebrity” had done; movie stars made movies, athletes played sports, musicians dropped tracks. There was an actual product tied to the individual and the larger entity that she or he represented.

But while there have always been people who are famous for being famous, now this is becoming a whole category of privileged worker under the Internet mode of production. The Kardashians are a prime case in point but so are fitness and lingerie models, skateboard kids and sites providing pictures of cute animals.

People, once they achieve a critical mass of “likes” and followers on social media, now get companies or brands to pay them money. For no real reason at all. Meanwhile, the traditional journals, newspapers, magazines and other providers of solid scholarship are struggling to compete in advertising markets that are chasing after the providers of cat videos and Kardashians.

As the wider social connections of the visible world have dissolved and we are thrown back—as Marx also predicted—on the isolated and alienated individual self, that isolated self has become a commodity for sale—a sale whose terms are completely randomized and inexplicable. What Marx didn’t anticipate (how could he? The poor bastard didn’t even have a telephone) was how modern society would end up selling the “air” itself: the image of someone who is apparently real but who has no real life outside of his or her appearance on social media. As the ad says, “Image is everything.”

Like the tulip craze, the current iteration of social media will doubtless fall away to be replaced by something else; Twitter is already declining. It’s inevitable that what we now see as inevitable and necessary parts of the virtual world will disappear to be replaced by something else, a reinvention that, like Wile E. Coyote, keeps us all running on air. Just don’t look down.

In the meantime, I have to go on my social media platforms and post pictures and video of Max, my #cutepuppy.

I don’t actually have a puppy. Or do I? You’ll never know for sure.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)