Ken Burns’ New Series, Based on Newly Discovered Letters, Reveals a New Side of FDR

In “The Roosevelts”, Burns examines the towering but flawed figures who really understood how character defined leadership

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/3d/cb3d30b1-7cb7-44e2-b05e-71a2b6ad3e51/be003491.jpg)

One of the most influential documentary filmmakers working today, Ken Burns has made his reputation by presenting the stories of the American experience with unmatched drama and flair. His topics have ranged from the Brooklyn Bridge to baseball, from Mark Twain to jazz, Prohibition, and the national parks. Remarkably, his works don’t date: As we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, his legendary PBS series on that war remains as relevant today as it first was when it aired to critical acclaim in 1990.

Burns spoke at the National Press Club this week, just as his riveting new seven-part PBS series, "The Roosevelts," premiered. The first episode had aired the night before, and Burns, along with long-time collaborator Geoffrey C. Ward and PBS president and CEO Paula Kerger, were, as Teddy Roosevelt would have said, “dee-lighted” by chart-topping viewer ratings. In an unprecedented move, PBS is streaming the entire series on its website just as it is airing the series in prime time each night this week.

His biographical approach is to look “from the inside out,” and he captures the historic moments of American life with deep dives into personal letters, diaries and newspapers. But it is his use of still photographs that has been most revealing. He calls photographs “the DNA” of everything he does, and his evocative slow-scans have transformed subjects like the Civil War into a cinematic experience. This slow-motion scanning technique is now known as “the Ken Burns effect.”

In "The Roosevelts," Burns focuses on the towering but flawed figures who, before they were “history,” were “family.” He was able to draw on newsreel footage, radio broadcasts and personal documents—notably, a trove of newly-discovered letters between FDR and his cousin Daisy Stuckley—as well as on more than 25,000 still photographs. Ultimately, nearly 2,400 stills were used in this series.

He told the Press Club audience that his objective in this series was to illuminate a very complicated narrative about figures that had often been explored individually, but had never been viewed together “like a Russian novel.” In the years covered by the series, from Theodore’s birth in 1858 to Eleanor’s death in 1962, Burns suggests that their lives intersected with the rise of the American Century, and that they were “as responsible as anyone for the creation of the modern world.”

As a biographer, he felt it “hugely important to understand the world they created by exploring where they came from.” His focus is on both their inner and outer lives, and on illuminating the flaws as well as the strengths woven through their characters. Above all, his goal was to create a nuanced portrait rather than a superficial valentine.

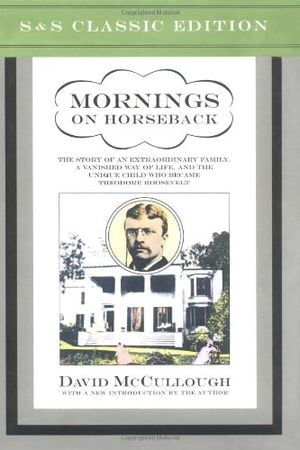

Burns explores how Theodore Roosevelt’s embrace of the motto “Get Action” transformed him from a sickly little boy into an energized force of nature. Describing Theodore in the second episode, historian David McCullough—whose 1981 TR biography, Mornings on Horseback, won a National Book Award—calls him a genius who could read books in gulps and retain essential points for years. But there was a dark side to TR’s family as well, and Burns conveys the depression that lurked within Theodore—how his obsessive physical exertions were in part meant to “outrun the demons.”

As president, TR became a role model for his young cousin Franklin. Where Theodore was always a blurred portrait in motion, Burns depicts FDR as a far different personality. Franklin had a look of “distance in the eyes” that made him more “opaque.” What has allowed the filmmaker to create a more revealing image of FDR in this series is a treasure trove of newly-discovered letters between FDR and his cousin and confidante, Daisy Stuckley. Because he writes her with an unguarded spirit, FDR is here fleshed out more fully than in his better-known public persona.

Eleanor, another cousin in the sprawling Roosevelt bloodline, is introduced along with Theodore and Franklin in what Burns calls the “table setting” of the first episode. Her story emerges more fully as the series proceeds, and why she succeeded in her life at all is what makes her story so fascinating: her beautiful mother was greatly disappointed by her unbeautiful daughter, even calling her “Granny.” Orphaned by the time she was 10, Eleanor gradually discovered that if she could be useful, she could be loved—or at least needed. As Burns told the National Press Club, Eleanor represented “a miracle of the human spirit,” and went on to live such a productive life that she became “the most consequential First Lady in American history.”

According to Burns, the central issue he develops in the series, and the guiding philosophy that connects all three Roosevelts, deals with the relationship between leadership and character: what is the nature of leadership? How does character affect leadership? And how does adversity affect character?

Burns has selected some of America’s greatest actors to bring his subject’s words to life, including the voices of actors Paul Giamatti as Theodore, Edward Herrman as Franklin, and Meryl Streep as Eleanor. Their voices imbue "The Roosevelts" with the kind of immediacy FDR created with his fireside chats, and a relevance that is both recognizable and haunting.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)