The Laptops That Powered the American Revolution

Always on the go, the Founding Fathers waged their war of words from the mahogany mobile devices of their time

:focal(516x209:517x210)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/7f/b17f8384-3223-4988-9e6d-890c16337e3b/finaljeffersonwashingtonhamiltoncollageweb.jpg)

Delegate to the Continental Congress, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, General Washington’s aide-de-camp, secretary of state, president of the United States, secretary of the treasury. During their lifetimes, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton epitomized the role of American Founding Father, all of them heavily involved in the birth of the new United States and the shaping of its government and future.

Between them, they performed some of the most important tasks in forming our nation, but for all three men, their significant contributions came in large part through their writings. The world has known many inspiring revolutionary leaders, but few whose written legacy so inspired the world to embrace a new form of government, and their nation to stay true to the new republic’s founding principles and charter for more than two centuries.

Within the political history collections at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History are three important links to these men and the ideals that inspired them: the portable writing boxes of Jefferson, Washington and Hamilton.

When staff at the Smithsonian recently took the boxes out to be photographed together for the first time, I was lucky enough to witness this moment. We were standing in the presence of the brilliant minds that shaped our country.

Some of us stood in silent admiration. A few even got teary-eyed. America is a nation of ideas, and here were the instruments that first made those ideas a reality and transmitted them to the wider world.

The 18th-century writing box, also known as a dispatch case, portable desk and writing case, would have been an important object for the traveling Founding Father to own. Like the laptops and mobile devices of today, a writing box provided its owner a base from which to communicate, even when on the move.

A box generally contained space for paper, pens, ink and pencils, and often unfolded to reveal some type of writing surface as well. For Jefferson, Washington and Hamilton, who were often required to work away from the fully stocked desks they would have had in their homes and who were constantly writing letters or essays, the ability to travel with a small box with the most essential items from a writing desk was crucial. Each of their boxes, however, while serving similar purposes, is different.

Jefferson’s writing box is small and light, made of a beautiful mahogany with satinwood inlay. The top is a hinged board that can be propped up as a bookstand, or unfolded to twice its size to become a writing surface.

A small drawer provides storage for paper, pens and ink. It is emblematic of his many interests and talents. Jefferson spent more than 40 years designing and redesigning his home Monticello in Virginia, invented a new type of moldboard for a plow, and crafted his own designs for a sundial, a wheel cipher, a polygraph, and more. So it comes as no surprise that his desk was done after his own drawing. Jefferson had the desk constructed by Philadelphia cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph sometime in either 1775 or 1776.

It was on this desk while away from home as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress that he drafted one of the seminal documents of our nation: the Declaration of Independence. Over the next half-century as a diplomat, cabinet member and president, Jefferson continued to write copious amounts, some of it undoubtedly on this very desk.

In 1825, Jefferson sent the desk as a gift to his granddaughter and her husband, Ellen and Joseph Coolidge, with a note in his own hand affixed beneath the writing board attesting that the desk “is the identical one on which he wrote the Declaration of Independence.” In 1880, the United States government officially accepted an offer from the Coolidge family to donate the desk, and it was placed in care of the State Department until 1921, when it was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution.

For seven long years after the Declaration was written, the Revolutionary War raged, and George Washington was fighting at its forefront—and writing. Washington’s dispatch case is of a completely different design than Jefferson’s—more easily portable but without as much space to write on.

It was intended for use by someone constantly traveling. It was intended, in short, for someone like the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. The case is a slight rectangular box made of mahogany and covered with black leather. A hinged lid at the bottom opens to reveal several compartments for writing implements while the top has a leather pocket for stationary and documents. It could easily be slipped into a saddle or travel bag and carried to its owner’s next location.

As Commander-in-Chief, Washington had to be in constant communication with army officials and the Congress, sending dispatches, issuing orders, and writing letters both political and personal. His most pivotal decisions of the war were not issued on the battlefield but from his pen using this very case.

Like the Jefferson writing box, those to whom the case was passed down eventually recognized its significance to the country and it was presented to the government in 1845 by Dr. Richard Blackburn in care of the U.S. Patent Office. In 1883 it was officially transferred to the Smithsonian, the first of the three boxes to arrive.

For a man whose legacy exists most prominently in the volumes of writings he produced during his lifetime, the sturdy workhorse quality of Alexander Hamilton’s portable desk seems fitting. Throughout his lifetime, Hamilton kept up a continuous stream of correspondence, military papers, cabinet papers, Treasury records and political commentary. Most famously he authored 51 of the 85 essays of The Federalist Papers in just eight months. Hamilton knew the power of the written word and strove to use it to its fullest.

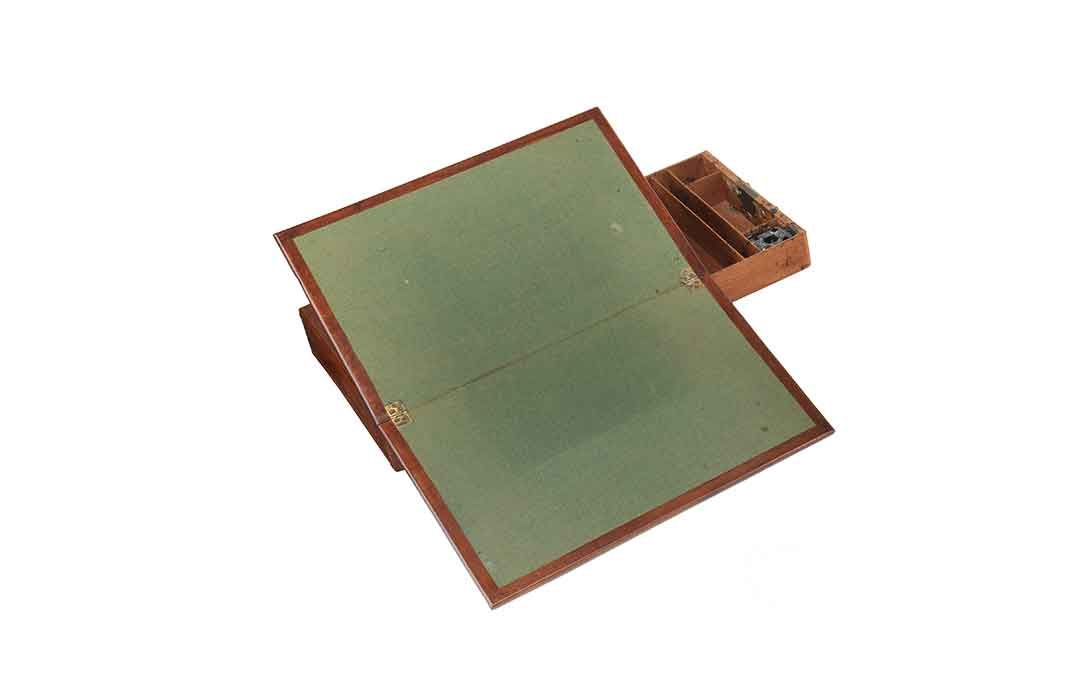

The thick mahogany travel desk that resides in the museum's collections is just the type to stand up to such constant use. It unfolds in the center to provide a large, slanted writing surface and includes a side drawer and slots for writing instruments. Like that of his political rival, Jefferson, Hamilton’s writing box remained with his descendants until they presented it to the Smithsonian in 1916.

"Politics as well as Religion has its superstitions. These, gaining strength with time, may, one day, give imaginary value to this relic, for its association with the birth of the Great Charter of our Independence,” wrote Jefferson in the affidavit he attached to his writing box.

Time has proven Jefferson right, not only about his own box, but about those of Washington and Hamilton as well. Together, these objects that began as ordinary instruments remind us that our nation was built on a foundation of inspiring words, a new social contract Americans continue to honor, and endeavor to fulfill.

With these desks history was written, and with these desks our nation took shape. It is fitting that they all found their way to our national museum in the nation’s capital, the city where ultimately Jefferson, Washington and Hamilton came together during Washington’s tenure as president and worked, fought, compromised—and wrote—in the struggle to establish a nation.

This war of words that has been passed down over 200 years—more than the muskets and cannons fired during the Revolution—ensured that our new country would not only succeed, but flourish.

Bethanee Bemis is a museum specialist in the political history division at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. She wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Bemis_Bethanee_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Bemis_Bethanee_2.jpg)