The Lasting Riddles of Orson Welles’ Revolutionary Film ‘Citizen Kane’

This year’s award-winning “Mank” attracts new attention to the 80-year-old American classic; two Smithsonian curators share insights

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/84/4084bee2-cfeb-41ea-8dfb-9714cf819881/untitled-2.jpg)

The sign clearly says “No Trespassing,” but the camera moves beyond it, taking the audience forward toward a castle to become voyeurs at the deathbed of a once-powerful, often-lonely man. “Rosebud,” Charles Foster Kane says with his last breath—and a mystery begins to unfold. Disoriented viewers immediately find themselves watching a newsreel that tries and fails to sum up the man’s life. A discouraged editor sends a reporter on a quest to discover the meaning of Kane’s last words.

When the film debuted 80 years ago this month, Citizen Kane was not a hit, but today, it is considered to be among the finest films ever made. Its experimentation with light and sound effects was revolutionary, but it won only one Oscar—for screenwriting. Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles shared that honor after an unusual writing collaboration now portrayed in Mank the 2021 award-winning film by David Fincher. Welles, 25, had also produced, directed and starred in the film.

Read more about the enigmatic sled in Citizen Kane

“Trends in film criticism come and go. That’s why it’s just so interesting that this single film has been identified time and time again by critics all over the world as the great American film, or even the greatest film of all time,” says the Smithsonian’s curator of entertainment Ryan Lintelman at the National Museum of American History.

Lintelman credits the Hollywood studio system and its industrialization of filmmaking with playing a big role in the film’s success. “A film like Citizen Kane couldn’t be made without having all that machinery,” he says. The film’s poor Academy Award showing “is really a reminder that the Oscars capture a moment in time more than they capture the eternity of cinema history.”

Citizen Kane, told in a series of flashbacks drawn from the minds of the people closest to the newspaper publisher, follows the reporter seeking in vain to find the meaning of "Rosebud." The audience’s discovery in the last scene that Rosebud was the name of the sled Kane owned in early childhood “is not the answer,” wrote critic Roger Ebert. “It explains what Rosebud is, but not what Rosebud means. The film’s construction shows how our lives, after we are gone, survive only in the memories of others, and those memories butt up against the walls we erect and the roles we play. There is the Kane who made shadow figures with his fingers, and the Kane who hated the traction trust; the Kane who chose his mistress over his marriage and political career, the Kane who entertained millions, the Kane who died alone.”

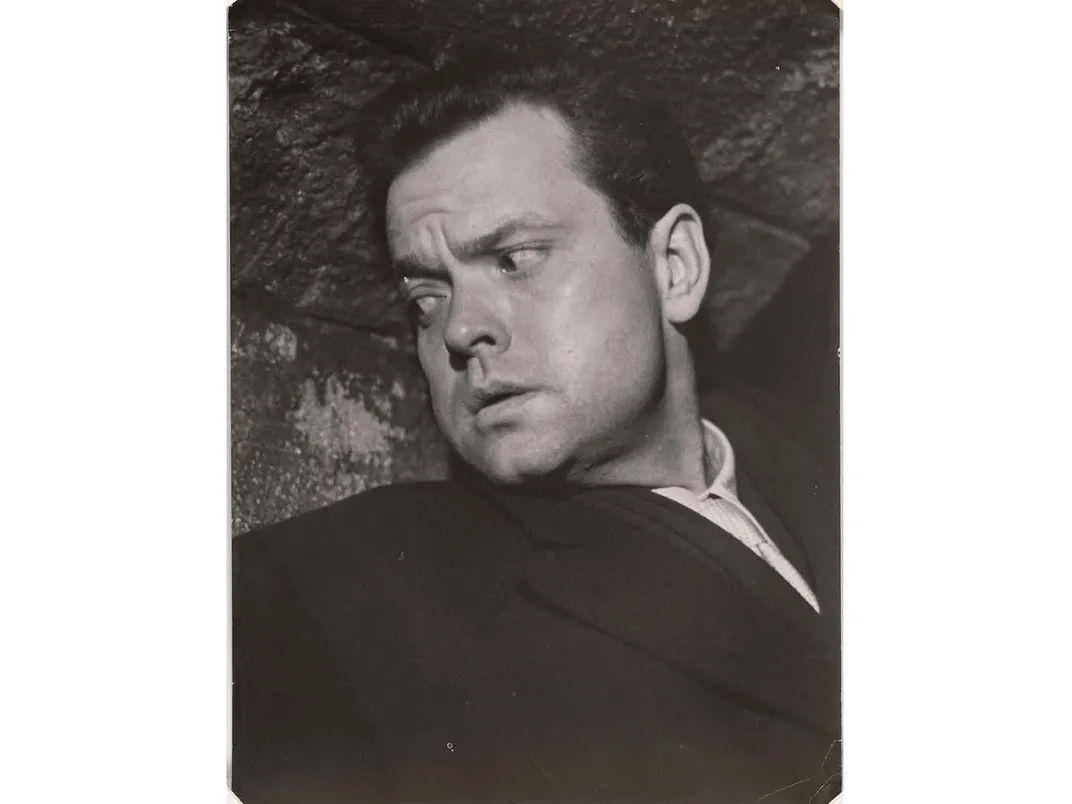

Welles, who lost his parents at a young age, was a wunderkind, a child prodigy. “There just seemed to be no limit as to what I could do. Everybody told me from the time I was old enough to hear that I was absolutely marvelous,” he said in a 1982 interview. “I never heard a discouraging word for years. I didn’t know what was ahead of me.” When he was only 23, Time magazine put him on the cover, calling him the “brightest moon that has risen over Broadway in years. Welles should feel at home in the sky, for the sky is the only limit his ambitions recognize.”

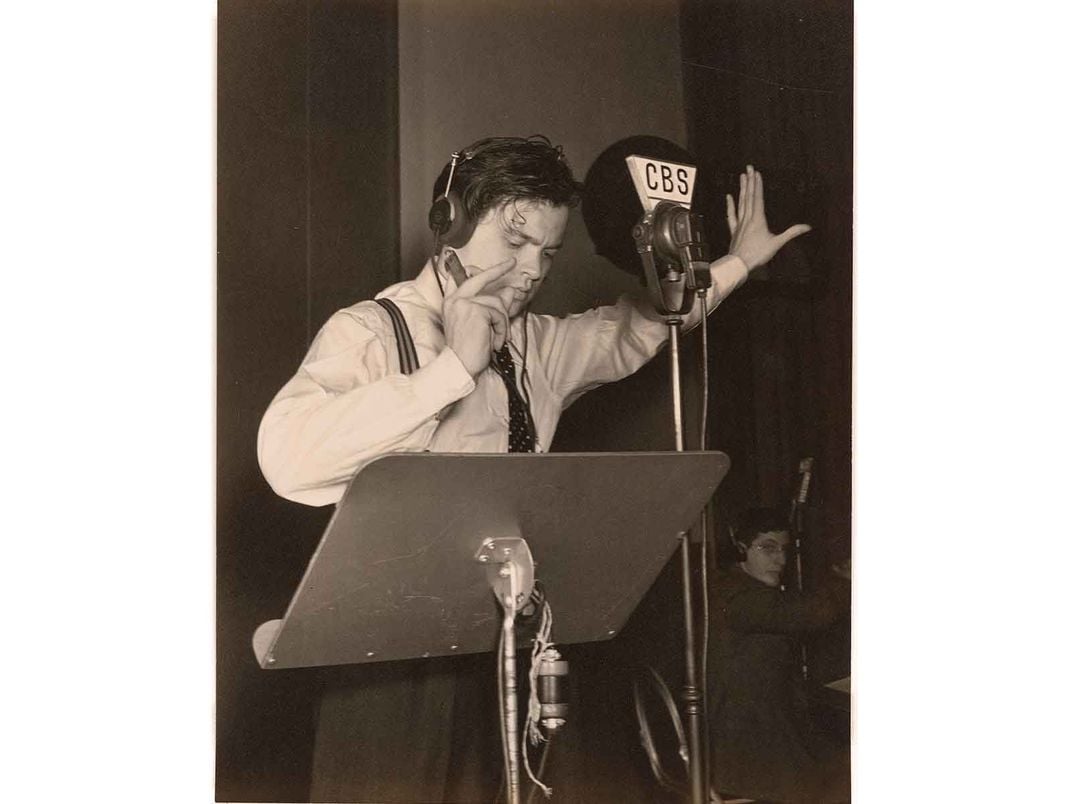

A great deal of enthusiasm greeted Citizen Kane’s release on May 1, 1941. Welles had made a big splash in staging productions in New York. He directed an all-black cast in a presentation of Macbeth imagined to be occurring in Haiti, and he presented a version of Julius Caesar against the backdrop of Nazi Germany. He also staged a radio sensation with an update of H.G. Wells’ novel War of the Worlds, a performance so credibly reenacted that many listeners panicked, believing that Martians had in fact landed in New Jersey. These successes had positioned him with incredible freedom to produce his first film in Hollywood and set his own course.

However, obstacles awaited him. As the film Mank suggests, Mankiewicz laid the groundwork for a hostile reception to the film. He advanced that the film was a thinly veiled bio of William Randolph Hearst, sharing a copy of the script with one of Hearst’s associates.

“Welles really didn’t intend for this to be targeting Hearst in the way that it’s remembered,” Lintelman says. “Americans tend to lionize these people, whether it’s Thomas Edison or Henry Ford or Donald Trump. A lot of times it’s this worship of power and wealth that is sort of out of tune with . . . the idea of a commonwealth that we have.” Lintelman believes the title character was “a compilation, a conglomerate of all these figures throughout American history that have been corrupted by power and wealth in that same way.”

Early in his career, Welles had profited from controversy. As he approached this film and realized that many would assume that Kane was entirely based on Hearst, he did not worry. “Welles thought that the controversy that would stem from this could only be beneficial, and it turned out to be otherwise, terribly so, terribly so, horribly so, big mistake,” says writer Richard France, an expert on Welles’ work.

Hearst responded forcefully to the idea that the film was an attack on him and his lover, actress Marion Davies. He considered buying up all of the copies and pressured theaters not to present it if they expected to be able to advertise in Hearst’s newspapers again. His influence was significant: One in five Americans read a Hearst newspaper every week. No Hearst newspaper reviewed or advertised the film. A group of movie industry leaders even tried to buy the film’s negative and block its release to protect Hearst. Welles avoided that fate by asserting that failing to release the film would be a violation of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. The movie was released, but with all of Hearst’s efforts combined to minimize the impact, Citizen Kane did not generate big box office sales or capture the American imagination.

To view the film strictly as a William Randolph Hearst biography turns out to be most unfair to Davies. In the film, Kane’s second wife, Susan Alexander, is portrayed as an untalented opera singer, whose career becomes an obsession for him. Davies had real talent.

She, in fact, left behind an “incredible body of work,” Lintelman says. “From what I know about Marion Davies, no one in Hollywood had a bad word to say about her.” However, many assumed the film’s often-drunk opera singer was modeled after her. Like Kane did, Hearst tried to manage Davies’ career, restricting her performances and ruling out roles that required her to kiss a costar on the lips. He promoted her work heavily in his newspapers.

“They made Susan Alexander into a tormented, unhappy creature who walks out on her supposed benefactor—this in contrast to the Hearst-Davies relationship, which was generally happy,” wrote Welles biographer James Naremore.

There has been some dispute about Welles’ role in writing the script. In 1971, the preeminent critic Pauline Kael argued in her two-part New Yorker essay “Raising Kane” that Welles did not deserve credit for screenwriting; however, others, including some at the New Yorker, have since disagreed.

Lintelman says, “The historical consensus that we’ve all settled on makes a lot of sense—that it was a germ of an idea that came from Welles that Mankiewicz really fleshed out, and then Welles refined. They are equally credited appropriately in the film in its final release with being co-authors of it.”

The film found its most enthusiastic audience in post-World War II France, where future filmmakers, such as François Truffaut, saw it while a student in a class on experimental cinematic skills. After years of receiving little attention in the United States, the film was re-released in May 1956 and began appearing on television at around the same time. In 1962, it climbed to the top of Sight & Sound magazine’s film critics’ poll, and over time mostly held on to that ranking, while also topping other polls. Today, Charles Foster Kane is much better remembered than the real William Randolph Hearst.

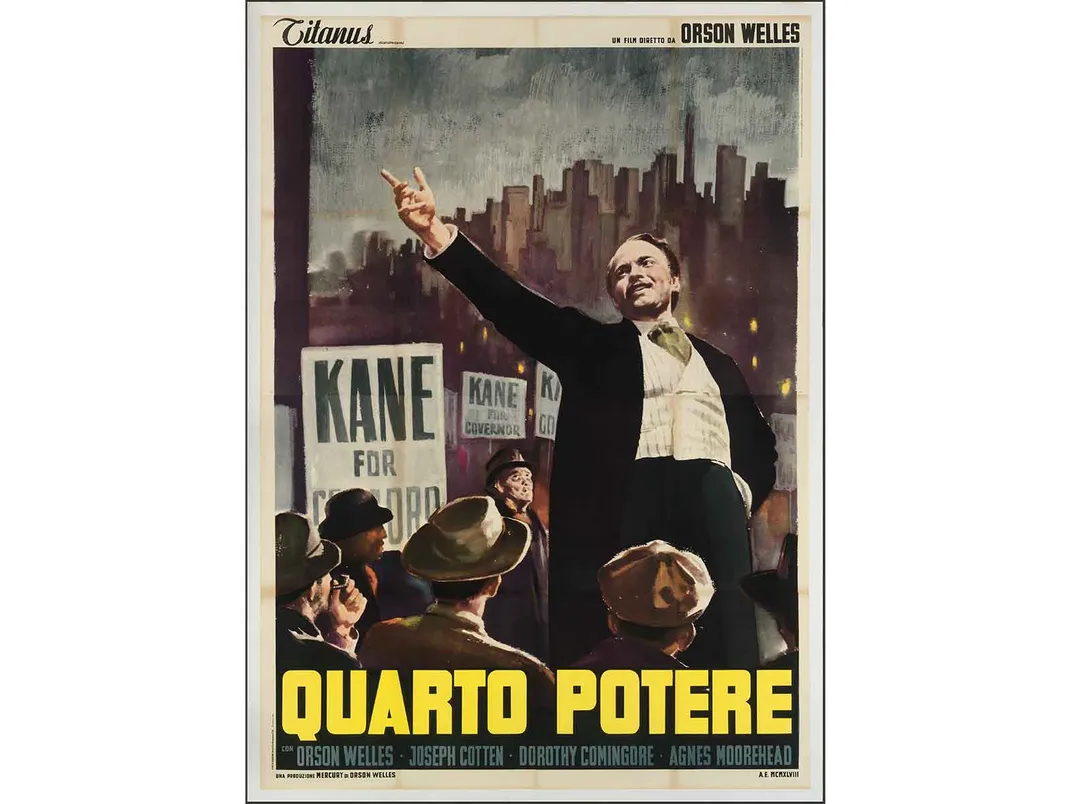

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery holds an Italian poster promoting the film. The movie was not a hit in Italy, which was recovering from its years under the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini when the film debuted there in 1948. The poster, says curator Robyn Asleson, totally recast the film and its message. The title of the film was changed to Il Quarto Potere—The Fourth Estate—and moved the focus away from Kane’s personal life to his newspaper career. An artist produced the poster by combining three images: Two reproduce consecutive scenes from the film, with New York City’s skyscrapers looming in the background. The foreground shows Kane campaigning for governor. “He looks like a demagogue, talking to this crowd with the New York skyline,” says Asleson.

Because stylization was associated with Fascists, Italian moviegoers didn’t like the boundary-breaking film. “It was just not plain enough for them. It was too fancy,” Asleson says, and that affected perceptions of the filmmaker. “And so, they thought that Orson Welles is this kind of very right-wing guy. And in America, he was this very left-wing guy.” (Hearst’s efforts to hurt Welles even led the FBI to open and maintain a file on him because of alleged ties to the Communist Party.) Ironically, Welles was living in Italy at that time, and he was seen as a kind of ugly American married to Rita Hayworth.

Many observers have concluded that Welles’ career went downhill after Citizen Kane. In fact, throughout his career, Welles took less prestigious jobs, such as bit parts on the radio in the 1930s and TV commercials later in his life, to pay for the work he truly wanted to do. Lintelman says, “I’m a big Orson Welles fan. Some of my favorites of his films are Touch of Evil and F is for Fake. So, those folks who do say that this was a career killer for him, they should explore some of those other films because he really continued to be very innovative and interesting.”

Lintelman is disappointed that other than the Portrait Gallery’s poster, the Smithsonian has no memorabilia from the film to display alongside Dorothy’s ruby slippers from the 1939 The Wizard of Oz. He says, “If anyone reading this article," he says, “has any Citizen Kane costumes or props, send them to the museum—please.”

Editor's Note 5/2/2021: A previous version of this article incorrectly indentified William Randolph Hearst's middle name.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)