Lee Ufan’s Transformative Sculptures Are in Dialogue With the Spaces They Inhabit

For the first time in the Hirshhorn Museum’s history, the 4.3-acre outdoor gallery is devoted to a single artist

:focal(1097x388:1098x389)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/38/9338de26-f6f5-4195-b01c-fd715bb69d38/lee-ufan005.jpg)

When the Korean artist Lee Ufan was first commissioned to do a site-specific exhibition in the plaza of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden two years ago, he came to Washington, D.C. see what he would be dealing with.

The museum, itself designed as a “large piece of functional sculpture” by the renowned architect Gordon Bunshaft in the 1960s, is centered on a large 4.3-acre plaza on the National Mall. There surrounding the cylindrical building, works of art are displayed outdoors and year-round in the quiet recesses and grassy nooks of the walled plaza.

Now for the first time in the Hirshhorn’s 44-year history, curators have relocated or stored the artworks on the museum’s plaza and devoted the space, almost in its entirety, to a single artist.

Lee, 83, a leading voice of Japan’s avant-garde Mono-ha movement, meaning “School of Things,” has exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2007, the Guggenheim Museum in 2011 and the Palace of Versailles in 2014. But the artist who is a painter, sculptor, poet and writer, as well as part philosopher, sees his contributions as the finishing of a dialogue begun by the spaces in which he works. “By limiting one’s self to the minimum,” he has written, “one allows the maximum interaction with the world.”

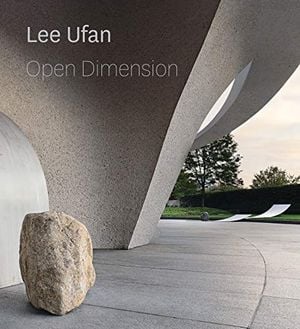

Lee Ufan: Open Dimension

In fall 2019, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden debuted 10 new specially commissioned outdoor sculptures from celebrated Korean artist Lee Ufan. This book accompanies the expansive installation, which features sculptures from the artist's signature and continuing "Relatum" series and marks the first exhibition of Lee's work in the nation's capital.

To create his distinctive, sleek sculptures, the artist brought tons of rock and steel to Washington D.C. But as he said while walking around the ten creations a week before the opening of his exhibition, “Not important, object. Space is more important.”

So in front of a piece on the plaza’s southeast corner with a nearly 20-foot-high vertical silver needle, a steel circle on the ground and two large stones in a field of white gravel that replaces the museum’s grass, the artist explains, because “tension is what I needed.” That helped define the space “because of this gravel and steel, my choice.”

Like every one of his sculptures, it has the title Relatum, to refer to the relations of objects to their surroundings, to each other, and to the viewer. Each work in the series also has a subtitle, and this one, Horizontal and Vertical, refers to the gleaming needle. The piece is now standing at the point where the soaring aluminum tubes and stainless-steel wires of Kenneth Snelson’s Needle Tower long reigned.

Lee’s work is just as defining of the space, while it also echoes the strong vertical of an industrial crane that happens to soar over the National Air and Space Museum, which is undergoing a major renovation across 7th Street. The artist waves this off as a coincidence.

“A plain, natural stone, a steel plate . . . and existing space are arranged in a simple, organic fashion,” Lee once wrote. “Through my planning and the dynamic relationships between these elements, a scene is created in which opposition and acceptance are intertwined.”

The Hirshhorn exhibition, “Open Dimension,” curated by Anne Reeve, is Lee’s largest outdoor sculpture installation of new work in the U.S. It is accompanied by a complementary installation on the museum's third floor of four of Lee’s Dialogue paintings from the past four years, where clouds of color float on white or untreated canvas.

Lee’s takeover required moving or storing familiar plaza sculptures. Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin was transferred to the museum’s sculpture garden across the street; and Roy Lichtenstein’s Brushstroke is on loan to the Kennedy Center’s new performance spaces known as The REACH, but Jimmie Dunham’s sculpture Still Life with Spirit and Xitle, installed in 2016, remains. The work mirrors Lee’s with its use of stone—a nine-ton volcanic boulder (with a smile on its face) crushes a 1992 Chrysler Spirit.

Lee’s work is more sleek. With his Relatum—Open Corner elegantly reflecting the curves in the alcoves of Bunshaft’s Brutalist building; his Relatum—Step by Step has the step climbing a couple of stairs with curling stainless steel.

In another alcove, a shiny piece of stainless steel on its edge curls inward, allowing a visitor to enter and be alone in the center swirl. “It’s kind of like a hall of mirrors,” Lee says to me through a translator. “You’re going to get a little bit disoriented.” Is it meant to be one of those big, rusting spirals by Richard Serra that similarly swallow viewers?

“Not same idea,” Lee says. “Big difference for me.” But, he adds, “Serra is very old friend. First time I met him was in 1970 in Tokyo. He and I were in the same gallery in Germany.”

The works with white gravel especially suggest the quiet grace of a Japanese rock garden, other works with stainless steel bases are placed on the grass, which continue to be watered in the dry autumn. “It’s a problem,” he says. Rivulets from a sprinkler on Relatum—Position, later turned to orange stains in the late afternoon sun.

He plays with the sun and shadow in a two-rock piece called Relatum—Dialogue, in which two boulders placed near one another have their morning shadows painted black on the white gravel (causing two different shadows most of the day, aside from the one moment when they align).

Despite the title, one rock seems to be turning away. “It’s supposed to be a dialogue,” Lee says, “but his mind is different.” Asked if he was trying to depict the kind of ideological division familiar in Washington D.C. within sight of the U.S. Capitol, Lee just laughs.

Some of the work did reflect the city, however. Lee says he admires Washington’s clean layout, compared to the bustle of New York City. “Here, very quiet, very smooth, very slow,” Lee says. “New York is a big difference.” So, Lee created his own pool, a square with two rocks, four sheets of shiny stainless steel and water called Relatum—Box Garden, with only the wind creating ripples on its still, reflecting surface. The work is placed between the Jefferson Drive entrance from the Sculpture Garden and the Bunshaft-created fountain, now working again following two years of repair work.

The centerpiece of the plaza is the fountain, which is also a main focus of Lee’s exhibition. Eleven curved steel pieces—mirrored on one side, are placed in a kind of maze, allowing for two entrances. Once in, a viewer can see how the addition of black ink to the water better reflects the blue sky and the curves of the building above (though the coloring gives a greenish tint to the water spouting at the center of the fountain).

Lee was vexed by the heavy concrete boxes in some of the sculpture spaces that were originally meant to hold landscaping lights, though one of these didn’t seem to infringe much on the steel circles and stone placements in Relatum—Ring and Stone.

The museum wants to keep visitors off the white gravel, though they can approach the works on the grass. Signs all over ask that visitors not touch or climb on the art works—even though Lee subtitles the work Come In.

Lee says the many annual visitors of the Hirshhorn—numbering 880,000 last year—needn’t have a deep understanding of conceptual art to get something out of it. “Experience is more important; not meaning,” he says. “My work has some meaning, but more important is pure experience.” Just then, a passerby noticing the artist stopped him in the plaza. “We wanted to tell you how beautiful it is,” she said.

“Lee Ufan: Open Dimension” continues through September 12, 2020 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)