In the late afternoon of Monday, February 1, 1960, four young black men entered the F. W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina. The weather had been warm recently but had dropped back into the mid-50s, and the four North Carolina A&T students were comfortable in their coats and ties in the cool brisk air as they stepped across the threshold of the department store. Like many times before, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond and Jibreel Khazan browsed the store’s offerings and stepped to the cashier to buy the everyday things they needed—toothpaste, a notebook, a hairbrush. Five and dime stores like Woolworth's had just about everything and everyone shopped there, so in many ways this trip was not unique. They stuffed the receipts into their jacket pockets, and with racing hearts turned to their purpose.

They had stayed up most of Sunday night talking, but as they walked toward the social centerpiece of the Woolworth's store, its ubiquitous lunch counter, fatigue was replaced by the rush of adrenaline. Khazan says he tried to regulate his breathing as he felt his temperature increase; his shirt collar and his skinny, striped tie stiffen around his neck.

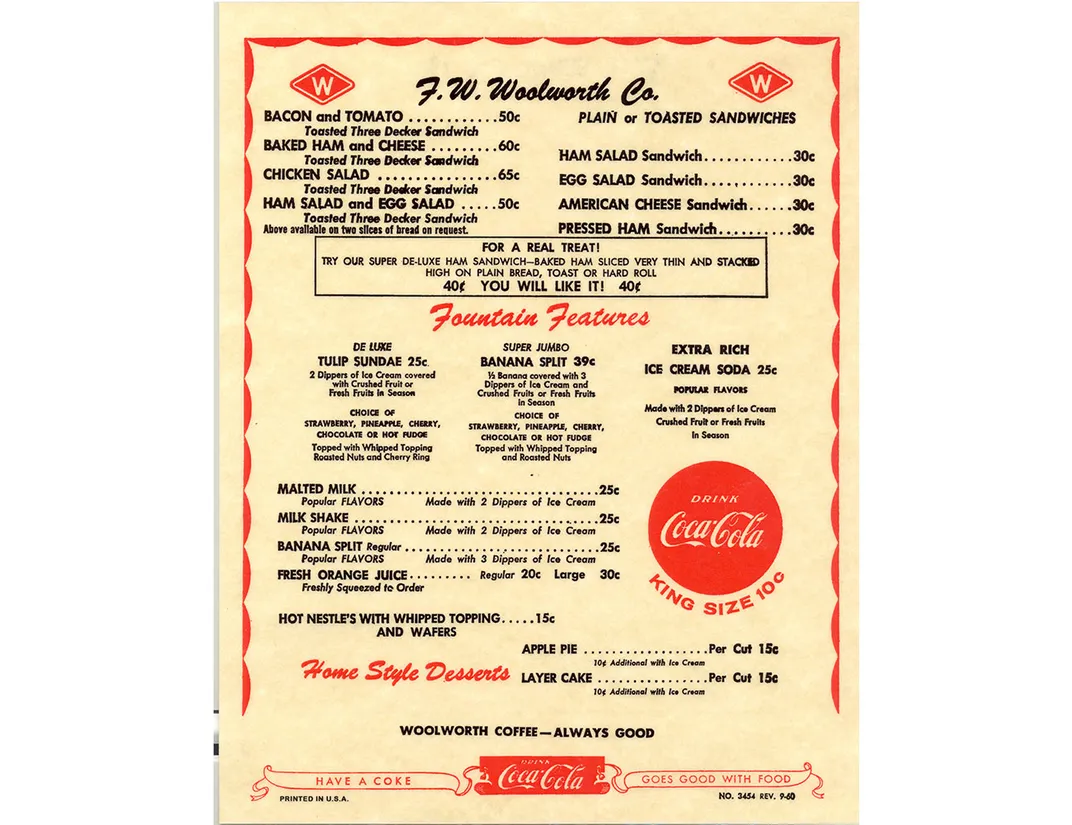

They could smell the familiar aroma of ham or egg salad sandwiches. They could hear the whirr of the soda fountain and its milkshakes and ice cream sodas above the low chatter of diners relaxing over an afternoon cup of coffee or a slice of apple pie. In addition to the sounds and smells of the lunch counter, the four freshmen college students could also sense something else as they looked at one another and silently agreed to walk forward. The friends could feel the invisible line of separation between the shopping area open to everyone and the dining area that barred blacks from taking a seat. They knew, as all blacks in the South did, that stepping over that line might get them arrested, beaten or even killed.

The four were all the same age that the young Emmett Till would have been had he not been brutally tortured and murdered that Mississippi summer five years earlier. McCain and McNeil, motivated by the anger from the years of humiliation they had experienced, looked at one another, then at the counter. All four then moved forward in silence together and sat.

It took a few moments for anyone to notice, but the change within the freshmen was immediate. The Greensboro Four, as they would come to be known, had not embarked on a deep study of Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of satyagraha, his method of nonviolent action, but they experienced the first change it intended to create—a change that takes place within the people taking action. Just as the African American community of Montgomery, Alabama, following Rosa Parks’ arrest in 1955, discovered their power, the Greensboro Four experienced a transformative strength.

McCain, who died in 2014 at the age of 73, has spoken about how he had been so dispirited and traumatized living under segregation that he felt suicidal as a teenager. He often told of how the experience of sitting down in the simple chrome stool with its vinyl seat immediately transfigured him. “Almost instantaneously, after sitting down on a simple, dumb stool, I felt so relieved. I felt so clean, and I felt as though I had gained a little bit of my manhood by that simple act,” he told me when I spoke to him in 2010.

The four students politely asked for service and were refused. The white waiter suggested they go to the “stand-up counter” and take their order to go, which was the policy for black customers. The activists begged to differ as they pulled out their receipts and told her they disagreed with her. “You do serve us here, you’ve served us already, and we can prove it. We’ve got receipts. We bought all these things here and we just want to be served,” McCain remembered saying.

By now there was no sound in the dining area. The voices of patrons were hushed with just the clink of silverware audible as the four sat in silence. “It was more like a church service” than a five-and-dime store, according to McCain. An older black Woolworth's employee, probably worried about her job or maybe their safety, came out of the kitchen and suggested the students should follow the rules. The four had discussed night after night in their dorm rooms their mistrust of anyone over 18 years old. “They’ve had a lifetime to do something,” McCain remembered, but he and his close friends felt they had seen little change, so they were indifferent to the reprimand and suggestion not to cause any trouble. Next, the store manager, Clarence “Curly” Harris came over and beseeched the students to rethink their actions before they got into trouble. Still, they remained in their seats.

Eventually, a police officer entered the store and spoke with Harris. When he walked behind the four students and took out his Billy club, McCain recalled thinking: “This is it.” The cop paced back and forth behind the activists, hitting his night stick against his hand. “That was unsettling,” McNeil told me, but the four sat still and the threat elicited no response. After he had paced back and forth without saying a word or escalating the situation, the activists began to understand the power they could find in nonviolence as they realized the officer didn’t know what to do, and soon left.

The last person to approach the Greensboro Four on that first day was an elderly white lady, who rose from her seat in the counter area and walked over toward McCain. She sat down next to him and looked at the four students and told them she was disappointed in them. McCain, in his Air Force ROTC uniform was ready to defend his actions, but remained calm and asked the woman: “Ma’am, why are you disappointed in us for asking to be served like everyone else?” McCain recalled the woman looking at them, putting her hand on Joe McNeil’s shoulder and saying, “I’m disappointed it took you so long to do this.”

There was no stopping the sit-in now.

By simply taking a seat at the counter, asking to be served, and continuing to sit peacefully and quietly, the Greensboro Four had paralyzed the store, its staff, its patrons and the police for hours that Monday afternoon. None of them expected to freely walk out of Woolworth's that day. It seemed much more likely they’d be carted off to jail or possibly carried out in a pine box, but when a flummoxed Harris announced that the store would close early and the young men got up to leave, they felt victorious. “People take on religion to try to get that feeling,” McCain said.

The action of the Greensboro Four on February 1 was an incredible act of courage, but it wasn’t unique. There had been previous sit-ins. In 1957, for instance, seven African Americans staged one at the segregated Royal Ice Cream Parlor in Durham, North Carolina. What made Greensboro different was how it grew from a courageous moment to a revolutionary movement. The combination of organic and planned ingredients came together to create an unprecedented youth activism that changed the direction of the Civil Rights Movement and the nation itself. The results of this complex and artful recipe are difficult to faithfully replicate. Besides the initial, somewhat spontaneous February 1 act of courage, more components were needed.

One essential ingredient was publicity. Only one photograph was taken of the activists from the first day at Woolworth's, but that was enough to gain some exposure in the press. The Greensboro Four went back to campus in the hopes of drumming up support to continue and expand their demonstration and as word spread it started to swell. “We started growing,” Joseph McNeil says in a video presentation made for the museum by the History Channel in 2017. “The first day, four. The second day probably 16 or 20. It was organic. Mind of its own.”

By February 4, the campaign had grown to hundreds of students. Students from A & T, Bennett College and Dudley High School joined the movement, as well as a few white students from the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina (now University of North Carolina at Greensboro). Within a few days, press coverage had spread and was firing the imaginations of students across the country. Future movement leader Julian Bond often said that, “the Civil Rights Movement for me began on February 4, 1960.” In 2010, I heard him recount how he was sitting with a friend in Atlanta where Bond attended Morehouse College and he saw in the paper a headline that read “Greensboro students sit-in for third day.” Bond wondered aloud to his friend: “I wonder if anyone will do that here.” When his friend replied that he was sure someone would do it, Bond paused and responded: “Why don’t we make that ‘someone.’ us?” Coverage grew and with it, so did activism. By the second week of sit-ins, the burgeoning movement was getting headlines in the New York Times and thousands of students in dozens of cities were roused into action.

Instrumental in the growth of the action of the Greensboro Four and the students who joined them at Woolworth's in early February 1960 was the strategy and planning that occurred more than a year earlier and 400 miles away in Nashville, Tennessee. Unrelated actions like this turned it into a national movement with thousands of students all across the country.

In 1957 Martin Luther King met the 29-year-old theology graduate student James Lawson at Oberlin College in Ohio. Over the previous decade, Lawson had dedicated himself to studying social movements around the globe from the African National Congress in South Africa to Gandhi’s work in India. As a Methodist missionary, Lawson traveled to India and decided then that he “knew that Gandhi’s nonviolence was exactly what we needed for finding ways to strategically resist injustice and oppression.” King urged Lawson to move to the South because “we don’t have anyone like you down there.” And by the next year Lawson took a ministerial position in Nashville, Tennessee, and began taking divinity classes at Vanderbilt University. By January 1959, Lawson and another minister Kelly Miller Smith decided to launch a nonviolent campaign to attack segregation and economic oppression in downtown Nashville.

“Every downtown in the southern part of the country, but also places like Los Angeles, where I live now, and Chicago, were extremely hostile places to black people,” Lawson says. On the one hand there were the signs and the policies that stigmatized African Americans. Blacks not only couldn’t sit at lunch counters, but they couldn’t try on shoes or hats as they shopped in many stores. More important to Lawson was attacking the “prohibition against employment, which was the most torturous aspect of racism and Jim Crow,” he says. Job opportunities were extremely limited for blacks downtown. Company rules or hiring practices meant blacks couldn’t be in most visible positions or often fill anything but menial jobs. “You cannot work as a clerk, you cannot work as a sales person, you cannot work as a department head in a department store,” Lawson says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/06/16063c51-b65d-4769-819e-b24ad1e18175/woolworth-four-19601.jpg)

Wikimedia Commons

Lawson and Smith started looking for recruits to create social change and looked to motivate young people to join them. Lawson says he believes that “young people have the physical energy and the idealism that they ought to always be at the forefront of real change and they ought not be disregarded like so often is the case.” Two of the most important students to join Lawson and Smith’s weekly classes on nonviolent action were Diane Nash and John Lewis. The Nashville group created their strategy and planned for action following the steps and principles set forth by Gandhi.

They conducted test sit-ins in downtown Nashville during the fall of 1959 as part of the investigative phase of their planning—they sat down and violated the segregation policy. Nash said she was surprised and overjoyed when she heard that the Greensboro Four had taken action. Because of her group’s unrelated strategizing and planning, they were able to quickly respond and organize sit-ins of their own in Nashville beginning on February 13. ”Greensboro became the message,” Lewis says in the film. “If they can do it in Greensboro, we too can do it.” By March, the activism had spread like wildfire to 55 cities in 13 states.

The campaign grew and transformed into a general movement organized and driven by students in large part through the leadership of Ella Baker. Historian Cornell West has suggested: “There is no Civil Rights Movement without Ella Baker.” Baker was born in December 1903 in Norfolk, Virginia. As a young girl she was influenced greatly by the stories of her grandmother who resisted and survived slavery. After graduating from Shaw University in Raleigh, Baker moved to New York and began working for social activist organizations from the Young Negroes Cooperative League, to the NAACP, to In Friendship, an organization she founded to raise money to fight Jim Crow in South. In 1957 she moved to Atlanta to help lead Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). When the student sit-ins started in 1960, however, she left SCLC to organize a conference to unite student activists from across the country. The April 1960 meeting at Shaw University established the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee of which Lewis, Lawson and Nash were founding members.

The campaign ultimately succeeded in desegregating many public facilities. At the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro on July 25, 1960, African American kitchen workers Geneva Tisdale, Susie Morrison and Aretha Jones removed their Woolworth's aprons and became the first African Americans to be served. Nash maintains the biggest effect of this campaign was the change it produced in the activists themselves, who began to understand their own power and the power of nonviolent direct action. Segregation would not become illegal until the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but Nash said it ceased to exist in 1960 everywhere blacks decided that “we were not segregatable” any longer.

Interpreting History

Six decades later, we often remember the work of the activists as we do many great moments of history. We create monuments and memorials and we honor the movement’s anniversaries and heroes. One of the great monuments to what took place at Greensboro and around the country is at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

In October 1993, curator William Yeingst heard on the news that the historic F. W. Woolworth in Greensboro was closing its department store as part of a downsizing effort. Yeingst and fellow curator Lonnie Bunch traveled to Greensboro and met with African-American city council members and the community. It was agreed that the counter should have a place at the Smithsonian Institution and volunteers from the local carpenters’ union removed an eight-foot section with four stools. Bunch, who is now the Secretary of the Smithsonian and was himself refused service at a North Carolina Woolworth's counter as a child, has said the sit-ins were “one of the most important moments in the 20th century.”

Nash has some reservations, however, for how this moment is commemorated, arguing that we need to develop a new way to remember a people’s movement like the struggle in which she took part. We are accustomed to thinking of history from the perspective of leaders and seminal moments. While the sit-in at Greensboro was incredibly significant, the courageous Greensboro Four and the counter enshrined at the Smithsonian attained their legendary status thanks to the individual work, sacrifice and action of thousands of people whose names we don’t know. Nash told me that remembering this history in a decentralized way is empowering. If we remember only the leaders and the important events, she says, “You’ll think, ’I wish we had a great leader.’ If you understood it as a people’s movement, you’d ask ‘what can I do’ rather than ‘I wish someone would do something.’”

Historian Jeanne Theoharis has argued that we tend to remember the past in a mythical way, with super-heroic leaders and an almost religious conception of the redemptive power of American democracy saving the day. Theoharis contends this misappropriation of history as a fable is not only wrongheaded, but dangerous, as it “provides distorted instruction on the process of change” and diminishes people’s understanding of the persistence of and wounds caused by racism.

Looking at the nation 60 years after they led such revolutionary change in its history, Nash and Lawson agree that similar work is just as important and still needed today. “The definitions of the words ‘citizen’ and of the word ‘activist’ need to be merged,” Nash says. She believes societies don’t collapse spontaneously, but over time due to millions of little cracks in their foundations. The work to repair those cracks must be the constant work of citizens. “If you are not doing your part,” she says, “eventually someone is going to have to do their part, plus yours.”

To these leaders, doing one’s part means better understanding and then following their example. Nash bristles when action like the sit-in campaign is referred to as a “protest.” “Protests have value, but limited value,” she says, “because ‘protest’ means just what it says. I protest, because I don’t like what you’re doing. But often the powers-that-be know you don't like what they're doing, but they're determined to do it anyway.”

Lawson agrees. “We have too much social activism in the United States that is activism for the sake of activism.” He continues. “We have too little activism that is geared toward systematic investigation—of knowing the issues and then organizing a plan to change the issues from A to B and B to C. There is a sort of demand of having immediate change, which is why so many people like violence and maintain that the power of violence is the power of change. And it’s not, it’s never been.”

Sixty years later, the activists still believe nonviolent action is the key to a better future and that the future is in our hands. As Joe McNeil, now a retired Air Force Major General, said when interviewed in 2017 for a new Smithsonian display of the lunch counter he made famous, “I walked away with an attitude that if our country is screwed up, don’t give up. Unscrew it, but don’t give up. Which, in retrospect, is pretty good for a bunch of teenagers.”

The Greensboro Lunch Counter is on view permanently at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Mira Warmflash provided research assistance for this article.

:focal(302x145:303x146)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/e0/00e03ee6-3943-4ad2-9752-be3d1d01fe89/greensboro-social.jpg)

:focal(1428x299:1429x300)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/06/16063c51-b65d-4769-819e-b24ad1e18175/woolworth-four-19601.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)