Bringing Thomas Jefferson’s Battered Tombstone Back to Life

The founding father’s fragile grave marker has survived for centuries, enduring souveniring, a fire and errant repairs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/e2/04e2a832-5245-4102-a2bf-b0fd6cbdfd74/20140930finaljeffstone014web.jpg)

On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, political rivals John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died just hours apart. Maintaining a steady correspondence throughout their final years, Adams a Federalist and Jefferson a Republican had grudgingly become friends. "You and I ought not to die until we have explained ourselves to each other," Adams wrote. But with his last breath as the story goes, he worried that his rival had outlived him. "Thomas Jefferson survives," were purportedly Adams' final words.

But Jefferson had died just hours ahead of him.

Adams is buried in a family crypt in Quincy, Massachusetts. But the post-mortem rivalry favors Jefferson if only for the curious tale of the long, peculiar journey of his grave-marker from Monticello, westward to Missouri and then two years ago making a stopover in the conservation laboratories at the Smithsonian Institution before heading home to the University of Missouri in August 2014.

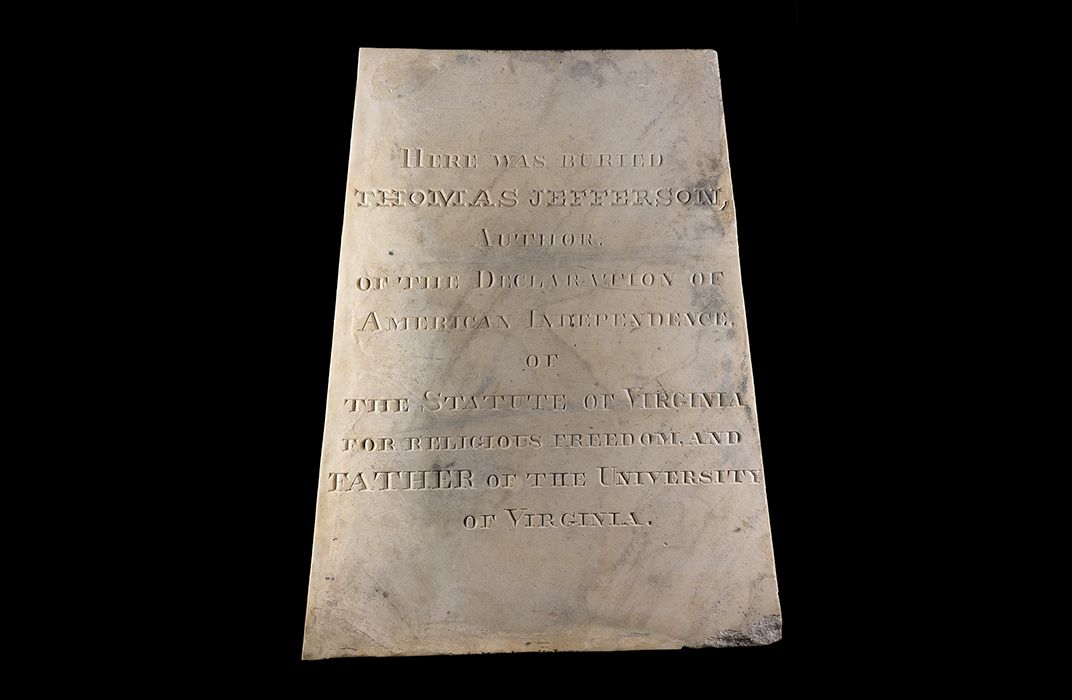

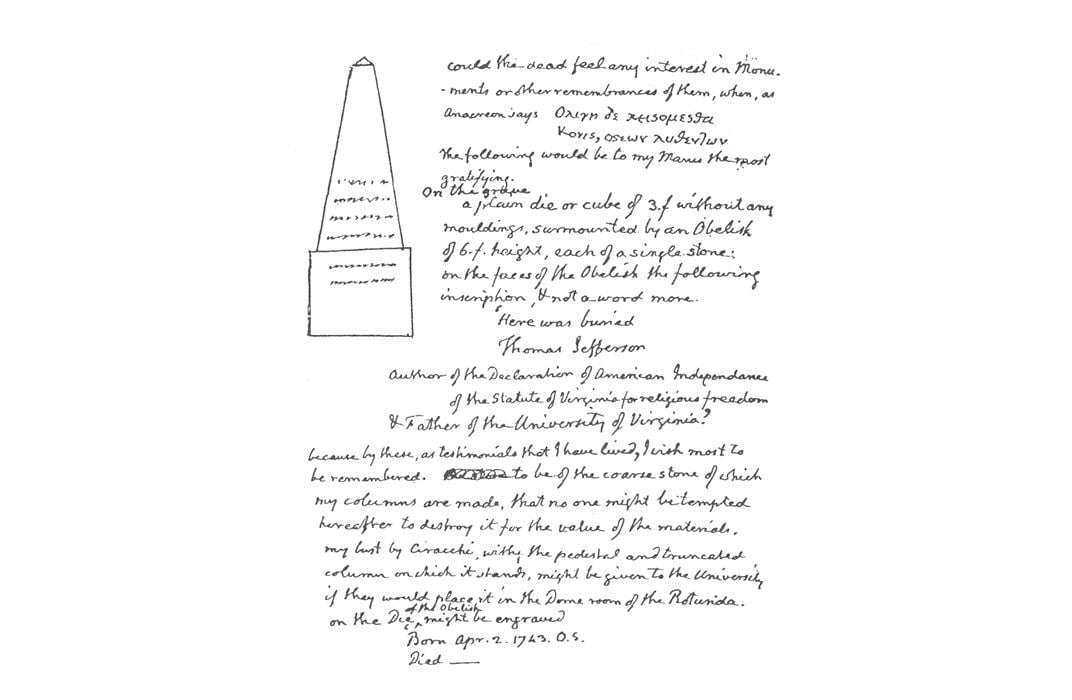

Jefferson's tombstone was no simple grave marker. The Founding Father left very detailed instructions for a three-part stone sculpture: a granite obelisk would sit atop a granite cube and be adorned with an inscribed marble plaque. Visitors flocked to Monticello to see it after it was erected in 1833. And souvenir seekers took to chipping off small chunks of the granite base. The marble plaque remained intact but soon loosened from the granite following the "rude treatment the monument received," wrote one observer at the time.

Horrified that the whole thing would soon be ruined, Jefferson’s heirs ordered a replica be placed at Monticello and donated the original three-part structure to the University of Missouri in 1883. Reasons for why the tombstone went to Mizzou are speculative, but among them is the belief that it was the first school founded within the territory that Jefferson secured with the Louisiana Purchase.

The tombstone and the plaque were put on display near the entrance to the school’s main building but the marble piece was soon brought inside for safekeeping.

Unfortunately, the building were it was stored burned down in 1892.

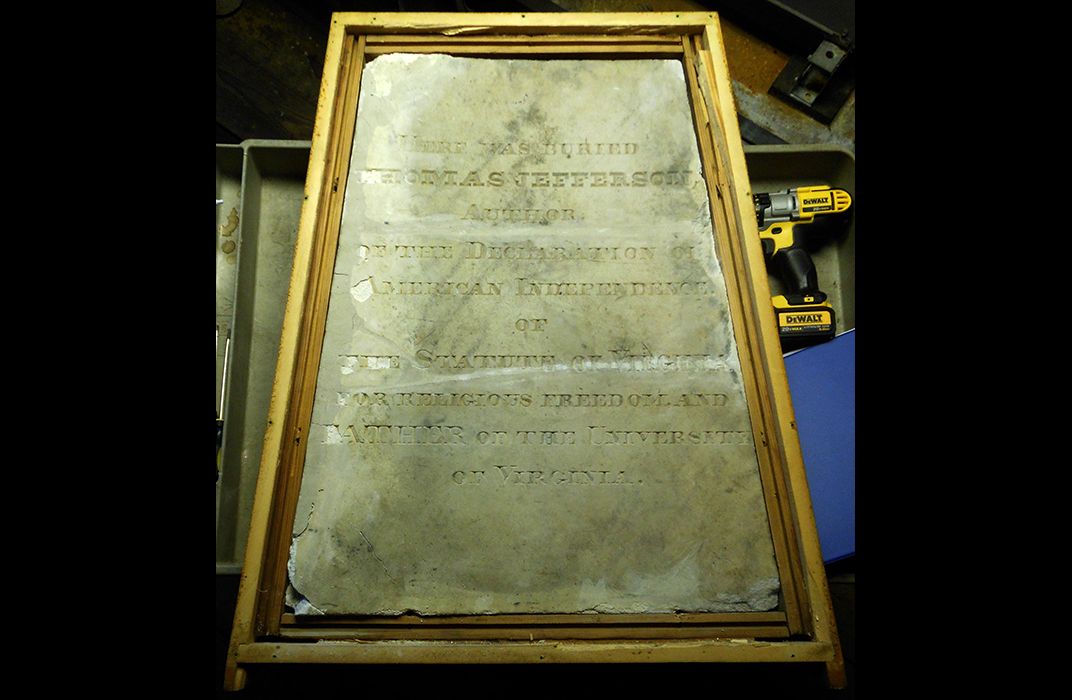

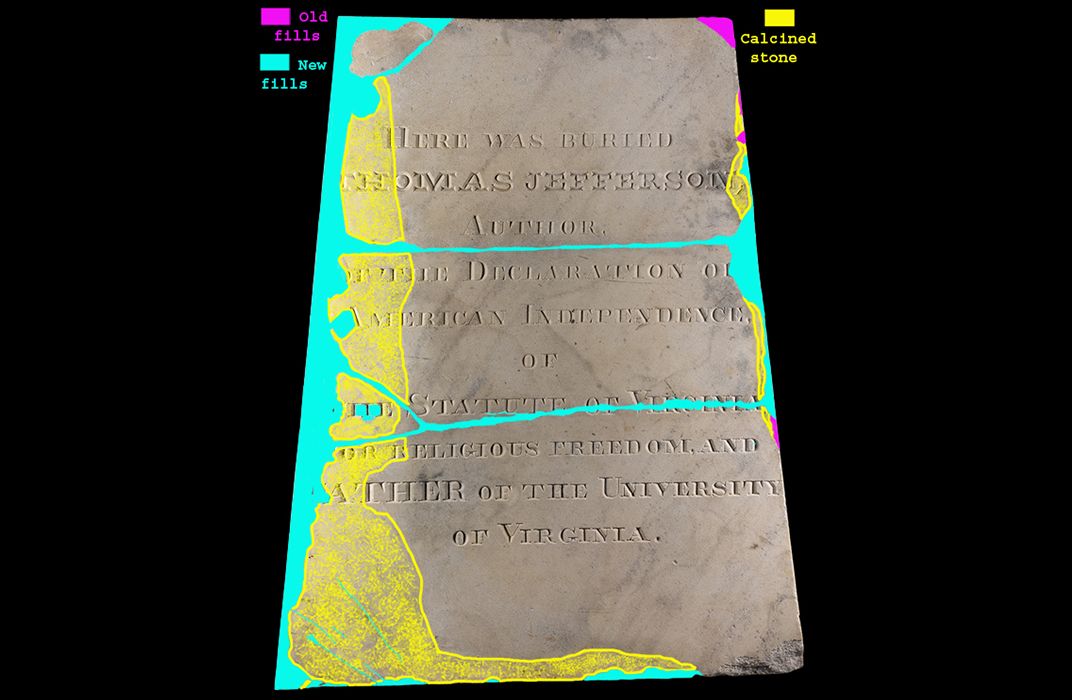

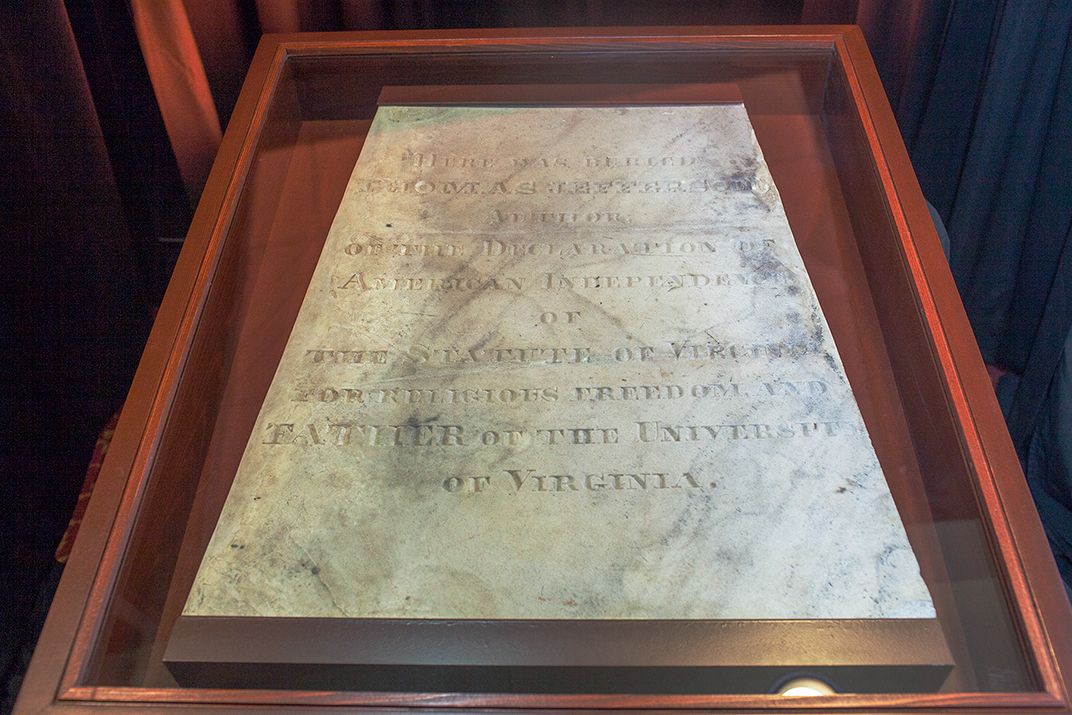

The plaque survived but the fire took a heavy toll. Shattered into five pieces and with portions crumbling at the edges, the piece was reassembled like a jigsaw and mounted in a plaster compound. No official report documented how it was reassembled or what materials were used. The plaque was then placed inside two wooden boxes, and again put away in an attic.

Fragmented, partially disintegrated, even burned and seemingly beyond repair, the marble plaque that marked Jefferson’s gravestone had become a modern-day Humpty-Dumpty tale by the time it arrived in the care of Carol Grissom, a conservator at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute.

For more than 100 years it had been stored in a wooden box in a dark corner of an unfinished attic at the University of Missouri, too fragile to be put on display. In 2005, a group of university administrators decided to do something about it.

And Grissom, it turns out, was able to do what all of the king’s horses and men couldn’t do for the fairy-tale egg: she found a way to put the marble plaque back together again.

In 2012, Grissom went to the University of Missouri to examine it. “It took a number of people to carry the box,” she says. They didn’t know it at the time, but whoever had tried to restore it after the fire, plastered another marble plaque onto the back.

Grissom had only seen the front of the plaque that day in the attic—which did have considerable losses, weaknesses and stains—when she agreed to take on the project. It wasn’t until she had the plaque in hand at the Smithsonian to fully examine it that she would understand its abysmal condition.

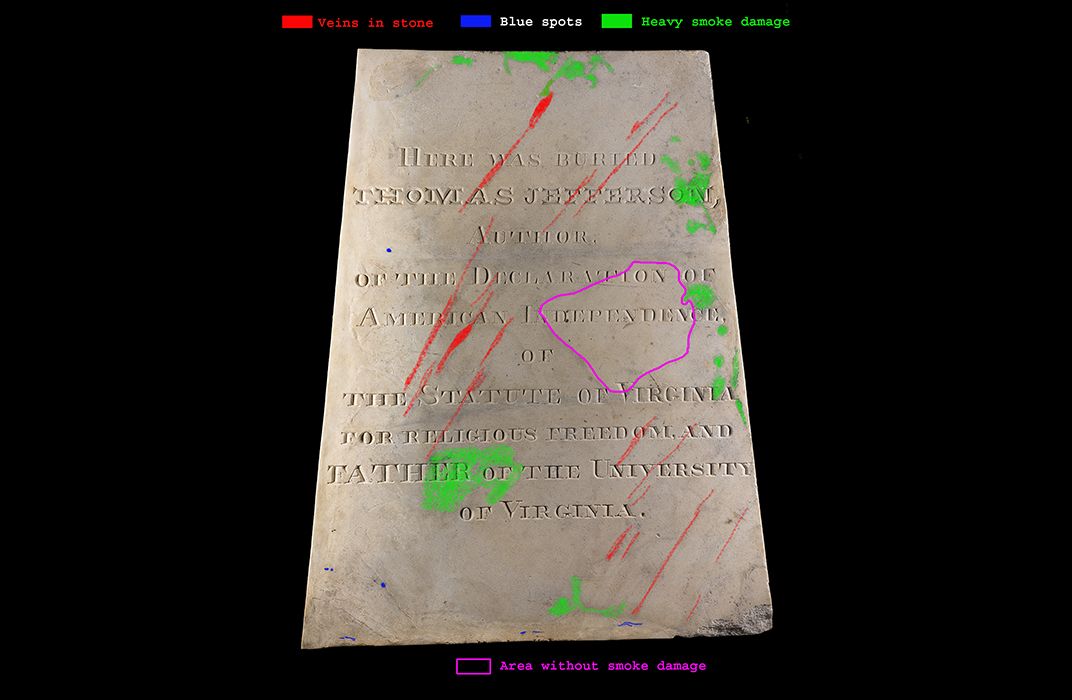

While a paper trail documents how the tombstone got from Virginia to Missouri, Grissom and others knew little else about its history. Where had the marble come from? Some had speculated it was imported from Italy. What were the mysterious dark stains on the face? Who tried to restore it after the fire and when? It was time to play detective.

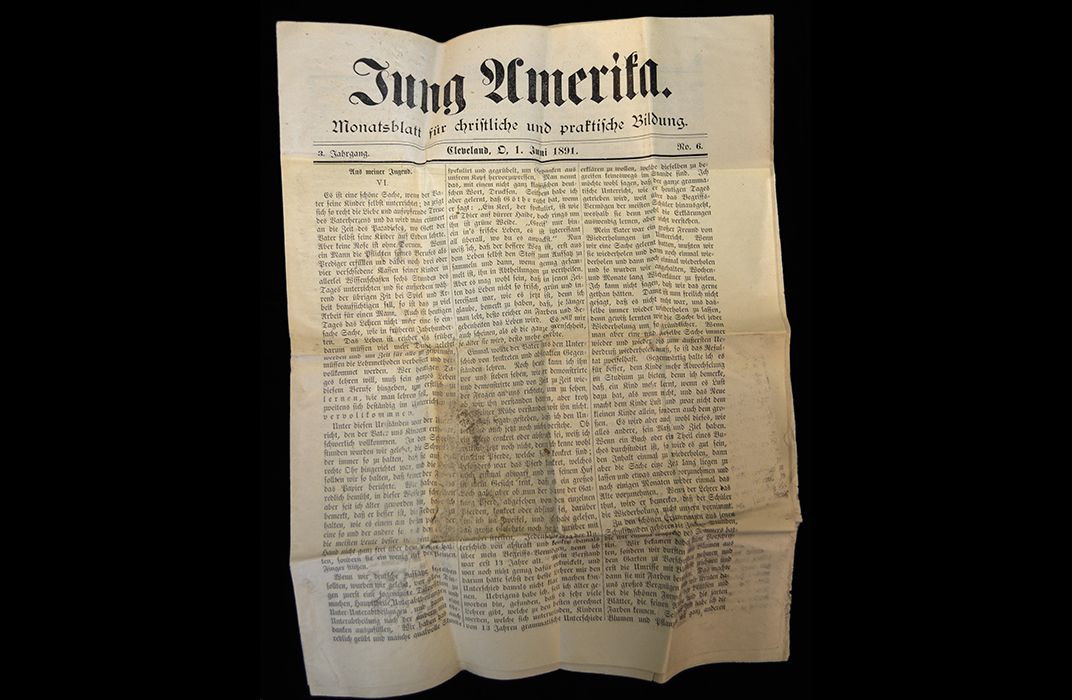

One mystery was solved almost immediately. Newspaper clippings cushioning the plaque confirmed that the initial restoration occurred shortly after the fire in the late 1880s. Grissom also realized that because the fragments were not aligned, whoever tried to reassemble the plaque did not glue the pieces together before placing them in the wet plaster atop the new marble backing.

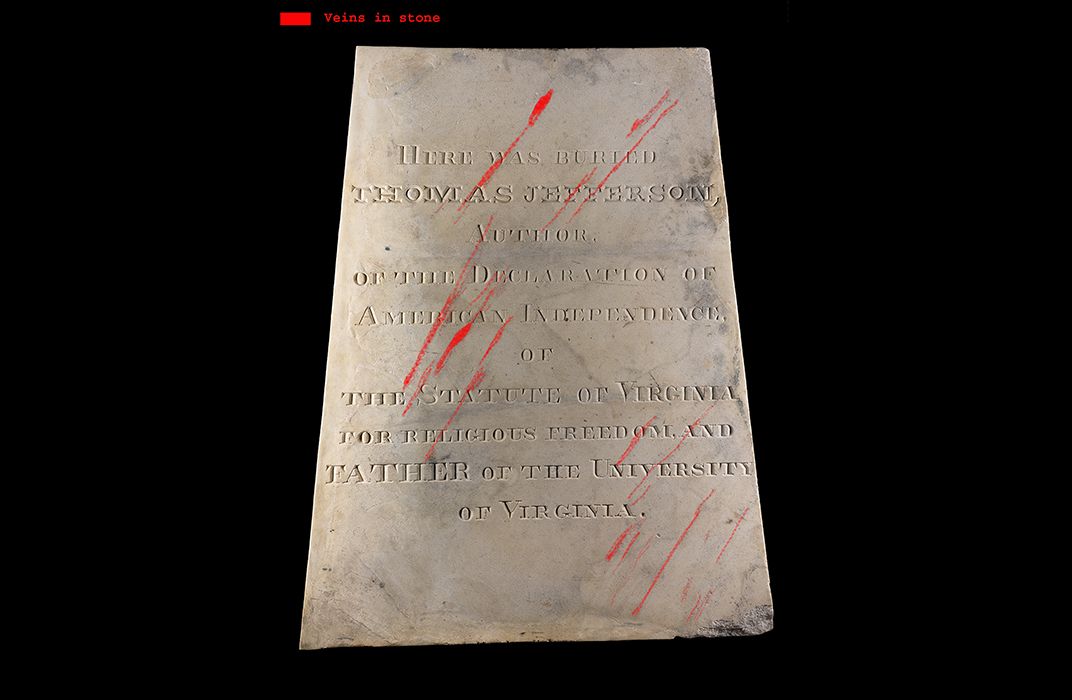

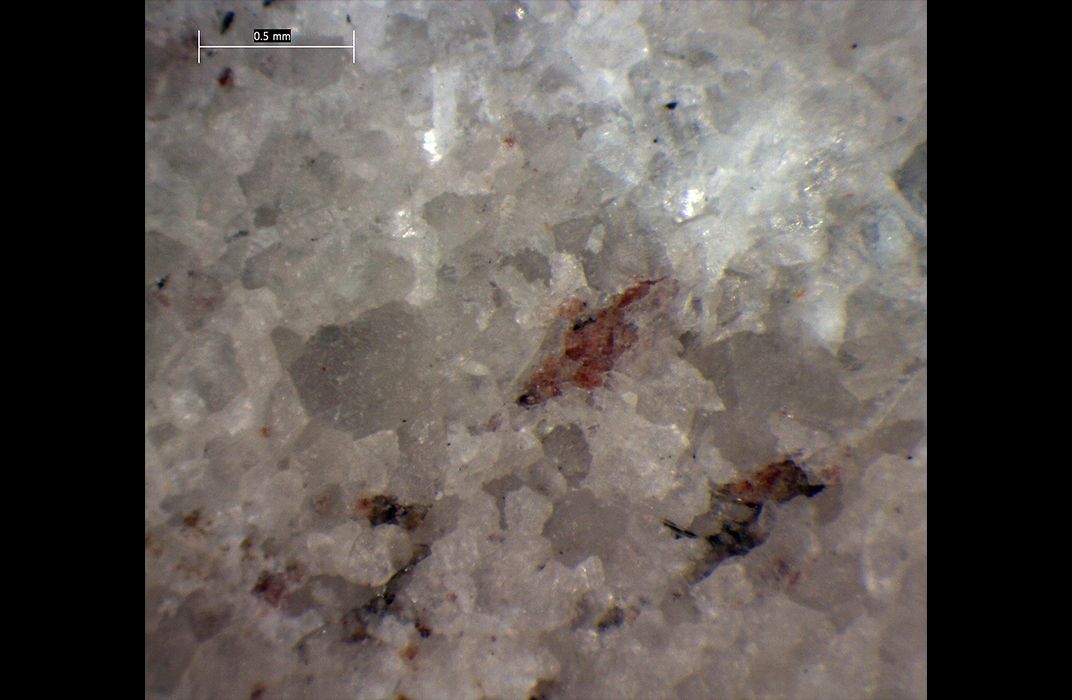

As for the mystery of the dark streaks on the surface—were they natural veins from other minerals? Smoke damage? Something else? “I tried scraping some of the black stuff with a scalpel, but that black is really quite mixed with the marble, so I would have had to dig a hole to get rid of all the black material,” she says.

Instead, she used a non-destructive scanning process to create maps of the elements present across square inch spots on the surface. If metallic elements existed in a dark spot, and didn’t show up elsewhere on the plaque, then she could determine whether or not the dark streaks were present in the original marble.

Her best guess, she says, is that during the fire, some type of plumbing system, or maybe metal hinges from the box it was stored in, melted and dripped on the plaque. “The materials deposited on the surface are still quite interesting and difficult to resolve,” she says.

Grissom and her team also cracked the mystery of the marble’s origin, determining through a stable isotope analysis, that the source of the marble was a quarry in Vermont.

Next, with dental picks, scalpels and files, Grissom set about removing the pieces from the plaster. She started with a small fragment on the upper-left side, in part to see if this would even be feasible, and in part because she couldn’t stand how misaligned it was. The experiment worked, and over the course of a few hundred hours, Grissom freed all five pieces from the backing, finishing in October 2013.

“Putting it back together was a lot quicker,” she says with a laugh. Grissom concocted a myriad of acrylic and epoxy putties—including one similar to the adhesive used on a broken sculpture at the Met—to glue the fragments together and fill in space where there were losses. After painting the surface to look natural again, she embarked on the painstakingly slow process of re-carving the inscription.

The plaque was as good as new—or, as close to new as possible—but the work wasn’t done.

When the University of Missouri commissioned the project, they also asked for two replicas of the tombstone. For this, a team of experts from the Smithsonian’s Office of Exhibits Central had to be called in.

To simplify a process called photogrammetry—a process that is anything but simple—hundreds and hundreds of photographs of the plaque were taken from all angles, and put into a computer program that created a 3D image of it. Then the information was sent to a computer numerical control (CNC) machine that carved a model of the stone into a polyurethane board. From there, a silicone mold was made to cast replicas, and they were painted to match all the nuances of the original.

In September 2014, the three plaques were returned to the University of Missouri. One of the replicas is used for teaching, and the other is adhered to the original granite obelisk and prominently displayed in the main campus quad. As for the original plaque? It is proudly on display in the main campus building.

So yes, Mr. Adams, Thomas Jefferson survives.