Life Bounced Back After the Dinosaurs Perished

The devastation was immediate, catastrophic and widespread, but plants and mammals were quick to take over

:focal(587x464:588x465)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/af/eeaf0cba-527e-4e95-8e24-3db49754e3d0/istock39120756mediumweb.jpg)

When a six mile-wide asteroid struck the Earth 66 million years ago, it was one of the worst days in the history of the planet. About 75 percent of the known species were rapidly driven to extinction, including the non-avian dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus, the flying pterosaurs, the coil-shelled squid cousins called ammonites, and many more.

Life was not totally extinguished, however, and the close of the Age of Dinosaurs opened up the path to the Age of Mammals. Now a new study has helped put a timer on how quickly life bounced back from the devastation.

In a new Earth and Planetary Science Letters paper, Smithsonian's Kirk Johnson, director of the National Museum of Natural History, geologist William Clyde of the University of New Hampshire and their coauthors draw from the fossil and rock record of the Denver Basin to determine what happened after the devastating asteroid impact. The region located in eastern Colorado and extending into Wyoming and Nebraska is one of the best places in the world to examine the change.

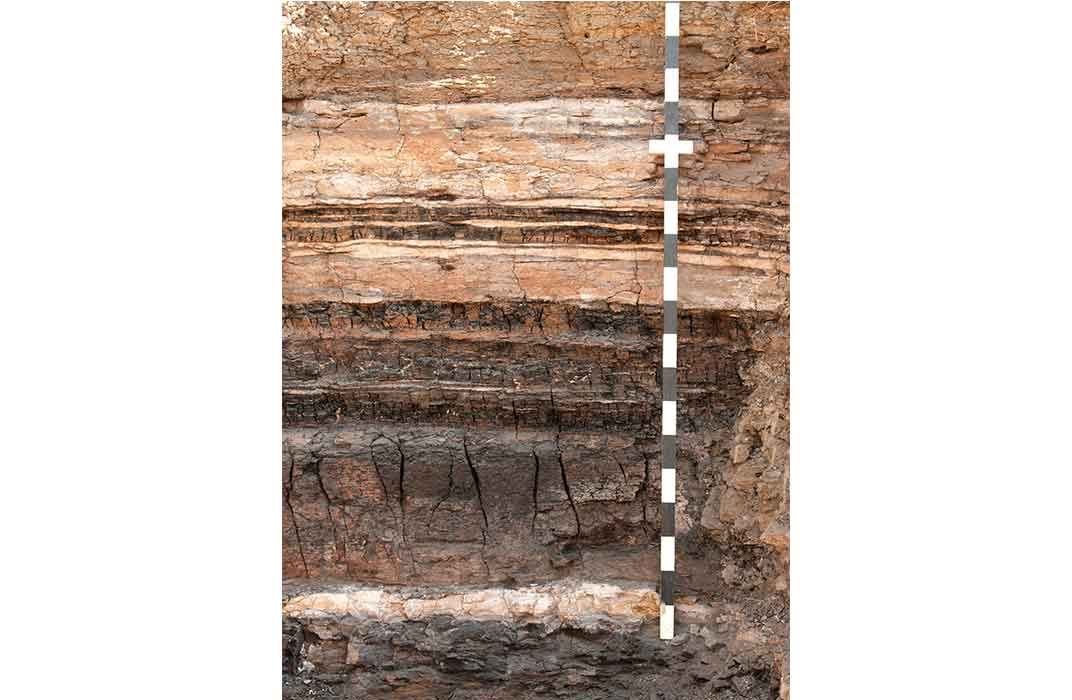

“The Denver Basin was actively subsiding, and the adjacent Colorado Front Range was actively uplifting, during the last four million years of the Paleocene,” Johnson says, meaning “the basin was acting like a tape recorder of local events.” Better still, he says, nearby volcanic eruptions spewed enough ash that geologists now have hundreds of layers that can be given absolute dates to determine the age of these rocks.

These rocks provide a more precise timing for what’s seen in the fossil record.

The change between the Late Cretaceous and the subsequent Paleogene period is stark. “The Late Cretaceous was forested and warm,” Johnson says, with forests dominated by broadleaf trees, palms and relatives of ginger. Then the extinction struck, stripping away the big herbivorous dinosaurs and, says paleobotanist Ian Miller of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, about 50 percent of plant species. The surviving species created a new landscape. “Within two million years of the impact, the Denver Basin had the world’s first known tropical rainforests and mammals of medium body size,” says Johnson.

The new study focuses on what happened between those points. Using a technique known as uranium-lead dating, the geologists determined that the K/Pg boundary (the layer that records the asteroid strike and marks the divide between the Cretaceous and subsequent Paleogene period) was 66.021 million years ago.

Turning to the timing of the fossils, Johnson and colleagues estimate that the time between the last known non-avian dinosaurs and the earliest Cenozoic mammal was about 185,000 years, and no more than 570,000 years. That’s just a blip from the perspective of Deep Time—the incomprehensible span of ages in which the whole of human history is just a footnote.

The landscape during this transition didn’t resemble the Cretaceous forests or the sweltering rainforests that came after. Fossil pollen records show that there was what paleontologists refer to as a "fern spike"—when these low-growing plants proliferated over the landscape—that lasted about 1,000 years. That’s because ferns thrive after disturbances, Miller says. “They just need a little bit of substrate and water and they are off.”

The dates and fossils speak to how dramatically the extinction changed the planet. Not only was the mass extinction extremely rapid, but life recovered relatively quickly as well. There was less than half a million years between the likes of Triceratops and the time when the surviving mammals started to take over the basin’s recovering ecosystems. “The new paper really drives home the point that the extinction was, from a geological standpoint, immediate, catastrophic and widespread,” Miller says.

Studies like these are offering ever-greater resolution of scenes from the deep past.

“Geochronology is getter better and more precise all the time, and this study applies it to a unique outcrop that is unparalleled in its ash bed sequence,” Johnson says. He adds that studying such patterns isn’t just ancient history. “The K/Pg was both instant and global, so it is a very interesting analogy for the industrial Anthropocene of the last century,” Johnson says.

By studying the past, we may catch a glimpse of the future we’re creating.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)