Listen to the Freedom Songs Recorded During the March From Selma to Montgomery

When MLK called for people to come to Selma, Detroit’s Carl Benkert arrived with his tape recorder, making the indelible album “Freedom Songs”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/c7/dfc7c195-e840-4d27-a748-a9980a7336fa/fp001385web.jpg)

Of the songs heard during the credits following the acclaimed Ava DuVernay film Selma, one of them, performed by John Legend and the rapper Common, already won the Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination.

But another track in the credits features the very voice of the marchers, whose songs of hope, defiance and unity were directly captured and documented by a man who carried a large tape recorder under his coat. Carl Benkert was a successful architectural interior designer from Detroit who had come down South in 1965 with a group of local clergy to take part and bear witness to the historic march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, for voting rights.

In addition to his camera, he brought a bulky, battery-operated reel-to-reel tape recorder to capture the history all around him, in speech but also in song. In their struggles to make a stand against inequality, Benkert wrote, “music was an essential element; music in song expressing hope and sorrow; music to pacify or excite; music with the power to engage the intelligence and even touch the spirit.”

(Note: to hear the songs in the playlist below, you must have a Spotify account, but it is free to register with them.)

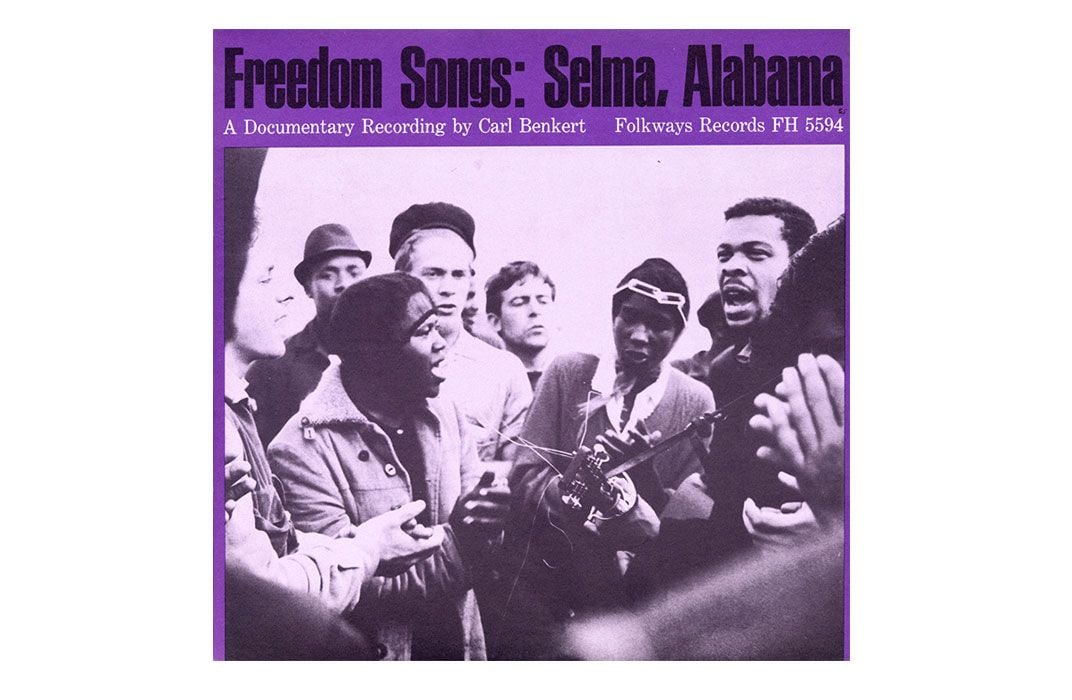

So stirring were the tracks he captured in churches and marches that they were recorded on a Folkways Records album within a matter of months. The resulting “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama,” released 50 years ago and which has never been out of print, is one of two Smithsonian albums covering the era. It is that most unusual of albums—an authentic documentary of the marches for voting rights as well as a compendium of march songs that would inspire and be used in marches for freedom ever since. (The Smithsonian acquired Folkways in 1986 after the death of its founder Moses Asch and continues the label as Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.)

“I was really pretty thrilled,” said Catherine Benkert, when she learned that her father’s recordings were in the film. “I told everybody I knew. He would have been thrilled too.” The elder Benkert died in 2010 at 88 and had been a lifelong amateur audio documentarian.

“He made a point of being at some of those important junctures of the 20th Century,” says a family friend Gary Murphy.

“He made a recording of the last steam engine trip that went between Pontiac and Detroit—in stereo,” Benkert adds. “And that was back when stereo was brand new.” Why did he go to Alabama? “Dr. King called for people to come and he felt moved to do it,” she said in a phone interview from her home in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

While in Alabama, Benkert and others from the Detroit area were enlisted to be night watchmen for the marchers, to keep sure things remained safe overnight, she said, “making sure nothing was happening there.”

In the daytime, Benkert had his tape recorder at the ready, albeit behind an overcoat that cloaked it from police or angry whites. Songs rose frequently. “He told me that when people were scared down there, people would sing, “ Murphy said. The track used in “Selma” was a percussive-heavy medley of “This Little Light of Mine / Freedom Now Chant / Come by Here” recorded at Zion Methodist Church in Marion, Alabama, where Jimmie Lee Jackson was beaten by troopers and shot by a state trooper while he was participating in an earlier peaceful voting rights rally.

The killing inspired the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights that culminated at Edmund Pettus Bridge across the Alabama River a month later.

An evening mass meeting on March 18, 1965, at the church where Jackson had been a deacon “was attended to overflowing by residents and visitors who had spent the day working in the counties north of Selma,” Benkert recalled in the liner notes in his album.

In the medley, the familiar, optimistic song of determination, “This Little Light of Mine,” driven by percussive clapping, shifts to the familiar and still heard “Freedom! Now!” chant, before the entreaty for heavenly support: “People are suffering, Lord, come by here/ People are dying, my Lord, come by here.”

For Benkert, traveling to Selma in those charged times provided the opportunity “to see life in a vital totality never otherwise experienced,” he wrote. It was a moment that permanently affected him, judging from his comments on the Zion Methodist mass meeting. “Participating in ‘We Shall Overcome’ is always a moving occasion for the spirit,” Benkert wrote, “but this was for the few outsiders present the most powerful and electrifying yet experienced.”

And a number of his recordings of speeches, particularly by Martin Luther King, have had historic importance. Benkert made the only known recording of a May 31, 1965, King speech that came at the end of the march to Montgomery, that had grown to 50,000 people during its five days. In it, King told supporters at Brown Chapel in Selma, “Equality is more than a matter of mathematics and geometry. Equality is a philosophical and psychological matter and if you pluck me from communicating with a man at that moment you are saying that I am not equal to that man.

“Let us not rest until we end segregation and all of its dimensions,” King said. Benkert donated the bulk of his recordings and papers to the University of Michigan before his death, but royalties for the Selma recordings still come in, his daughter said.

“To be still in print after 50 years, it’s got to be part of the fabric of the whole American story,” says Murphy. “It will probably never go away.”

And the attention of the “Selma” movie may bring new audiences to the original recordings, Ms. Benkert said. “His whole thing, with any of his recordings, was: he wanted people to hear them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)