Nearly every day while writing my new book, The Age of Acrimony: How American’s Fought to Fix Their Democracy, I would walk across the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to my office at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. I’d pass tourists wearing MAGA hats and protestors waving angry signs. In the museum’s secure collections, I’d settle into the cool, quiet aisles that preserve the deep history of our democracy. There, century-old objects—torches from midnight rallies, uniforms from partisan street gangs, ballots from stolen elections—told a forgotten drama of fractious and furious partisanship.

Most people don’t often think about the politics of the late 1800s. Call it “historical flyover country,” an era stranded between more momentous times, when U.S. presidents had funny names and silly facial hair. But for our current political crisis, this period is the most relevant, vital and useful. The nation's wild elections saw the highest turnouts and the closest margins, as well as a peak in political violence. Men and women campaigned, speechified and fought over politics, in a system struggling with problems all too familiar today.

In 1910, the influential Kansas journalist and eventual leader of the progressive movement William Allen White wrote: “The real danger from democracy is that we will get drunk on it.” White’s warning about the intoxicating potential of politics came at a turning point, just as the raucous politics of the 1800s were sobering up into the more temperate style of 20th-century America.

The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865-1915

The Age of Acrimony charts the rise and fall of 19th-century America's unruly politics.This is the origin story of the “normal” politics of the 20th century. Only by exploring where that civility and restraint came from can we understand what is happening to our democracy today. In telling the tale of what it cost to cool our republic, historian Jon Grinspan reveals our divisive political system's enduring capacity to reinvent itself.

Though we rightly think of 19th-century politics as exclusionary, American democracy held revolutionary new promise in the mid-1800s. For all its flaws, the nation was experimenting with a bold new system of government—one of the first in world history to give decisive political power to people without wealth, land or title. Working-class voters predominated at the polls. Poor boys grew up to be president. And reformers fought for votes for women and Black Americans.

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, with slavery dead, the old aristocracy vanquished, and four million formerly enslaved people hoping for new rights, Americans began to talk about “pure democracy.” That concept was never well defined, but for many activists, it meant that it was time for the people to rule. But how to get a busy, distractable, diverse nation to participate?

Decades earlier—from the 1820s to the 1850s—campaigners tried to engage voters by building bonfires, holding barbecues and offering plenty of stump speeches while handing out booze. Then, on the eve of the Civil War, supporters of Abe Lincoln’s hit on a new style. Lincoln’s Republican party introduced the “Wide Awakes” clubs to America. Gangs of young partisans, wearing dark, shimmering martial uniforms and armed with flaming torches, stormed through towns and cities in midnight marches. For the half century after 1860, every political campaign worth mentioning borrowed this approach, organizing massive rallies of tens of thousands of uniformed, torch-waving marchers. Diverse crowds turned out, from boisterous veteran voters to rowdy boys, from grandmothers to young women, from journalists armed with pens to political rivals armed with their revolvers.

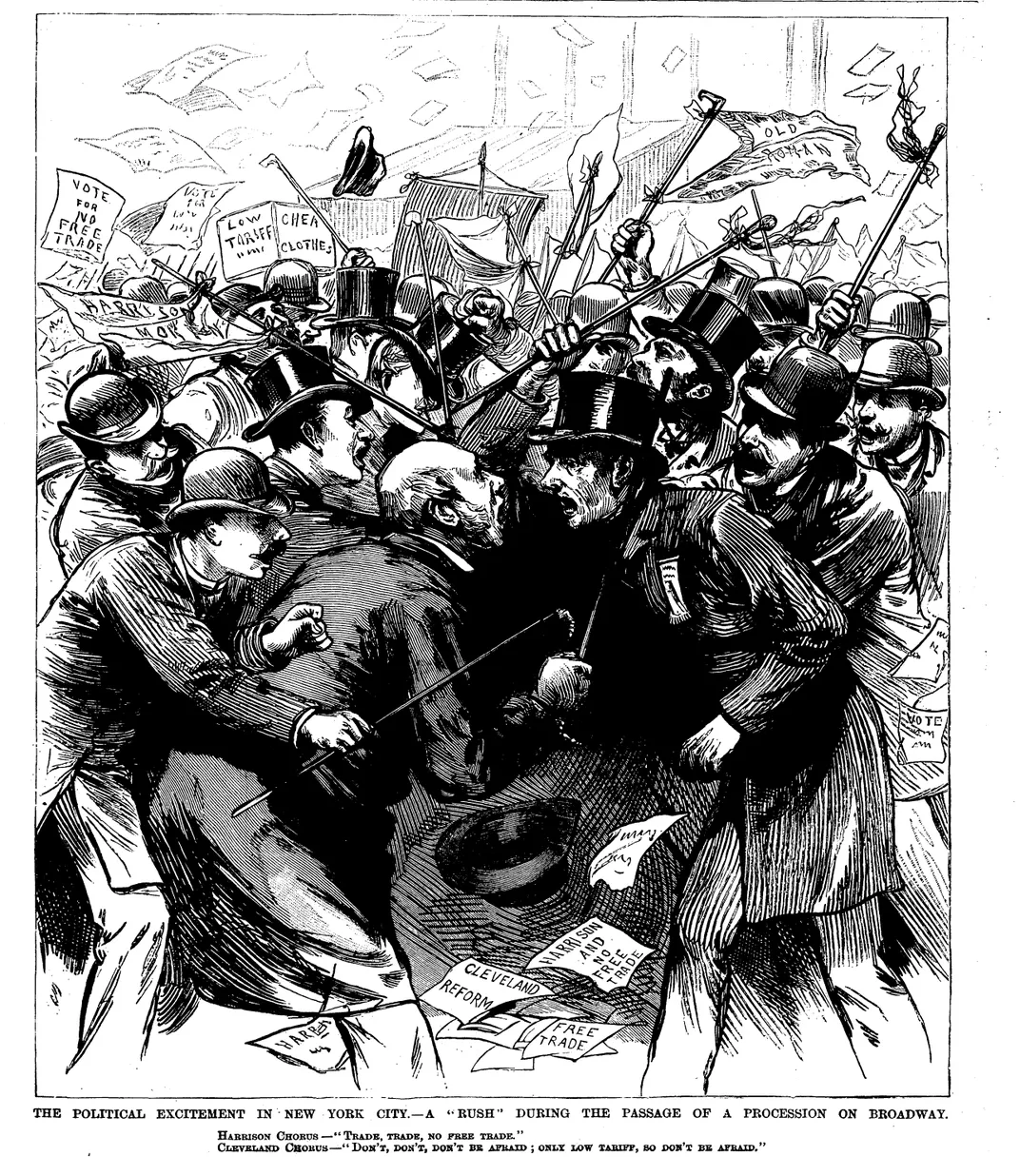

Such public politics became, in the words of one comedian, “our great American game.” Political rancor grew precipitously. Saloons resounded with heated debates. On train cars, Americans took straw polls to see how strangers would vote. At dinner tables, families bonded—or broke up—debating an upcoming race. Even when exhausted Americans threw down their newspapers, they looked up only to find partisan broadsides slathered on every wall. “Ignorance is bliss now,” complained one woman as she canceled her political newspapers, weary of the whole spectacle.

For voters, participation meant an even deeper immersion. Election Day was a communal, combative, boozy bacchanal. White’s metaphor was apt, when people voted, they literally got drunk on Election Day. One Norwegian wrote home from Chicago, remarking that “it was fun to see” crowds of workers leaving their factories to go vote, “either before or after stopping at a bar.” During the 1876 election, which drew an unprecedented 81.8 percent turnout—Rutherford B. Hayes’s campaign handed out massive oversize beer steins, despite the fact that Hayes and his wife were devout teetotalers.

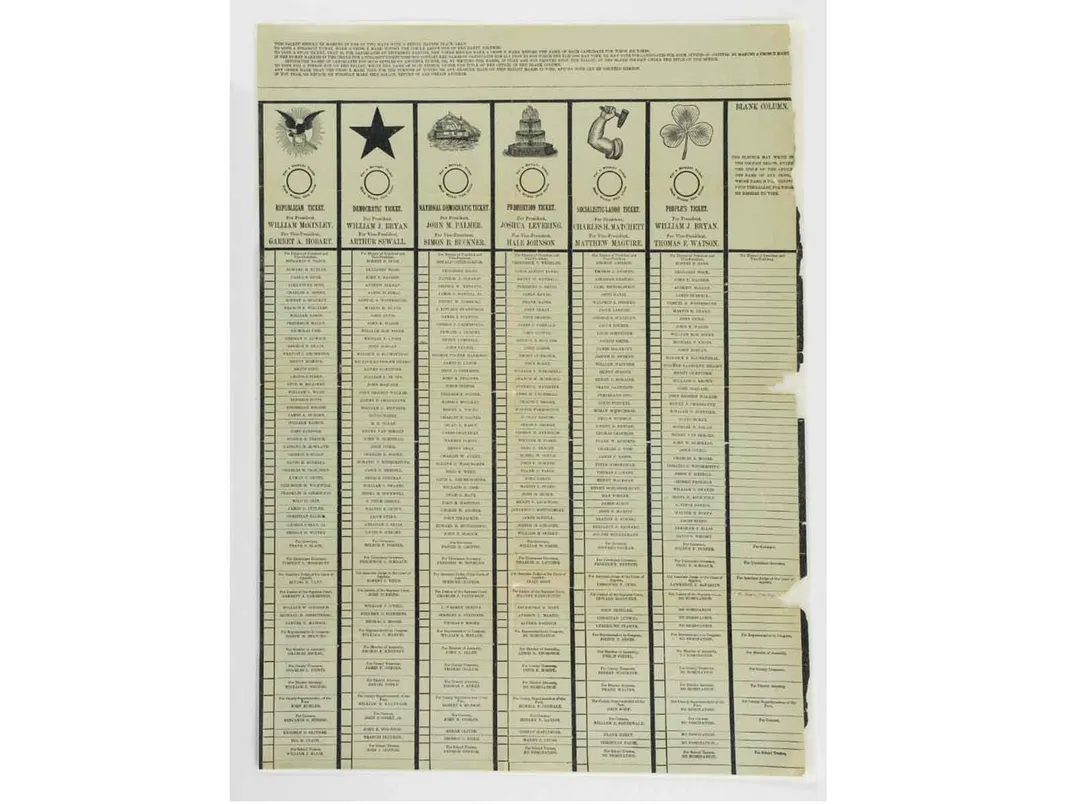

All the carousing culminated at a rambunctious polling place, when a voter selected a colorful ticket from his party’s ballot “peddlers,” made his way past the opposing party’s intimidating “challengers,” and placed his vote in a wooden or glass ballot box. Amid singing, shouting and heckling from the other voters in his community, it was a scene of heated, convulsive political theater. The system seemed designed to take over life, distort opinions, attract bad actors, raise voices and destroy civility.

In northern cities, a sneering establishment worried that the system was dominated by a working-class majority who could always outvote them. The celebrated Boston aristocrat Francis Parkman famously complained that democracy didn’t work in his 1878 “The Failure of Universal Suffrage,” a screed that claimed that the voters were “a public pest” and that the real threat to America came not from above, but beneath. Belief in equality and majority rule, Parkman argued, was destroying America.

Equal suffrage met even more aggressive attacks in the South. White supremacist ex-Confederates, who lost the war and had remained on the fringes of politics for most of a decade after, used the Democratic party to terrorize Black voters, end Reconstruction and dramatically suppress voter participation. Within a few short years of the end of slavery, one million formerly enslaved Americans became voters, but most lost their rights nearly as quickly as Reconstruction ended and the Jim Crow era began.

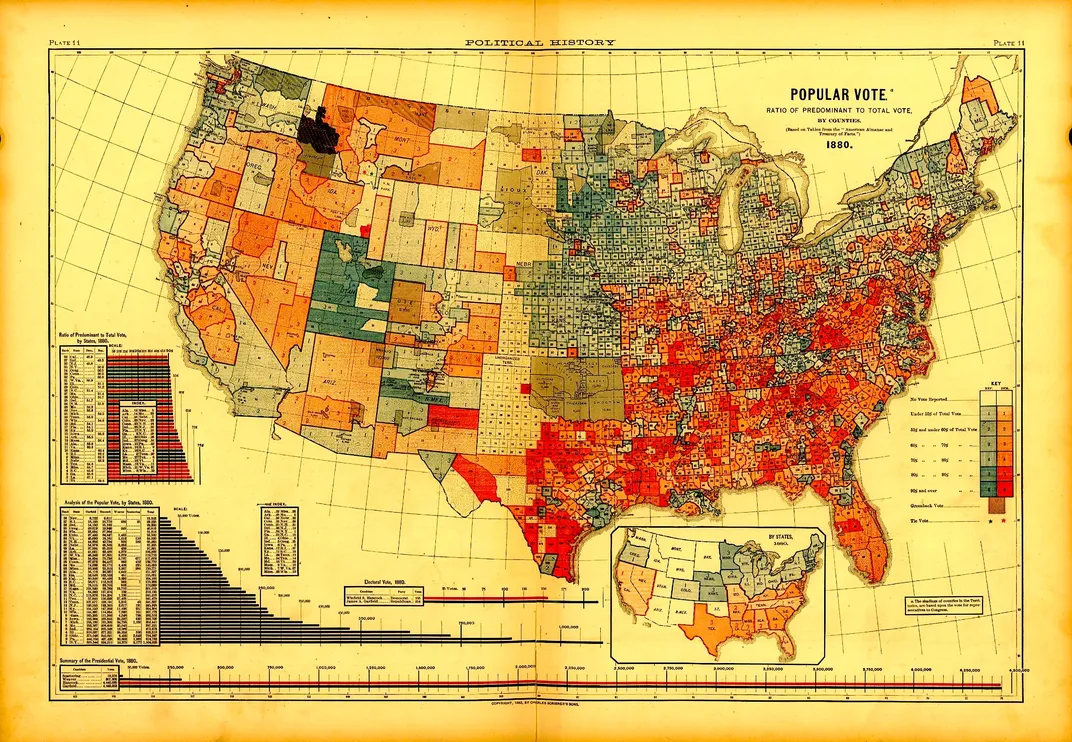

In the North, voter turnouts peaked from 1876 to 1896, and elections were never closer. No president in this period came to office by winning a majority of the popular vote. Even with racial issues falling out of the national spotlight, fights over money and inequality fired up voters.

Though the electorate turned out in huge numbers, marchers filled squares and newspapers attacked rivals, politics failed to bring real change. This system—overheating and yet standing still—led only to anger and agitation. In 1881, the mentally ill drifter Charles Guiteau, who had campaigned for President James Garfield at torchlit rallies, felt slighted and decided that America would be better off if the “President was out of the way.” So Guiteau bought the largest pistol he could find, and shot Garfield—the murder was the second assassination of a president in just 16 years. Within two decades, another madman would gun down President William McKinley. And every seven years, on average, a sitting congressman was murdered.

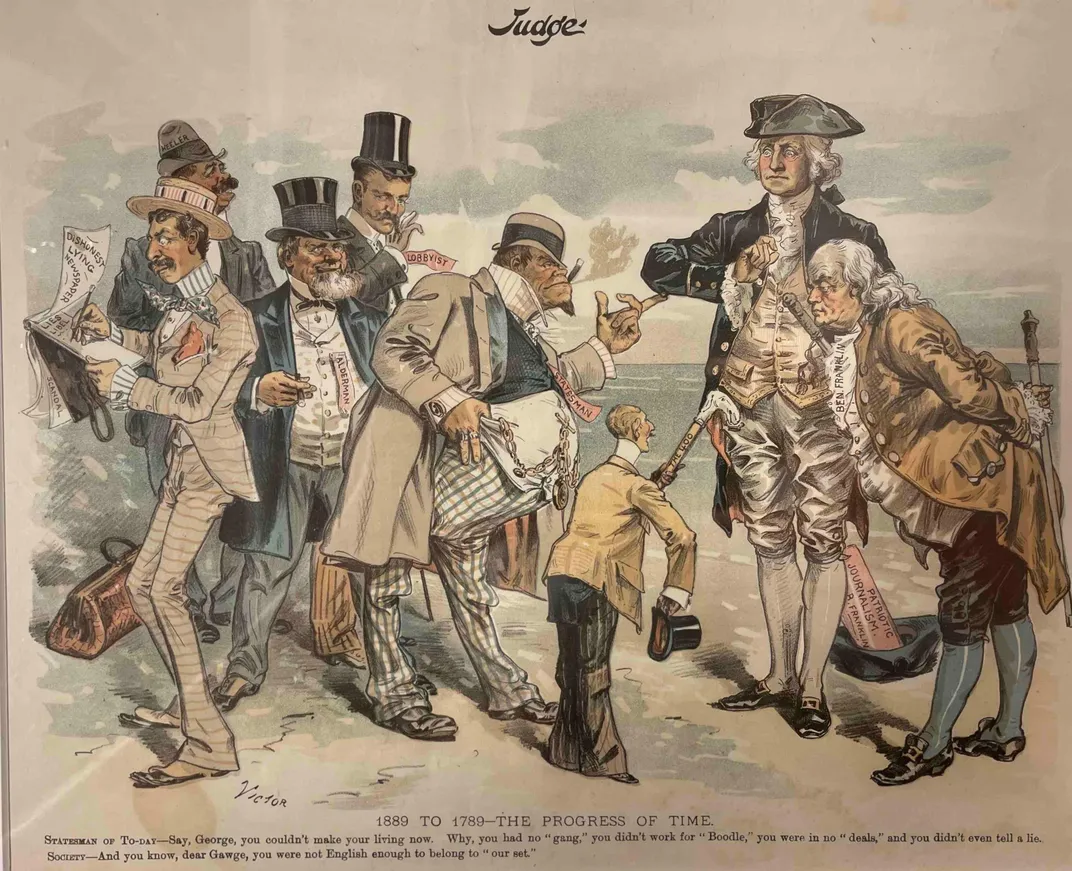

American politics had hit on an amazing ability to mobilize citizens, but also to agitate them to unspeakable violence. Citizens looked for someone to blame. Presidents were criticized, but really the executive branch was so weak that they could do very little. Powerful party bosses often nominated friendly, malleable do-nothings to the job. More people blamed politicians as a class. Brilliant cartoonists like Thomas Nast and Joseph Keppler mocked politicians as snarling beasts, overfed vultures, sniveling rats and thuggish bosses. Others attacked the rising immigration rates, like Francis Willard, the leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, who blamed America’s out-of-control politics on “alien illiterates.” Others still aimed (more accurate) attacks at railroads, corporations, robber barons and lobbyists who seemed to be buying up America. The muckraking reporter Henry Demarest Lloyd wrote that “liberty produces wealth, and wealth destroys liberty.”

Everybody, it seemed in the grumpy 1880s, had someone to blame for why democracy was failing.

Some well-to-do reformers blamed, not individuals or groups, but the culture and etiquette of American democracy. All those noisy rallies were nothing more than a “silly sort of show,” those busy polling places were “vulgar,” “venal” and “filthy.” American democracy, a growing upper middle-class movement argued, needed an intervention, and in an era of Temperance politics, reformers knew just how to achieve it.

First, they went after the booze. Reform organizations pulled the liquor licenses from political fundraisers, closed saloons on Election Day and passed prohibition laws on the county and state level. Voters were more clearheaded, but those partisan saloons had been key institutions for working-class men. Shutting them down meant shutting many out.

Cities banned marches without permits and used police and militias to punish unlawful assembly. And parties desperate to win over “the better class of people,” as one reformer put it, stopped paying for torches, uniforms, fireworks and whiskey. Campaigners shifted from thrilling street-corner oratory to printed pamphlets. To some, these changes looked like innovations. The Los Angeles Times cheered the citizens who had spent previous elections “on the street corner shouting, or in the torchlight procession,” but could now be “found at home” reading quietly.

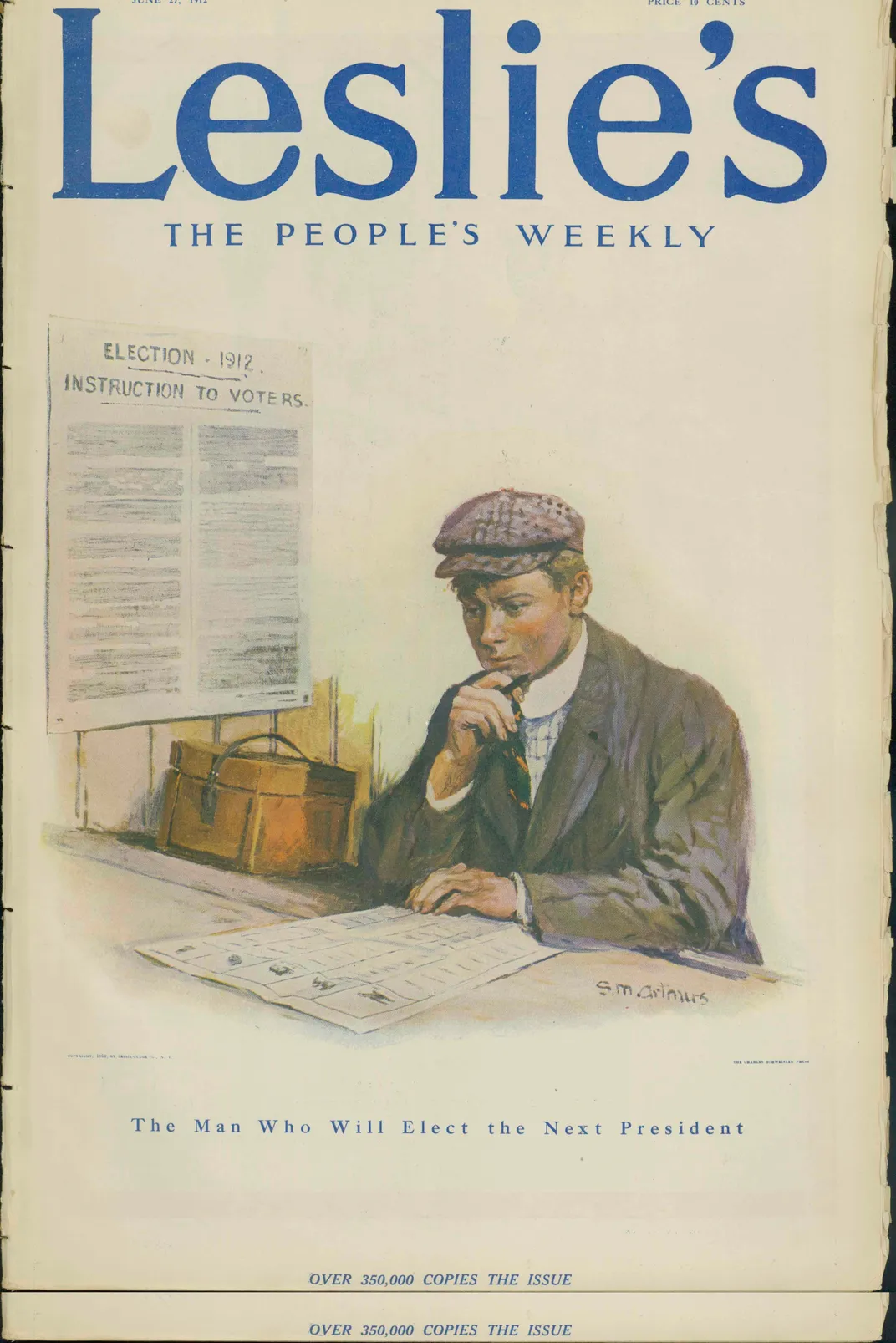

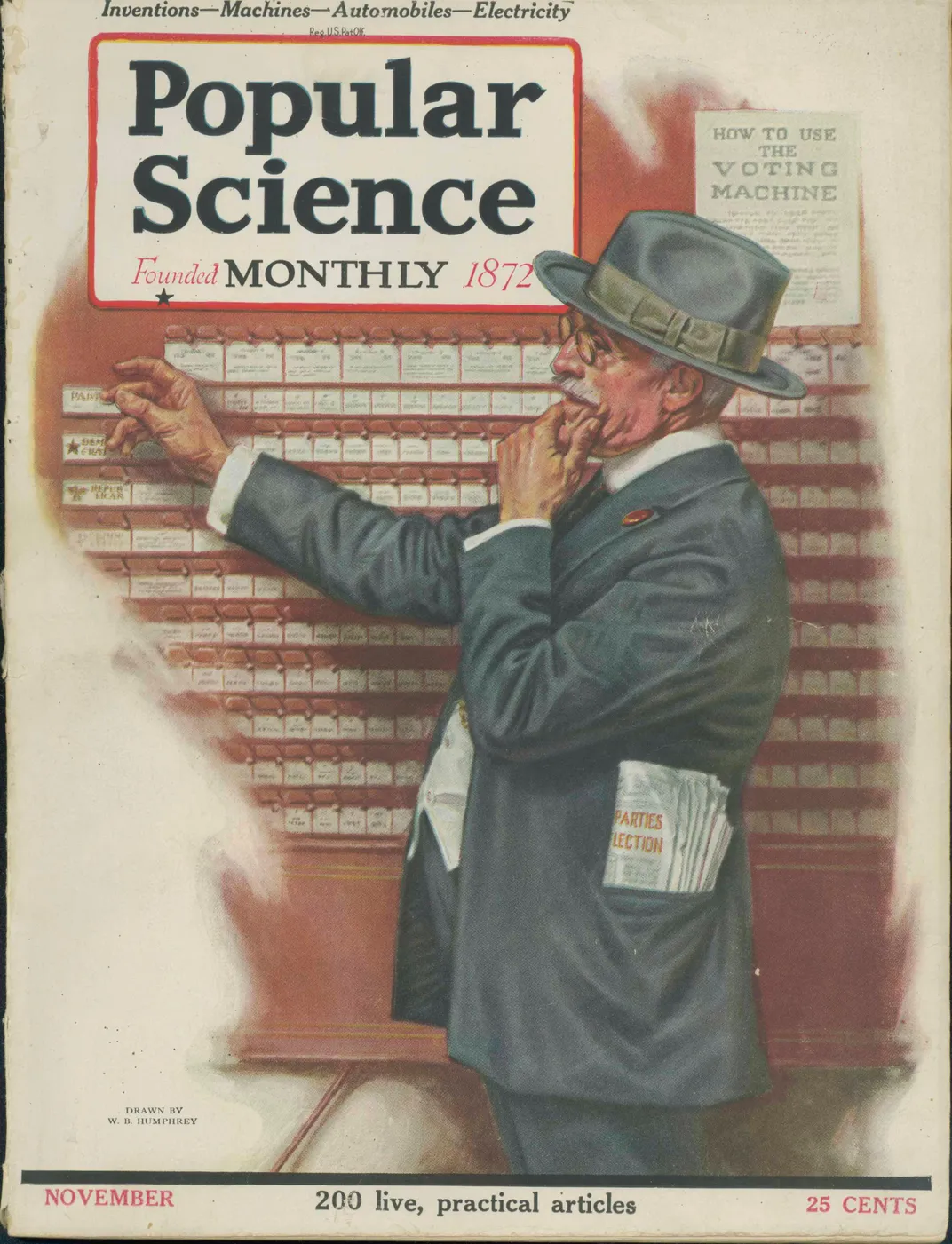

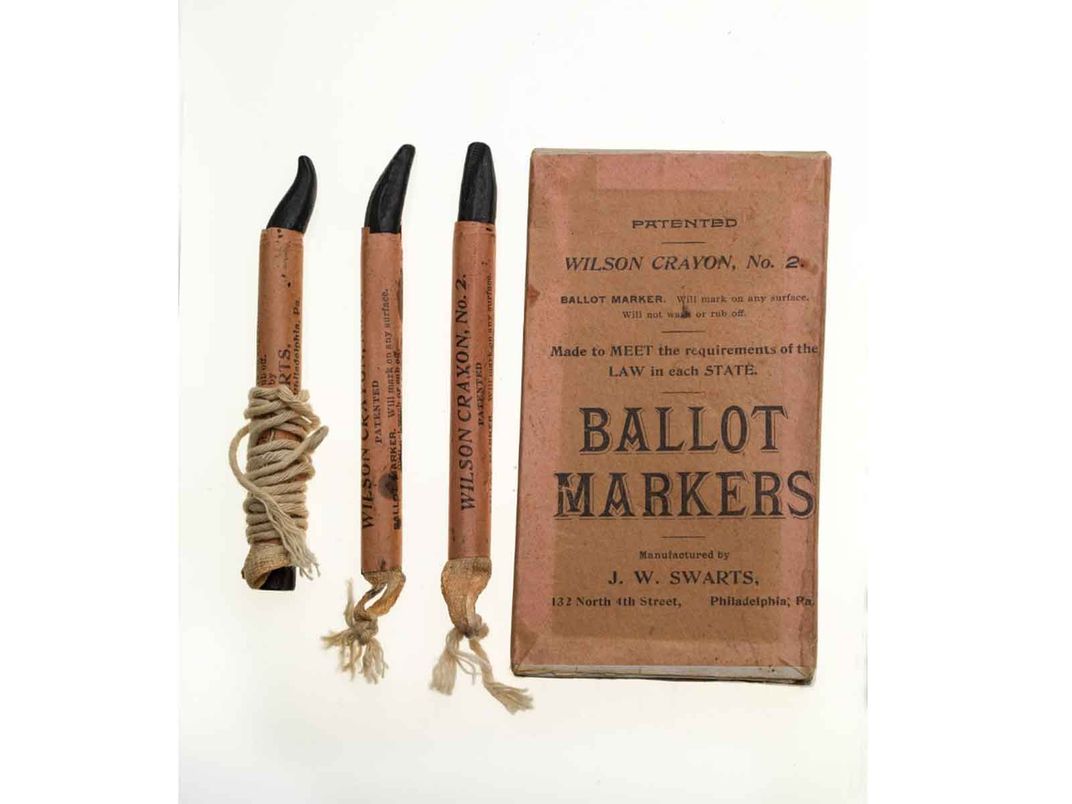

Voting itself changed in small but crucial ways. Starting in 1887, state after state switched to the secret ballot—a dense government form that was cast privately—and dispatched with party-printed tickets. By isolating each voter “alone with his conscience” in the polling booth, or behind a voting machine’s curtain, he was certainly made more reflective, but also more removed. Those who could not read English, who had previously voted by color-coded ballots, were out of luck with the complicated machines, text-heavy ballots or unsympathetic poll workers. And those who participated in Election Day because they enjoyed the day as a nationwide happening, with its the sense of community and membership, saw little appeal with the new confessional box style.

Predictably, turnout crashed. In the 1896 presidential election, 80 percent of eligible Americans were still voting, but by 1924, voter participation plummeted to fewer than 49 percent. Voters who were poorer, younger, less well-educated, African American, or immigrants or children of immigrants were especially shut out of the political arena. White, middle class Americans cheered the trend, with some even bragging about the low turnouts. “It was gratifying,” reported an Augusta, Georgia, newspaper in 1904 “to see voting booths free of noisy crowds.”

The revolution lasted for a century. What Americans now consider “normal politics” was really stifled Democracy, the post-intervention cool, calm model—lower drama but lower participation. Now, however, those old tendencies may be creeping back.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Americans flooded newspapers, magazines, clubs and street corners with a public debate over America’s chief values. A similar moment is emerging today, with a public more self-aware and reflective about democracy than during apathetic eras. Tribalism, division and “general cussedness” (as they used to call it) is up, but so is attention and turnout. The two might go hand-in-hand; the 2020 election was the first since 1900 to boast turnouts above 66 percent. “The most hopeful sign of the times,” as William Allen White reminded anxious readers in 1910, “is that we are beginning to get a national sense of our ailment.” The first step towards recovery is admitting that we have a problem.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/5a/155a3c3b-8943-42ca-806a-01941362a4c0/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/b0/02b07c25-454f-4de2-877c-776a738f322a/longform_desktop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)