The Entertaining Saga of the Worst Crook in Colonial America

Stephen Burroughs was a thief, a counterfeiter and a convicted criminal. A rare piece of his fake currency is in the collections

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/64/5b64d0ca-c358-4411-951a-60dbbe7f62c1/p24counterfeitbilljn20143518web.jpg)

For every hero in American history, there must be a hundred scoundrels—con men, Ponzi schemers, cat burglars, greedy gigolos, jewel thieves, loan sharks, phony doctors, phony charities, phony preachers, body snatchers, bootleggers, blackmailers, cattle rustlers, money launderers, smash-and-grabbers, forgers, swindlers, pickpockets, flimflam artists, stickup specialists and at least one goat-gland purveyor, not to mention all the high-tech varieties made possible by the internet.

Most of these vandals have been specialists who stuck to a single line of skullduggery until they got caught, retired or died. Some liked to brag to admirers about their enterprises, and a tiny few dared to write and publish books about them; Willie Sutton, for example, the Tommy Gun-wielding "Slick Willie" who heisted some $2 million robbing banks back in the first half of the last century (when that was a lot of money), wrote Where the Money Was: The Memoirs of a Bank Robber in 1976. There was Xaviera Hollander, the Park Avenue madam whose memoir, The Happy Hooker, inspired a series of Hollywood movies and helped encourage the sexual frankness of recent decades.

Occasionally, one of these memoirists tells of diversifying, spreading out, trying this dodge if that one doesn’t work. Sutton's lesser known contemporary, Frank Abagnale, who was portrayed in the movie Catch Me If You Can, wrote of bilking wealthy innocents of some $2.5 million by posing as a lawyer, teacher, doctor and airline pilot before going straight. Other such confessors are hiding in the archives.

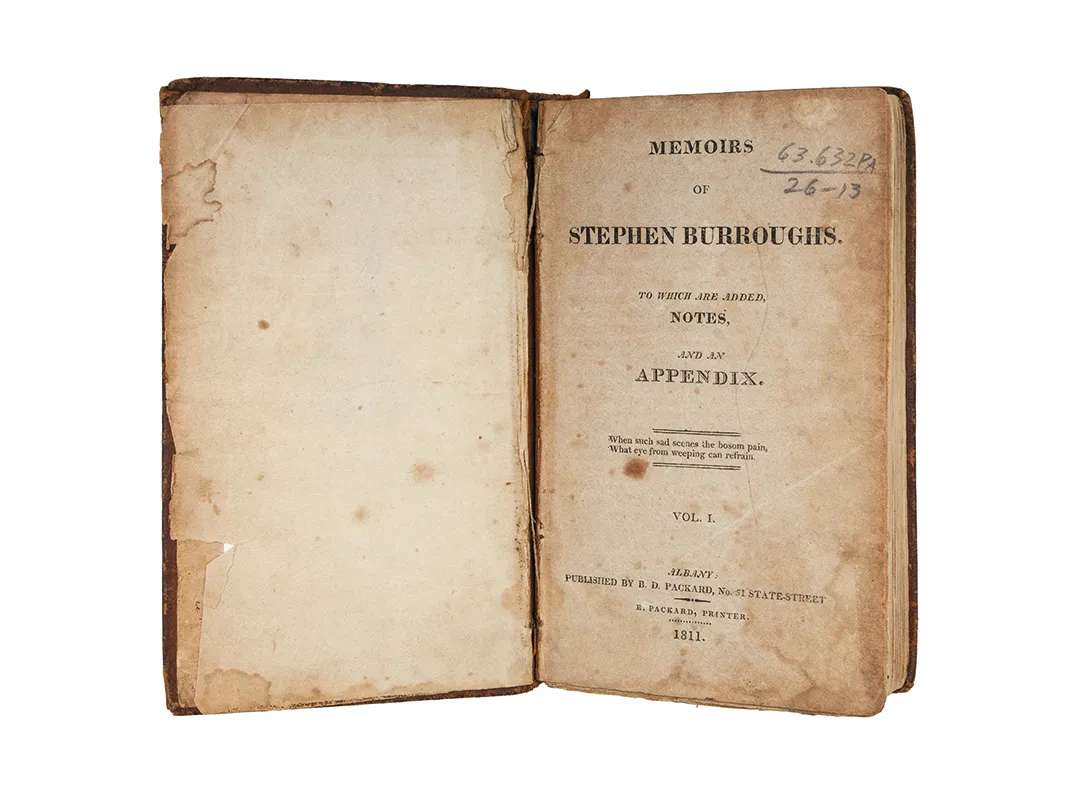

But there has been only one Stephen Burroughs, a poseur whose life would make a fabulous movie if today’s audiences were as interested in early American history as in robotic space monsters. His exploits began during the Revolutionary War when he ran off to join—then depart—the Continental Army three times at the age of 14. By the time he was 33, he had lived and misbehaved vigorously enough to make up the first version of his autobiography. So far, Memoirs of the Notorious Stephen Burroughs false has been published with slightly differing titles in more than 30 editions over a span of more than 216 years.

The New England poet Robert Frost wrote that Burroughs's book should stand on the shelf beside the autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. To Frost, Franklin's volume was "a reminder of what we have been as a young nation," while Burroughs "comes in reassuringly when there is a question of our not unprincipled wickedness…sophisticated wickedness, the kind that knows its grounds and can twinkle…Could we have been expected to produce so fine a flower in a pioneer state?"

“Sophisticated wickedness that can twinkle” sounds like a review of one of Shakespeare’s greatest hits, his sublime caricatures of English nobility. But in Burroughs we find no nobility, only 378 or so flowing pages by the only son of a harsh Presbyterian preacher in a colonial New England village; a memoirist who lived his adventures before he wrote about them with such jolly sophistication. Or at least he said he did.

Stephen Burroughs was born in 1765 in Connecticut, and moved as a child to Hanover, New Hampshire. At home and briefly away at school, he earned and proudly wore a reputation as an incorrigible child, stealing watermelons, upsetting outhouses, restlessly looking for trouble.

He explained his boyhood thus: “My thirst for amusement was insatiable…I sought it in pestering others…I became the terror of the people where I lived, and all were very unanimous in declaring that Stephen Burroughs was the worst boy in town; and those who could get him whipt were most worthy of esteem…however, the repeated application of this birchen medicine never cured my pursuit of fun.”

Indeed, that attitude explained most of Burroughs’s imaginative career.

When he was 16, his father enrolled him at nearby Dartmouth College, but that didn’t last long—after another prank involving watermelons, he was sent home. Young Burroughs proved that schooling was not necessary for a quick-witted young man zipping between gullible New England communities so nimbly that primitive communications couldn’t keep up with him.

At 17, he decided to go to sea. Venturing to Newburyport, Massachusetts, he went aboard a privateer, a private vessel authorized to prey on enemy shipping. Having no pertinent skills, he picked the brain of an elderly medicine man before talking himself aboard as the ship’s doctor. This produced a dramatic account of surgery amid storms, battling a British gunship and later being jailed for improperly issuing wine to the crew, a series of adventures that would strain even Horatio Hornblower.

The historian Larry Cebula recalls two unacquainted travelers sharing a coach in 1790 New England when one of them, a Boston lawyer, discoursed about a famed confidence man named Burroughs. This Burroughs, he said, had “led a course of the most barefaced and horrid crimes of any man living, including stealing, counterfeiting, robbing and adultery, escaping prison, burning the prison and killing guards.” He did not realize that the fellow listening quietly to all this was Stephen Burroughs himself, who by then, at the age of 25, had a log of misdeeds stretching well beyond the lawyer’s account.

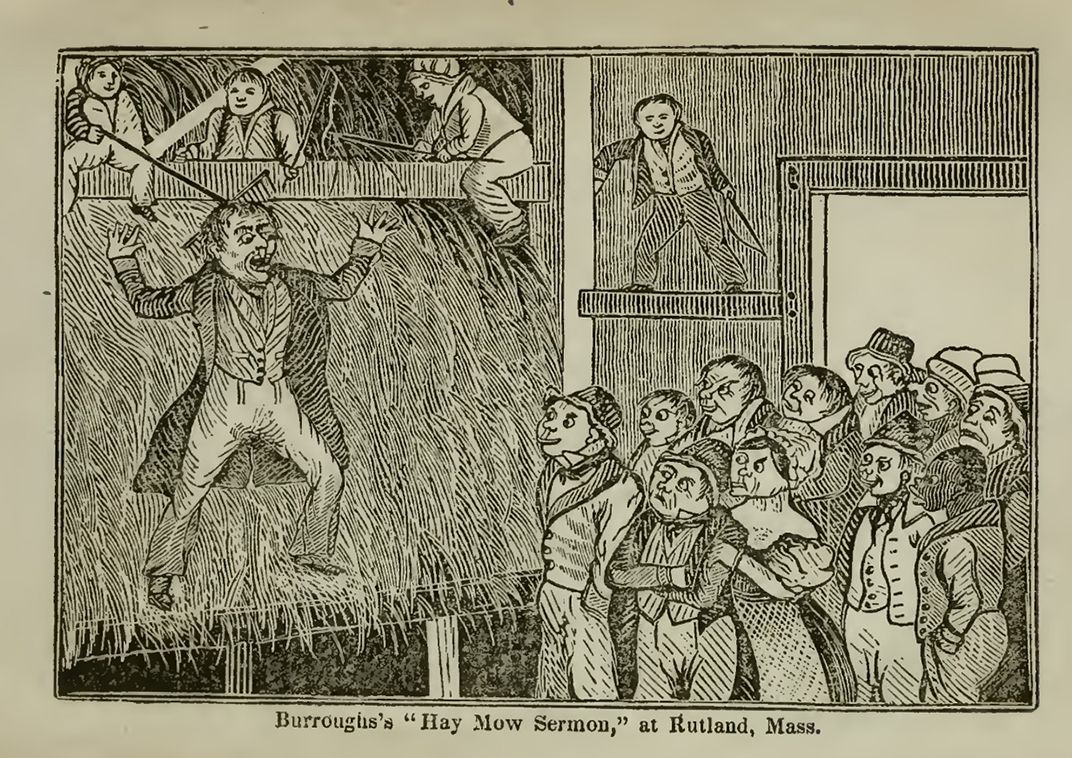

A hundred years after Burroughs first tried to become a boy soldier, Harper’s Magazine described him as “a gentleman who at times came in somewhat violent contact with the laws of his country.” Yes: after his seafaring adventure, he snitched some of his father’s sermons and headed out pretending to be a preacher; he got away with it until the congregation caught on and chased him out of town. Skipping from village to village, he briefly occupied pulpit after pulpit.

When that career dwindled, he branched into counterfeiting. Printing phony money was a popular crime in those days, before common currency was established, and Burroughs was a master. The National Museum of American History in its new exhibition American Enterprise, displays a prime example of his art—a $1 certificate on the Union Bank of Boston, dated 1807, signed by Burroughs as cashier, and later stamped COUNTERFEIT.

Artful but not quite perfect, he was caught and jailed, but broke out and moved on, becoming a schoolteacher. Convicted of seducing a teenage student, he was sentenced to the public whipping post. He escaped again and took his tutorial talents to Long Island, where he helped organize one of the nation’s first public libraries. After failing at land speculation in Georgia, he returned north and settled across the border in Quebec, nominally a farmer but still counterfeiting till he was caught and convicted yet again. But there he settled down, converting to Catholicism and living as a mostly respectable citizen until he died in 1840.

This race through some of the high/low spots of Burroughs’s life can barely hint at the richness of his memoirs, which scholars accept as mostly, or at least partly, true. Whatever their factual percentage, they remain an affectionate, sometimes hilarious, extremely readable meander voyage through provincial life in the brand-new republic.

The permanent exhibition “American Enterprise” opened on July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and traces the development of the United States from a small dependent agricultural nation to one of the world's largest economies.

American Enterprise: A History of Business in America

Memoirs Of The Notorious Stephen Burroughs Of New Hampshire

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)