A Long-Lost Manuscript Contains a Searing Eyewitness Account of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921

An Oklahoma lawyer details the attack by hundreds of whites on the thriving black neighborhood where hundreds died 95 years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/e2/c0e2c3f2-ca2e-4c12-80d2-5b9da3bab69e/20151761001web.jpg)

The ten-page manuscript is typewritten, on yellowed legal paper, and folded in thirds. But the words, an eyewitness account of the May 31, 1921, racial massacre that destroyed what was known as Tulsa, Oklahoma’s “Black Wall Street,” are searing.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top,” wrote Buck Colbert Franklin (1879-1960).

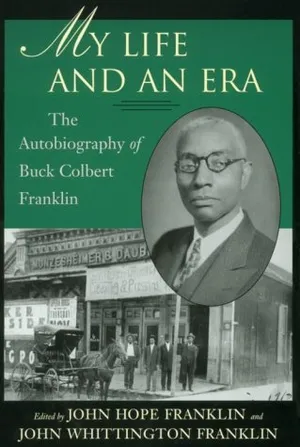

The Oklahoma lawyer, father of famed African-American historian John Hope Franklin (1915-2009), was describing the attack by hundreds of whites on the thriving black neighborhood known as Greenwood in the booming oil town. “Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.”

Franklin writes that he left his law office, locked the door, and descended to the foot of the steps.

“The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top,” he continues. “I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?’”

Franklin’s harrowing manuscript now resides among the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. The previously unknown document was found last year, purchased from a private seller by a group of Tulsans and donated to the museum with the support of the Franklin family.

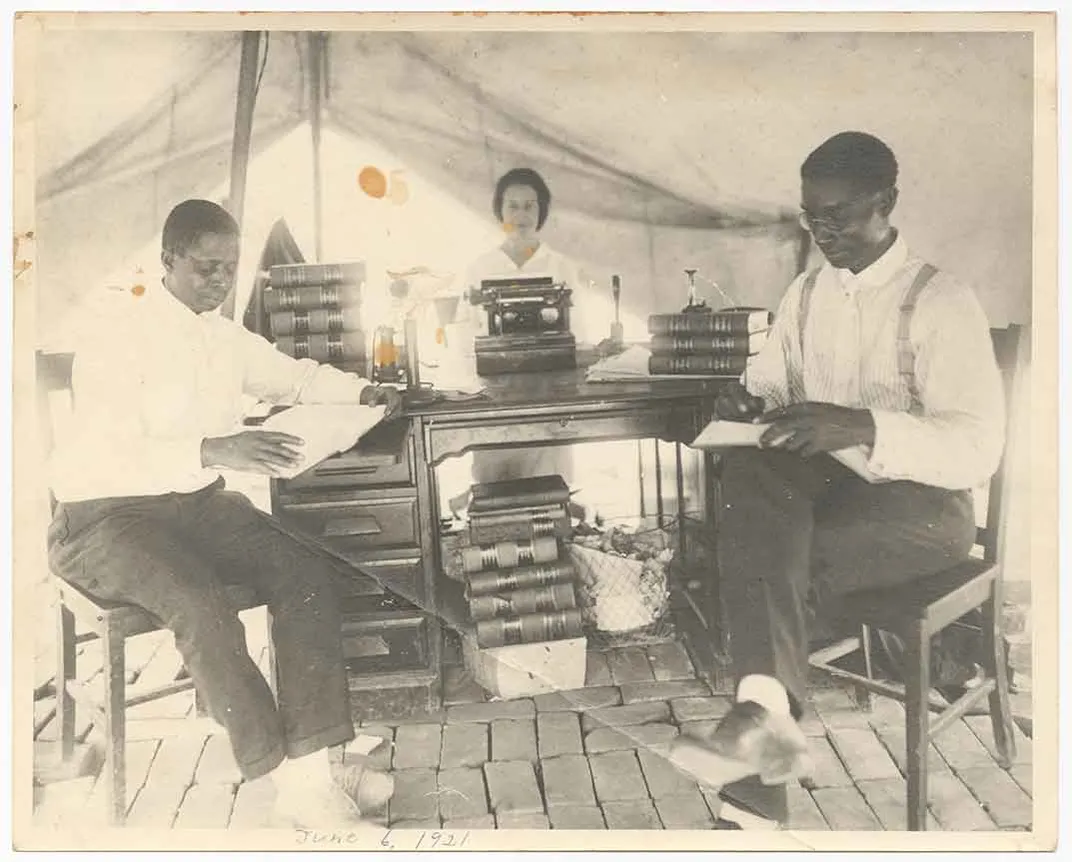

In the manuscript, Franklin tells of his encounters with an African-American veteran, named Mr. Ross. It begins in 1917, when Franklin meets Ross while recruiting young black men to fight in World War I. It picks up in 1921 with his own eyewitness account of the Tulsa race riots, and ends ten years later with the story of how Mr. Ross’s life has been destroyed by the riots. Two original photographs of Franklin were part of the donation. One depicts him operating with his associates out of a Red Cross tent five days after the riots.

John W. Franklin, a senior program manager with the museum, is the grandson of manuscript’s author and remembers the first time he read the found document.

“I wept. I just wept. It’s so beautifully written and so powerful, and he just takes you there,” Franklin marvels. “You wonder what happened to the other people. What was the emotional impact of having your community destroyed and having to flee for your lives?”

The younger Franklin says Tulsa has been in denial over the fact that people were cruel enough to bomb the black community from the air, in private planes, and that black people were machine-gunned down in the streets. The issue was economics. Franklin explains that Native Americans and African-Americans became wealthy thanks to the discovery of oil in the early 1900s on what had previously been seen as worthless land.

“That’s what leads to Greenwood being called the Black Wall Street. It had restaurants and furriers and jewelry stores and hotels,” John W. Franklin explains, “and the white mobs looted the homes and businesses before they set fire to the community. For years black women would see white women walking down the street in their jewelry and snatch it off.”

Museum curator Paul Gardullo, who has spent five years along with Franklin collecting artifacts from the riot and the aftermath, says: “It was the frustration of poor whites not knowing what to do with a successful black community, and in coalition with the city government were given permission to do what they did.”

“It’s a scenario that you see happen from place to place around our country . . . from Wilmington, Delaware, to Washington, D.C., to Chicago, and these are in some ways mass lynchings,” he says

As in other places, the Tulsa race riot started with newspaper reports that a black man had assaulted a white elevator operator. He was arrested, and Franklin says black World War I vets rushed to the courthouse to prevent a lynching.

“Then whites were deputized and handed weapons, the shooting starts and then it gets out of hand,” Franklin says. “It went on for two days until the entire black community is burned down.”

More than 35 blocks were destroyed, along with more than 1,200 homes, and some 300 people died, mostly blacks. The National Guard was called out after the governor declared martial law, and imprisoned all blacks that were not already in jail. More than 6,000 people were held, according to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, some for as long as eight days.

“(Survivors) talk about how the city was shut down in the riot,” Gardullo says. “They shut down the phone systems, the railway. . . . They wouldn’t let the Red Cross in. There was complicity between the city government and the mob. It was mob rule for two days, and the result was the complete devastation of the community.”

Gardullo adds that the formulaic stereotype about young black men raping young white women was used with great success from the end of slavery forward to the middle of the 20th century.

“It was a formula that resulted in untold numbers of lynchings across the nation,” Gardullo says. “The truth of the matter has to do with the threat that black power, black economic power, black cultural power, black success, posed to individuals and . . . the whole system of white supremacy. That’s embedded within our nation’s history.”

Franklin says he has issues with the words often used to describe the attack that decimated the black community.

“The term riot is contentious, because it assumes that black people started the violence, as they were accused of doing by whites,” Franklin says. “We increasingly use the term massacre, or I use the European term, pogrom.”

Among the artifacts Gardullo and John W. Franklin have obtained, are a handful of pennies collected off the ground from a young boy’s home burned to the ground during the riot, items with labels saying this was looted from a black church during the riot, and postcards with photos from the race riots, some showing burning corpses.

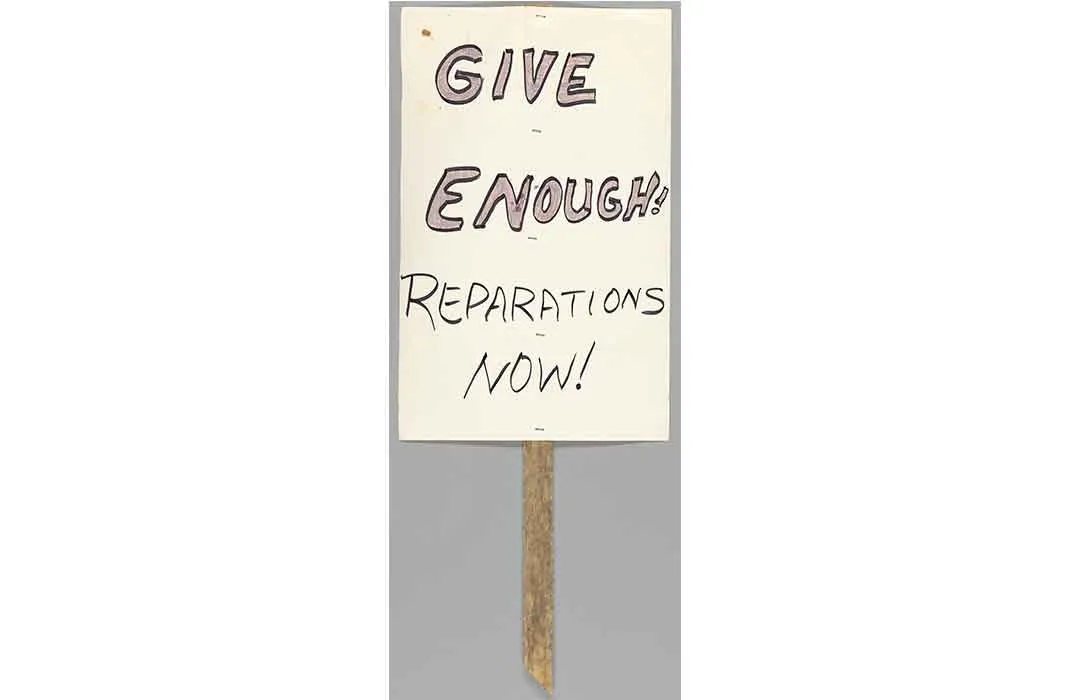

“Riot postcards were often distributed . . . crassly and cruelly . . . as a way to sell white supremacy,” Gardullo says. “At the time they were shown as documents that were shared between white community members to demonstrate their power. Later . . . they became part of the body of evidence that was used during the commission for reparation.”

In 2001, the Tulsa Race Riot Commission issued a report detailing the damage from the riots, but legislative and legal attempts to gain reparations for the survivors have failed.

The Tulsa race riots aren’t mentioned in most American history textbooks, and many people don’t know that they happened.

Curator Paul Gardullo says the crucial question is why not?

“Throughout American history there’s been a vast silence about the atrocities that were performed in the service of white history. . . . There are a lot of silences in relation to this story, and a lot of guilt and shame,” Gardullo explains. That’s one reason why the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921, will be featured in an exhibition at the new museum called “The Power of Place.” Gardullo says the title is about more than geography.

“(It’s) the power of certain places, about displacement, movement, about what place means for people,” he says. “This is about emotion and culture and memory. . . . How do you tell a story about destruction? How do you balance the fortitude and resilience of people in response to that devastation? How do you fill the silences? How do you address the silences about a story that this community has held in silence for so long and in denial for so long?”

Despite the devastation, the black community in Tulsa was able to rebuild on the ashes of its neighborhood, partly because Buck Colbert Franklin battled all the way to the Oklahoma Supreme Court to defeat a law that would have effectively prevented African-Americans from doing so. By 1925, there was again a thriving black business district. John W. Franklin says his grandfather’s manuscript is important for people to see because it deals with “suppressed history.”

“This is an eyewitness account from a reputable source about what he saw happen,” he grandson John W. Franklin says. “It is definitely relevant to today, because I think our notions of justice are based partially on our own history and our knowledge of history. But we are an a-historical society, in that we don’t know our past.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opens on September 24 of this year on the National Mall.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)