A Long Overdue Retrospective for Kay WalkingStick Dispels Native Art Stereotypes

At the American Indian Museum, the new show traces a career that included minimalist works to monumental landscapes

“I’m a talker. I have a hard time shutting up,” admits artist Kay WalkingStick as she leads a reporter through a retrospective of her works at the National Museum of the American Indian. But standing in front of a wall of charcoal and graphite sketches on paper, the 80-year-old Easton, Pennsylvania-based painter and Cherokee Nation member talks about doing the exact opposite—preserving the mystery in her art.

“What the heck is going on? Why on earth would she put a cross in the middle of all that mess?” she says people must ask about her art.

“I like the idea of people coming to it and not fully understanding it—maybe taking that home and thinking about what on earth was happening there,” she says.

Her five-decade career is honored in this first major retrospective, “Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist,” on view through Sept. 18, 2016, and includes more than 65 rarely exhibited works. Upon first seeing the installation, WalkingStick was overwhelmed. “I feel disconnected from the work somewhat, because I’ve always seen it in the studio or in a small gallery,” she says. “Much of it I haven’t seen for years.”

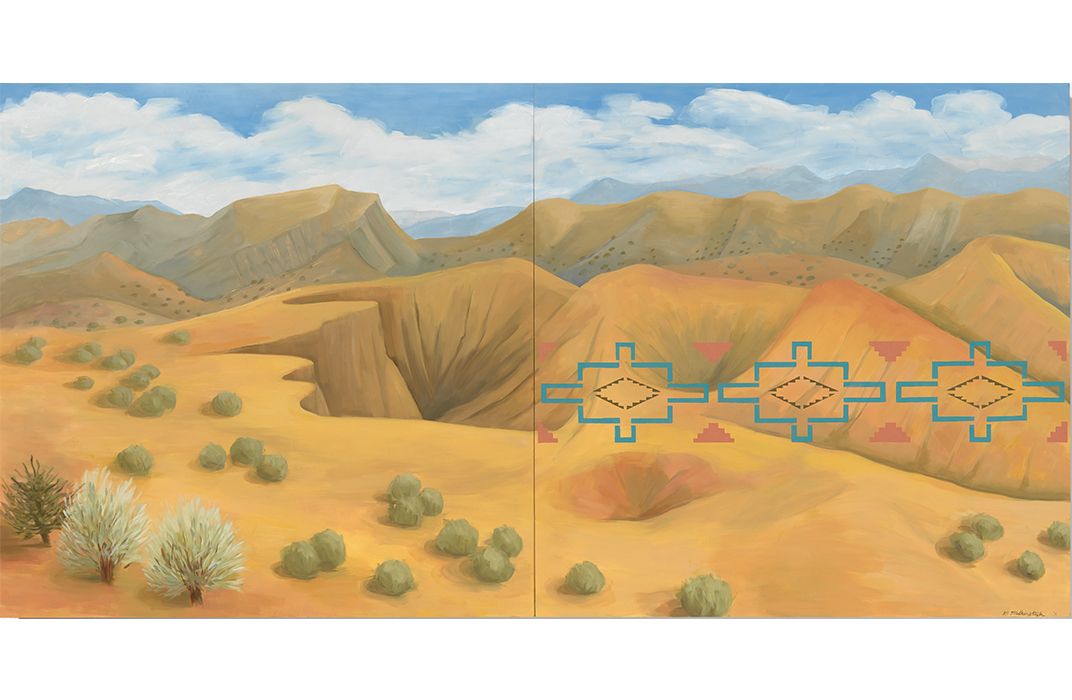

As retrospectives are wont to do, the exhibition demonstrates significant changes in WalkingStick’s repertoire. The show opens with the 2011 New Mexico Desert, a large painting from the Museum’s permanent collections that includes traditional patterns superimposed upon a desert landscape, and the exhibition traces her career from her minimalist works of the 1970s, many which depict sensual bodies—mostly nude self-portraits—to her more recent monumental landscape work.

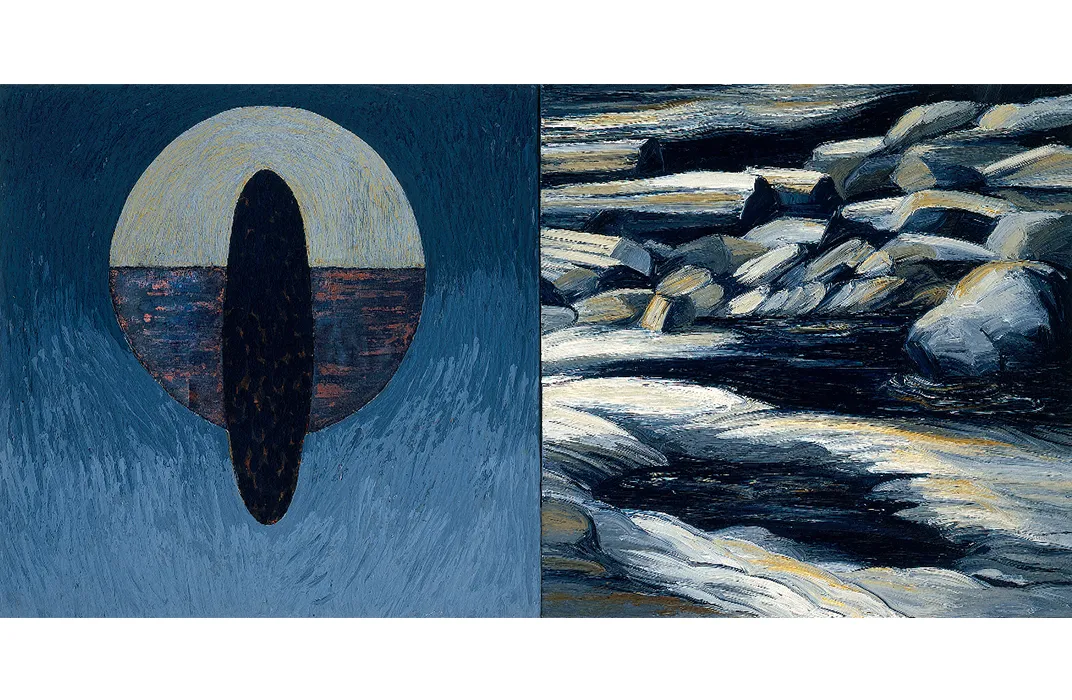

The blue skies and clouds in her 1971 Who Stole My Sky, a series of stacked canvases inside a wood frame that resembles a box-within-a-box construction, is evocative of René Magritte’s 1928 The False Mirror. Writing in the show’s catalog, Kate Morris, associate art history professor at Santa Clara University, notes that WalkingStick’s sky paintings were a response to the burgeoning environmental movement of the early 1970s. “The closest she ever came to making overt political proclamations in her early work,” Morris writes.

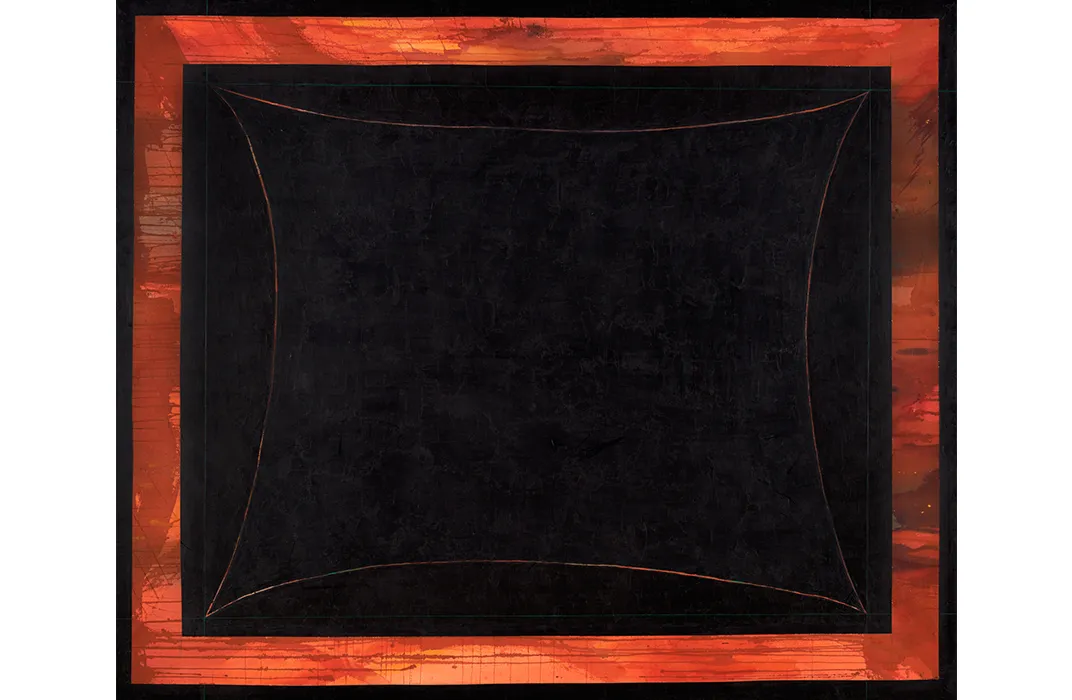

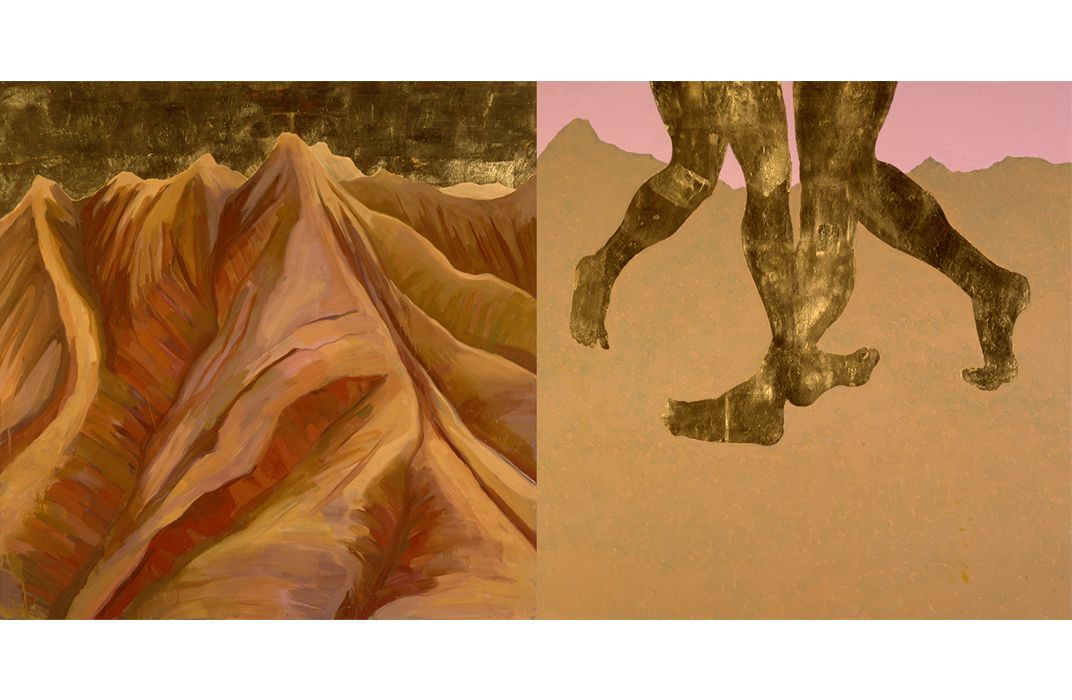

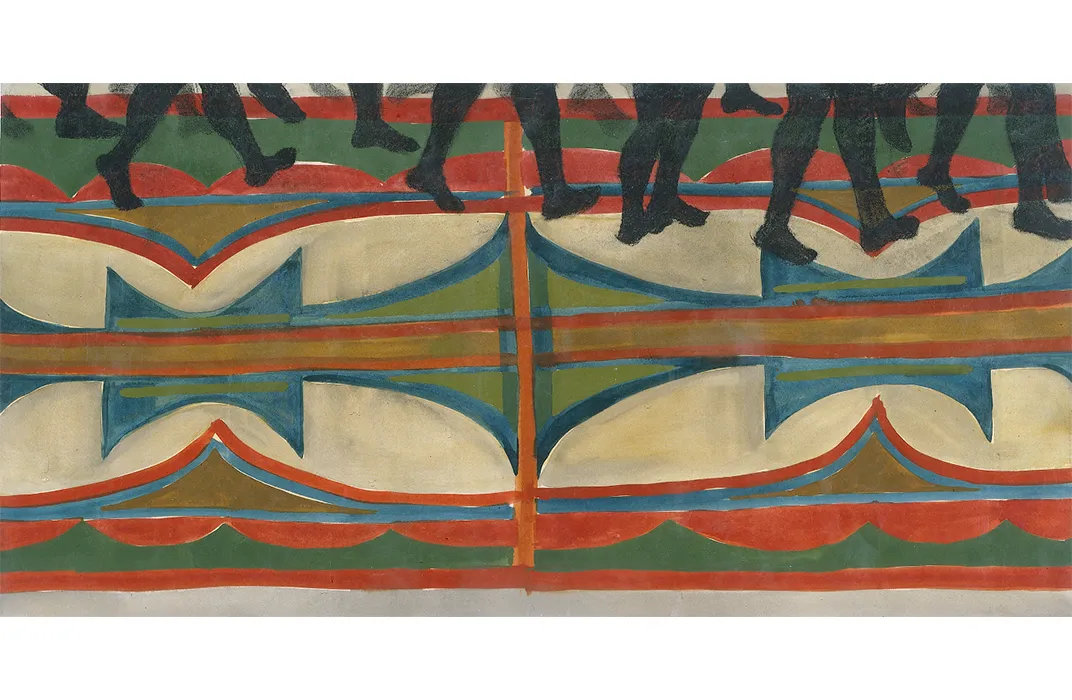

Heavily layered canvases from the 1980s with thickly applied acrylic paint and saponified wax, that embed slashes and crosses—what WalkingStick describes as “all that mess”—are followed in subsequent galleries with her diptych works that juxtapose abstraction and representational forms. Next, is a series of mappings of the body across landscapes; and finally works that combine traditional Native patterns and landscapes.

Growing up, art was the “family business” for WalkingStick. Two of WalkingStick’s uncles were professional artists; and her brother, Charles WalkingStick, 93, who lives in Oklahoma, was a commercial artist, and a sister is a ceramicist.

“Indians all think they’re artists. All Indians are artists. It’s part of the DNA,” WalkingStick says. “I grew up thinking this was a viable thing to do. I’ve always drawn.”

WalkingStick likes to tell people that she learned to draw going to the Presbyterian church. Her mother would hand her pencil and paper during the long sermons. WalkingStick remembers sitting near a rose window.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/b3/08b3c80e-80b0-4643-b66f-eeb5d7a7f575/2014juliamaloofverderosa4852web.jpg)

Her 1983-1985 Cardinal Points from the collection of Phoenix’s Heard Museum is in the exhibition and blends the four-directional cross, the compass directions, and the coloration of the male cardinal (the bird) and of Catholic cardinals. “There’s this double meaning to the title,” WalkingStick says.

She used her hands to spread the acrylic paint and saponified wax on the canvas, and glued a second layer of canvas upon the first. (She gouged the cross out with a woodcutter’s tool after the paint dried, “so that you get a nice sharp line. If you did it while it was wet, you’d get a smooshy line.”) The work, she estimates, has about 30 coats of paint. The wax—composed the way soap is made—“takes away the plastic look of the paint itself,” he says. “It gives it a more natural look. It also happens to make the studio smell divine. It’s made with beeswax; it smells like honey.”

All of those layers make the canvases—whose size she selected based on her arm span so that she could lift them—quite heavy. WalkingStick typically lays the canvas flat on a table while she works, but she still had to move them when they were done.

“I’m a big strong girl,” the octogenarian says. “I think back, how the heck did I do that? I can still carry them, but I can’t sling them around like I used to.”

The exhibition of WalkingStick’s works is part of a broader goal of the museum’s to expand the public’s understanding of what contemporary Native art looks like, according to co-curators Kathleen Ash-Milby and David Penney.

“Many of our visitors have a difficult time reconciling the fact that people of Native ancestry have very complicated, full, rich, often cosmopolitan lives in the later 20th, early 21st century. They’re really expecting American Indian people to be one way. It’s less than an identity and more of a cultural stereotype,” Penney says.

There are Native artists who create traditional works, and that’s a great thing, but other Native artists work in new media, performance and a variety of other areas. “And they’re still Native,” says Ash-Milby. “Some of our best artists do have Native content in their work, but it’s more sophisticated.”

Penney notes that WalkingStick’s recent landscapes draw upon American landscape traditions, such as those of 19th-century Hudson River School artist Albert Bierstadt.

“The message of those big Bierstadts was really: here is a wilderness continent ready for conquest. In a sense these pictures are an attempt to reclaim that landscape,” Penney says of WalkingStick’s work. “Geology is witness to cultural memory. And then these designs are a way of reasserting the fact that these are Native places that can’t be separated from Native experience, history, and the history of this country.”

Asked what she hopes viewers will take away from the show, WalkingStick echoes similar goals. “I would like people to understand on a very profound level that Native people are part and parcel of our functioning world, our whole world, our nation. That we are here. That we are productive. And that we are speaking to others,” she says. “We are part of the mainstream culture.”

"Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist" is on view through Sept. 18, 2016 at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. The American Federation of the Arts will tour the exhibition to the Dayton Art Institute in Dayton, Ohio (Feb. 9, 2017–May 7, 2017), Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, N.J. (Feb. 3, 2018–June 17, 2018) and two additional venues in 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)