Long Sidelined, Native Artists Finally Receive Their Due

At the American Indian Museum in NYC, curators paint eight decades of American Indian artwork back into the picture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/88/e1/88e1b187-0e2a-444b-88ac-e426362cd16d/mario_martinez_brooklyn.jpg)

Museums are beginning to rewrite the story they tell about American art, and this time, they’re including the original Americans. Traditionally, Native American art and artifacts have been exhibited alongside African and Pacific Islands art, or in an anthropology department, or even in a natural history wing, “next to the mammoths and the dinosaurs,” says Paul Chaat Smith, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). But that has begun to change in recent years, he says, with “everyone understanding that this doesn’t really make sense.

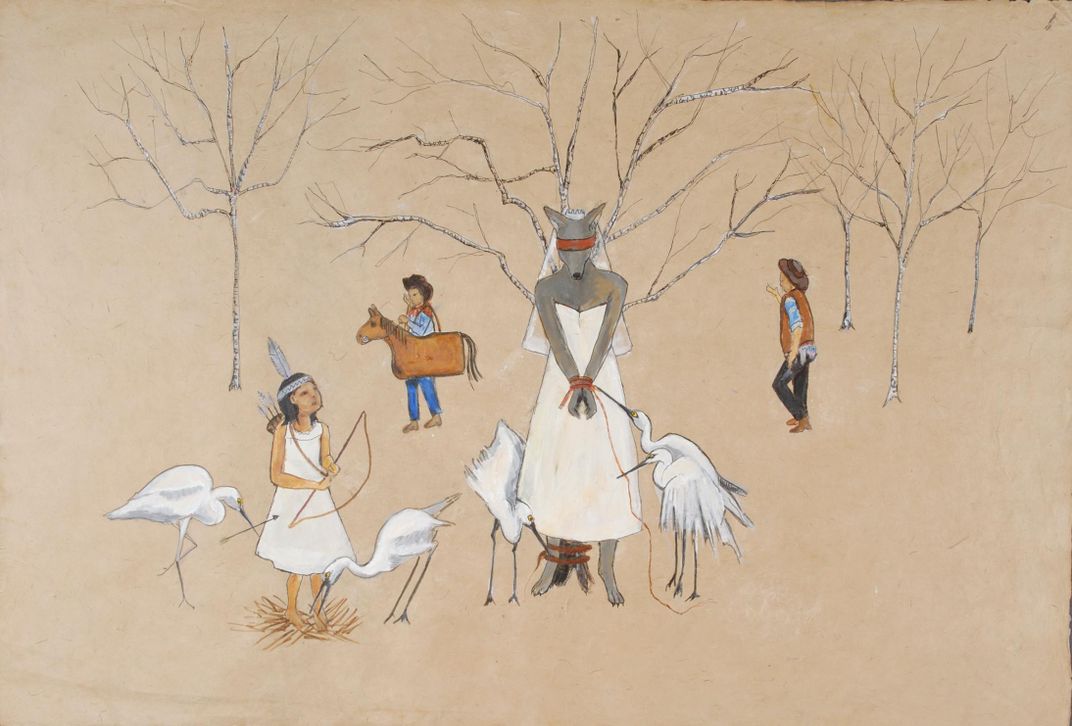

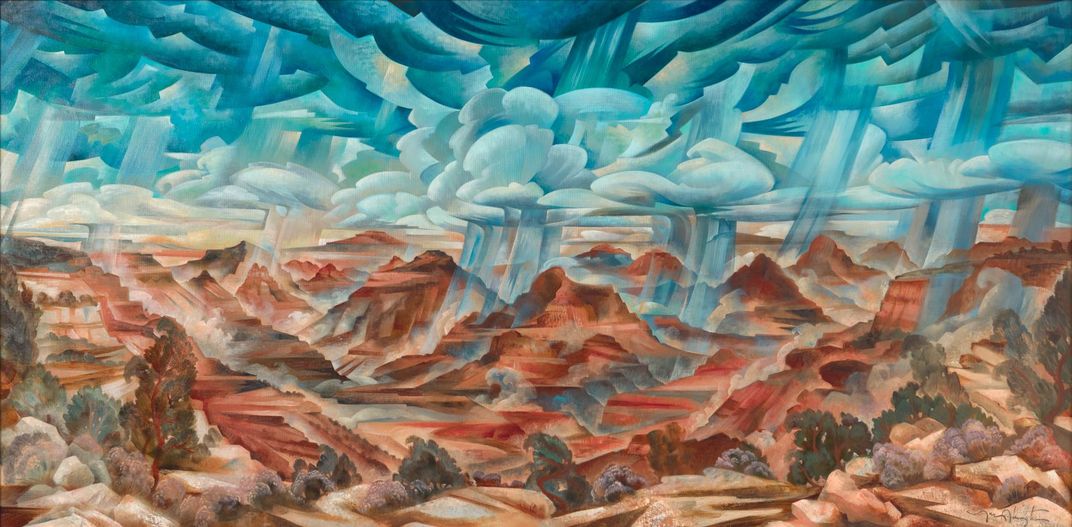

Smith is one of the curators of “Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting,” a new exhibition at the NMAI’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. The show pushes to the foreground questions of where Native American art—and Native American artists—truly belong. The paintings, all from the museum’s own collection, range from the flat, illustrative works of Stephen Mopope and Woody Crumbo in the 1920s and ’30s to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s politically current Trade Canoe, Adrift from 2015, depicting a canoe overloaded with Syrian refugees. Some paintings include identifiably Native American imagery, others don’t. But almost all reveal their artists as deeply engaged with non-Native art, past and present. The artists reflect, absorb and repurpose their knowledge of American and European art movements, from Renaissance painting to Modernist abstraction and Pop.

“American Indian artists, American Indians generally speaking, were sort of positioned in the United States as a separate, segregated area of activity,” says the museum’s David Penney, another of the show’s curators. In “Stretching the Canvas,” he and his colleagues hope to show “how this community of artists is really part of the fabric of American art since the mid-20th century.”

The show opens with a room of blockbusters, a group of paintings the curators believe would hold their own on the walls of any major museum. They state the case with powerful works by Fritz Scholder, Kay WalkingStick, James Lavadour and others.

For decades, Native American art wasn’t just overlooked; it was intentionally isolated from the rest of the art world. In the first half of the 20th century, government-run schools, philanthropists and others who supported American Indian art often saw it as a path to economic self-sufficiency for the artists, and that meant preserving a traditional style—traditional at least as defined by non-Natives. At one school, for example, American Indian art students were forbidden to look at non-Indian art or even mingle with non-Indian students.

In painting in particular, Indian artists of the ’20s, ’30s and beyond were often confined to illustrations of Indians in a flat, two-dimensional style, which were easy to reproduce and sell. Native artists were also restricted in where they could exhibit their work, with just a few museums and shows open to them, which presented almost exclusively Native art.

The doors began to crack open in the ’60s and ’70s, and art education for American Indians broadened. Mario Martinez, who has two large and dynamic abstract paintings in the exhibition, cites Kandinsky and de Kooning among his major influences. He was introduced to European art history by his high school art teacher in the late ’60s, and never looked back.

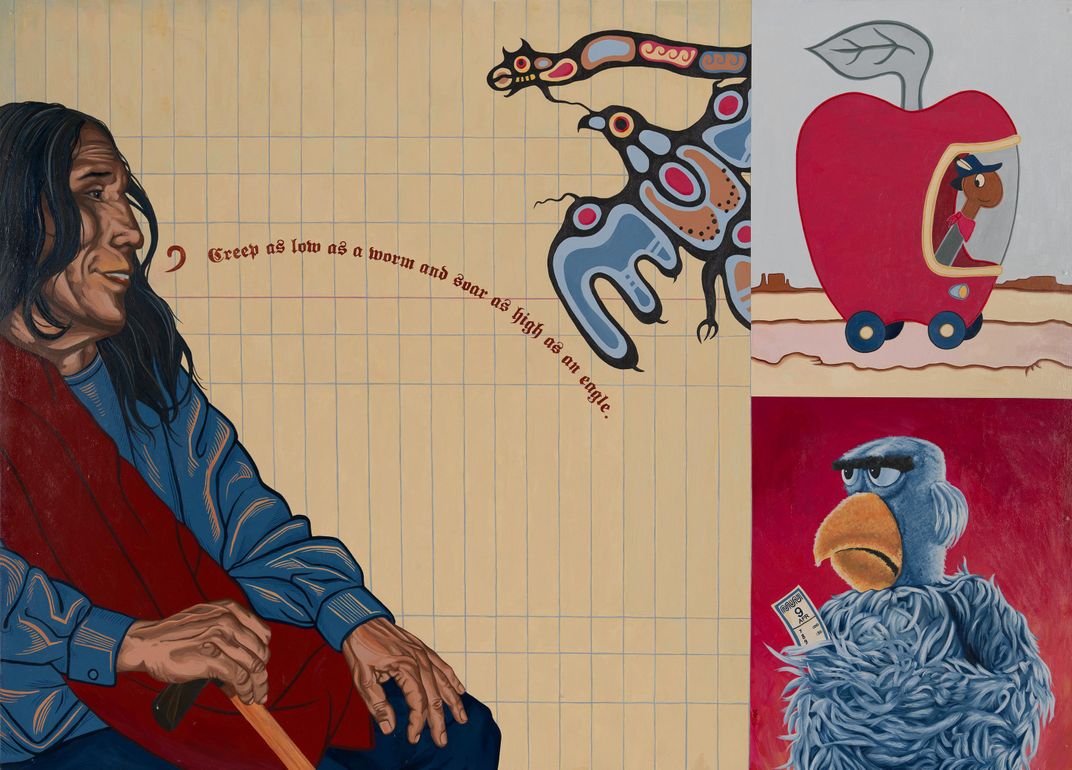

Yet even now, another artist in the show, America Meredith, senses a divide between Native Americans’ art and the contemporary art world as a whole. She talks about the challenge of overcoming “resistance” from non-Native viewers. “When they see Native imagery, there’s kind of a conceptual wall that closes: ‘Oh, this isn’t for me, I’m not going to look at this,’” she says. So American Indian artists have to “entice a viewer in: ‘Come on, come on, hold my hand, look at this imagery,’” she says with a smile. Meredith’s work in the show, Benediction: John Fire Lame Deer, a portrait of a Lakota holy man, mashes up visual references to European medieval icons, the children’s book illustrator Richard Scarry, Native American Woodland style art and the Muppets. “I definitely use cartoons to entice people,” she says. “People feel safe, comfortable.”

Penney says the exhibition comes at a moment when “major museums are beginning to think about how American Indian art fits into a larger narrative of American art history.” Nine years ago the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston opened a new Art of the Americas wing that integrated Native American work with the rest of its American collections; more recently, an exhibition there put the museum’s own history of acquiring Native art under a critical microscope.

In New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art currently has a show of multimedia work by the Mohawk artist Alan Michelson, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year for the first time began displaying some Native American art inside its American wing (instead of with African and Oceanic arts elsewhere in the building). Later this month the Met will unveil two paintings commissioned from the Cree artist Kent Monkman. The art world as a whole, says Kathleen Ash-Milby, curator of Native American art at the Portland Art Museum, who also worked on “Stretching the Canvas,” is “reassessing what is American art.”

As an example, Paul Chaat Smith points to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, who has been working for decades but is getting new attention at age 79. “Not because her work is different,” he says. “Because people are now able to be interested in Native artists.”

“Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting” is on view at the National Museum of the American Indian, George Gustav Heye Center, One Bowling Green, New York, New York, until autumn 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SusannahGardiner.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SusannahGardiner.JPG)