Lonnie Bunch Sizes Up His Past and Future at the Smithsonian

Bunch’s new memoir details the tireless work it took to build NMAAHC and offers insights into his priorities as Smithsonian Secretary

:focal(925x361:926x362)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/78/07781454-6e91-47f5-9aba-6caa5e2a5e16/lonniecovercrop.jpg)

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is a historical and cultural nexus where American life bears its complex, painful and often self-contradictory soul. NMAAHC is built on fascinating dualities: celebrating African-American history, yet bearing witness to its greatest tragedies; exhibiting objects from everyday homes, yet contextualizing them with academic rigor; acknowledging America’s promises, yet making clear its failures to live up to them; offering an oasis of peace and coming-together, yet reminding all who enter of the deep rifts that still divide us. It is a museum that argues compellingly that the African-American story is the American story.

Walking these various ideological tightropes was the constant honor and burden of Lonnie Bunch, the museum’s founding director, who signed on to the project in 2005 and fought tooth and nail to make what had for a century been a strictly conceptual museum a tangible, physical, beautiful place of learning with a prominent spot on America’s National Mall. Bunch presided over the groundbreaking ceremony in 2012 and the museum’s triumphant opening in 2016.

For more than ten years nonstop in his career as a historian and educator, Bunch lived and breathed the African American History Museum. Now he is beginning a new chapter, leaving the museum he shepherded in capable hands and assuming the position of Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, where he will oversee the entirety of Smithsonian operations using his hard-won success at NMAAHC as a template for bold new initiatives.

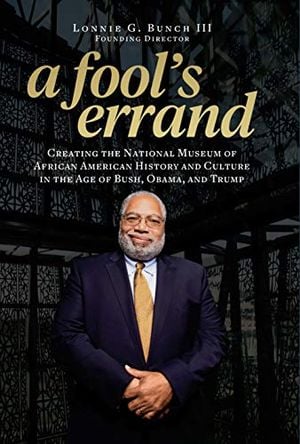

Bunch’s memoir of his time fighting to bring NMAAHC to fruition, titled A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump, comes out this Tuesday, September 24, offering an in-depth look at Bunch’s vision for NMAAHC and providing hints at his vision for the Smithsonian Institution as a whole moving forward.

Though painstaking in its detail, A Fool’s Errand is far from a dry memoir. Bunch’s recollections of one scrappy victory after another—securing funding, mustering staff, icing prime real estate on the National Mall, unearthing artifacts across the country—are so tense and laden with drama that the book often reads more like the plot of a crowd-pleasing underdog boxing movie than a ho-hum institutional history. The narrative and frequently humorous quality of Bunch’s writing is no accident, as he modeled his work on Langston Hughes’s Not Without Laughter, which Bunch said in a recent interview taught him to “capture a period, but contextualize it through my own personal lens.”

He hopes these personal touches will make the book more accessible to those looking for guidance with their own efforts in the museum field and will give his daughters and grandchildren an approachable and poignant look at one of the most important segments of his life. “Someday,” Bunch says, “they may be interested in this 11-year period, and I couldn’t explain or tell them all the stories. So I thought putting them in the book would be great.”

Bunch found the process of methodically looking back on building NMAAHC revelatory. The magnitude of what he and his team had been able to accomplish was something he could never fully appreciate during the whirlwind of activity itself. “I can’t believe we pulled it off!” he says. “I literally thought, ‘Are you kidding me? We went through all of that?’ It was almost frightening.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/4c/824ceed8-4fba-4fa5-baf8-6eda4adc25dd/2017_30_47_001crop.jpg)

A Fool’s Errand details several instances of anxiety and self-doubt for Bunch in the museum’s long march to success, including demoralizing meetings with potential donors and a near-catastrophic run-in with D.C.’s water table as the museum’s subterranean exhibition spaces expanded downward into the earth. One incident that Bunch says particularly shook him was a freak accident that claimed the life of a construction worker at a time when everything seemed to be coming together. “I never wanted anybody to sacrifice for this museum, and here I felt this man gave his life,” Bunch recalls. Ultimately, though, Bunch says the tragedy spurred him and his team to redouble their efforts to make NMAAHC real. “It convinced me that we would pull this off,” he says, “and that we would honor not just him, but everyone else who lost lives and suffered in the struggle to find fairness.”

One key aspect of pulling off a museum of this scope was conjuring collections of artifacts to serve as the basis for exhibitions—collections which simply did not exist when Bunch took the job of founding director. Among other ambitious expeditions, Bunch remembers traveling personally to Mozambique Island off the southeastern coast of Africa with the support of the Slave Wrecks Project in search of a better understanding of the slave trade and the remains of a Portuguese slave ship sunken near Cape Town, South Africa—a portion of which Bunch got to bring back to Washington for the museum. “A young woman came up to me and told me that her ancestor was on that boat and died, and that she thinks of him every day,” Bunch says. “It reminded me that even though I saw this as the past, it really was the present to so many.”

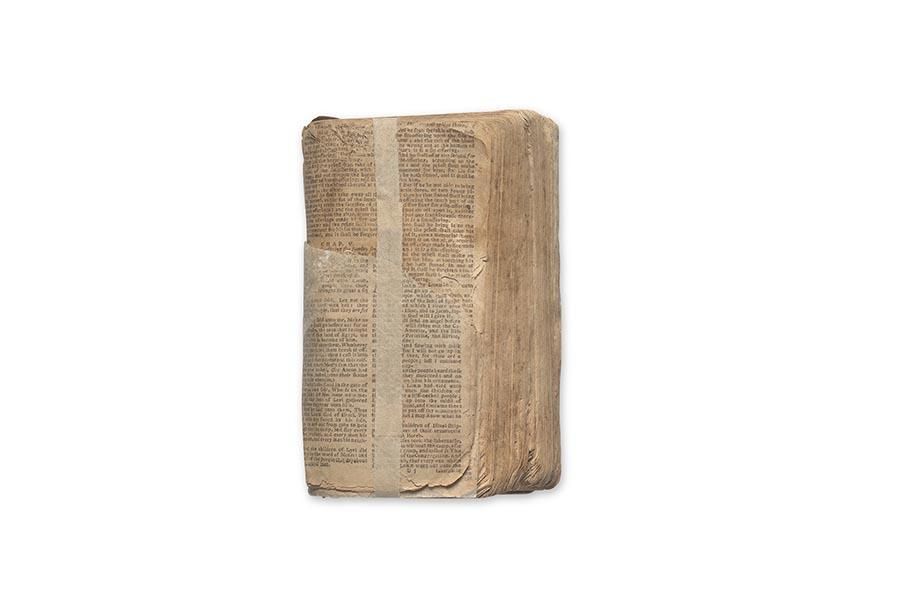

In the end, a staggering 70 percent or so of the items in NMAAHC’s collections wound up coming from the homes of families strewn across the U.S.—a testament to the museum’s emphasis on community and representation. In A Fool’s Errand, Bunch writes of his shock at the emergence of such artifacts as a photo album containing a never-before-seen image of young Harriett Tubman and a Bible that once belonged to abolitionist rebel Nat Turner. “I knew there were things out there,” Bunch says, “but I didn’t realize the depth or extensiveness, and how much people would trust us to give us that material.”

The dream of NMAAHC crystallized with an emotional opening ceremony in September of 2016, where Bunch recalls President Barack Obama asserted eloquently the need for a national African-American museum. To mark the historic moment, Ruth Odom Bonner, a woman whose father had been born enslaved in Mississippi, rang the deeply symbolic Freedom Bell with three generations of family gathered around her.

Bunch says the importance of NMAAHC as a beacon for African-Americans across the country was never clearer to him than when an elderly woman recognized him on 16th Street mid-power walk one day and stopped him for a heartfelt hug. “She simply said, ‘Thank you for doing something nobody believed in. Thank you for giving my culture a home.’ That just meant the world to me.”

Though understandably bittersweet about leaving NMAAHC in the hands of his colleagues to assume the overarching role of Secretary of the Smithsonian, Bunch is ultimately very excited to make use of the lessons he learned there and bring his dynamic brand of leadership to bear as overseer of the Smithsonian Institution at large. And while he recognizes that he won’t be able to shape every last detail of the Institution like he did at NMAAHC, Bunch seems self-assured about his ability to leave a mark on the position and improve the Smithsonian collaboratively in the years ahead. “They didn’t hire me simply to manage, they hired me to lead,” he says. He likens the balance of delegation and direct input to a pilot’s decision to use autopilot vs. flying manually. “There are times when you need it on autopilot,” he explains, “but there are other times when you actually need to bank it left or right.”

A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump

Founding Director Lonnie Bunch's deeply personal tale of the triumphs and challenges of bringing the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture to life. His story is by turns inspiring, funny, frustrating, quixotic, bittersweet, and above all, a compelling read.

It’s no secret that political entrenchment and animosity is running high in America, but Bunch maintains that the Smithsonian is committed to truth and nuance in historical and cultural scholarship, not political agendas. “What the country needs are places that are nonpartisan and safe, where people can grapple with what’s going on around them,” he says. “Regardless of political challenges, we will always be that great educator—one that will sometimes confirm what people think, sometimes confront their notions, and help them remember who they once were and who they could become.”

What are Bunch’s plans to carry the Smithsonian forward into a new era? He admits he’s still figuring that out, but at the core of his philosophy lies an emphasis on technology and community engagement via innovative new avenues. “As museums do new exhibitions and refurbish old ones,” he says, “I’d like to see them do a better job of understanding their audience.” In terms of tech, he says this might mean moving away from digitization for digitization’s sake and focusing instead on user-friendly online interfaces where everyday people, rather than niche academic circles, can engage meaningfully with the collections of the Smithsonian. “I do not want us to become a kind of intellectual think tank,” he says, “but rather a place where the work of intellectuals, scholars and educators is made accessible and meaningful to the American public.”

One early illustration of this public-minded vision for the Smithsonian was Bunch’s insistence that the Smithsonian support the New York Times’ 1619 Project, a moving profile of the arrival of the slave trade in colonial America 400 years ago which, in the words of the Times, set out to “reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.” Bunch worked with NMAAHC curator Mary Elliott on the museum’s contributions to the project and took pains to ensure the Smithsonian name would be publicly associated with it.

“We call ourselves the Great Convener,” Bunch says of the Smithsonian, “but really we’re a Great Legitimizer. And I want the Smithsonian to legitimize important issues, whether it’s 1619 or climate change. We help people think about what’s important, what they should debate, what they should embrace. Everybody that thought about the 1619 Project, whether they liked it or disagreed with it, saw that the Smithsonian had fingerprints on it. And that to me was a great victory.”

Bunch also firmly believes that in order for the Institution to faithfully represent the American public in the content it produces, it must first do so in the composition of its workforce. As Secretary, he hopes to give America’s disparate cultures the opportunity to tell their own stories rather than see them distorted through the lenses of those who lack direct experience. “I want the Smithsonian to make diversity and inclusion so central that it’s no longer talked about,” he says.

It’s clear the new Secretary has his work cut out for him. But as is typical of Lonnie Bunch, he’s excited, not scared, to overcome the hurdles ahead and make the Smithsonian better for America. “As we say in Chicago,” he says with a nod to his old home, “Make no small plans!”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)