Looking Back at an Early Woman Inventor: Charlotte Kramer Sachs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/char1.jpg)

What do the dishwasher, windshield wipers and ScotchGuard have in common?

Women invented them all.

Last week, as Women’s History Month came to a close, Tricia Edwards, an education specialist at the National Museum of American History’s Lemelson Center, led museum visitors back in time to take a look at those who pioneered women's role in inventing.

Men composed the majority of inventors in the 19th and 20th centuries, most often overshadowing products by women inventors. So, the earliest women inventors needed curiosity, courage and persistence to claim ownership of their work (let alone earn a profit from it.) Through the early 20th century, only one percent of U.S. patents granted annually were given to a woman.

One of them was Charlotte Kramer Sachs (1907-2004), a native of Germany. After marriage, the birth of her daughter Eleanor, and a divorce, Sachs struck out on her own, moving between London and New York City and creating her own publishing company, called the Craumbruck Press. She never attended a university, but her natural curiosity made her a master of music, poetry, art and four different languages, Edwards said.

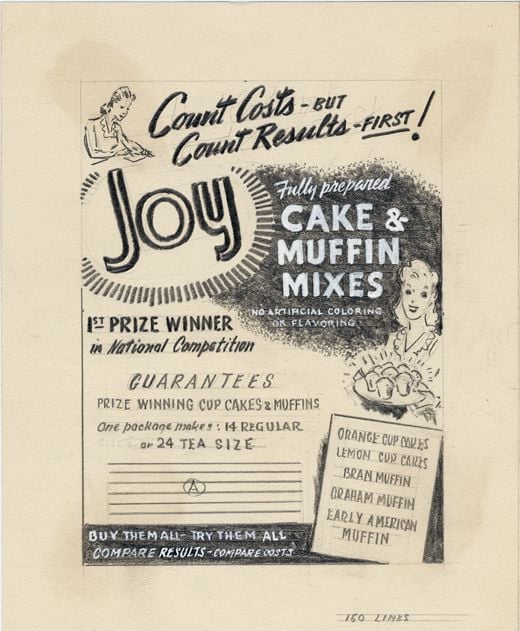

It also gave her a knack for taking household items and making them even more useful. In 1940, she received her first patent: Improvements in Combined Key and Flashlight, a device that attached a light to the end of keys. That same year, inspired by classes she took at the New York Institute of Dietetics to learn how to better care for her diabetic daughter, she also launched what Edwards believes is the first line of prepared baking mixes: Joy Products.

After trial and error in her kitchen, and several taste tests by friends and neighbors (whose early feedback included “too much soda” and “would not buy for 25 cents"), Sachs took the operation to a small Bronx factory, where 90 workers produced the line’s earliest packages of corn muffins and popover mixes. It was a success, and the product soon expanded to include breads, cakes, frosting and puddings.

In 1945, she married again, this time to Alexander Sachs, an adviser to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt who introduced the president to Albert Einstein. (Whether or not this inspired Sachs is unknown). The 1950s were spent on a number of convenience items, including the “Gui-dog,” one of the earliest versions of the retractable dog leash, and “Watch-Dog,” a dog collar with a time piece to keep track of time while out walking the dog (not all of her ideas came to fruition).

But most will probably recognize Sachs, Edwards says, as the early inventor of the “The “Modern Wine Cellar.” In 1966, she came up with a storage device that kept wine at the appropriate temperature, and then expanded that idea to include storage cabinets for instruments, cigars and documents, and invented several wine accessories, including the wine bib, which catches drops of wine that may fall while pouring a bottle (and, simultaneously, saves that nice white tablecloth).

“She really excelled in consumer convenience products,” Edwards said.

The storage cellars fueled the rest of her career. Sachs continued to work in her office with the help of one or two assistants until the day before she died in 2004—at the age of 96.

It seems Sachs' influence, along with the influence of other women inventors, has paid off: the number of U.S. patents granted to women has grown to more than 12 percent (according to the latest data taken by the U.S. Patent Office, in 1998) and likely even more than that today.

Sachs was only one of many successful early women inventors. To learn more about others, visit the Lemelson Center’s Inventors Stories page.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)