We’re Looking for the Best Rock ‘n’ Roll Photos. What’s in Your Collection?

For those who photograph rock, we salute you

From the beginning, rock ‘n’ roll’s visuals often played as loud as the music.

Television and film chronicled the growth of the musical form, a dynamic American byproduct of blues and country, from its first big beat. But so did the fans’ cameras.

Even as professional photographers created a new genre by freezing the action of vibrant concert performances or staging elaborate portraits of rock’s royalty, concertgoers never stopped taking pictures of their favorite performers, whether they used Instamatics or Instagram.

Now Smithsonian Books is inviting anyone who has taken a picture of their favorite artist to send it in to be included in a massive crowd-sourced site of live rock ‘n’ roll performances, to be seen alongside some of the most familiar images of rock stars by photographers so well known, they are often considered rock stars themselves.

Upload Your Photos Now!

Upload Your Photos Now!

Upload Your Photos Now!

The Smithsonian and guest editors will showcase the best of the submitted photos online. And the very finest will end up in a book to be published in the fall of 2017 that will include the photographic works of both fans and professionals.

“There will be somewhat of an editing process,” says Bill Bentley, a longtime music industry figure who will be the author of the forthcoming book. But as for the website, he adds, “It’s going to be very democratic.”

He hopes to include the many rock images that have great meaning to him.

“When I was a kid in the 1950s, I got hooked on Elvis, and I remember seeing a photograph of Elvis in 1956 in Waco,” Bentley says of his years growing up in Texas.

“So I’m trying to track that photographer down or his estate so it can be included.”

“And as I grew up with music all these years,” he adds, “I remember seeing great photographs of the soul singers in the '60s—James Brown and Otis Redding and then in rock, The Beatles, of course, and the Stones, but even more than that the American bands, the psychedelic era, from 1965 on, seeing photos of shows in San Francisco. I was stuck in Texas thinking, oh gosh I wish I was in Haight-Ashbury seeing the Grateful Dead at the Avalon.”

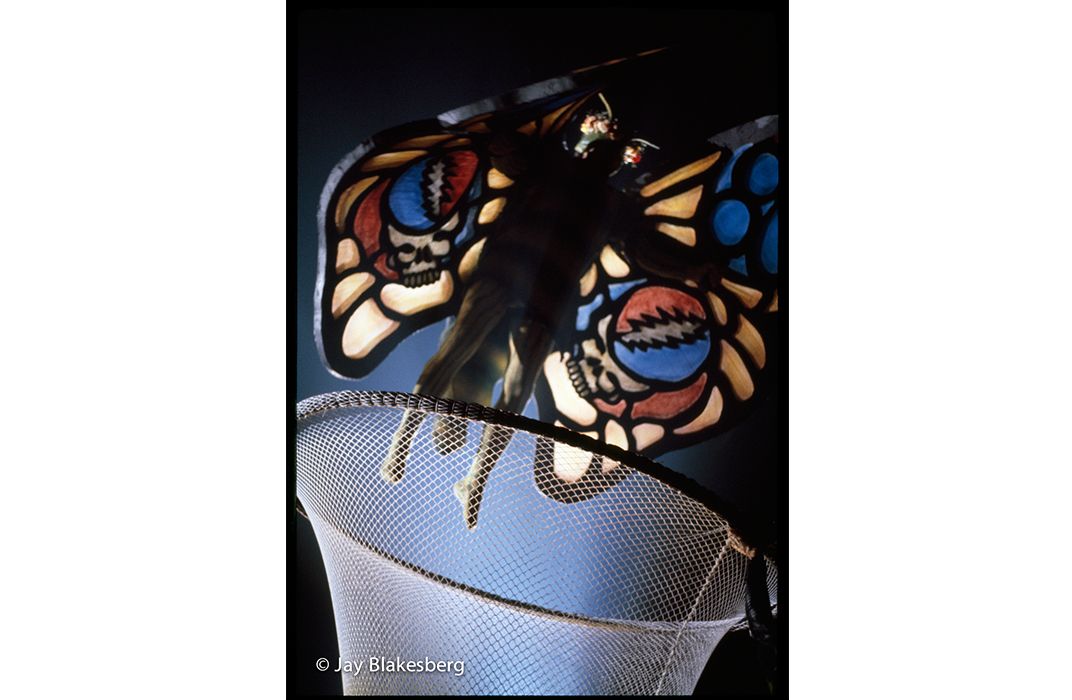

One person who had similar dreams of the Grateful Dead, more than a decade later, was Jay Blakesberg, who as a teenager in New Jersey borrowed his dad’s camera to chronicle his second-ever Dead show at Giants Stadium on Labor Day, 1978. Later that year he was back shooting it as a fan at the Capitol Theatre in Passaic, New Jersey. “What I was doing was trying to get things I could tack onto my bedroom wall,” he says.

But when he caught the Dead at a anti-nuclear concert in Washington, D.C., the following year, he sent his photo to Relix, a rock magazine eager to show readers the group’s newest member, keyboardist Brent Mydland. “It was one of the first photos of Brent,” Blakesberg says, adding with a laugh. “There was no speed-of-light transfer then and fans had to wait to see it in a monthly magazine two months later.”

Still, it was hard to break into big rock magazines, until he got a call from Rolling Stone, whom he had been pestering, to capture U2’s 1981 rooftop concert in San Francisco, where he had relocated.

“Since then, I’ve had 300 assignments from Rolling Stone,” he says. “I quit my job for a video production company and started making my living as a photographer.”

Working for the regional BAM music magazine, he shot the first covers in the career of Counting Crows and Alanis Morissette.

Getting all access passes on stage meant he got the kind of shots kids in the seats couldn’t dream of getting, culminating with the Dead’s huge 50th anniversary “Fare Thee Well” shows last July in Chicago. One particular pre-show shot of the remaining band on stage, with the crowd of 70,000 cheering behind them, was not only one of the year’s most iconic rock photographs, but one of the most memorable in the band’s proverbial long, strange trip.

It’s also the cover of Blakesberg’s latest coffee table book of rock photography—his 11th—Fare Thee Well, which has just been released. “What’s interesting is that the major landmark of my career came 38 years since I was the stupid stoner kid from New Jersey, standing on a step stool to get a good shot.”

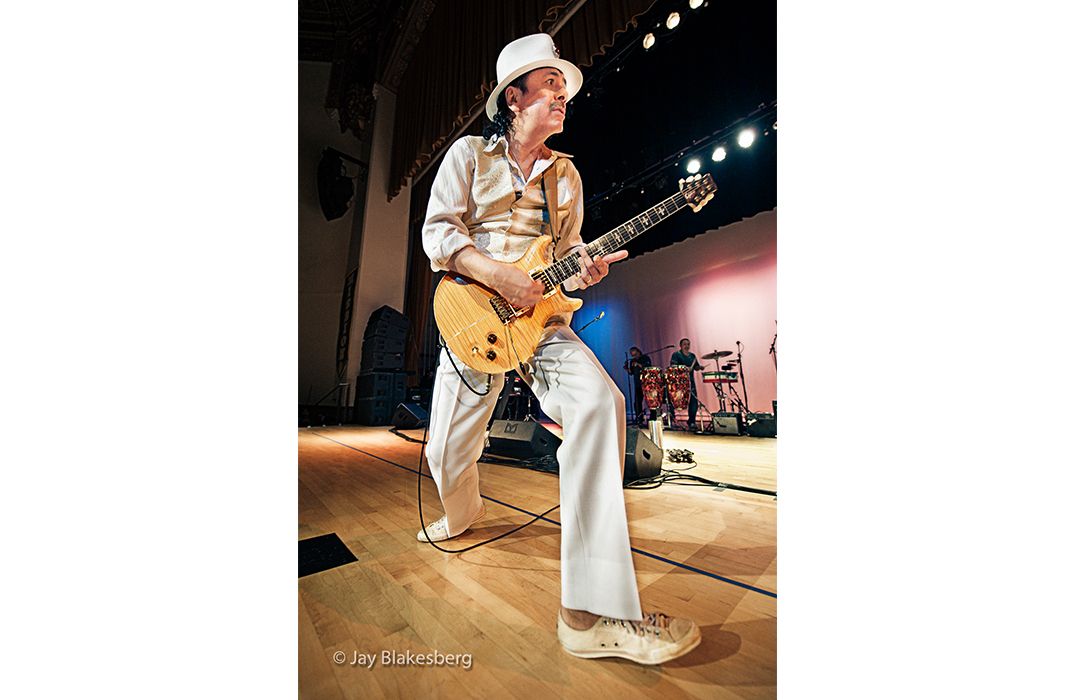

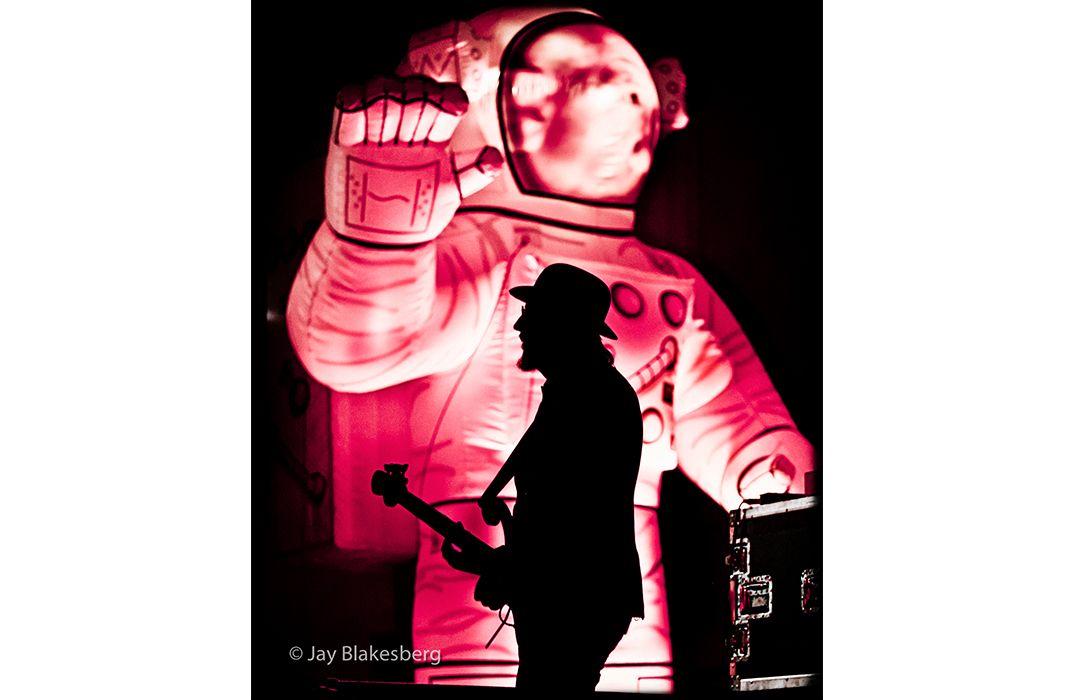

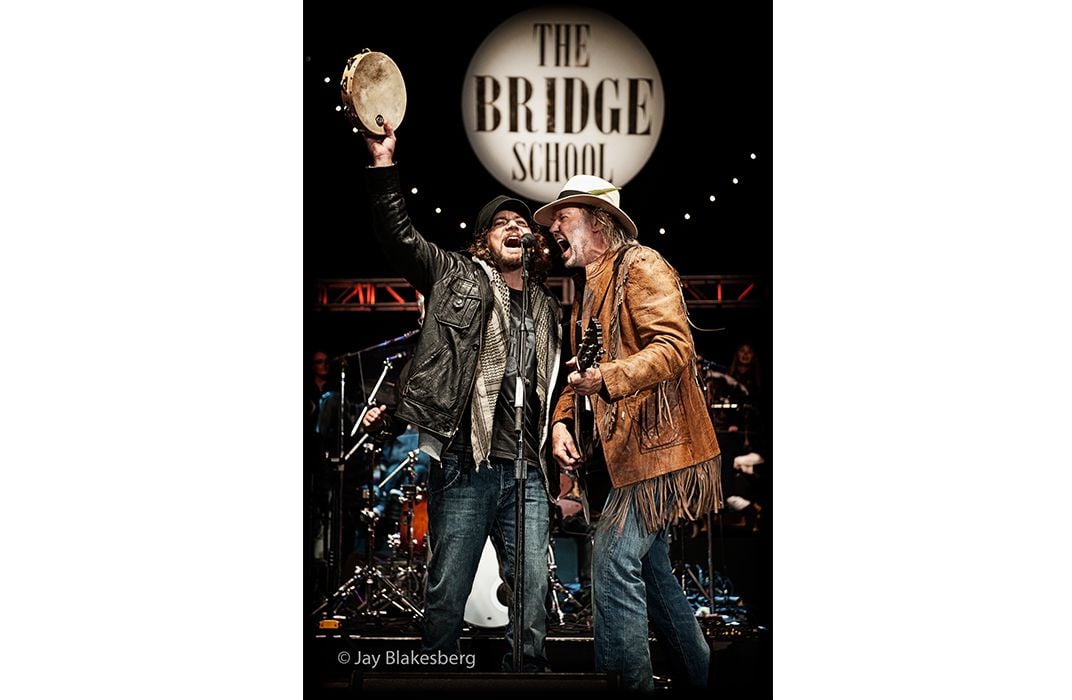

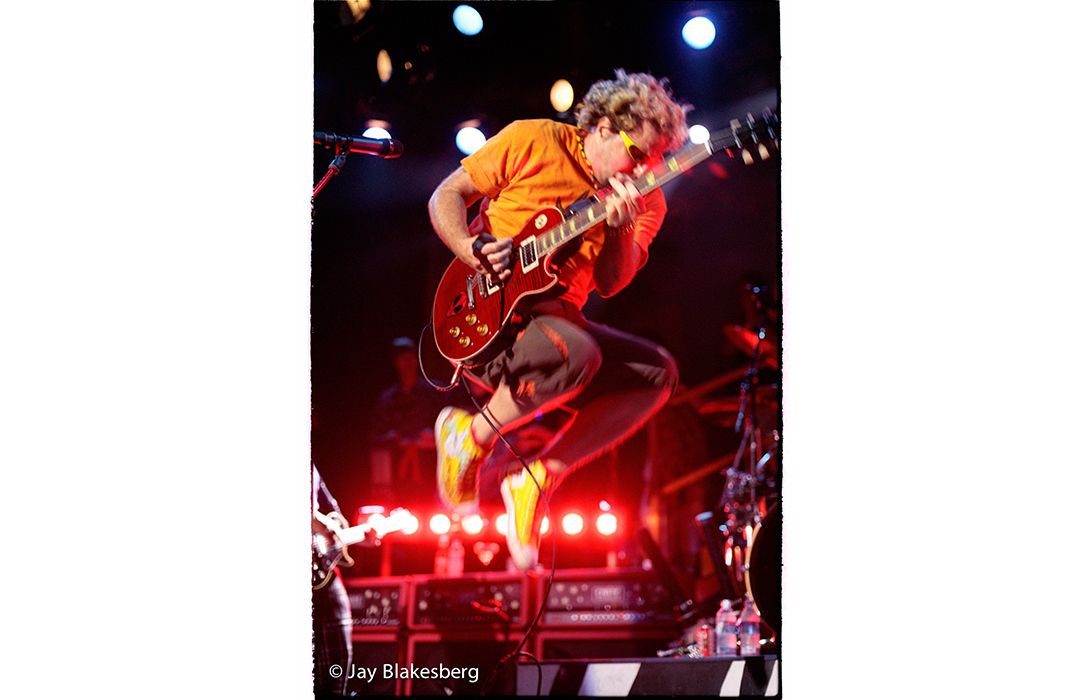

The shot is also part of work that can be seen at the Smithsonian Books' Rock ‘n’ Roll site, amid his pictures of Carlos Santana, Neil Young with Eddie Vedder, Primus and Michael Franti.

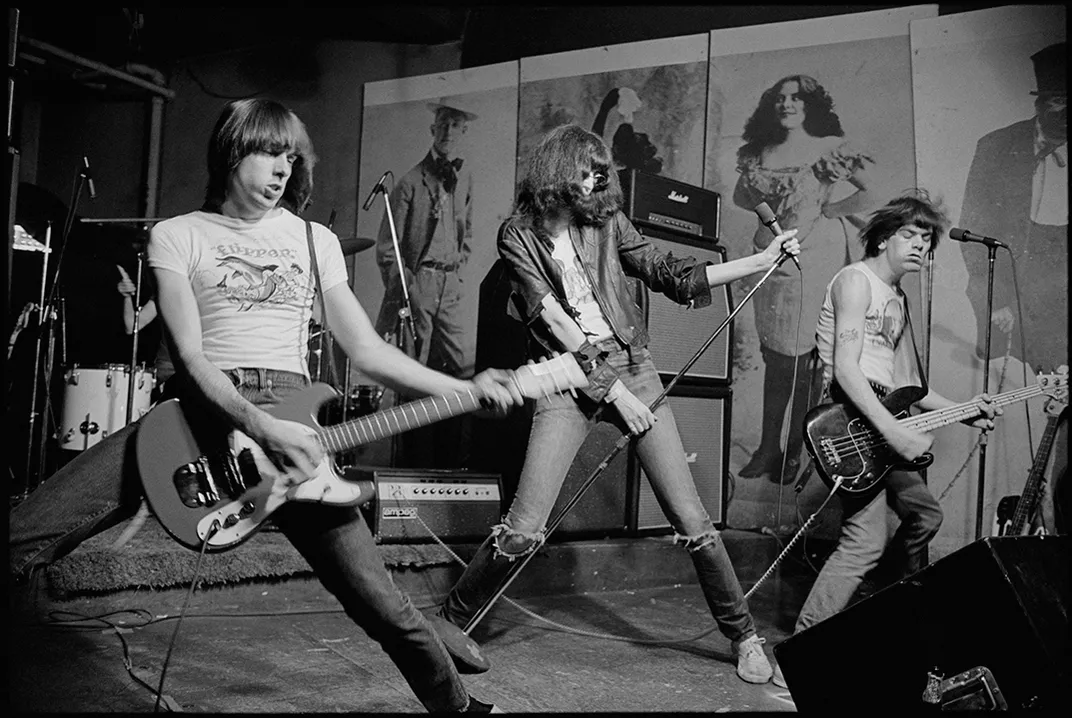

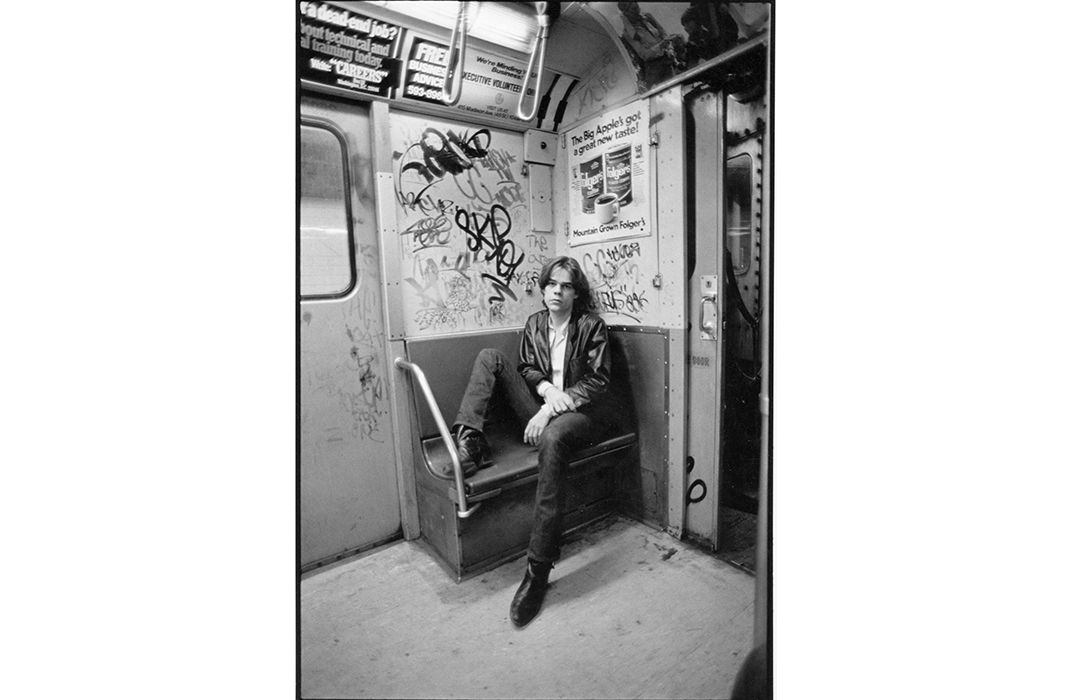

If Blakesberg became one of the leading chroniclers of the Dead and the jam bands the group inspired, it was Roberta Bayley who captured the look of the burgeoning New York rock scene of the mid-1970s.

Bayley had been a shutterbug and a rock fan since seeing the Beatles and Rolling Stones on tour when she was growing up in San Francisco. “I did take Instamatics of the Rolling Stones, which I still have,” she says over the phone from New York.

But it wasn’t until a decade later, living in New York City that she began capturing the scene flourishing all around her.

“I fell in with the music scene there,” she says. “This interesting group of people seemed fascinating to me and I became part of it.”

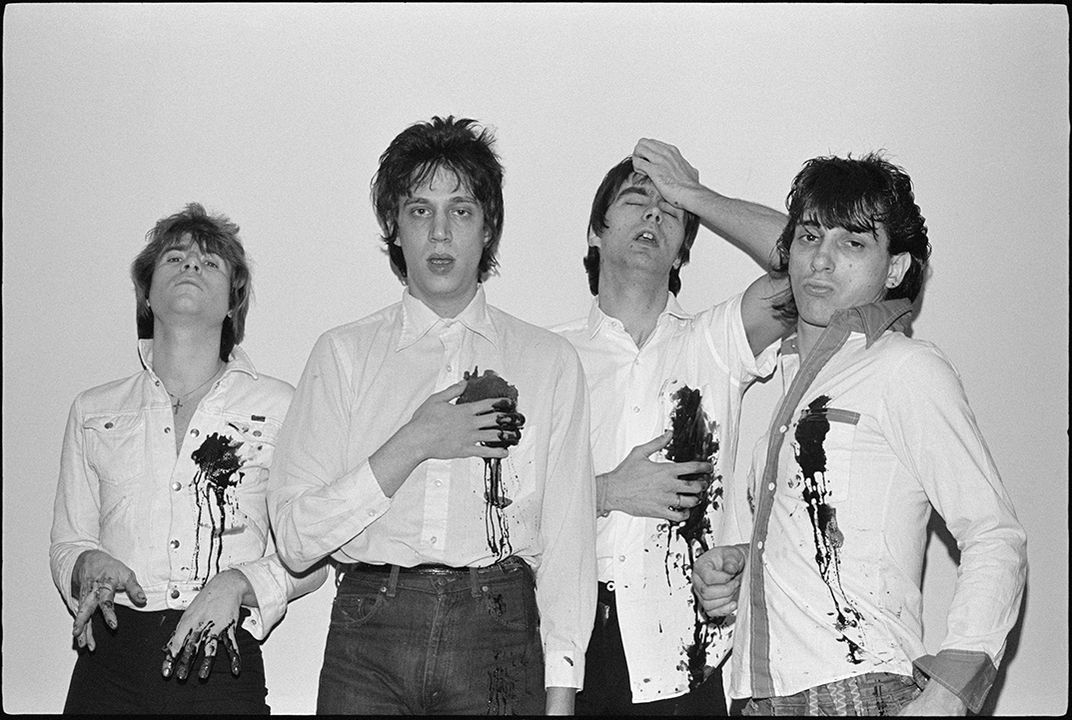

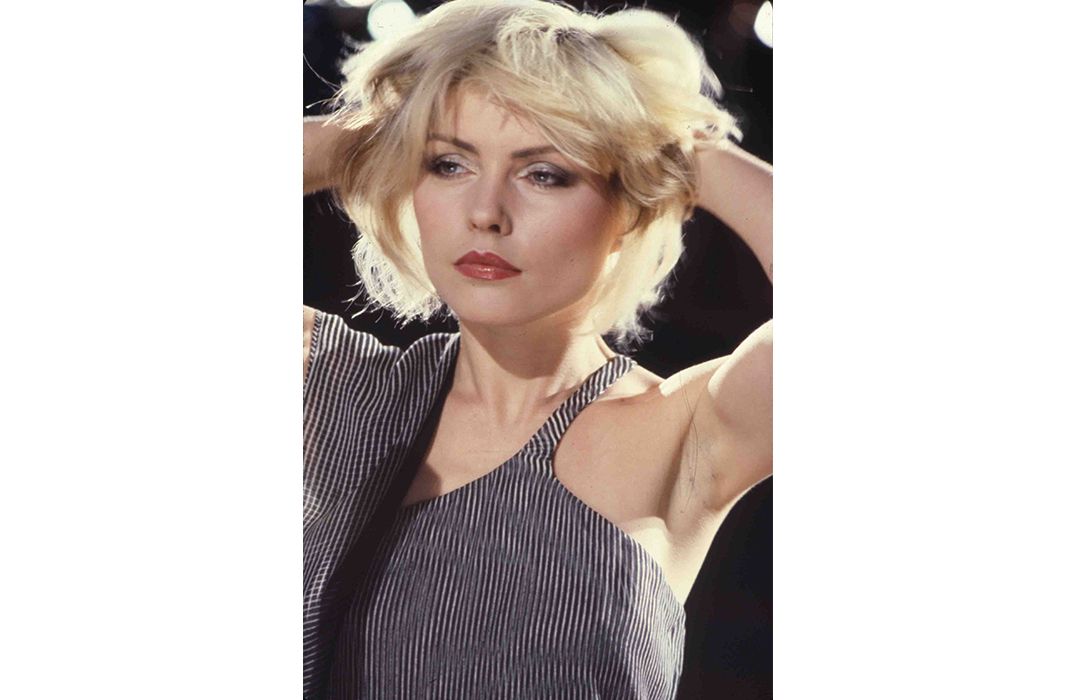

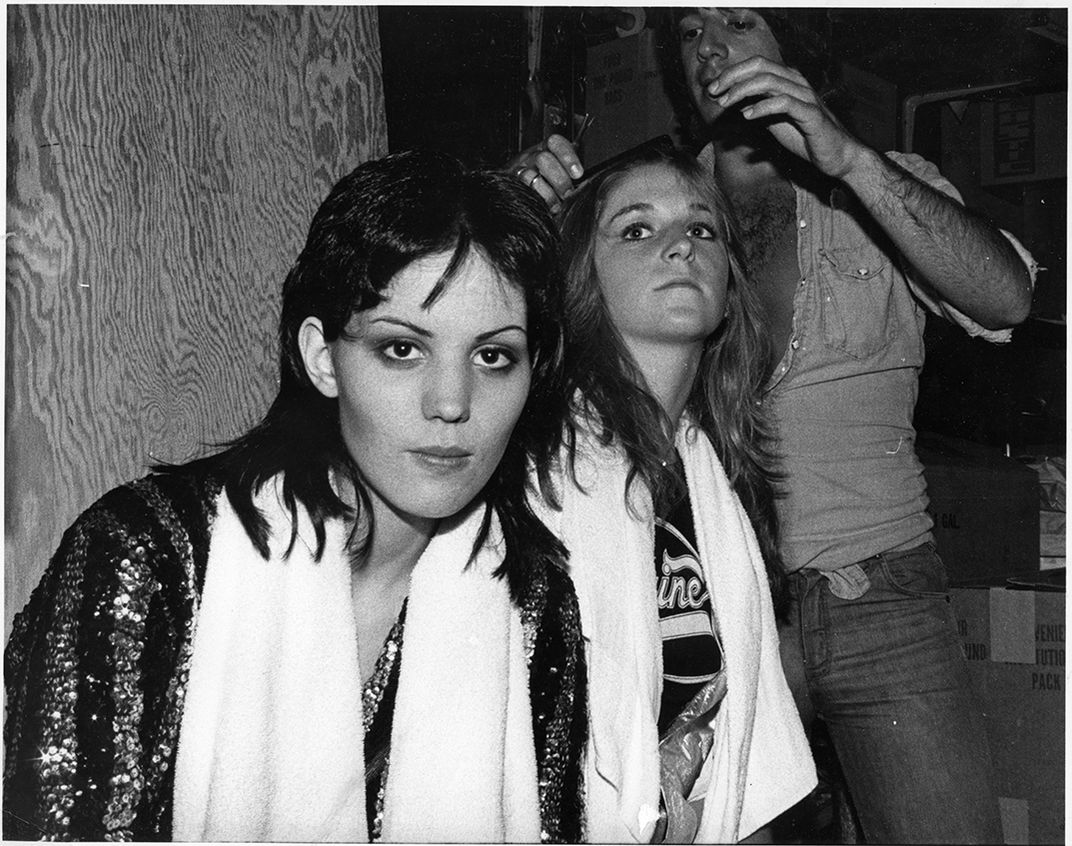

She was Richard Hell’s girlfriend for awhile, worked the door at the legendary CBGB’s club and befriended the guys who created Punk magazine. There, shooting the likes of Blondie, Television and the New York Dolls, she established a gritty, visual aesthetic to go with the music.

But that wasn’t her intent, she says. “Everything wasn’t dictated by the aesthetic of the time; it was dictated by the dollars in your pocket.” Color film was expensive, she says. “That’s why people worked more in black and white.”

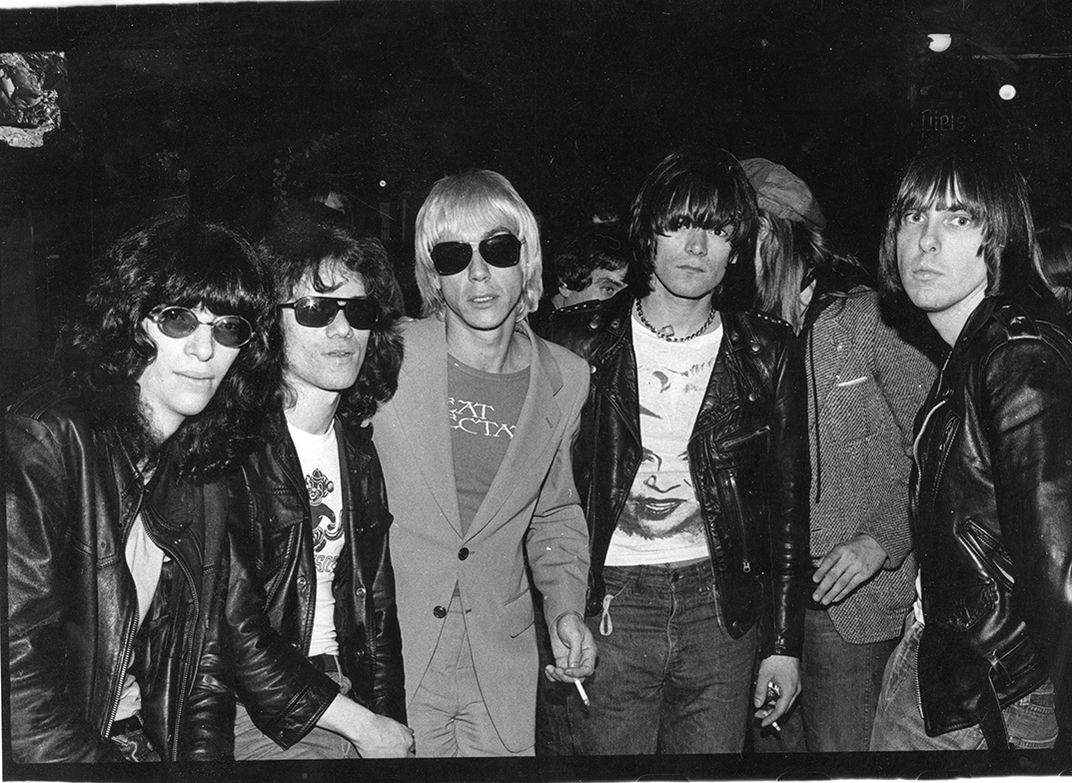

A shot she took for the third issue of Punk magazine of The Ramones, with the band standing in their leather jackets and ripped jeans next to a brick wall in the Bowery, became the striking cover for the band’s 1976 debut album.

“I couldn’t be happier the band was in black and white,” Bayley says. “They were the perfect band to be in black and white.”

Despite being named one of the great album covers of all time, it didn’t make her rich. “I got paid $125 for the Ramones cover,” she says. But since she didn’t sell a lot of her work, she retained rights to it, which was helpful when she decided, a decade after “phasing myself out” of rock photography, she began to mount exhibitions about the early days of punk.

“The brilliance of my career in retrospect is that nobody ever paid me,” Bayley says. “Therefore I owned my copyrights.”

These days, credentialed photographers at rock concerts are sometimes asked to sign waivers that give the rights of the photographs to the act. That’s in addition to other restrictions that include shooting the first three songs only with no flash, and often fighting the crowd to get position.

“Photographers seemed to have the hardest job,” Bentley says. “They’d have these thousand dollar cameras and have to battle the fans to get close to the stage before there was such a thing as photo pits. It was an expensive and brutal profession, only to be paid very little money and often get little recognition.”

“I once likened it to a combat photographer,” says Bayley, who once had a sleeve ripped from her cashmere sweater by a bouncer at a Clash show. “But it’s even worse than that—pushing people out of you way, dealing with the audience, being in the fray.”

What keeps photographers doing it?

“I think it’s the excitement of music,” Bentley says. “You wanted to go to the shows and get close to it. And of course your job was getting the great shot, to share that excitement with whoever is going to see it. I think it was an age group thing of the love of music to really get next to it.”

“I still have excitement for Grateful Dead music,” says Blakesberg. Though the downturn in the music business and switch to digital processes was difficult, “I got back to liking what I was shooting, very much enjoying being in the pit, being on the stage, being in the jam band world and hopefully producing inspiring and great photographs.”

At a time when everybody in the audience has a camera through their phones, it still takes a special eye to be a professional, Bentley says.

As Bayley puts it, “I had seen a lot of music and had an idea of when to push the button.”

What advice do the professionals have for the fans shooting from the seats?

“It depends what they want it for,” Bayley says. “When I went to see the Beatles in 1964, playing a 17,000 seat concert hall, when they walked out it was like white light, 1,600 kids shooting flash. The whole place was amazing. They’d shoot and shoot and shoot. I think it’s weird you wouldn’t want to watch the concert. But everyone is more into second hand experience. They go home and look at it later.“

“Lighting is always key,” says Blakesberg. “People don’t realize they’re taking photos in a very dark situation. That’s why things get very pixilated, the exposure is out and some people like to zoom, so you get these big golf ball-sized pixels.”

All fan-derived pictures are welcome to be sent to the crowd-sourced Smithsonian Books site, though only a select few will make it into the eventual book.

“This seems to me like a very egalitarian way for great music photographs to be seen,” Bentley says.

RockandRoll.si.edu features photos and text from rock artists, band managers, photographers and more sharing their favorite images and stories. The site offers easy-to-use upload options for fans to post archival and current rock concert photographs. The accompanying book will be published in the fall of 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/e7/4ce7ac55-b953-4fa2-bb1c-96f6f5fa30e7/ramonescover76web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)