Lost in Space and Other Tales of Exploration and Navigation

A new exhibit at the Air and Space Museum reveals how we use time and space to get around every day, from maritime exploration to Google maps

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Air_Thumb.jpg)

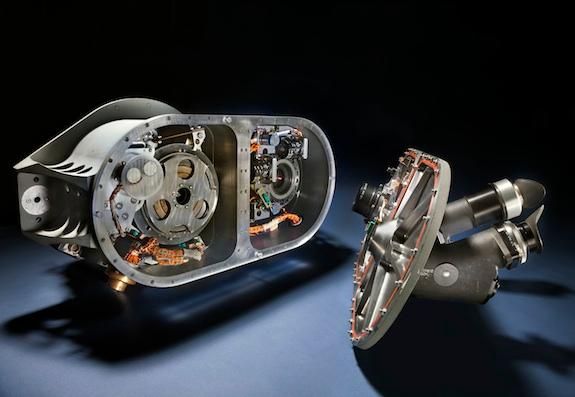

The first several Soviet and American spacecrafts sent to the moon missed it completely, crashed on the moon or were lost in space, according to a new exhibition at the Air and Space Museum. Navigation is a tricky business and has long been so, even before we ever set our sights on the moon. But the steady march of technological advances and a spirit of exploration have helped guide us into new realms. And today, any one with GPS can be a navigator.

From the sea and sky to outer space and back, the history of how we get where we’re going is on view at the National Air and Space Museum’s new exhibit “Time and Navigation: The Untold Story of Getting from Here to There,” co-sponsored by both Air and Space and the National Museum of American History.

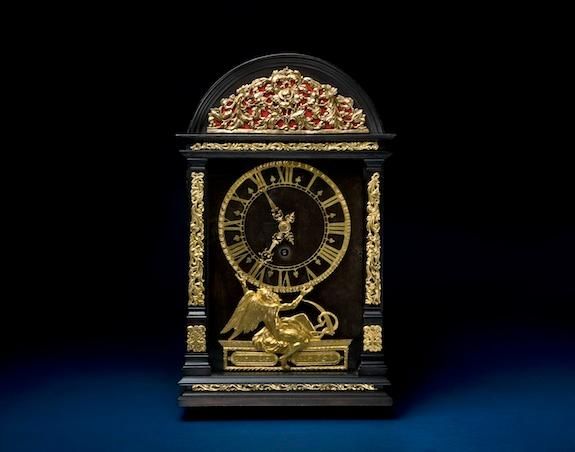

Historian Carlene Stephens, who studies the history of time and is one of four Smithsonian curators who worked on the show, says: “If you want to know where you are, if you want to know where you’re going, you need a reliable clock and that’s been true since the 18th century.”

That interplay of time and space is at the heart of the exhibit—from sea to satellites. As technology allows for greater accuracy, so too does it ease navigation for the average user, so that by World War II, navigators could be trained in a matter of hours or days.

What began as “dead reckoning,” or positioning oneself using time, speed and direction, has transformed into an ever-more accurate process with atomic clocks capable of keeping time within three-billionths of a second. Where it once took roughly 14 minutes to calculate one’s position at sea, it now takes fractions of a second. And though it still takes 14 minutes to communicate via satellite with instruments on Mars, like Curiosity, curator Paul Ceruzzi says, we were still able to complete the landing with calculations made from earth.

“That gives you a sense of how good we’re getting at these things,” says Ceruzzi.

The exhibit tells the story with an array of elegantly crafted and historical instruments, including models of clocks designed by Galileo, Charles Lindbergh’s sextant used to learn celestial navigation, artifacts from the Wilkes Expedition and Stanley, the most famous early robotic vehicle that can navigate itself. It as much a testament to the distances we’ve traversed as it is to the capacity of human intellect that first dreamed it was all possible.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)