The Magnificent Musical Life of the Upside-Down Guitar Player Libba Cotten

Musician and author Laura Veirs brings this musical icon back to the stage in her recent children’s book

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/fa/fcfa022d-262a-49b3-83f9-de5a80fd8087/page3libba.jpg)

Singer-songwriter Laura Veirs wants kids to know that they can turn things upside down and do things their own way—just like left-handed, GRAMMY Award-winning folk singer Libba Cotten, who played her right-handed guitar upside down.

In her recent children’s book Libba: The Magnificent Musical Life of Elizabeth Cotten, illustrated by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, Veirs shares the story of the influential African American singer and guitarist who learned to play at a young age but did not attempt commercial success until her sixties.

Cotten grew up poor in a segregated North Carolina of the early 1900s and began by playing her brother’s banjo. She played it wrong-side-up without restringing it, then did the same with the family guitar. Life circumstances—marriage, birth and divorce—kept Cotten from playing music for nearly 40 years.

Then, when Cotten was nearing 60 years old, she was working at a department store in Washington, D.C., when she returned a lost child to her mother. The mother turned out to be Ruth Crawford Seeger, an influential folk musician and composer, who was the mother of Mike Seeger, and the stepmother of Pete Seeger. The lost child was Peggy Seeger, who also would grow up to become a performer. Cotten began working in their household as a cook and maid. In a home full of musicians, her love for music was rekindled. With the help of the Seeger family, she recorded an album, toured around the world, and eventually at the age of 90, won a GRAMMY.

A folksinger herself, Veirs has been playing Cotten’s music for many years. “When I became a student of country blues guitar in Seattle in the 1990s, I learned quite a few of her songs in detail,” she says. “They’re very difficult to play. Even though the basic melody is simple, the accompanying parts on the guitar are very complicated.”

Libba: The Magnificent Musical Life of Elizabeth Cotten (Early Elementary Story Books, Children's Music Books, Biography Books for Kids)

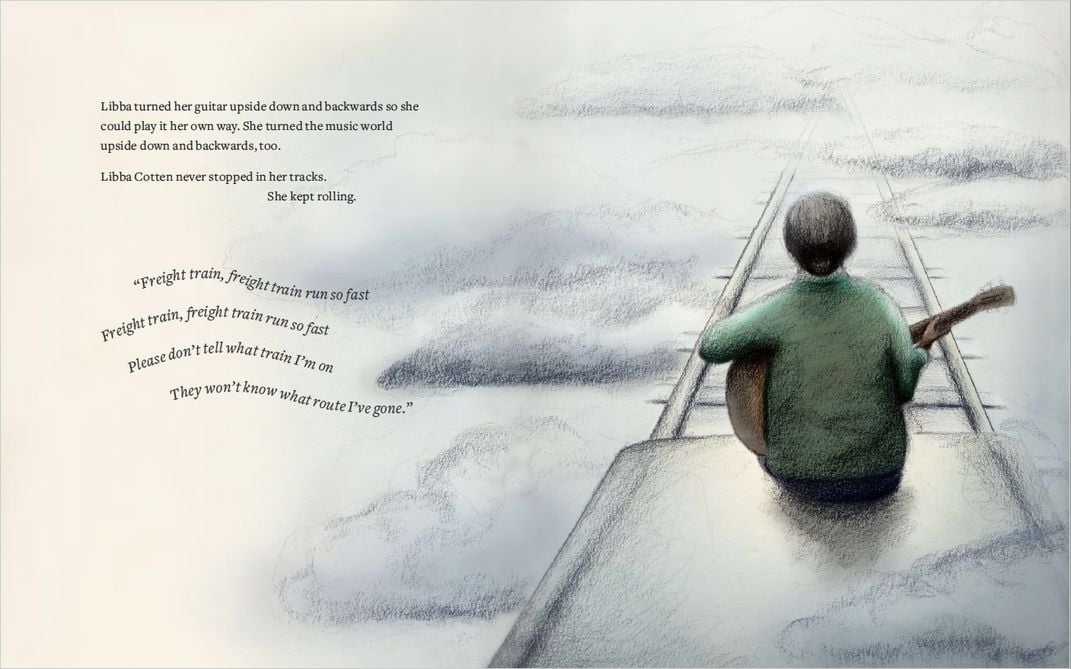

Elizabeth Cotten was only a little girl when she picked up a guitar for the first time. It wasn't hers (it was her big brother's), and it wasn't strung right for her (she was left-handed). By age 11, she'd written "Freight Train," one of the most famous folk songs of the 20th century.

Veirs finds inspiration in Cotten’s story: the message of never giving up, that most people are capable of doing amazing things, and, most importantly, that “just because something is laying in hiding doesn’t mean it isn’t still there.”

The singer is intrigued by the story of an artist who achieved success so late in life and who taught herself to play in such a unique way. Veirs notes the barriers that Cotten faced in becoming a musician. She was young, poor and black and it wasn’t practical to become a musician. Even the church discouraged her from playing music.

As a mother, Veirs was drawn to the picture books she was sharing with her children. “I think it’s a really beautiful art form, and I love reading to kids.”

Writing Libba was, for Veirs, both natural and challenging. One of the most rewarding parts of her research was talking with Cotten’s great-granddaughter, Brenda Evans, who shared stories that enriched Viers’ understanding of Cotten’s personality, mannerisms and idiosyncrasies. Raised by Cotten, Evans, who is also a musician, sang and co-wrote with Cotten the folk classic “Shake Sugaree” at age 12. Veirs and Evans even played “Shake Sugaree” together live when Veirs visited D.C.

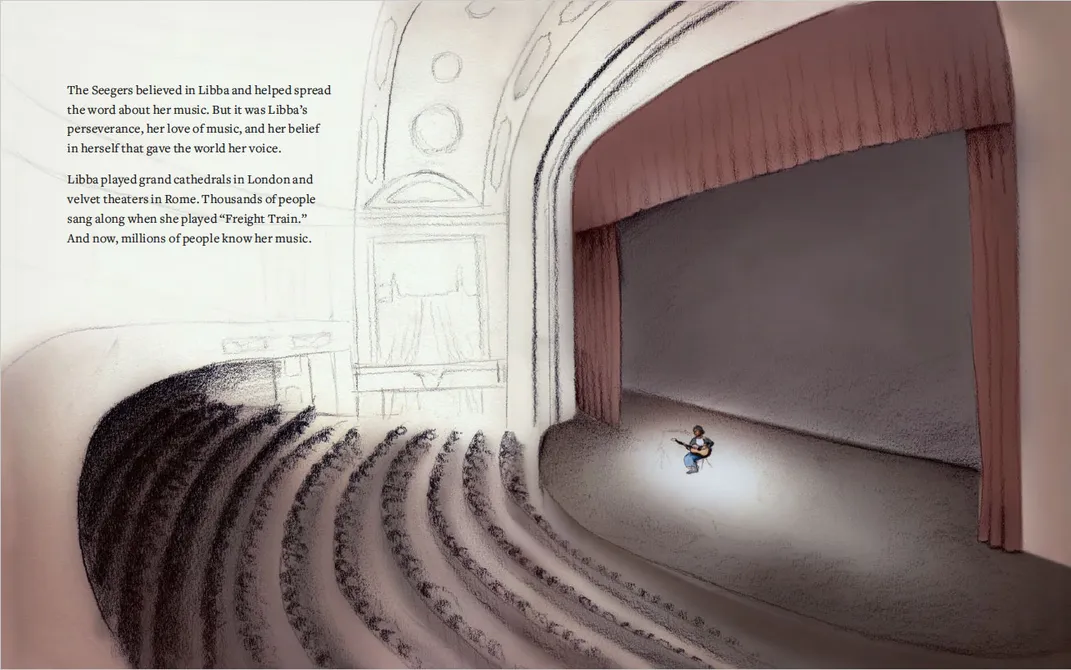

But Veirs had concerns. How could she, a white woman, deliver the proper agency to her subject in telling the black woman’s story. She sought out the help of an expert at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco. “Those small things are actually big things when it comes to writing a picture book, because you only have so many words,” Veirs says. “It’s similar to a song in that way. You just don’t have a lot of time or space to say the things you want to say. So every word needs to count.” To Veirs it was critical that Cotten’s success not be depicted as a product of the Seegers’ help, when in fact, it was Cotten, who was “driving the ship.”

“The Seegers believed in Libba and helped spread the word about her music. But it was Libba’s perseverance, her love of music and her belief in herself that gave the world her voice,” says Veirs.

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, an artist better known for her street art and murals, illustrated Libba with her beautifully muted, full-page illustrations. Dusty gray backgrounds and heavy shadows convey the struggles that pervaded Cotten’s life. But Cotten’s enduring optimism and lifelong passion for music is conveyed in the bright colors of her warm smiles—Veirs’ favorite parts of the illustrations.

Cotten’s manager John Ullman, who wrote the liner notes for her posthumously produced 2004 album Shake Sugaree, produced by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, reflects on the beginnings of Cotten’s musical career, when she traveled to folk festivals, coffee shops, colleges, and elementary schools around the country. She fascinated both the young and old, all equally amazed by an 80-year-old recording artist who sang with such heart.

Cotten died in 1987. Ullman muses, “The true measure of her legacy is the tens of thousands of guitarists who have included her songs as a part of their repertoires.”

Veirs is certainly a member of this cohort. She cared about Cotten’s story and wanted others to care too. By reaching out to children, she is creating a new audience for Cotten’s fascinating history and inspiring perseverance.

As the book concludes: “Libba Cotten never stopped in her tracks. She kept rolling.”

A version of this story appeared in the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

Riley Board is an intern at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a sophomore at Middlebury College in Vermont where she studies linguistics and geography.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.