Marcel Duchamp Played With the Definition of Art and Now the Public Can, Too

Art connoisseurs Aaron and Barbara Levine amassed a formidable body of the artist’s works; they’d like nothing better than for you to see it

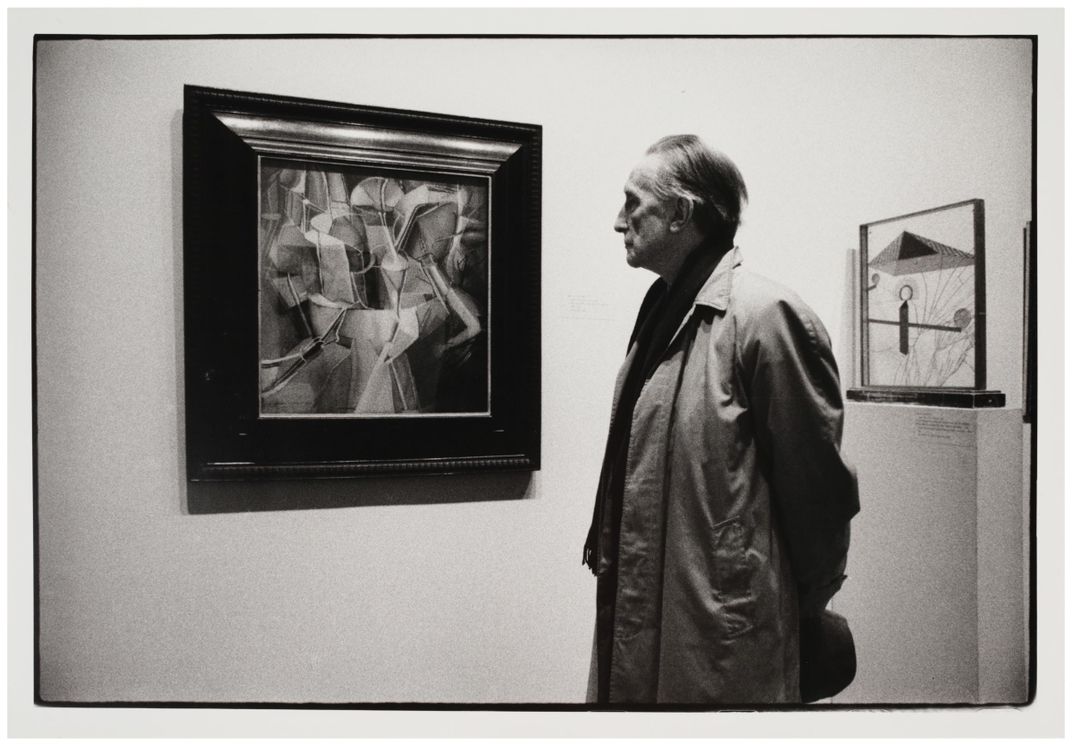

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/78/a878a571-ea82-47ca-9e1c-11ef13602745/031_duchamphenricartierbres_cropped.jpg)

For art enthusiasts Aaron and Barbara Levine, obtaining an edition of Marcel Duchamp’s The Box in a Valise 20 years ago served as a kind of Pandora’s Box into that artist’s world.

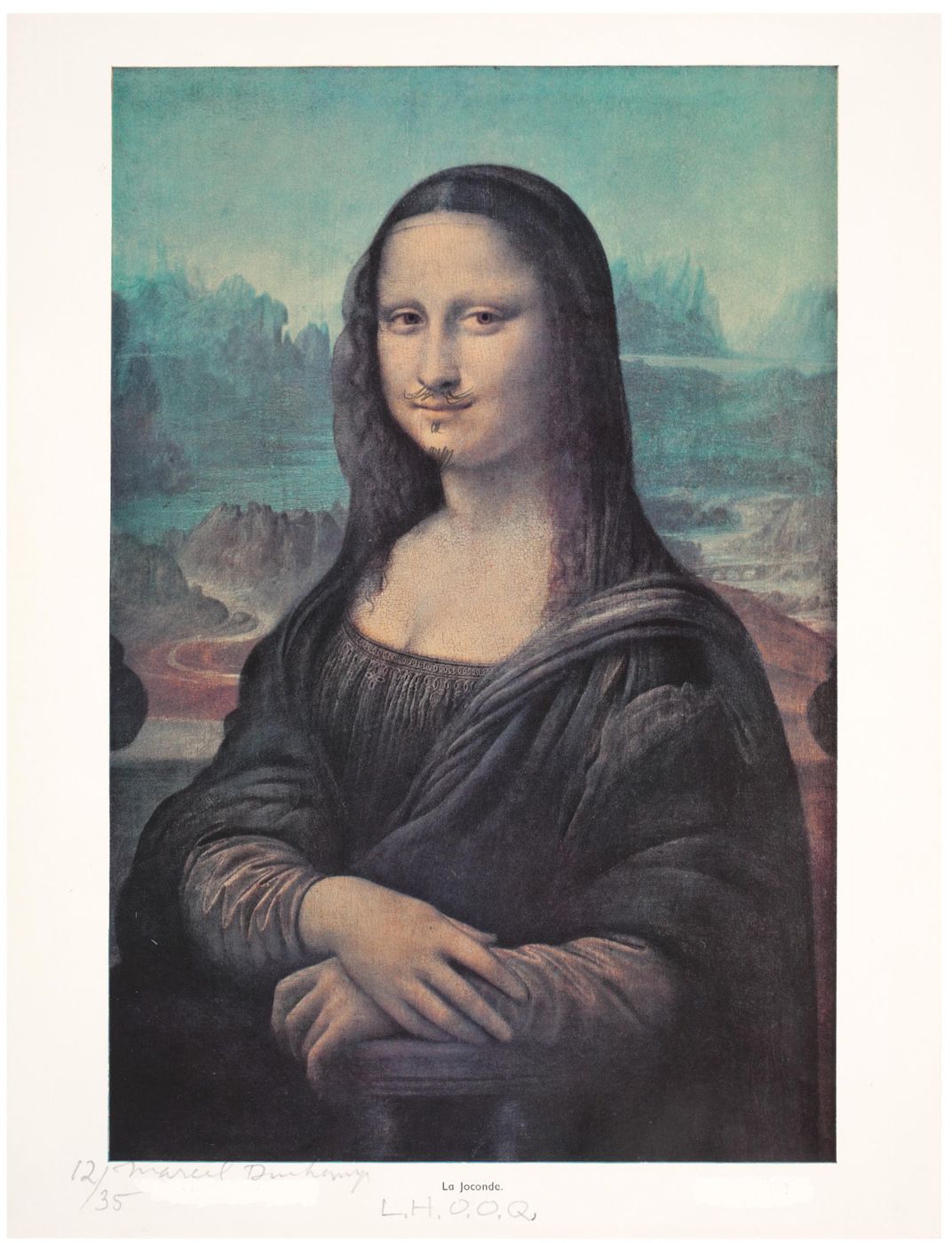

Inside the meticulous work, with its sliding compartments and unfolding displays, were miniature representations of 68 Duchamp works over half a century. Among them are those that shook and continued to influence the art world, from Nude Descending a Staircase and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even to his readymades and the mustache he put on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa.

Duchamp worked on the kind of greatest hits’ collection from 1935 to 1968 and described it in 1955 as a “box in which all my works would be mounted like in a small museum, a portable museum, so to speak, and here it is in this valise.”

It also became a kind of roadmap for the Levines in finding further works by the artist who died 51 years ago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/4d/534d6112-17ce-494e-a33e-3ced5e133d5b/hmsg_levineportrait_cc.jpg)

“He absolutely went crazy about it,” Barbara Levine says of her husband’s reaction to the artist behind The Box in a Valise. “It became such a major aspect of our lives. and I became totally absorbed in it also.”

And in the intervening two decades, the couple amassed one of the most formidable private collections of Duchamp’s work, representing all parts of his career, which they have now turned into a promised gift to the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

“This is a real milestone in our museum’s history,” says museum director Melissa Chiu. “This is in fact the most important donation by individual collectors since our founding gift from Mr. Hirshhorn which founded our museum in 1974.”

And now the public can see the riches of their collection with the opening of the exhibition, “Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection.”

“We’re super excited about this show,” Chiu says. “This is nearly 50 works by one of the leading artists of the 20th century who has only grown in statue and importance.”

And inside the show is that inspirational box, whose full title From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rose Sélavy (The Box in a Valise), mentioning the pseudonym he often used, as on a 1921 sculpture in the show, presented in a 1964 edition, Why Not Sneeze?

If the box works as “a mini-museum,” as curator Evelyn Hankins puts it, it’s reflected in the show. “The extraordinary thing about this is that the gift encompasses the entire arc of Duchamp’s career,” Hankins says, “From an early drawing in the first gallery of his sister in Bonn from 1908 that he made as a student, to works from the 1960s right before his death.”

From that early drawing, Duchamp changed styles quickly, beginning with his furiously cubist Nude Descending a Staircase that caused a sensation at the famous 1913 New York Armory Show of modern art—and former President Theodore Roosevelt called “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection

This strikingly designed volume, with fold-outs and comparative illustrations, places Duchamp squarely in the context of both modern and contemporary art, and affirms his radical status as an artist with continued relevance today.

A 1936 collotype is included of that work at the Hirshhorn. And while the original The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) cannot travel from the Philadelphia Museum of Art due to its fragility, there are “an exceptional array” of objects that relate to it, Hankins says, from early prints and sketches—to 93 miniatures of them, some of them painstakingly reproduced for another work known as The Green Box.

“Duchamp kept all these working notes when he was thinking about it. He worked on this piece when he was in Paris, when he was in Munich, when he was in New York. It was a project he thought about and worked on for many years,” she says.

Years later, he began meticulously reproducing the notes for the work and assembling them for the box, she says, “What this work makes manifest is the idea that artists’ ideas are art works in themselves. But he also challenges ideas about authenticity and originality—where is the art work? Is the art work in the mind? Is the art work in Philadelphia?”

For conservation reasons, the papers that are shown with the box will be rotated as the exhibition continues, as will the items in The Box in a Valise. And sifting through the notes, in whatever order, makes the viewer part of the presentation.

”That’s really a critical part of Duchamp’s contribution to art,” Hankins says, “this idea that the viewer is just as important in the creation of meaning as the artist himself. You can imagine what a radical idea this was in the 1920s when he proposed that.”

“It’s all about pushing art into the mind,” Aaron Levine says. “The only way you’re going to get this stuff is to think about it and absorb it and by getting into the mind of the artist.” What might otherwise look like a hat rack, or a ball of twine, or a birdcage full of marbled cubes becomes, through its isolation and presentation by an artist, art, Levine says. “It’s in your head where the art will come alive.”

And while Duchamp’s work led to the foundation of conceptual art, there were also some lovely work he made, not least of which are the curls of the hat rack that flies in the air, alongside its equally elegant shadow. Still, he thumbed his nose at how rarefied fine art had become, famously drawing a mustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa.

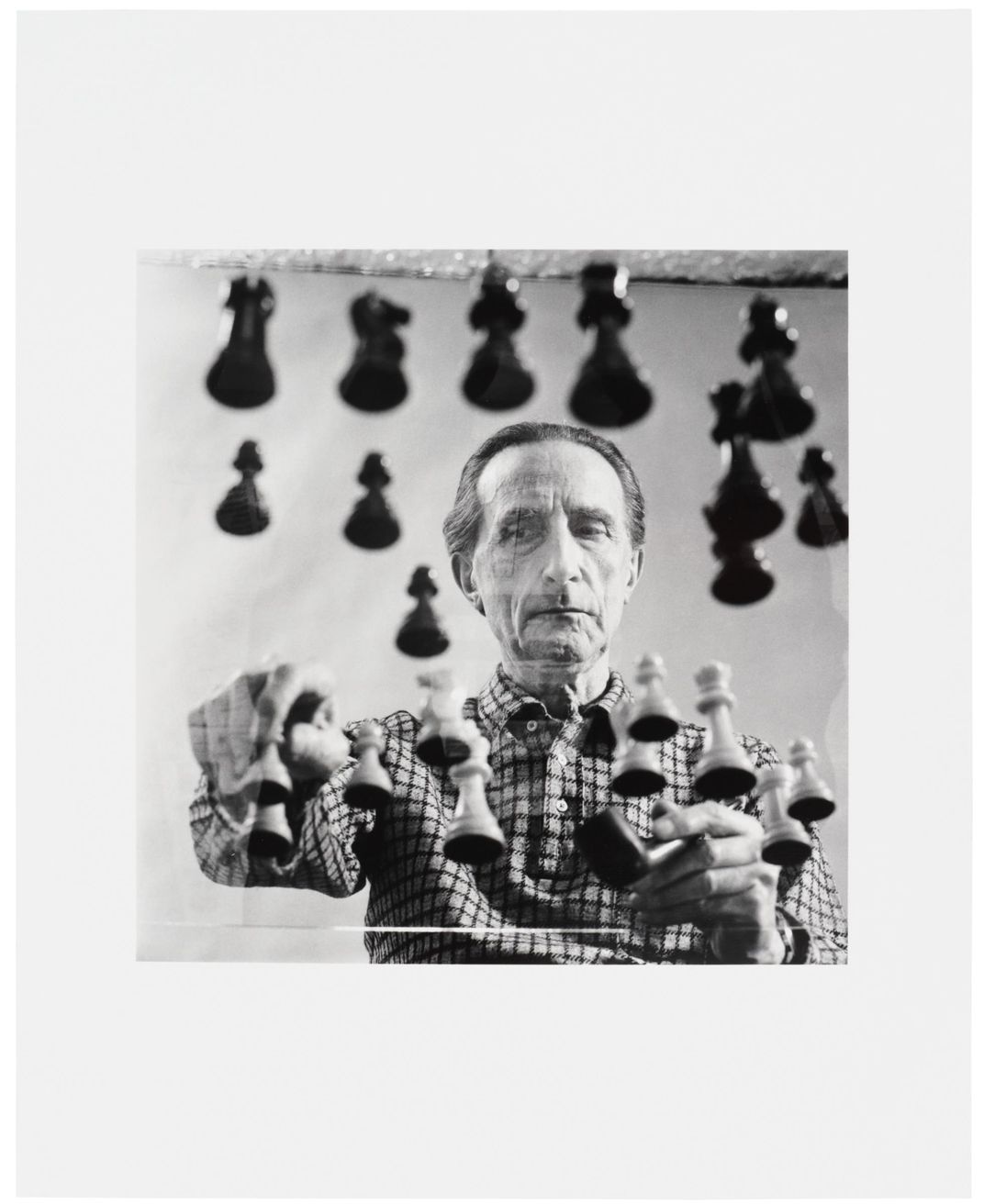

But he worked in other fields as well, creating spinning kinetic works that are on display in one room. The exhibition ends with a number of interactive opportunities of practices Duchamp enjoyed, from chess to silhouettes. A second stage of the exhibition, opening April 18, 2020, will look at the lasting impact of Duchamp on modern and contemporary artists through the holdings in the Hirshhorn’s permanent collection. That show is also curated by Hankins, who oversaw an accompanying 224-page publication.

Barbara Levine said they chose the Hirshhorn to receive their gift not only because they live in Washington, D.C., where she was a member of the board, but mostly because, as with the other Smithsonian museums, admission is free. “Hopefully there will be a lot of young people who come through here and experience Duchamp where they never would have had the chance before,” she says.

Aaron Levine says if seeing what Duchamp created triggers the imagination of a fraction of the young people who may visit after a trip to the Air and Space Museum next door, “even 10 percent,” he says, “I’ll be more than happy.”

"Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection" continues through October 15, 2020 at the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)