Margaret Hamilton Led the NASA Software Team That Landed Astronauts on the Moon

Apollo’s successful computing software was optimized to deal with unknown problems and to interrupt one task to take on a more important one

:focal(939x447:940x448)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/1f/c61f96b5-8da2-4715-a792-e3e6bda15714/margaret_hamilton_-_restoration.jpg)

On July 20, 1969, as the lunar module, Eagle, was approaching the moon’s surface, its computers began flashing warning messages. For a moment Mission Control faced a “go / no-go” decision, but with high confidence in the software developed by computer scientist Margaret Hamilton and her team, they told the astronauts to proceed. The software, which allowed the computer to recognize error messages and ignore low-priority tasks, continued to guide astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin over the crater-pocked, dusty crust of the moon to their landing.

“It quickly became clear,” she later said, “that [the] software was not only informing everyone that there was a hardware-related problem, but that the software was compensating for it.” An investigation would eventually show that the astronauts’ checklist was at fault, telling them to set the rendezvous radar hardware switch incorrectly. “Fortunately, the people at Mission Control trusted our software,” Hamilton said. And with only enough fuel for 30 more seconds of flight, Neil Armstrong reported, “The Eagle has landed.”

The achievement was a monumental task at a time when computer technology was in its infancy: The astronauts had access to only 72 kilobytes of computer memory (a 64-gigabyte cell phone today carries almost a million times more storage space). Programmers had to use paper punch cards to feed information into room-sized computers with no screen interface.

As the landing occurred, Hamilton, then 32, was hooked up to Mission Control from MIT. “I was not concentrating on the mission, per se,” Hamilton confessed. “I was concentrating on the software.” After everything worked properly, the weight of the moment hit her. “My God. Look what happened. We did it. It worked. It was exciting.”

Hamilton, who popularized the term “software engineering,” took some chiding for it. Critics said it inflated her work’s importance, but today, when software engineers represent a fervently sought-after segment of the work force, no one is laughing at Margaret Hamilton.

When the Apollo missions were planned, the process of writing code began on large sheets of paper. A keypunch operator would create holes in paper cards, keying the codes into what were called punch cards. “Not too many people know what punch cards are anymore, but that’s how you programmed it,” says Paul Ceruzzi, a curator emeritus at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, who has known Hamilton for the past two decades.

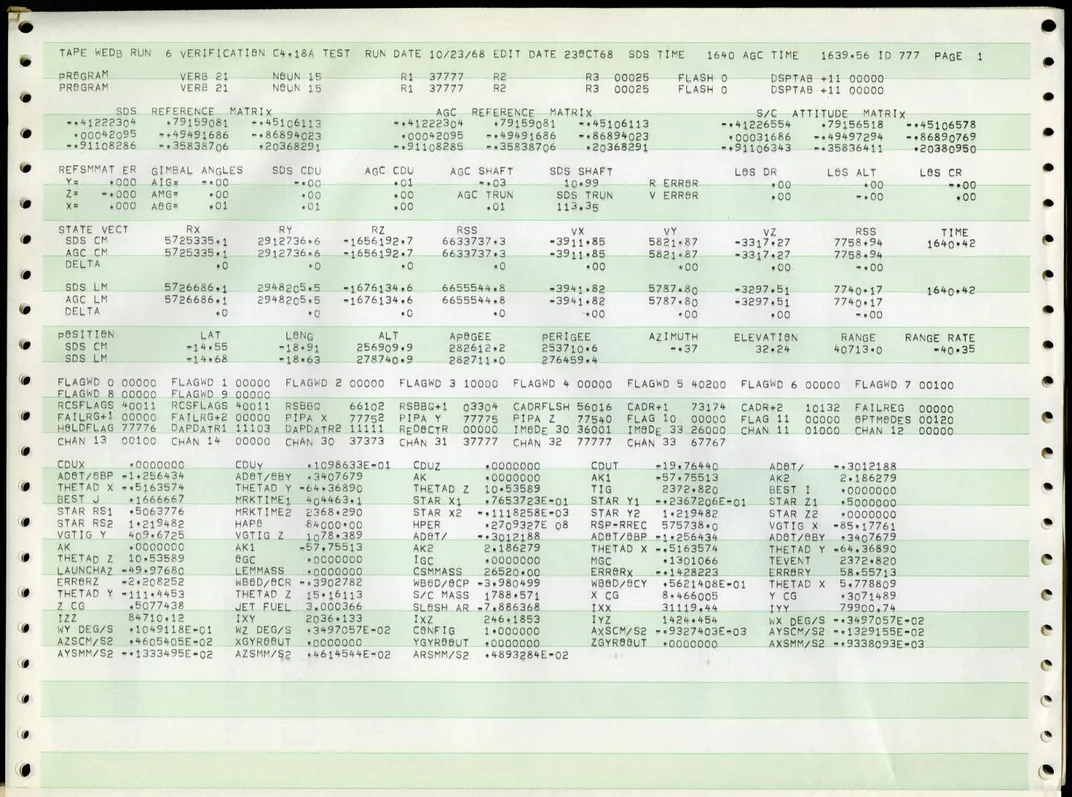

The museum holds in its collections the Apollo Flight Guidance Computer Software Collection created by Hamilton. The archival material includes printout sheets, known as “the listings,” which show results of guidance equation calculations. When the computer’s output identified no problems, software engineers would “eyeball” the listings, verifying that no issues required attention.

Once everything looked good, the code was sent to a Raytheon factory, where mostly women—many of them former employees of New England textile mills—wove copper wires and magnetic cores into a long “rope” of wire. With coding written in ones and zeroes, the wire went through the tiny magnetic core when it represented a one, and it went around the core when it represented a zero. This ingenious process created a rope that carried software instructions. The women who did the work were known as LOL, Hamilton told Ceruzzi, not because they were funny; it was short for “little old ladies.” Hamilton was called “rope-mother.”

The rope compensated for the Apollo computers’ limited memory. The process created “a very robust system,” according to Teasel Muir-Harmony, a curator also at the Air and Space Museum and author of the new book, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects. "That was one of the reasons why the Apollo Guidance Computer worked flawlessly throughout every single mission.”

A math lover from an early age, Hamilton transformed that affinity, becoming an expert in software writing and engineering following her departure from college. When her husband was attending law school at Harvard in 1959, she took a job at MIT, learning to write software that would predict the weather. A year later, she began programming systems to locate enemy aircraft in the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) program.

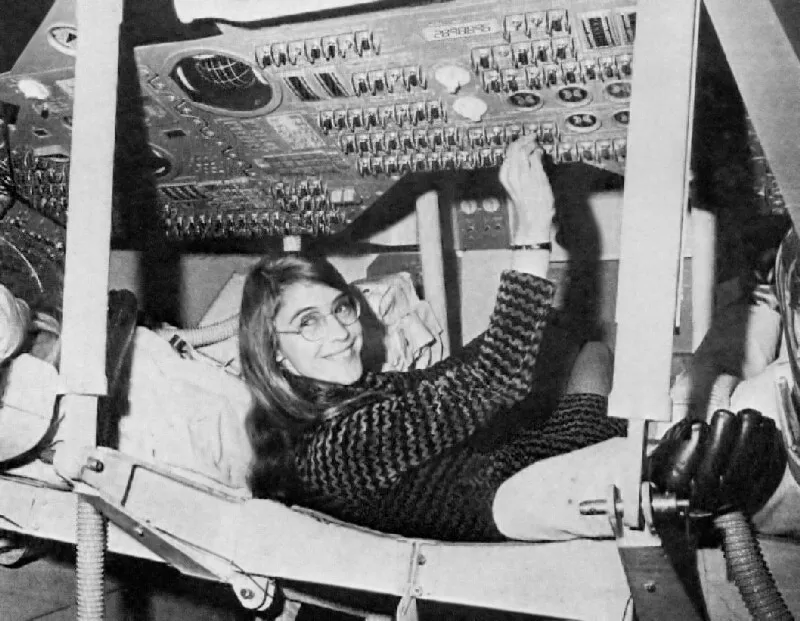

It was in the mid-1960s that Hamilton heard that MIT “had announced that they were looking for people to do programming to send man to the moon, and I just thought, ‘Wow, I’ve got to go there.’” She had planned to begin graduate school at Brandeis University for a degree in abstract math, but the U.S. space program won her heart. Thanks to the success of her work at SAGE, she was the first programmer hired for the Apollo project at MIT. In 1965, she became head of her own team at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory (later known as Draper Laboratory), which was dedicated to writing and testing software for Apollo 11’s two 70-pound computers—one aboard the command module, Columbia, and one aboard the lunar module, Eagle.

“What I think about when I think about Margaret Hamilton is her quote that 'there was no choice but to be pioneers,' because I think that really embodies who she was and her significance in this program,” Muir-Harmony says. “She was a pioneer when it came to development of software engineering and. . . . a pioneer as a woman in the workplace contributing to this type of program, taking on this type of role.”

Then, as now, most software engineers were male, but she never let that stand in her way. “She has this mentality that there should be equal rights and equal access. And it wasn’t about men and women. It was about people being able to pursue the kinds of jobs they want to pursue and take on the challenges they want to take on,” Muir-Harmony says. “She was also really expansive as a programmer, coming up with solutions for problems, very innovative, very outside-the-box thinking. That, I think, is reflected in her career choices and the work she did in the lab.”

In a bid to make software more reliable, Hamilton sought to design Apollo’s software to be capable of dealing with unknown problems and flexible enough to interrupt one task to take on a more important one. In her search for new ways to debug a system, she realized that sound could serve as an error detector. Her program at SAGE, she noted, sounded like a seashore when it was running. Once, she was awakened by a colleague, who said that her program “no longer sounded like a seashore!” She rushed into work eager to find the problem and to start applying this new form of debugging to her work.

As a working mother, she took her young daughter to the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory with her at night and on weekends. One day, her daughter decided to “play astronaut” and pushed a simulator button that made the system crash. Hamilton realized immediately that the mistake was one that an astronaut could make, so she recommended adjusting the software to address it, but she was told: “Astronauts are trained never to make a mistake.”

During Apollo 8’s moon-orbiting flight, astronaut Jim Lovell made the exact same error that her young daughter had, and fortunately, Hamilton’s team was able to correct the problem within hours. But for all future Apollo flights, protection was built into the software to make sure it never happened again. Over time, Hamilton began to view the whole mission as a system: “part is realized as software, part is peopleware, part is hardware.”

Hamilton’s work guided the remaining Apollo missions that landed on the moon as well as benefitting Skylab, the first U.S. space station, in the 1970s. In 1972, she left MIT and started her own company, Higher Order Software. Fourteen years later, she launched another company, Hamilton Technologies, Inc. At her new firm, she created Universal Systems Language, another step in making the process of designing systems more dependable.

NASA honored Hamilton with the NASA Exceptional Space Act Award in 2003, acknowledging her contributions to software development and granting her the biggest financial prize that the agency had ever awarded to one person until that time—$37,200. In 2016, President Barack Obama awarded her the Medal of Freedom, noting that “her example speaks of the American spirit of discovery that exists in every little girl and little boy who know that somehow to look beyond the heavens is to look deep within ourselves.”

Hamilton’s work may not be widely known to those outside the scientific community, though her achievements have been memorialized with the 2017 introduction of a Lego Margaret Hamilton action figure, part of the Women of NASA collection. It portrays Hamilton as a small, big-haired, bespectacled hero whose Apollo code stacked up to be taller than she was. The National Air and Space Museum now holds the prototypes for these action figures. Software engineers are not generally viewed as courageous action figures, but Hamilton is no stranger to the bravery required for heroism. She remembers “being fearless, even when the experts say: ‘No, this doesn’t make sense,’ they didn’t believe it, nobody did. It was something that we were dreaming of happening, but it became real.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)