Mark Segal, LGBTQ Iconoclast, Activist and Disruptor, Donates Lifetime of Papers and Artifacts

Following the 1969 Stonewall Raid, Segal built a life around protest and the quest for equal rights for minority groups

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/48/9d487f4d-343d-4cdc-b2e5-b40eeda4ae12/ac1422-0000021.jpg)

Mark Segal knew from a young age that acceptance would not be handed to him—he would have to work for it. Growing up, Segal’s was the only Jewish family in South Philadelphia’s Wilson Park housing project. At age 8, in the late 1950s, he refused to sing “Onward, Christian Soldiers” at school. “Activism has always been a part of my life,” he said at a recent donation ceremony at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “Poverty, anti-Semitism—you always have to fight.”

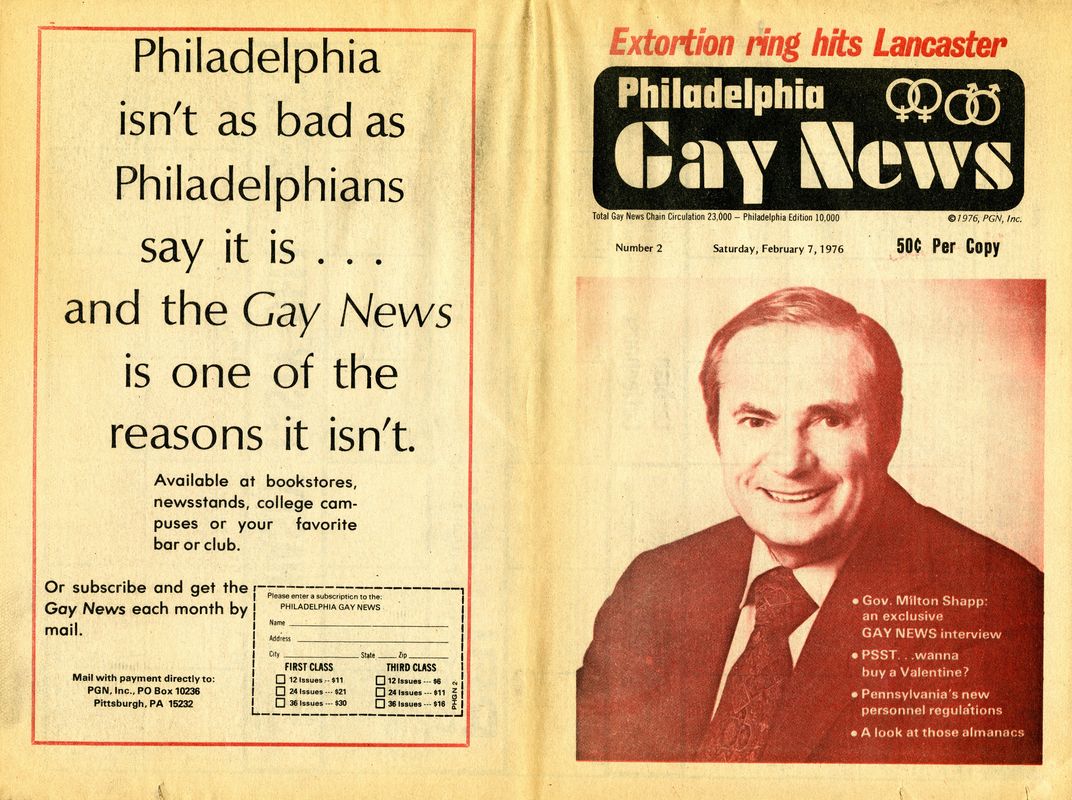

Segal carried this crusading spirit into his adult life, helping open doors for the LGBTQ community that were not imaginable a half-century ago. From organizing the first Pride March in 1970, to founding Philadelphia Gay News (PGN) and staging takeovers of nationally broadcast news programs, he established himself as one of the most influential civil rights activists in U.S. history. On May 17, 2018, in a gift to posterity, the organizer, publisher and political strategist donated 16 cubic feet of personal papers and artifacts.

Before the ceremony, attendees had the chance to view a small sample of the original documents, which the museum has archived and made available to researchers online.

Some, such as the first state-issued Gay Pride Proclamation, are triumphant declarations of progress. “One of the least understood minority groups in this state is that group of men and women who comprise the Gay Liberation Movement,” wrote Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp in June 1976. “I hereby express my support for equal rights for all minority groups and for all those who seek social justice, and dedicate Gay Pride Week to those worthy goals.” Likewise, in a March 1996 letter from President Bill Clinton congratulating PGN on its 20th anniversary in print: “Your newspaper is a wonderful example of the proud American tradition of local publishing… Best wishes for much continued success.”

Others are harrowing testaments to the pain that Segal and his peers have endured in their decades-long struggle for equal rights. One poster, which Segal found affixed to a newspaper box, was part of a mid- to late-‘80s hate campaign against PGN. “KILL THE QUEER’S,” it reads, amongst other vicious epithets and KKK insignia.

“This type of material just doesn’t survive,” said Franklin Robinson, the museum’s archivist who processed the donation. “We’re so glad to have it, and we’re hoping it opens the floodgates to get more. These things are in boxes somewhere—we don’t want them to get thrown in a dumpster because people don’t know what they are or that they’re valuable.”

A number of artifacts were also on display. Among them, a vintage T-shirt reading “Closets are for clothes,” and a tin donation can from Christopher Street Liberation Day, which Segal helped organize in the wake of the Stonewall Riots. Held in New York City’s Greenwich Village in June 1970, it was the country’s first Pride March.

After remarks from Catherine Eagleton, the museum’s associate director of curatorial affairs, and Pennsylvania Senator Bob Casey, David Cohen set the ceremony’s lighthearted tone. Cohen, who is Comcast corporation’s senior executive vice president and chief diversity officer, has been friends with Segal for more than 30 years. “Mark Segal is a packrat,” he said, commenting on the size of the donation. “[Mark’s husband] Jason’s only comment about this was: ‘This is all they took? I thought this was going to be a house cleaning!’”

Cohen then focused on Segal’s knack for taking over live news broadcasts at a time when LGBTQ voices were omitted from mainstream media. The most famous of these TV “zaps” came when Segal and a fellow Gay Raider infiltrated Walter Cronkite’s CBS Evening News. “Using a different name and pretending to be a reporter for the Camden State Community College newspaper in New Jersey, he secured permission to watch the show from within the studio,” the New York Times wrote in December 1973. Fourteen minutes into the program, Segal took his place in front of the camera, sending his “Gays Protest CBS Prejudice” sign into the homes of 20 million Americans.

Cronkite, though, heard his message. As security wrestled Segal off the set, the legendary newsman whispered to one of his producers: “Could you get that young man’s contact information?” Less than six months later, CBS Evening News featured a segment on gay rights, setting the precedent for the increased attention that other media outlets would begin to give to the movement. “Part of the new morality of the ‘60s and ‘70s is a new attitude toward homosexuality,” Cronkite told his viewers.

Seven years ago, at Cohen’s urging, Segal became a member of Comcast and NBCUniversal's External Joint Diversity Advisory Council. “Mark’s not really a joiner of traditional institutions, but I made a case to him about the elegance of the closed circle,” Cohen said. “Start by disrupting the CBS nightly news, and then later on in your career, get to be part of an advisory council of the largest media company in the United States of America.”

Finally, Segal came on stage, signed the deed of gift, and sat down with museum curator Katherine Ott, who kept the crowd laughing. “I think this is probably one of the longest stretches of time that you’ve been quiet,” she said to Segal.

When Ott asked about Segal’s influences, he spoke at length about his grandmother, who was a suffragette early in life and later brought her grandson along while participating in the Civil Rights Movement. Segal remembers asking her, at age 9, about a “strange” guest she had at one of her dinner parties. “You’ve got to know what’s in someone’s heart and love them for that,” she replied. Segal would later realize that the woman was the first open lesbian he had ever met.

The conversation continued with Segal talking about his experiences working with Pennsylvania politicians, downplaying the gumption it took to reach compromises with the movement’s antagonists. In 1974, Segal asked Congressman Robert Nix to support the Equality Act, which would amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to include protections that ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and sex. Nix, Pennsylvania’s first black congressman, wondered why he should back such a cause. “When I was 13, my grandmother had me walking around City Hall with pickets,” Segal responded. “You were there—we talked. I was a part of your movement; I now need you to be a part of our movement.” Nix became the first black legislator to sign onto the bill, which to this day has not been passed.

Segal also touched on the LGBTQ publishing industry, which has seen explosive growth since he helped pioneer it by founding PGN 42 years ago. Highlighting local stories that national outlets overlook is crucial, he said. PGN has spent 13 years, for example, covering the story of Nizah Morris, a transgender woman who sustained a fatal head wound while in the custody of Philadelphia police officers in December 2002. The paper is currently suing the mayor and district attorney, in the hopes that their offices will release documents related to the case.

Segal feels that this persistence holds a valuable lesson for the young people who are still fighting for a more just world. “Don’t be afraid to be controversial,” he said. “That’s what makes community dialog.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AdamGreenScreenSq.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AdamGreenScreenSq.jpg)