Martin Puryear’s Hometown Retrospective Brings the World Renowned Artist Back to His Roots

After treks to Africa, Scandinavia and Japan, Puryear’s works go on display at the Smithsonian, where he first developed his curiosity for world cultures

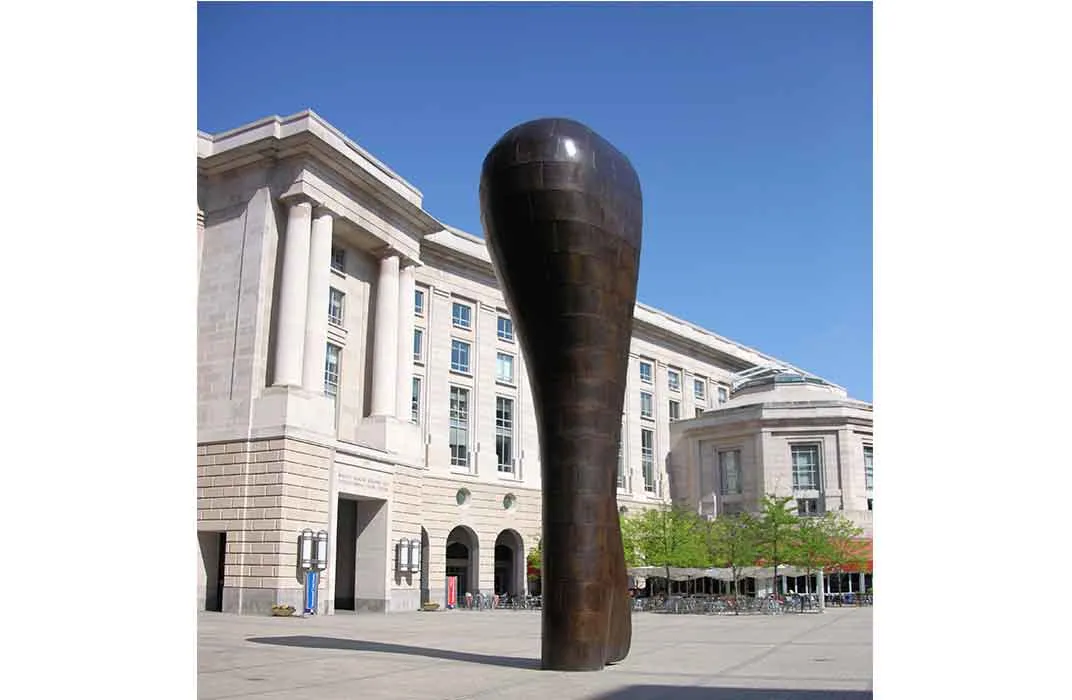

Each day, thousands of people pass Bearing Witness, Martin Puryear’s monumental 40-foot sculpture at Washington D.C.’s Federal Triangle. Thousands of others will delight at a temporary sculpture just as tall this summer at New York City’s Madison Square Park titled Big Bling.

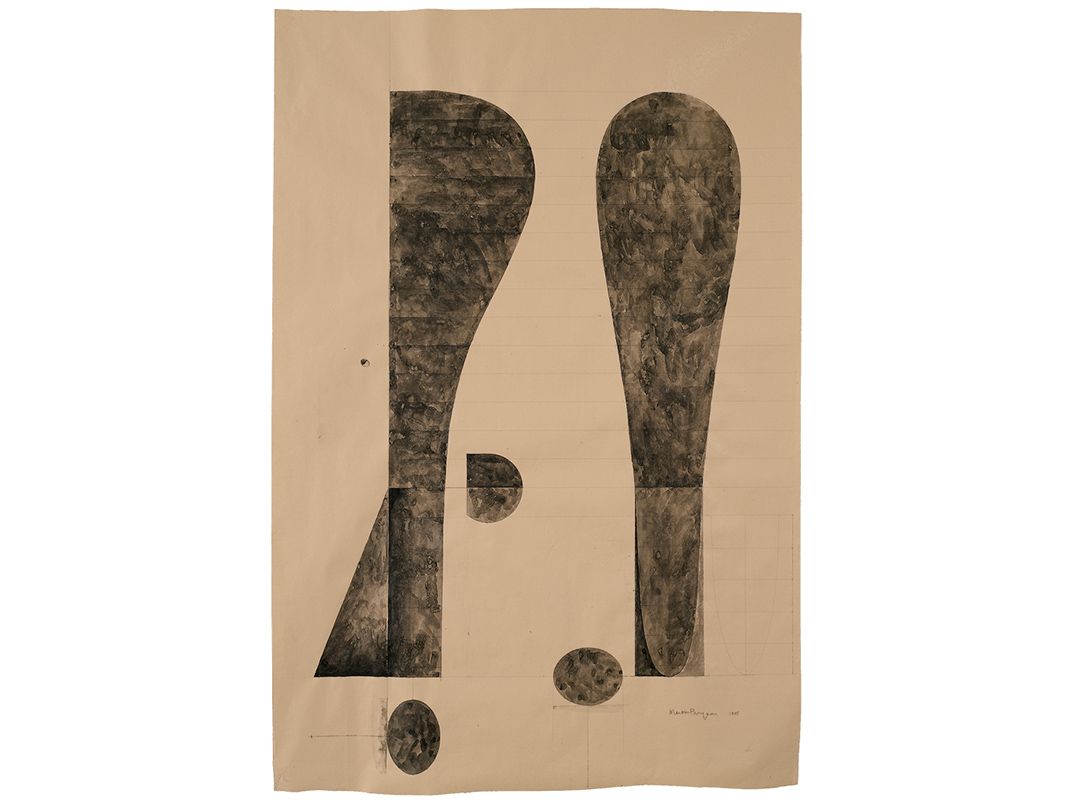

The thought process behind those elegant, sometimes enigmatic, works become evident in a major show this summer in the artist’s birth city.

“Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions,” which just opened at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., connects Puryear’s craftsmanlike sculptures (and a few maquettes of public work) with dozens of drawings, prints and etchings.

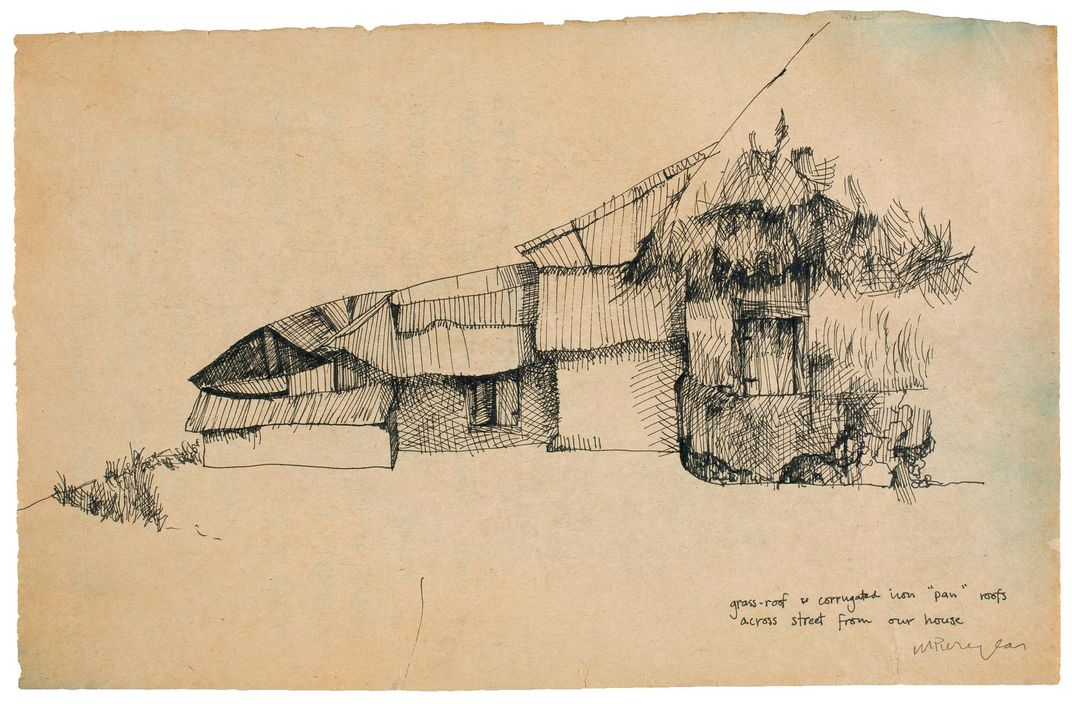

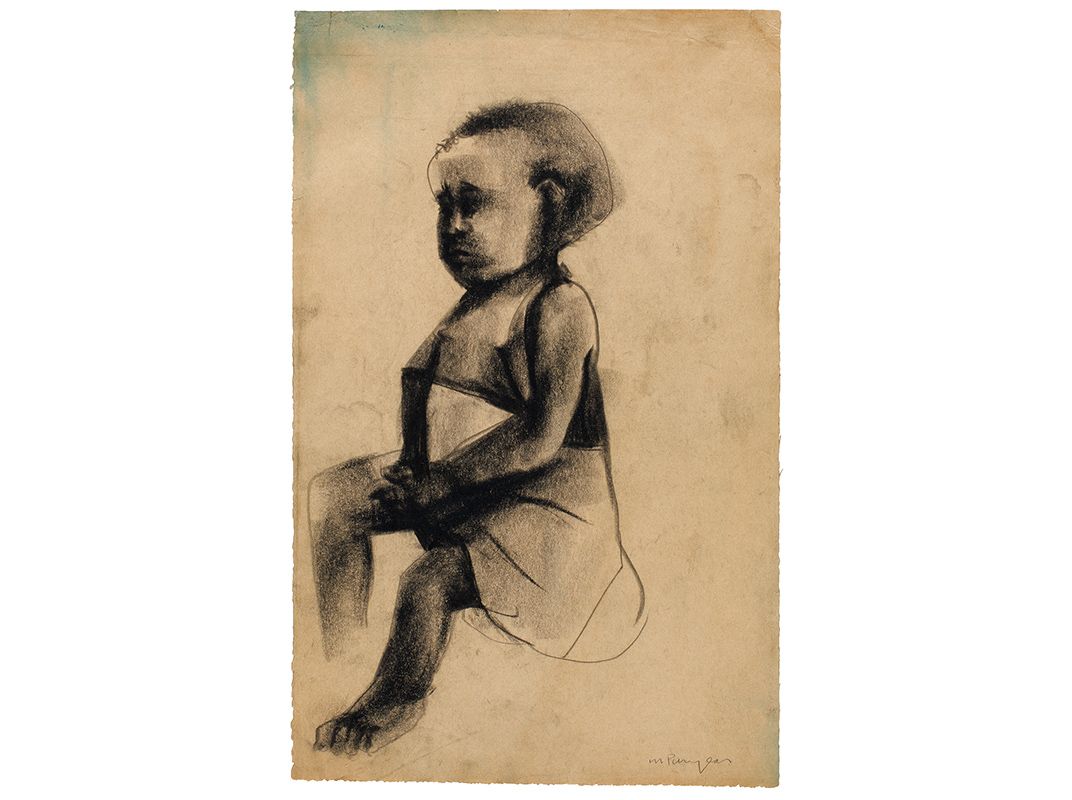

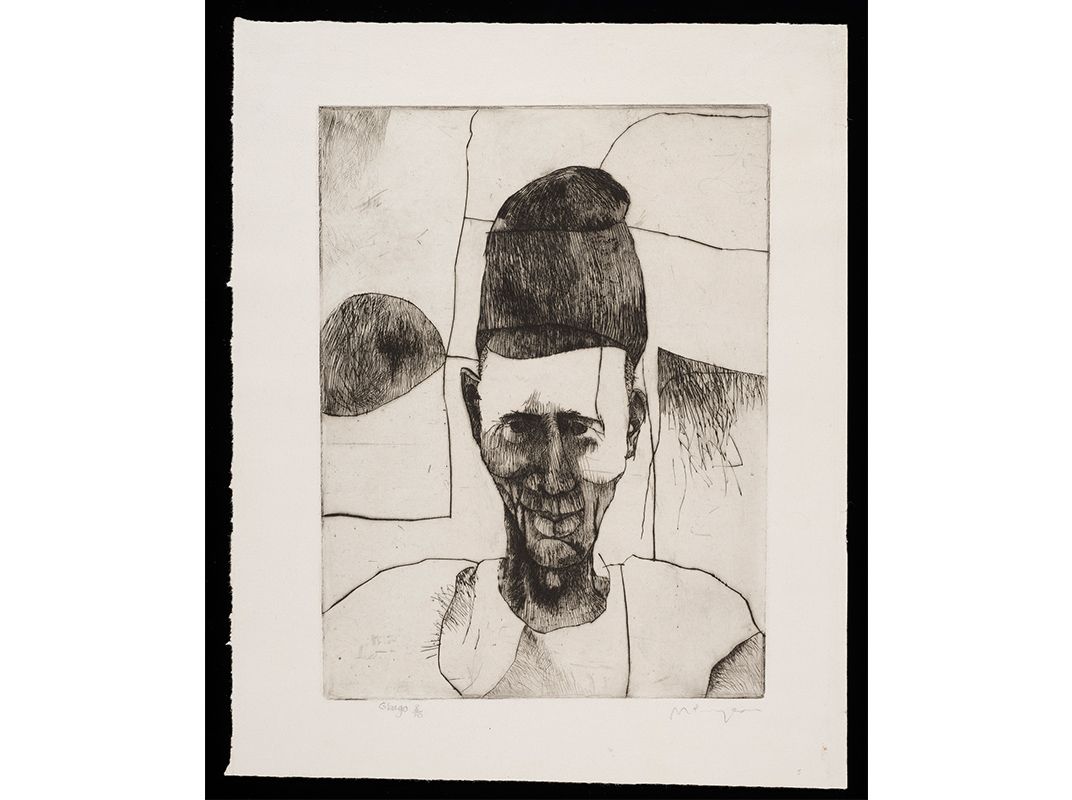

Some of the two dimensional work goes back 50 years, when the young artist was learning his craft during two years in the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone and another two at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm in the mid to late 1960s.

There, shapes of thatched roofs and African faces were first sketched and sent home in lieu of photographs, says Joann Moser, the recently retired Smithsonian American Art Museum curator who helped assemble the show. “He didn’t have a camera with him in Sierra Leone.”

Many of the pieces, from Puryear’s own collection, had never been seen publicly before this show, which was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and also was exhibited at New York’s Morgan Library and Museum. “For someone known for public monuments, this is a rare look at private works that he made for himself, or for his family,” Moser says.

Many of the early paper pieces needed extensive conservation, Moser said. And even so, some of the works, such as a 1965 graphite drawing Gbago, has traces of blue on it because the portfolio in which it was placed got wet.

Still, it’s remarkable there is as much work as there is in the show, considering that Puryear’s Brooklyn studio was destroyed by fire in 1977, the same year the artist had his first solo show, at Washington, D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery of Art.

While there were 100 pieces in the Chicago exhibition, and considerably fewer at the Morgan Library because of space limitations, the Smithsonian exhibition is in the middle, with 72 works, including 13 from the museum’s own collection.

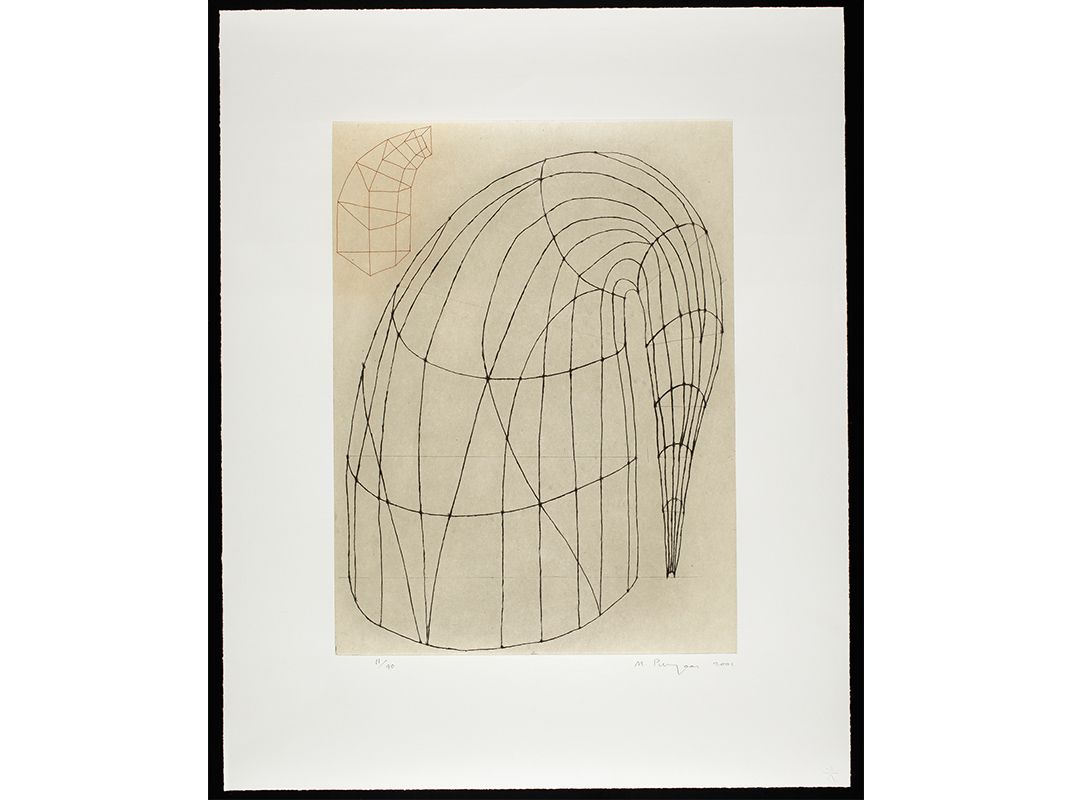

Most prominent among them is Bower, a bent wood sculpture of fanning slats that have a similar geometry found in some of his swirling drawings done decades later, and a swirl that suggests a recurring shape in his work, echoing from the distinctive red “Libertie” caps worn in France.

“This gentle notch here is something that reappears when he explores the Phygian cap, the symbol of liberty both in the French Revolution but also a symbol for abolition throughout the 19th century,” says Karen Lemmey, the Smithsonian American Art Museum curator of sculpture who coordinated the exhibition in Washington, the final stop for the national tour.

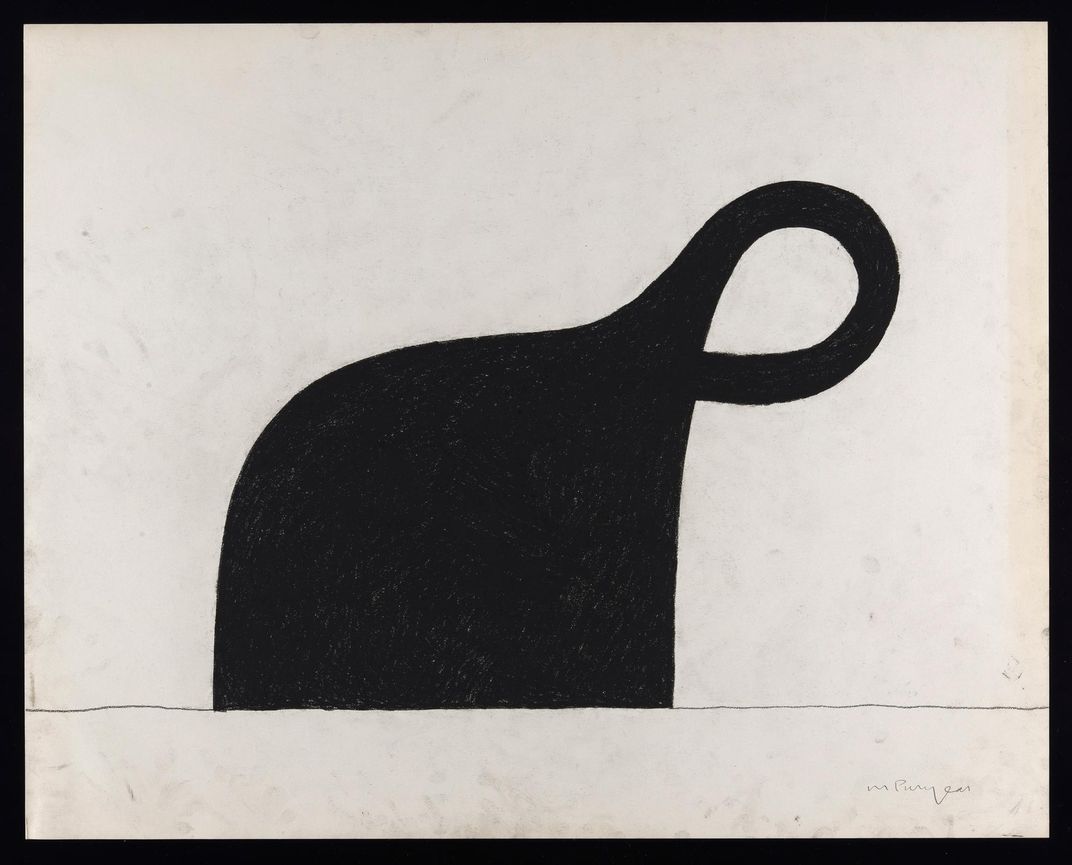

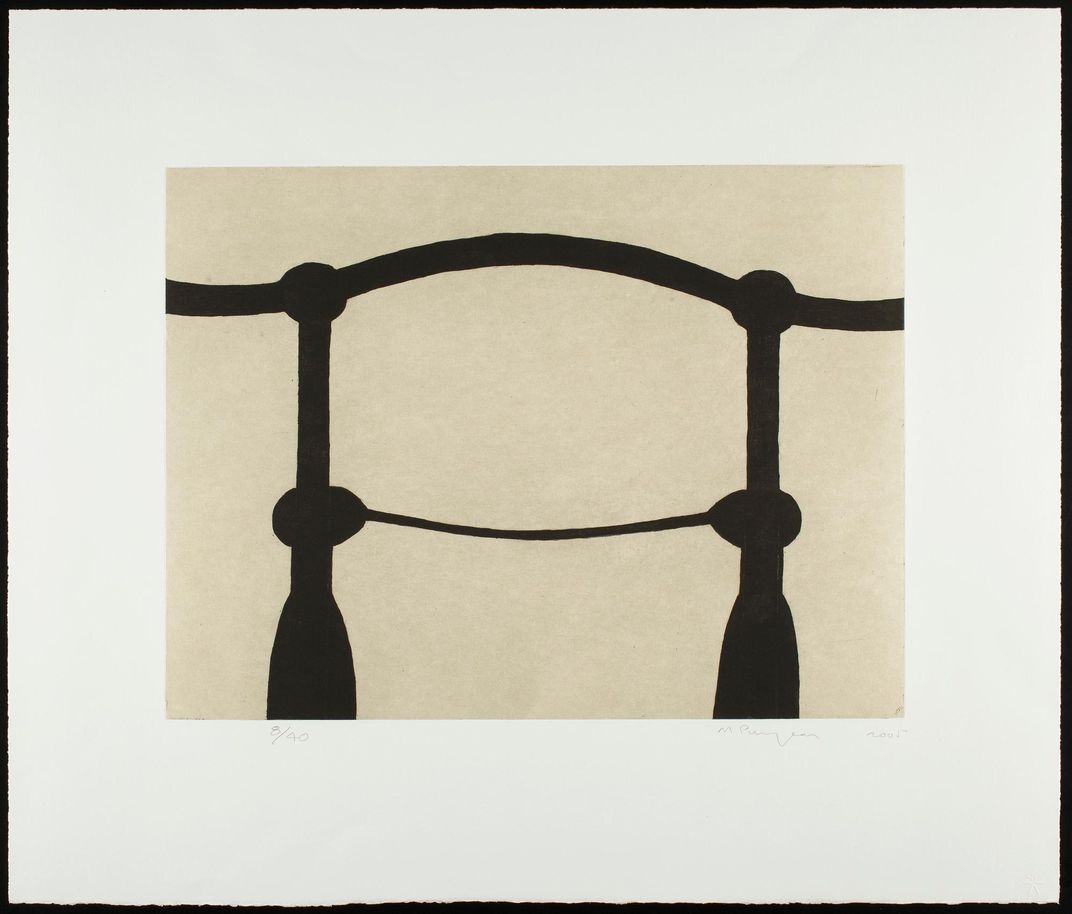

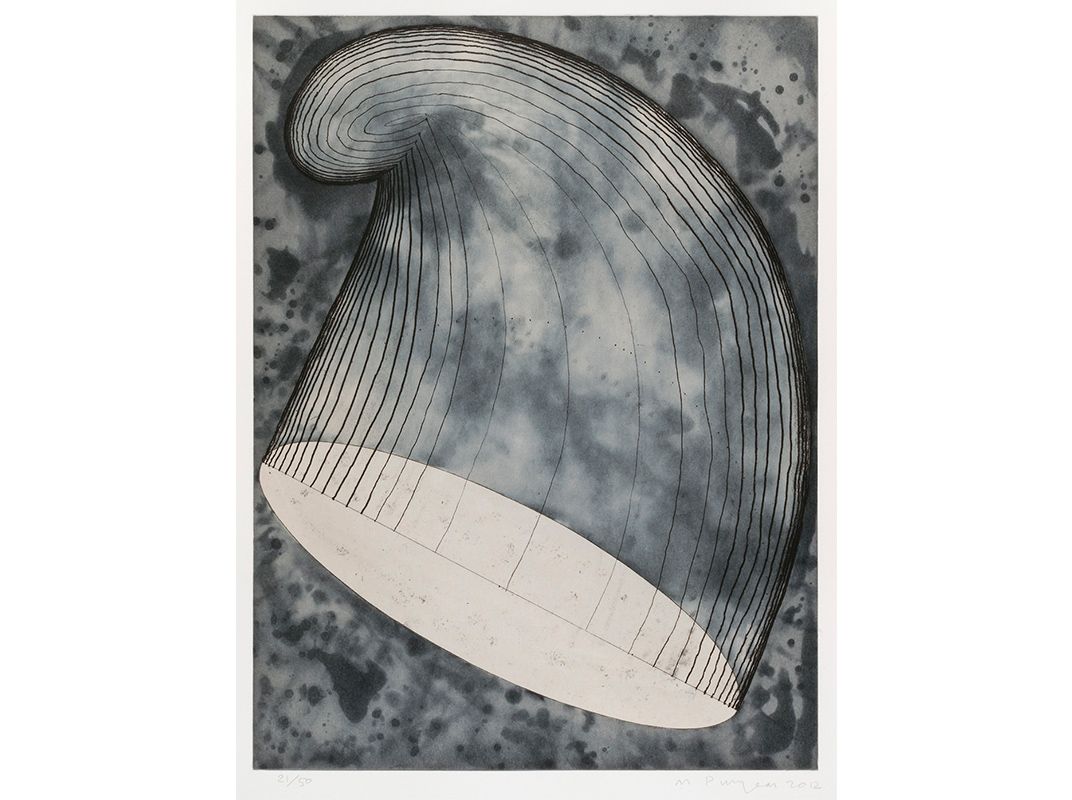

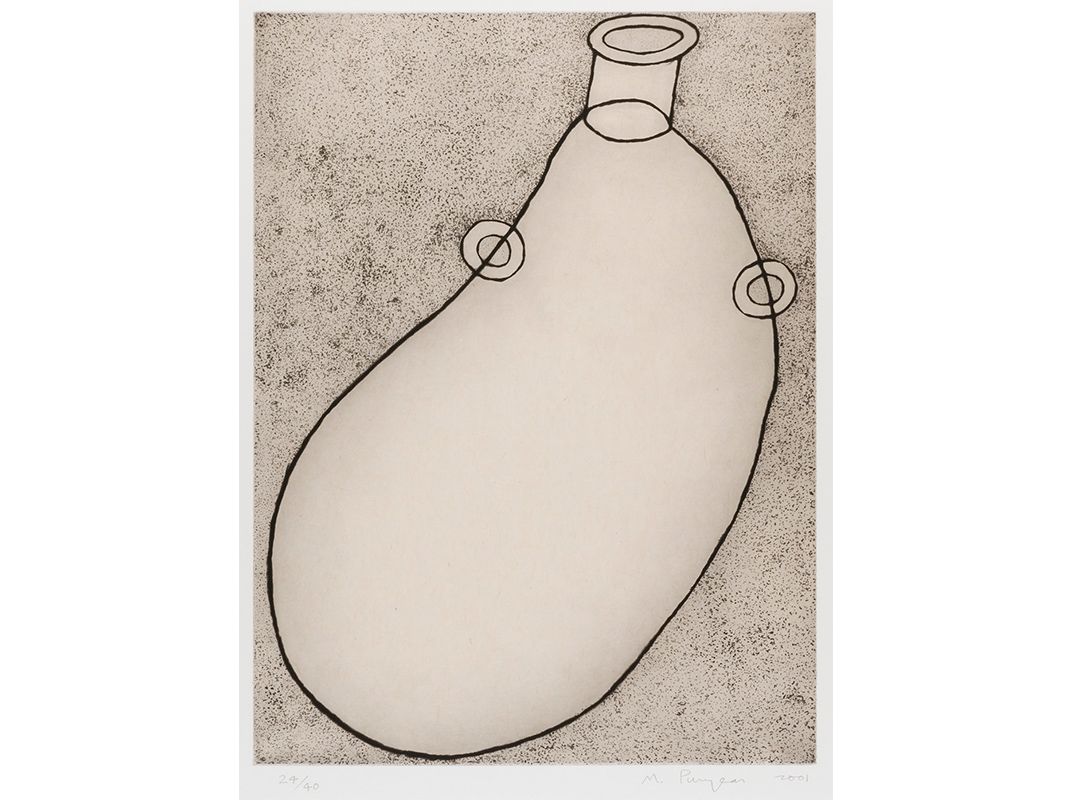

The bump on Puryear’s 2012 etching Phrygian echoes not just the notch in the 1980 Bower, but also the swirl in an Untitled 2003 drawing.

“It’s wonderful to be able to look at a work from 1980 and then look at the print, recently acquired for the collection but made in 2012, across his span of decades and from a 3D work to a 2D work, he’s never quite let go of the idea,” Lemmey says.

As such, she ditched the usual chronological display of an artist’s work.

“He didn’t work in a linear manner,” Lemmey says. “The word he uses to describe his practice is spiral, and you’ll see in every form that if you look at the date, that you’ll go backward and forward in time to see how these shapes take form on paper and in sculpture.

“This way of exhibiting his work really reveals his creative process,” she says, “which to me is important because he can be an enigmatic artist. What emerges here is a visual vocabulary, a language of his own making, as he realizes these forms in 2D and 3D.”

It may not help that a number of Puryear’s abstract works are untitled.

“He’s very reticent about explaining things,” Lemmey says. “Some of his works are untitled but when he does give a title, it opens up rather than shuts down the discourse.

“He recently said at Madison Square Park at the dedication of Big Bling,” she added, “he said ‘I trust people’s eyes. I trust people’s imaginations. I trust my work to declare itself to the world.’”

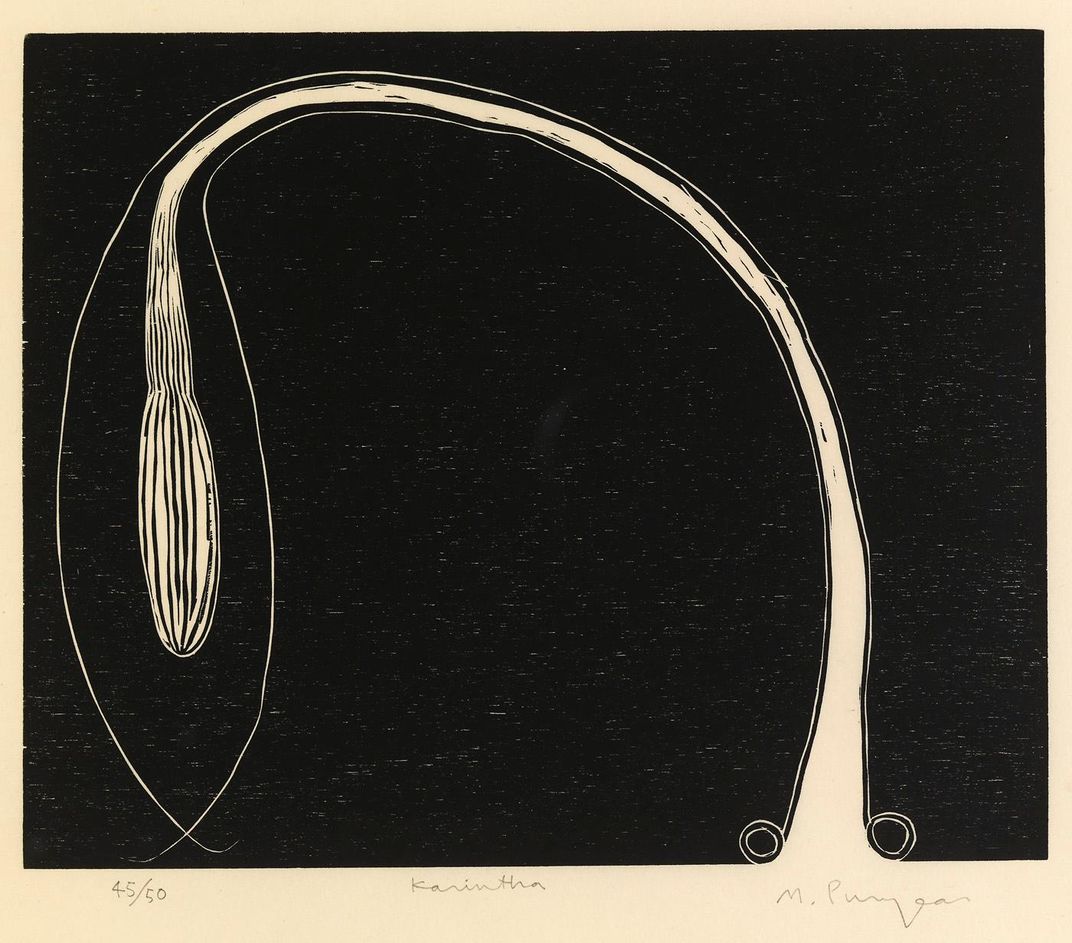

Among the work displayed from the Smithsonian collection are five of six woodcuts Puryear created to illustrate a 2000 edition of poet Jean Tooomer’s 1923 “Cane,” a notable highlight of the Harlem Renaissance that also spoke to the artist’s experience.

“Very few of his works made reference to his African-American heritage,” Moser says. “In his book he is really acknowledging it publicly.”

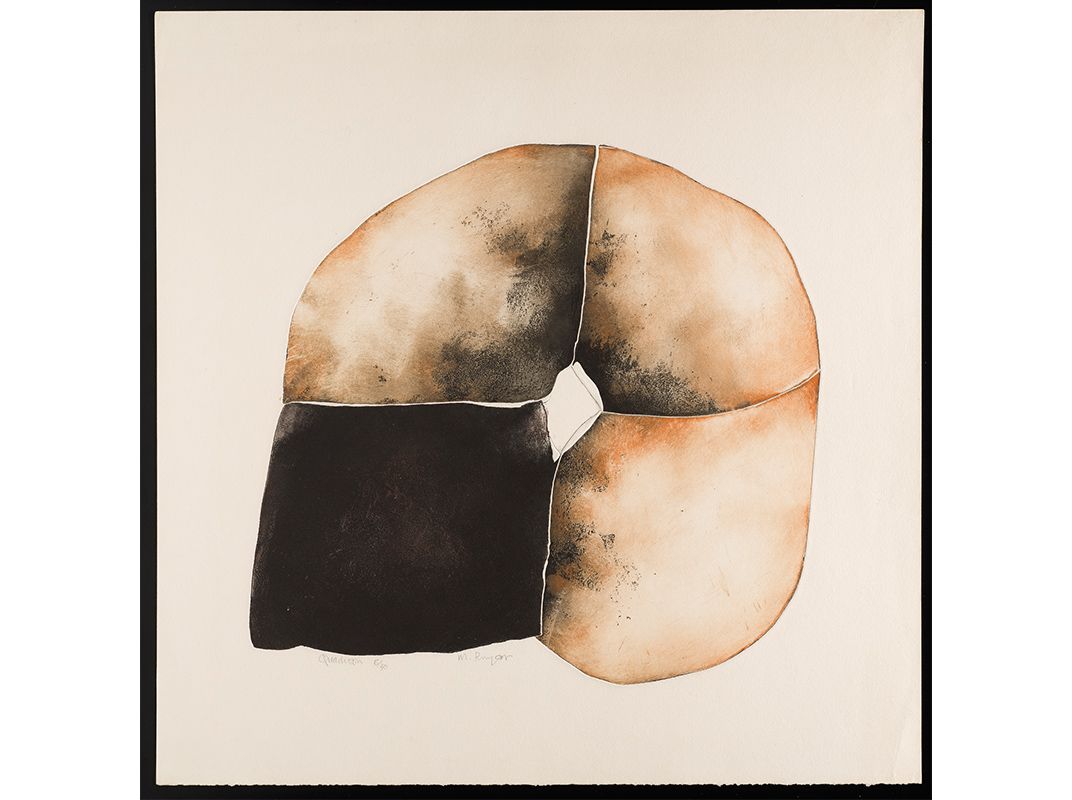

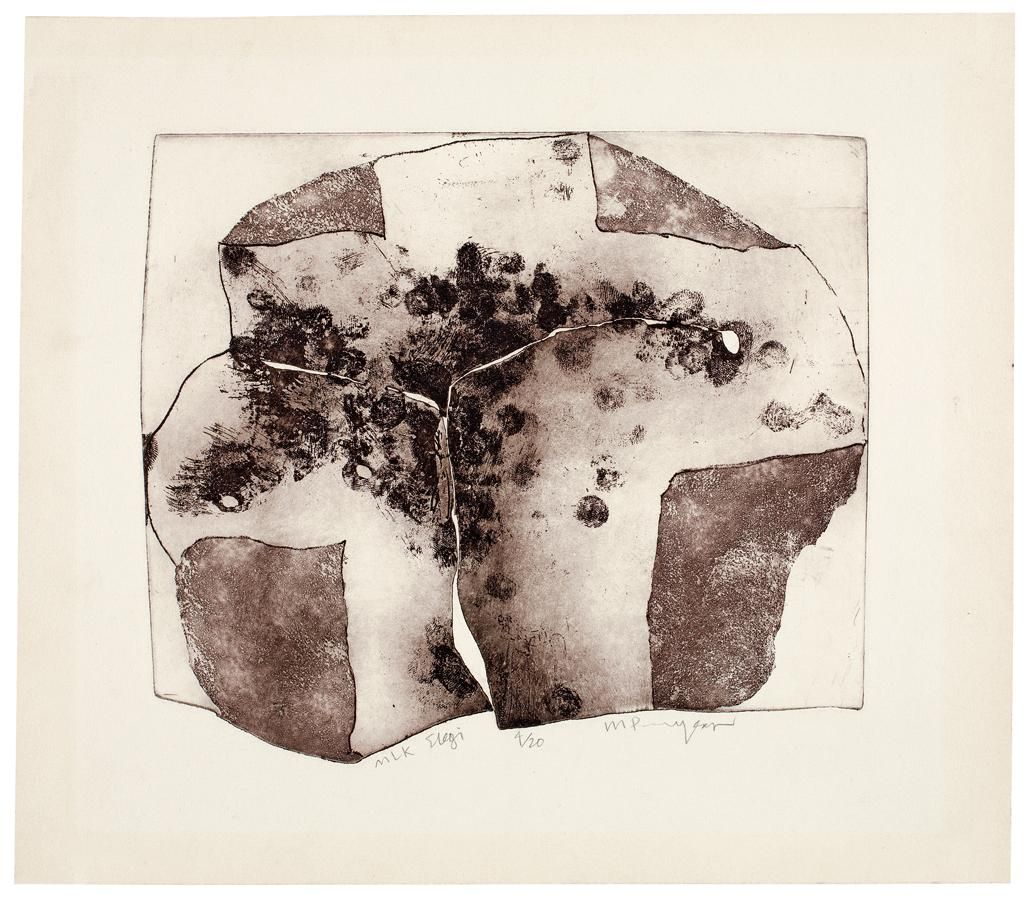

Similarly, works like the 1966-67 Quadroon and 1968 MLK Elegi, “speak to what it must have been like for him,” Moser says, learning from abroad the assassination of Martin Luther King. “As a young African American on the outside,” she says, “he has spoken about the significance of leaving his country in these formative years and how that influenced the way he saw his country.”

Puryear had a longtime interest in the human head, which is straightforward in an untitled 1996 drawing, a 2002 etching titled Profile and a pair of 2009 sculptures.

But the stylized head facing down, as depicted in the 2008 white bronze work on display, Face Down, is also repeated in the largest piece in the show, the pine, mesh and tar work Vessel, dated from 1997 to 2002 (and its accompanying Drawing for Vessel from 1992-93).

Along those lines, the enigmatic, towering federal commission in D.C., a half mile from the museum, Bearing Witness, rather than being the “Thumb” that some people call it, can be more directly seen as a stylized version of another kind of head, the type Puryear may have first seen in the Smithsonian amid a collection of African Fang masks.

“Growing up in the District, he said he and his family really frequented the Smithsonian,” Lemmey says of Puryear. And despite his residencies in Africa, Scandinavia and Japan later in his life, “ it’s not inaccurate that his curiosity for world cultures had its roots in his growing up in the District and the Smithsonian serving as his local museum and his exposure in the 1950s to global cultures through exhibits here reappears in the work that he makes in the 90s for a federal commission.”

That in part is why “we feel very strongly” about the Smithsonian being the closing stop of the exhibition, Lemmey says, “because it was his home town.”

The opening of the Smithsonian exhibition came within days of both the unveiling of his 40-foot temporary sculpture Big Bling at New York’s Madison Square Park (the maquette of which is in the show), and the presentation to Puryear of the third Yaddo Artist Medal (after ones given in previous years to Laurie Anderson and Philip Roth)—as well as the artist’s 75th birthday.

“He’s having a moment,” Lemmey says.

And yet, in reaching such milestones, the artist, who lives and works in New York’s Hudson Valley, “is constantly thinking of the future,” she says.

Agreeing to this retrospective now, Lemmey says, “gives him an opportunity to share what he once considered private. I think that’s indicative of a mature artist arriving at a point in one’s career and saying, OK, it’s time.”

“Martin Puryear: Multiple Dimensions” continues through September 5 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Eighth and F Streets NW, Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)