Meet the Female Inventor Behind Mass-Market Paper Bags

A self-taught engineer, Margaret Knight bagged a valuable patent, at a time when few women held intellectual property

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/f4/62f49126-5ab2-48f7-9576-30aa252f5142/margaretknight.jpg)

It’s natural to think about the processes that produced the food in your daily sack lunch, but have you ever stopped to consider the manufacturing techniques behind the sack itself? The flat-bottomed brown paper bags we encounter constantly—in the lunch context, at grocery stores, in gift shops—are as unassuming as they are ubiquitous, but the story underlying them deserves recognition. At the center of it is a precocious young woman, born in Maine on the heels of the Industrial Revolution and raised in New Hampshire. Her name is Margaret Knight.

From her earliest years, Knight was a tireless tinkerer. In a scholarly article titled “The Evolution of the Grocery Bag,” engineering historian Henry Petroski mentions a few of her childhood projects, which tended to demand a certain facility for woodwork. She was “famous for her kites,” Petroski writes, and “her sleds were the envy of the town’s boys.”

With only rudimentary schooling under her belt, a 12-year-old Knight joined the ranks of a riverside cotton mill in Manchester to support her widowed mother. In an unregulated, dangerous factory setting, the preteen toiled for paltry wages from before dawn until after dusk.

One of the leading causes of grievous injury at the mill, she soon observed, was the propensity of steel-tipped flying shuttles (manipulated by workers to unite the perpendicular weft and warp threads in their weaves) to come free of their looms, shooting off at high velocity with the slightest employee error.

The mechanically minded Knight set out to fix this, and before her thirteenth birthday devised an original shuttle restraint system that would soon sweep the cotton industry. At the time, she had no notion of patenting her idea, but as the years went by and she generated more and more such concepts, Knight came to see the moneymaking potential in her creativity.

As Petroski explains, Knight departed the brutal mill in her late teens, cycling through a number of technical jobs to keep her pockets and her mind well-fed. In time, she became adept in a formidable range of trades, equally comfortable with daguerreotypes as she was with upholstery. What cemented—or should have cemented—her place in the history books was her tenure at the Columbia Paper Bag company, based in Springfield, Massachusetts.

At the bag company, as with most places she spent appreciable time, Knight saw opportunities for improvement. Instead of folding every paper bag by hand—the inefficient and error-prone task she was charged with—Knight wondered if she might instead be able to make them cleanly and rapidly via an automated mechanism.

“After a while,” Petroski writes, “she began to experiment with a machine that could feed, cut, and fold the paper automatically and, most important, form the squared bottom of the bag.” Prior to Knight’s experiments, flat-bottomed bags were considered artisanal items, and were not at all easy to come by in common life. Knight’s idea promised to democratize the user-friendly bags, ushering out the cumbersome paper cones in which groceries were formerly carried and ushering in a new era of shopping and transport convenience.

By the time she had built a working model of her elegant paper-folding apparatus, Knight knew she wanted to go the extra step and secure a patent on her creation. This was considered a bold move for a woman in the 19th century, a time when a vanishingly small percentage of patents were held by women (even allowing for those women who filed under male aliases or with sex-neutral initials).

Even in contemporary America, where women have full property rights and hold many more positions of power in government than in the 1800s, fewer than 10 percent of “primary inventor” patent awardees are female—the result of longstanding discouraging norms.

Not only did Knight file for a patent, she rigorously defended her ownership of the bag machine idea in a legal battle with a fraud who had copied her. Having gotten a glimpse of Knight’s machine in its development phase, a man named Charles Annan decided he would try to pull the rug out from under her and claim the creation as his own.

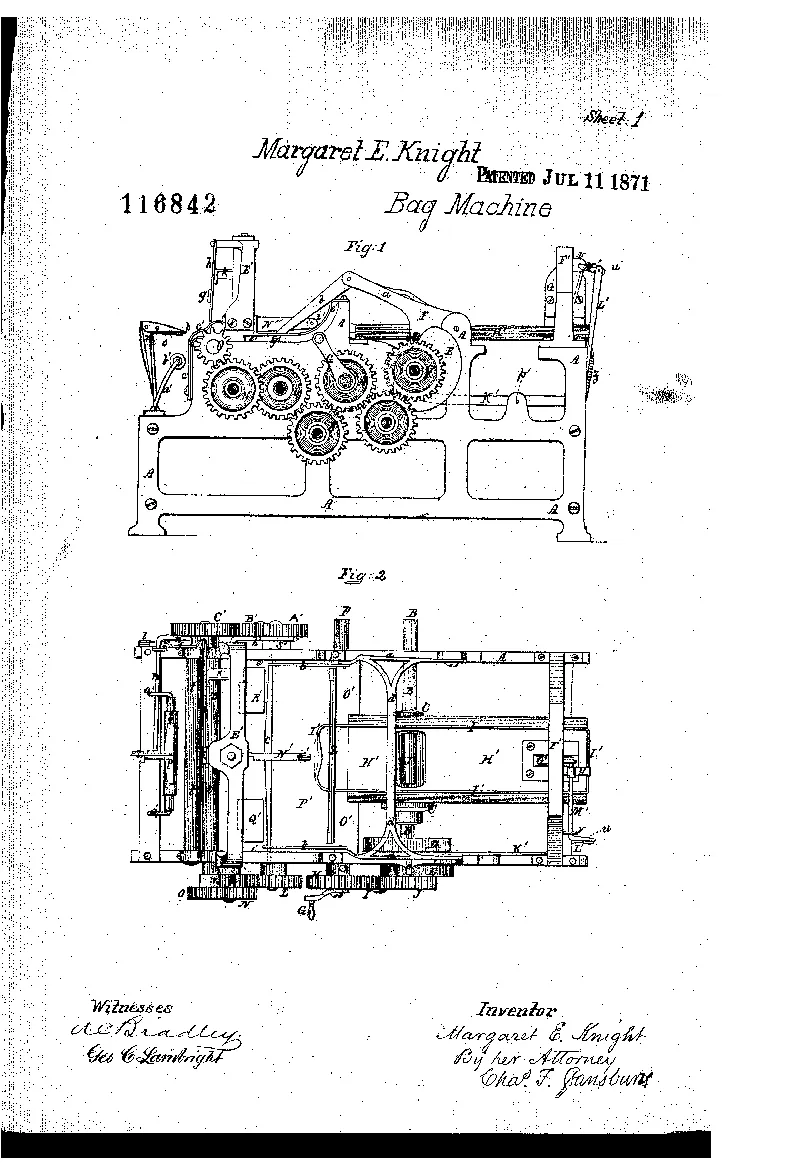

This turned out to be extremely ill-advised, as Knight, who spent a large chunk of her hard-earned money on quality legal counsel, handed Annan a humiliating courtroom drubbing. In response to his bigoted argument that no woman could be capable of designing such a machine, Knight presented her copious, meticulously detailed hand-drawn blueprints. Annan, who had no such evidence to offer himself, was quickly found to be a moneygrubbing charlatan. After the dispute was resolved, Knight received her rightful patent, in 1871.

Today, a scaled-down but fully functional patent model of Knight’s groundbreaking machine (actually an update on her original design, patented in its own right in 1879) is housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. An impressive assembly of gold-colored metal gears, springs and other parts mounted on a deep brown hardwood frame, the efficient bag-folding device, whose full-scale cousins soared into international use in the years following Knight’s efforts, offers silent, majestic testimony to the power of women to achieve in mechanics and engineering.

“Women have been involved in many activities for a long time,” says museum technology history curator Deborah Warner, who acquired the Knight model from an outside company a few decades back. “They were inventing and patenting in the 19th century, and this happens to be a woman who seems to have been particularly inventive, and bold.”

Over her prolific intellectual career, Knight would successfully file for more than 20 patents in total, running the technological gamut from combustion engines to skirt protectors. Though she managed to live more comfortably in middle and old age than in childhood, Knight was never rich by any means. Unmarried and without children, Knight—as Nate DiMeo, host of the historical podcast “The Memory Palace,” movingly explains—died alone with her achievements and a mere $300 to her name.

The implications of Knight’s eventful life were addressed in widely read ink as early as 1913 (one year before her death), when the New York Times, in what was then a refreshingly progressive move, ran a lengthy feature on “Women Who Are Inventors,” with Knight as the headliner.

Explicitly rebutting the lingering notion that women weren’t wired for innovation (“The time has come now. . . when men must look to their laurels, for the modern field is full of women inventors.”), the author of the piece calls special attention to Knight (“who at the age of seventy is working twenty hours a day on her eighty-ninth invention”), then goes on to enumerate several other similarly gifted female contemporaries. These include “Miss Jane Anderson,” who designed a bedside slipper rack, “Mrs. Norma Ford Schafuss,” who pioneered a buckle for garters, and “Mrs. Anita Lawrence Linton,” a vaudeville performer who fashioned a realistic “rain curtain” for use in dramatic stage productions.

No doubt many female inventors of the early 1900s—and later—were spurred on by Knight’s courageous example. Warner sees in the story of the talented and tenacious Knight an enduring source of inspiration for anyone with original ideas looking to better the world around them. “Someone tried to steal her design, and she sued him and won,” Warner stresses, “and she made money out of her invention too. She was a tough lady!”

Humble paper bags, which to this day are manufactured using updated versions of Knight’s “industrial origami” machine (Petroski’s term), remind us just how much one resolute woman was able to achieve, even when the cards were stacked against her. “She’s a terrific hero,” says Warner, “and a role model.”

Editor's Note, March 16, 2018: A photo originally included in this story was identified as an image of Margaret Knight, but additional research indicates that the woman depicted is unlikely to be her. We have removed the photo in question to avoid further confusion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)