Meet Lena Richard, the Celebrity Chef Who Broke Barriers in the Jim Crow South

Lena Richard was a successful New Orleans-based chef, educator, writer and entrepreneur

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/dd/deddc11f-f01a-4c09-9e46-77c05f579058/lena-richard-on-set-close-upcourtesy-newcomb-archive.jpg)

In 1949, nearly a year after New Orleans’ WDSU-TV went live for the first time, Lena Richard, an African American Creole chef and entrepreneur, brought her freshly prepared dishes to a family-style kitchen TV set and took to the screen to film her self-titled cooking show—the first of its kind for an African American.

“Her reputation was very fine,” says Marie Rhodes, Richard’s daughter and sous chef. “Everybody used to call her Mama Lena.”

The show, titled “Lena Richard’s New Orleans Cook Book” was one of the earliest offerings on the station, and became so popular that WDSU-TV began airing her show twice weekly on Tuesdays and Thursdays. While the program welcomed a racially mixed audience, the majority were white middle- and upper-class women, who leaned on Richard’s culinary expertise for all things Creole.

“Richard’s ability to share her recipes on TV—in her own words, and as the star of her own program—was an important and fairly exceptional departure within the media culture at the time,” says Ashley Rose Young, a historian and curator at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, who has done extensive research into the life and legacy of the New Orleans chef.

Sidedoor's "America's Unknown Celebrity Chef" Tells the Story of Lena Richard

Mama Lena was the “Martha Stewart” of New Orleans—a trained chef, acclaimed cookbook author, restaurant and catering business owner, frozen food entrepreneur, TV host and cooking school teacher. With skillful élan, Richard artfully tore down racial and economic barriers in the heart of the Jim Crow South, improving the livelihoods of current and future African Americans in her community. And while Mama Lena proved to be a mid-century force of nature across the food industry, today, her story remains largely forgotten by both New Orleans and the nation.

To mark this year’s centennial celebration of women’s suffrage, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is highlighting Richard’s culinary achievements in a new Sidedoor podcast, as well as in a new upcoming display within the museum's “American Enterprise” exhibition. “The Only One in the Room” features seven other female entrepreneurs and businesswomen, who broke barriers and found themselves at the helm of their respective industries. (The museum is currently closed to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19.)

Born in New Roads, Louisiana, in 1892, Richard began her culinary career at the age of 14, assisting her mother and aunt as a part-time domestic worker for the Vairins, a prominent New Orleans family. Richard was drawn to the wealthy family’s kitchen. Noticing the budding chef’s natural talent and curiosity for cooking, the matron of the family, Alice Vairin, set aside a day each week for Richard to experiment with unique dishes. Eventually, after eating one of the teenager's prepared dinners, Vairin hired the young cook full-time and increased her pay.

Soon after, Vairin signed Richard up for local cooking school classes, before sending her north for eight weeks to Boston’s prestigious Fannie Farmer cooking school. In 1918, she was likely the only woman of color in the program. “It’s not that the [Fannie Farmer] cooking school wouldn’t admit women of color,” Young says. “But if they did, they first sought permission from every single white woman in that class.”

Richard quickly found her culinary skills to be more advanced than those of her classmates. “When I got ‘way up there, I found out in a hurry they can’t teach me much more than I know,” she later recalled in an interview. “When it comes to cooking meats, stews, soups, sauces and such dishes we Southern cooks have Northern cooks beat by a mile. That’s not big talk; that’s honest truth.”

Richard’s peers weren’t shy about asking for advice. Throughout the eight-week course, her white classmates looked to the New Orleans chef for advice on local Southern classics. “I cooked a couple of my dishes like Creole gumbo and my chicken vol-au-vent, and they go crazy, almost trying to copy down what I say,” Richard said. “I think maybe I’m pretty good, so someday I’d write it down myself.” The praise from her classmates sparked inspiration; her Creole recipes, she began to realize, would be useful to other local New Orleans chefs and to those unfamiliar with the cuisine.

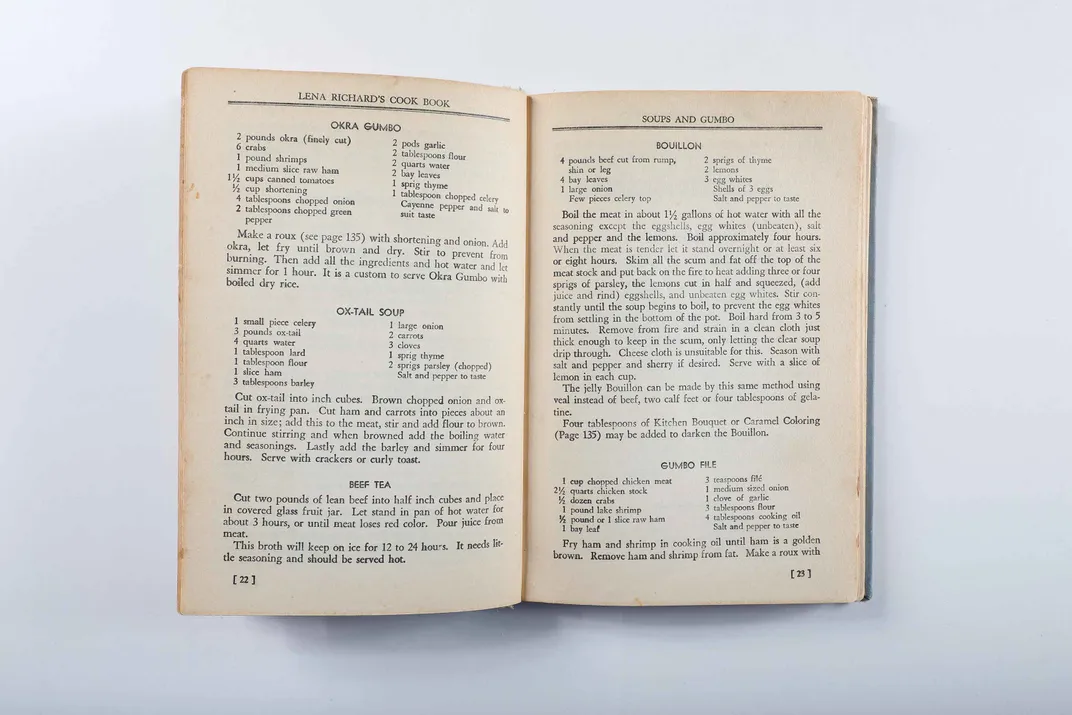

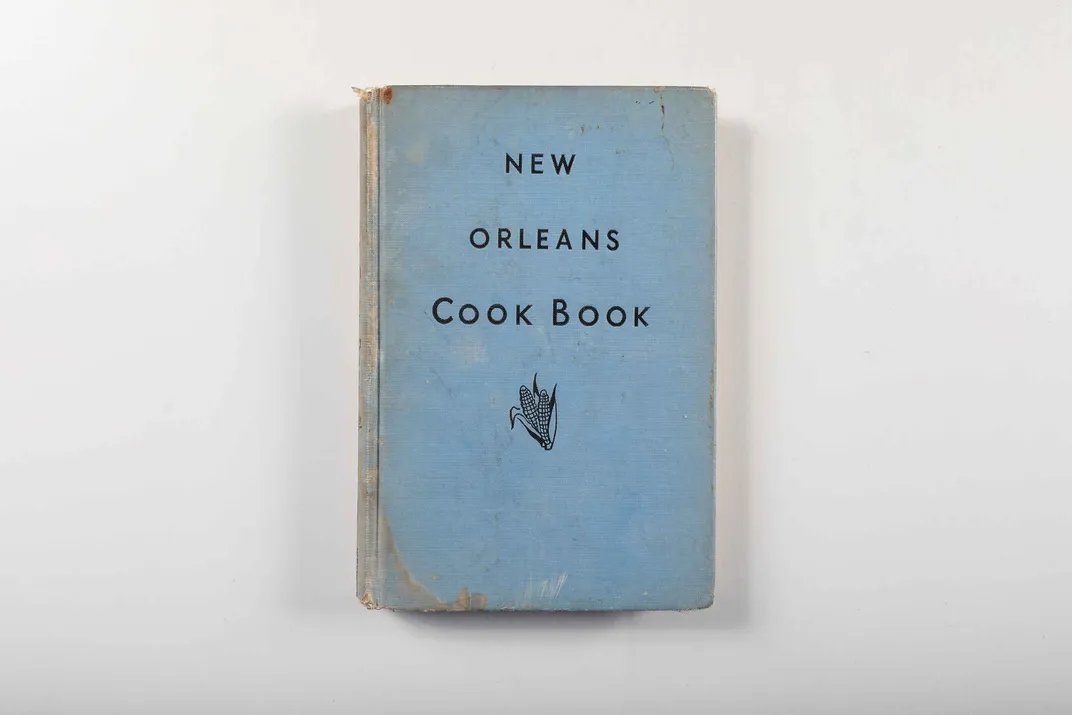

The 1939 self-publication of the first version of her more than 300-recipe collection was titled Lena Richard’s Cook Book. Shortly after, a New York Herald Tribune food writer Clementine Paddleford and the renowned food critic James Beard endorsed Richard’s work, prompting interest from publisher Houghton Mifflin. A year later, the publishing company formally issued Richard’s collection under the title New Orleans Cook Book—now regarded as the first Creole cookbook written by an African American.

The collection quickly became a bestseller. The recognition, says Young, came at a time when publishing companies privileged the culinary writing of white Southern authors—many of whom appropriated the recipes of African Americans, claiming them as their own. Richard’s clear writing and accessible recipes transcended the New Orleans food scene.

“Her seasonings were simple, yet impeccably balanced,” Young says. “It allowed the subtle flavors of the fresh seafood to sing out and harmonize with one another.”

Richard also gave credit where credit was due, acknowledging the cooks in her community who passed down the secrets behind their dishes; to name a few recipes: Baked Turtle in Shell, Stuffed Oysters, Gumbo Filé, Crawfish and Shrimp Bisque and Turtle Soup. Richard dedicated herself to writing down and recording generations of African American cooking traditions in New Orleans.

In the preface of Richard’s cookbook, the careful reader will note the chef’s resolve to further strengthen her community—“to teach men and women the art of food preparation and serving in order that they would become capable of preparing and serving food for any occasion and also that they might be in a position to demand higher wages,” she wrote.

In 1937, Richard had opened her cooking school, educating young African Americans with the culinary and hospitality skills needed for employment in the Jim Crow South and to push for a better financial position. The following year, she opened a frozen food company.

“She’s supporting the community in large part by opening doors to people,” says Paula Rhodes, Richard’s granddaughter. “The cooking school wasn’t just to make money, it was to pass forward what Mrs. Vairin had done for her and to provide accessible training in her area.”

After the release of her cookbook, Richard was persuaded to travel to Garrison, New York, to assume the role as head chef of the Bird and Bottle Inn. However, she returned to New Orleans and in 1941 opened her own New Orleans-style restaurant called Lena’s Eatery—“The Most Talked of Place in the South.” But she soon left north again to Colonial Williamsburg to take on the position of head chef at the Travis House, where she won over the respect from both food critics and local elites—after one of Mama Lena’s meals, Winston Churchill’s wife Clementine and their daughter Mary went back to her kitchen to exchange autographs.

Despite her success among the northern upper class, Mama Lena made her way back to New Orleans where, in 1949, she founded Lena Richard’s Gumbo House, transforming it into a welcoming community space for blacks and even a few whites, who dared to defy segregation laws. The restaurant sat on the border of one of the city’s African American neighborhoods and across from the Holy Ghost Catholic Church in Uptown New Orleans. Her daughter Marie Rhodes recalls how after the parish’s 11 a.m. mass, churchgoers arrived to chat, drink coffee and partake of the food Richard prepared for her Sunday menu.

By late 1949, her New Orleans fans were tuning into her TV show, witnessing the chef at work and learning from her expertise. The achievement, notes Young, comes at a time when television was becoming ever popular, yet many women of color were barred from showcasing their talent on media platforms.

Ruth Zatarain, a local resident and early fan of Richard’s television show, remembers taking out a pen and pencil in case she picked up new recipes and tips. “She cooked the kind of food that New Orleanians were used to eating. Not restaurant food, not all the fancy food,” Zatarain told Young. “And when she was talking to you, it was like you were talking to her in her kitchen.”

In 1950, Richard died unexpectedly. She was 58.

But what the New Orleanian chef left behind blazed a trail for both the expansion of Creole cuisine and for aspiring African American cookbook authors, including Freda DeKnight (A Date with a Dish) Mary Land (Louisiana Cookery) and Leah Chase (The Dooky Chase Cookbook)—hailed as the “Queen of Creole Cuisine” and inspiration behind Disney’s Princess and the Frog.

Mama Lena not only created a career out of a common employment for women of color, but she also used her experiences as a way for change in her African American community. “She [Richard] stepped out on the water when there was no guarantee it would hold her up," said Jessica B. Harris, a food historian and author of High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America.

“Lena Richard defied those damaging stereotypes of black working women at the time to show what so many people in New Orleans’ African American community already knew,” Young says. “That African American women are capable, smart, ambitious and facing so many barriers—but that those barriers could be overcome.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)