When the Smithsonian’s new Hall of Fossils—Deep Time exhibition opens its doors on June 8, hundreds of species will spring to simulated life. The 700 fossil specimens that roam the hall cover a lot of paleontological ground, spanning 3.7 billion years of our planet’s history and representing a wide variety of organisms, from furry mammals to tiny insects to leafy fronds. Among them are some of the most iconic and fearsome creatures to ever walk the Earth: the dinosaurs who dominated the ancient Mesozoic Era. These creatures are striking updated poses for the new display—some dramatic, some understated, but all up to date with current scientific research. Since the hall closed for renovations in 2014, experts have spent years carefully fiddling with the museum’s prehistoric skeletons, making sure every bone is in place to tell an engaging story and represent the newest discoveries in paleontology. Take a look at six of the toothy, spiky, scaly stars of the new hall—now ready for their closeup.

Tyrannosaurus rex

The dino: There’s a reason T. rex, which lived 68 to 66 million years ago, has grown into a fearsome cultural icon, stomping across movie screens and into the world’s imagination. The predator was one of the largest carnivores to ever walk the Earth, towering over other dinosaurs at more than 15 feet tall and 40 feet long. With its huge serrated teeth, shaped and sized like bananas, T. rex could tear through flesh and crush bone, eating up to hundreds of pounds of food in a single bite. The carnivore earned its name, which translates to “tyrant lizard king,” dominating its food chain by devouring plant-eating prey and even smaller carnivores.

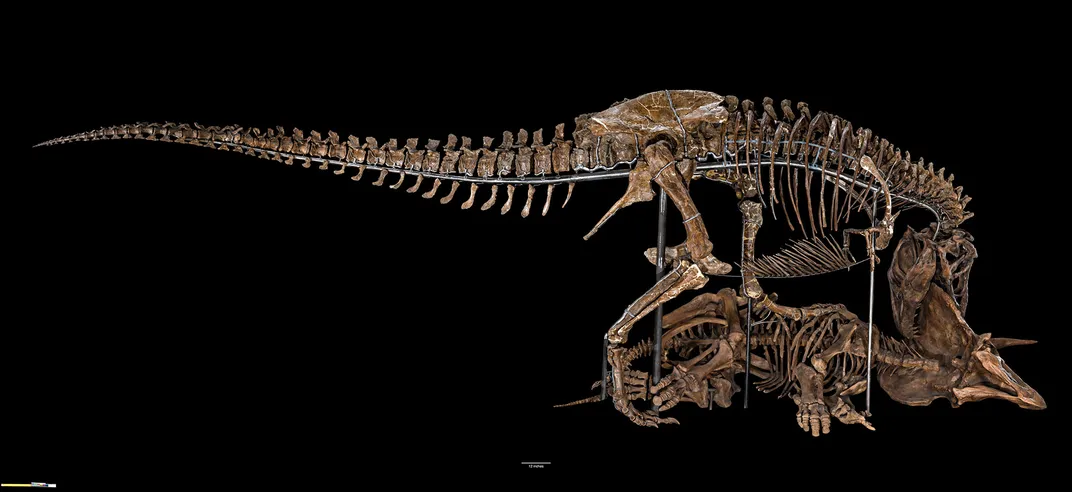

The fossil: The T. rex reigns supreme as the bold centerpiece in the new fossil hall. The creature is dramatically posed either about to deliver a death blow to its prey, the Triceratops, or taking a scrumptious bite of an already dead one. Dubbed “The Nation’s T. Rex,” the fossil is just beginning its stay in the capital as part of a 50-year loan from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Recreational fossil hunter Kathy Wankel discovered the specimen in Montana in 1988 while digging around on a family vacation. When a team from the nearby Museum of the Rockies completed the excavation, they found the T. rex was well intact, with about 50 percent of its bones in place.

Research and questions: Though the T. rex fossil is one of the best-studied specimens in the hall, it still has some secrets to reveal, says Matt Carrano, the museum’s dinosaur curator. Scientists still aren’t sure whether T. rex was a brutal killer or more of a scavenger, or some combination of the two. In the display, Carrano says curators intentionally left some room for interpretation as to whether the predator is killing a live Triceratops or chowing down on a carcass. And, of course, there’s the mystery of how T. rex used its tiny arms, which were too short to hold onto prey. It appears the arms were still functional, with all necessary muscles in place to offer mobility and some strength, but paleontologists, says Carrano, are stumped when it comes to their potential use.

Triceratops

The dino: Despite its massive size—roughly the same as an elephant’s—and intimidating horns, Triceratops, which lived 68 to 66 million years ago, was a (mostly) peaceful herbivore that munched on shrubs and palms. The dinosaur may have used its horns and bony neck frill to protect itself from predators like a hungry T. rex or to battle for a mate. Triceratops had a huge head, about one-third the length of its whole body, and its beak-like mouth was filled to the brim with up to 800 teeth.

The fossil: The Deep Time Triceratops is actually a “computer-assisted digital version” of the museum’s former display specimen, Carrano says. The original skeleton was a composite that borrowed bones from ten different animals, which resulted in a charming but oddly proportioned mashup. After spending nearly a century on the museum floor in less-than-ideal display conditions, the fossil was in rough shape. So, in 1998, curators opted to replace the crowd favorite with a cast, created by scanning the original fossil and manipulating a digital version into a more accurate skeleton. The cast version, nicknamed Hatcher after the scientist, John Bell Hatcher, who collected the original skeletons in the late 19th century, is the one being attacked by the T. rex in the new hall. The original fossil is now held safely in the museum’s collections for research.

Research/questions: Paleontologists are pretty confident the Triceratops served as prey for T. rex. A number of studied Triceratops fossils are peppered with puncture marks from the lizard king’s distinctive teeth, Carrano says. Less certain is how Triceratops interacted among its own kind. Most Triceratops fossils unearthed by paleontologists lay in isolation, far from any others. In 2009, however, new research suggested the dinosaurs may have been more social than previously thought, after scientists discovered a “bonebed” with three juvenile Triceratops skeletons clustered together.

Camarasaurus

The dino: Camarasaurus lentus, which lived 157 to 148 million years ago, belonged to a class of gentle giants called sauropods. With its long, flexible neck and spoon-shaped teeth, the herbivore had its pick of leafy snacks, from high-up treetops to shrubby ground vegetation. Though scientists early on believed that Camarasaurus was a swamp dweller, a century-old study found the dinosaur, along with its fellow sauropods, actually walked tall on solid ground. Some scientists suggest Camarasaurus may have swallowed rocks to help it digest its leafy meals more easily—a fairly common practice among dinosaurs and their bird descendants—but there’s no direct fossil evidence of this practice in sauropods, Carrano says.

The fossil: In the old fossil hall, this Camarasaurus was curled up on the ground in what’s known as a death pose. Though that mount concealed some of the damaged portions of the delicate fossil material, it also made the specimen easy to overlook, Carrano says. Now, the herbivore is displayed in a more dramatic pose, rearing up over the hall. To achieve that new look, the fossil team dug out additional bones from the surrounding rock and prepared portions that were hidden in the previous setup. The Deep Time specimen is now a standout fossil display. It is likely the only sauropod mounted on its hind legs and using real fossils, Carrano says. The dinosaur’s head is the one piece of the display that is a cast and not a real fossil; the actual Camarasaurus skull is separately located on a platform beside the body, so visitors can get a closer look.

Research/questions: The specimen’s new pose may prove to be controversial, as some paleontologists don’t believe the Camarasaurus could rear on its hind legs, Carrano says—although he wonders how else they could have reproduced. While this specimen is quite complete relative to others of its kind, it has yet to be thoroughly studied. The museum’s well-preserved Camarasaurus skull could offer a way to better understand the internal anatomy of the dinosaur’s head, Carrano says, especially with the possibility of sending it through a CT scanner.

Allosaurus

The dino: Though not as notorious as T. rex, the Allosaurus was a similarly vicious theropod—or two-legged carnivore—that rivaled its infamous cousin in size. Allosaurus fragilis, which lived 157 to 148 million years ago, fed mainly on large herbivores, and may have tangled with the spiky-tailed Stegosaurus. Its unusual, hourglass-shaped vertebrae earned Allosaurus its name, which translates to “different lizard.” Some paleontologists think Allosaurus, which could reach speeds of more than 20 miles per hour, fed by running up to take a big bite out of its prey and then sprinted away before its victim had time to react.

The fossil: This specimen, excavated from the fossil-rich Morrison Formation in Colorado in the late 19th century, was one of the first mostly complete examples of the Allosaurus to be unearthed. Though the Allosaurus is relatively common as far as fossils go, paleontologists often find specimens in clusters with their bones all jumbled together, Carrano says. So, the fact that the museum’s skeleton came from one individual makes it unusual and has garnered a lot of scientific interest over the years. Because the Allosaurus was a predator, it’s often portrayed on the hunt, but curators opted to show a softer side of the animal for the new hall, Carrano says: The updated display shows Allosaurus tending to its nest, with its tail curled around a cluster of fossil eggs.

Research/questions: Despite the dinosaur’s domestic pose, researchers aren’t yet sure whether this particular Allosaurus was a female, Carrano says. This is one of a number of mysteries about the specimen Carrano and other researchers are actively working to solve; he says Allosaurus is number one on their list of research priorities, in part because the last thorough study of the fossil was completed almost a century ago (and also because it’s one of Carrano’s personal favorites). Using today’s updated technology and a greater base of dinosaur knowledge, researchers hope to answer questions of the dinosaur’s age and closely related species, as well as figure out the cause of a strange injury in the skeleton—a “wacky-looking” disruption where a whole new bone seems to have started growing out of a broken shoulder blade on the animal’s left side.

Diplodocus

The dino: Just like Camarasaurus, Diplodocus hallorum was a towering, plant-eating sauropod that live 157 to 150 million years ago. However, it had a stiffer neck than Camarasaurus, with longer vertebrae preventing it from bending too far up or down. Instead, Diplodocus used its neck more like a fishing rod, sticking its head straight out to mow down plants with its set of peg-like teeth (which may have regrown as often as once a month). It was one of the longest dinosaurs, with a body that could stretch to about 100 feet; most of that length came from its neck and tail. Some scientists believe Diplodocus could even crack the tip of its tail like a whip to communicate or scare off predators.

The fossil: This specimen is about 60 percent complete, Carrano says, with the body and back end mainly intact. The museum first put Diplodocus on display in 1931, after years of prep work to mount the enormous specimen. Now, after still more years of effort, the skeleton will once again tower over the Deep Time hall, this time in a more lively pose. Diplodocus now appears to be in lumbering motion, with its tail lifted slightly off the ground and its neck craning over visitors in the hall’s central walkway.

Research/questions: Researchers are working to uncover the cause of an unusual pathology in this specimen, Carrano says. The Diplodocus appears to have suffered some sort of injury or infection: In one big stretch of the tail, the dinosaur’s bones essentially fused together and turned the whole section rigid, with bone covering up joints and some tendons appearing to ossify. For the most part, though, Diplodocus is a fairly well-studied and well-understood dinosaur, Carrano says.

Stegosaurus

The dino: Though Stegosaurus stenops itself was an herbivore, the distinctive dinosaur was strategically adapted to fend off would-be predators. Its skin was covered with a built-in armor, including bony nodules guarding its neck and jagged plates down its back. Spikes covering the tip of its tail transformed the creature’s flexible back end into a mace-like weapon. The Stegosaurus, which lived 157 to 148 million years ago, probably fed on plants low to the ground, since it had a short neck not well-suited for reaching toward treetops. It also boasts one of the smallest brain-to-body size ratios of any dinosaur. Scientists have described the Stegosaurus’ brain as about the size and shape of a bent hot dog, compared to its enormous schoolbus-sized body.

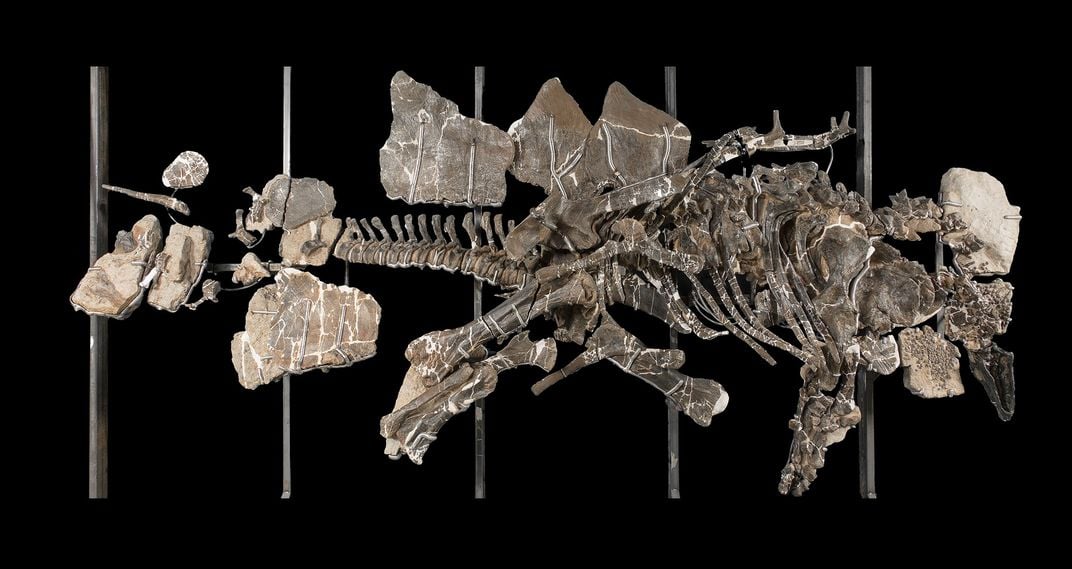

The fossil: This Stegosaurus, on display at the far end of the hall nearest the FossiLab, is a very special individual: It’s actually the type specimen for its species, the first of its kind to be discovered and named. Before this fossil was excavated in 1886, paleontologists only had bits and pieces of Stegosaurus skeletons, with no clear idea of what a complete one would look like. Since then, this signature fossil has served as the reference specimen for the species; meaning that whenever a scientist thinks they might have a S. stenops fossil on their hands, this is the model they use for comparison. The Stegosaurus is mounted exactly how it was originally found in Colorado, in the death pose it was holding in its rocky tomb, Carrano says. However, curators chose to display it vertically—not semi-buried on the floor, as it was in the old fossil hall—so visitors can get a fuller view of the specimen.

Research/questions: The Stegosaurus has an anatomy that is simply “weird,” Carrano says. For one, the bones of its backbone are especially tall, which makes the back extra stiff, and paleontologists are still stumped as to why. Its front legs are shorter than its back ones, which doesn’t make a lot of sense for a dinosaur that seemed to walk on all fours. Even the purpose of the bony plates lining its back remains a bit of a mystery. “There’s a lot about their anatomy that, while we know what it looks like,” says Carrano, we don’t know how it works.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/5b/da5bbdba-72c8-42ef-bbbc-470030288020/nmnh-2019-00497.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)