A Mexican Painter Changed by the City, Changes Art

“In New York, I went berserk over painting,” said Rufino Tamayo, whose works are now on view in a new retrospective

It’s not only the people one meets in a big city that can be inspirational. For artists, it’s often the work they see there.

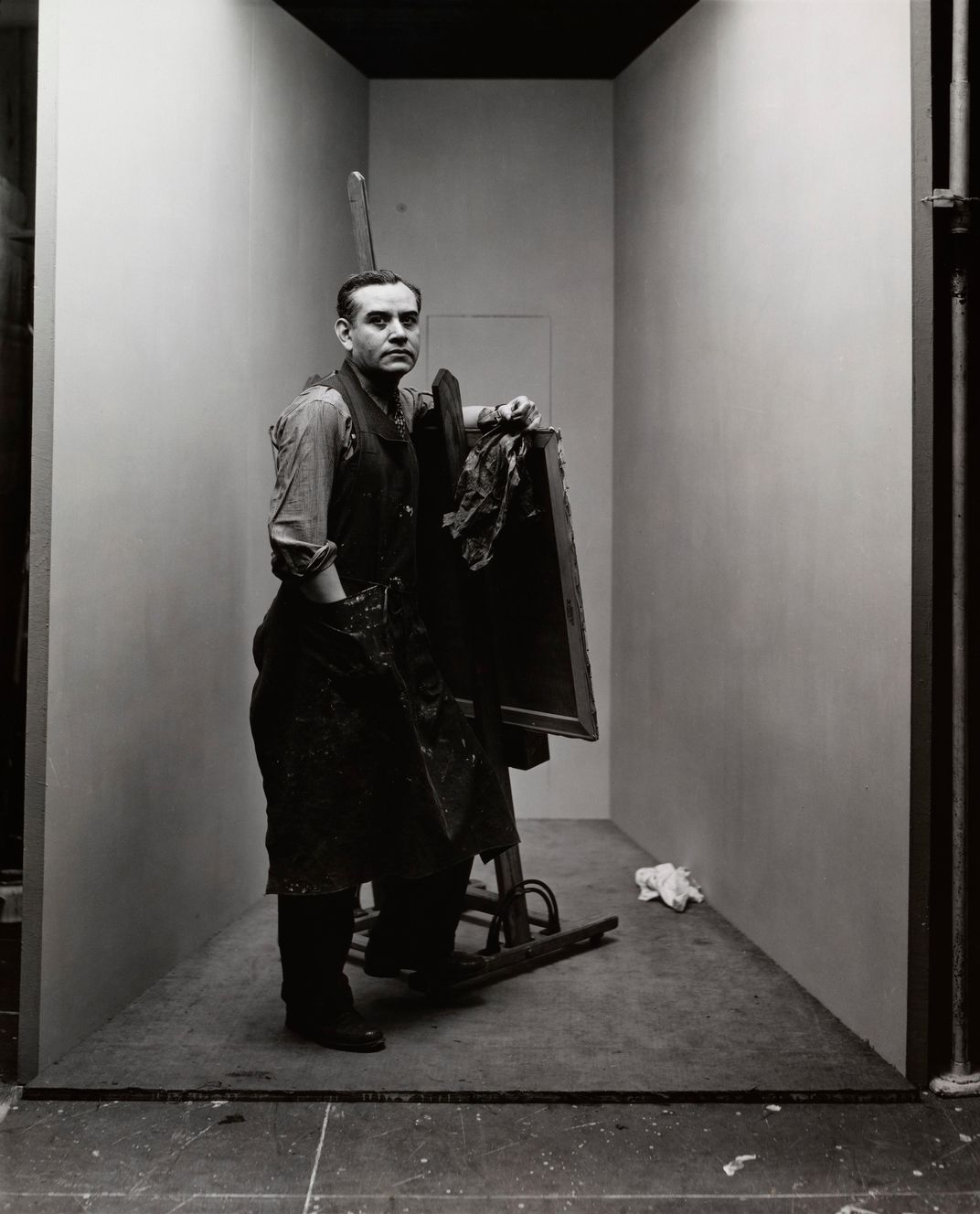

The Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo got acquainted with a number of artists the first time he moved to New York City in the 1920s, among them Reginald Marsh and Stuart Davis.

But the greatest impact of that city on his painting was chiefly visual, from the skyscrapers outside his terrace, to the swirl of amusements at Coney Island to the exciting gallery work in the international art capital that struck him like thunder. A colorful new exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum traces the connections between New York’s cultural dynamics and what Tamayo put on canvas in the first half of the 20th century. Forty-one works from 1925 to 1949 comprise Tamayo: The New York Years, the first major retrospective of the artist in a decade, and the first to concentrate on his crucial New York years.

In the early 20th century, New York City was becoming the place for artists to be, says E. Carmen Ramos, the museum’s curator of Latino art, who spent three years creating the show. “There," she says, “Tamayo saw works by major European modernists for the first time.” Face to face with the work, Tamayo would later say.

“In New York, I went berserk over painting. There, I experienced the same passion that I had felt during my encounter with popular and pre-Hispanic art,” he said.

Those influences had informed his work and served him well; it was the native influence, too, that was motivating contemporaries from Jackson Pollack to Marc Rothko. But suddenly Tamayo was face to face with Europeans that included Matisse, Braque and Duchamp.

“One of the artists he was taken with was, surprisingly to me, Giorgio de Chirico,” Ramos says. He was really interested in how De Chirico mixed all of these different temporalities, in part because the cultural scene in Mexico was also interested in merging the past and present, given the strong interest in indigenous culture as well as the modern era.”

It was difficult for Tamayo to find a footing in New York; he only stayed two years in the 1920s, returning in the early 1930s just as the Depression was having its effect, making staying difficult. He returned for the longest period from 1936 to 1949. All told, he lived in the city 15 years before he left for Paris in the postwar period.

During that time, he became more enamored with the city, as seen in his attraction to the swirls and sounds of Coney Island in the 1932 Carnival, a recent acquisition to the museum; and in the colorful 1937 cityscape, New York Seen from the Terrace, a kind of self-portrait, as it depicted the artist and his wife surveying the spires all around them.

Most influential to him that decade may have been a Pablo Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1939, which coincided with the unveiling of Picasso’s masterpiece Guernica at the very gallery where Tamayo was also showing.

“These two events had seismic implications not just for Tamayo, but for many artists in New York,” Ramos says.

Tamayo was inspired to depict the scenes of Mexican folk art he had been doing using masks, in the way that African masks had influenced Picasso. But Guernica in particular struck Tamayo to the core, Ramos says. “It really signaled a different approach to engage with the crises of the day.”

Picasso’s masterpiece was seen “not only as an antiwar painting, but as an aesthetic antiwar painting. And Tamayo really drew inspiration from that example.”

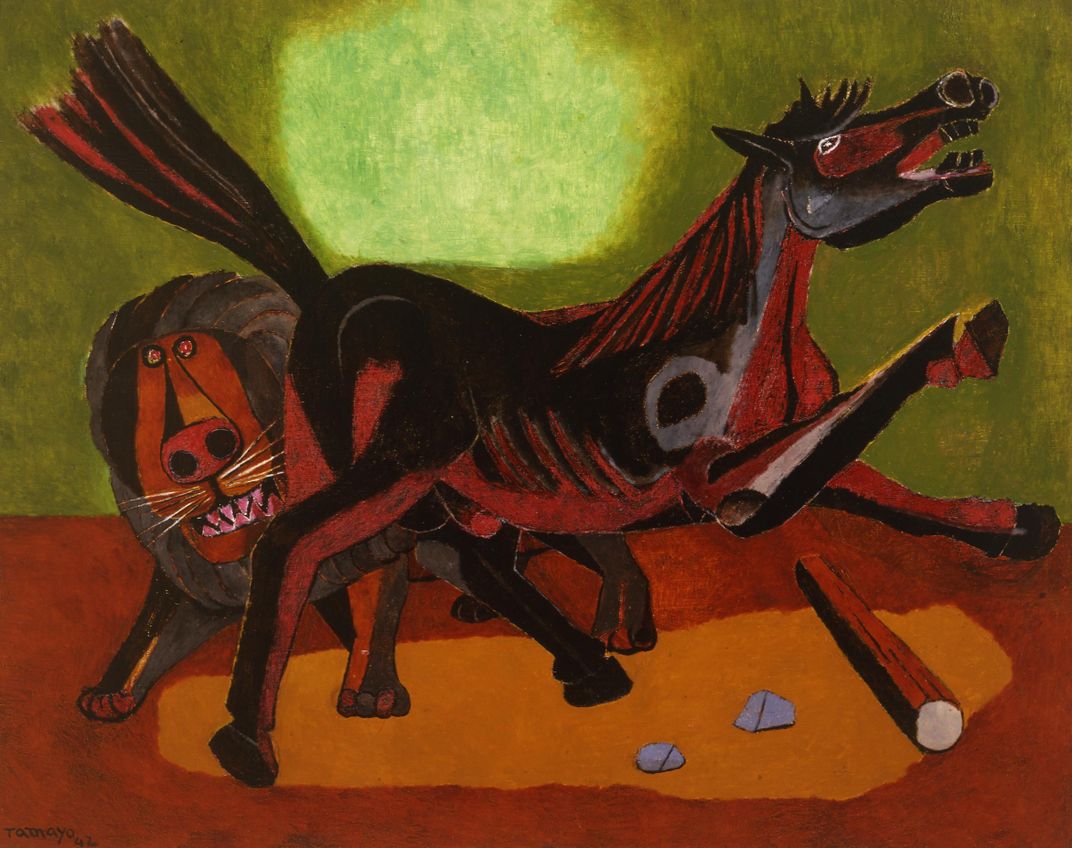

It’s clearly seen in a series of paintings Tamayo did between 1941 and 1943, using animals as an allegory for exploring the anxiety surrounding World War II. The twisted face of his howling dogs in Animals, as well the creatures in Lion and Horse, mirror the same agonized expression as the horse in Picasso’s painting.

Tamayo: The New York Years

Mexican American artist Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991) is best known for his boldy-colored, semi-abstract paintings. This is the first volume to focus on Tamayo's work during his time in New York City, where he lived from the late 1920s to 1949, at a time of unparalleled transatlantic cross-cultural exchange.

One sure sign of his success, Ramos says, is that his works of this period “were acquired almost immediately after they were created.” Animals, painted in 1941, was already in the Museum of Modern Art collection by 1942.

“Tamayo is hailed again during this period for redirecting Mexican art and for creating work that responded to the moment in which we’re living, and art that was based on the culture of the Americas,” Ramos says. He extended the allegory in a 1947 work that gets prominent placement at the Smithsonian exhibition, Girl Attacked by a Strange Bird.

“He wanted to explore this anxious moment in global history, this post-war moment, but he didn’t want to do it in narrative terms,” Ramos says. “He really turned to allegory.”

In doing so, he also returned to subjects he had long been using, she says. “He blended his interested in Mesoamerican art and Mexican popular art with this idea of engaging the modern crises of the day, in allegorical terms.”

The attacking bird certainly conveys this postwar anxiety, if not the off-kilter tilt of the girl.

Throughout his career, Tamayo’s paintings never abandoned the representational—which may explain why his star fell a bit amid New York art circles embracing abstraction to the exclusion of anything else.

Tamayo stayed with figures, Ramos says, because it remained important for him to continue to communicate with an audience. He painted his last work in 1990, a year before his death at 91 the following year. Like his fellow Mexican artists, Tamayo worked in murals—an influence that rose north to America and helped inspire the Federal Art Project of the Workers Progress Administration during the New Deal.

But unlike colleagues like Diego Rivera, Tamayo was not interested in using his art for overtly political reasons.

Instead, he was interested in concentrating on form and color, Ramos says, and in adopting the color of Mexican ceramics and of popular Mexican folk art.

In his influential time in the city, Ramos concludes her essay in the accompanying catalog, “Tamayo absorbed the New York artistic scene, was transformed by it, and also helped redefine notions of the national across the Americas at a crucial time in history.”

“Tamayo: The New York Years” continues through March 18, 2018 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)