The finalists for the title of Miss America 1948 were bustling around backstage in the suspenseful closing moments of the annual pageant when a motherly volunteer issued the command: “Girls, get into your swimsuits.” Yet as they raced off to change, she stopped BeBe Shopp from following the others.

“I thought I’d done something wrong,” recalls Shopp, who was an 18-year-old farmgirl and vibraphone player when she arrived in Atlantic City, New Jersey, as Miss Minnesota.

Suddenly, the pageant’s formidable executive director Lenora Slaughter appeared at Shopp’s side. From her handbag, she unspooled the coveted lettered sash: “Miss America 1948.” And that’s how Shopp learned she had won.

Shopp’s four runners-up—including Miss Kansas Vera Miles, the future star of the classic 1960 horror film Psycho—would take the stage that September night to claim their prizes in the swimsuits they had worn into the competition: black-and-white striped Catalina maillots. The crowning of the Miss America court traditionally played out this way, the top five in the skimpy beachwear that had defined the pageant from its beginnings. But Slaughter had a new vision for 1948: Miss America herself would be crowned, not in her swim togs, but in a full-length evening gown.

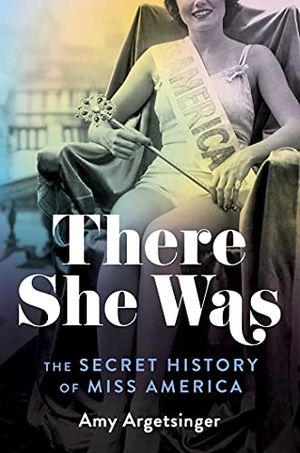

There She Was: The Secret History of Miss America

For two years, Washington Post reporter and editor Amy Argetsinger visited pageants and interviewed former winners and contestants to unveil the hidden world of this iconic institution. There She Was spotlights how the pageant survived decades of social and cultural change, collided with a women’s liberation movement that sought to abolish it, and redefined itself alongside evolving ideas about feminism.

“She wanted an image,” explains Shopp. Slaughter was always searching in those days for ways to dignify the title and elevate the women who won it.

Last month, the 91-year-old Shopp donated her original Catalina swimsuit to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History—one of the first big acquisitions in a new initiative to collect items connected to the Miss America pageant on the occasion of its 100th anniversary.

Ryan Lintelman, the museum’s curator of entertainment, says the pageant’s ever-shifting attempts to define some notion of ideal womanhood make it a fascinating lens to examine a century of American social and cultural change. Some items may find a home in the long-term “Entertainment Nation” exhibition scheduled to open in 2022.

Other acquisitions include a hearing-aid-compatible microphone used by Heather Whitestone, the first deaf Miss America of 1995; the insulin pump worn during the 1999 competition worn by Miss America Nicole Johnson, who advocated for diabetes awareness during her reign; and the mandarin collar pantsuit that Miss America 2001 Angela Perez Baraquio, the first Asian-American winner, appeared in for her on-stage interview as a tribute to her Chinese lineage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fa/47/fa47c540-6387-42fa-8ae8-5835b5140e47/gettyimages-1229543253.jpg)

These objects chart Miss America’s fitful evolution into the modern era—from a giddy seaside beauty contest to the multi-layered competition a generation grew up watching on TV, through decades when organizers strived to celebrate merit, professional ambition and cultural diversity. In 2018, to diminish the emphasis on physical appearance, pageant organizers scrapped the swimsuit competition.

And yet as I learned while researching my new book, There She Was: The Secret History of Miss America, no single artifact—not a rhinestone crown or a sash or a scepter—better epitomizes Miss America’s complicated history than a swimsuit. Despite efforts to place the iconic look firmly in the review mirror, Shopp’s Catalina maillot proves a revelatory artifact and one that tells much of the pageant’s story.

"That swimsuit really is the crux of our collecting initiative and the most important piece so far," says Lintelman. "It's a link to the past that represents the tensions that we're interested in from the history of the pageant."

Miss America was hardly the first beauty competition. But it immediately became a sensation upon its debut in September 1921, thanks to the unique dress code. The pageant was part of Atlantic City’s “Fall Frolic,” an attempt to hook tourists for a stay beyond Labor Day. Every reveler in attendance wore swimwear—not just the young ladies competing in a little sideshow that was originally called the “Inter-City Beauty Contest.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/0e/6b0e018d-eee4-431a-9be7-7aa80173c8bc/gettyimages-3202847.jpg)

Only a few years earlier, women had been wading into the surf in the equivalent of baggy dresses, while men wore pants and shirts. But by the 1920s, new mechanized knitting techniques allowed for a more athletic, streamlined costume that revealed the wearer’s natural silhouette. It was a highly liberating look for many women—maybe too liberating in the eyes of contest judges. That first year, they selected as their winner 16-year-old Margaret Gorman of Washington, D.C., the youngest girl in the lineup. She was the furthest from a vivacious flapper, heralded for her unbobbed curls and the demure skirted swimsuit she wore of tiered chiffon. But over the long haul, slinky styles would prevail.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1c/4d/1c4d8a63-47a3-490b-95fc-a2be233c4f3a/collection_i_86_9.jpg)

In 1935, the pageant was roiled by its first scandal when it was reported that winner Henrietta Leaver had posed nude for a Pittsburgh artist’s sculpture. Leaver indignantly maintained that she had worn a swimsuit during the modeling session—an entirely plausible explanation at a time when the clingy knits left little to the imagination.

The pageant quickly became a national happening, news photographers lured back year after year chronicled the scantily clad young women parading up and down the iconic Convention Hall runway. After BeBe Shopp’s victory, front-page news stories across the country wolfishly assessed her “buxom” figure and publicized her bust-waist-hips measurements. Swimwear had become big business, and the Catalina company attached itself to the pageant as a major underwriter.

To this day, though, Shopp has questions about the sponsor’s choice of those striped suits. “We looked like a bunch of zebras on stage,” she says. (Or, as one journalist snarked at the time, a pack of San Quentin inmates.)

“It has no support in the bust at all. And we weren’t allowed to put padding in it.” In an era before French-cut tailoring, the contestants tried to stretch the horizontal leg holes higher up the hip for a lengthening effect. Catalina boasted that the swimsuits kept their shape thanks to Lastex, an innovative new rubber-elastic thread, but the fabric it undergirded was a cable-knit wool, Shopp notes.

“I can’t imagine anyone going into the water in this thing,” she laughs.

Lenora Slaughter’s decision to have the new Miss America receive her crown in an evening gown instead of a swimsuit spoke to a perpetual tension within the pageant.

Conservative hoteliers in Atlantic City had shut the pageant down for a couple years in the late 1920s, scandalized by spotlight-seeking young women clad in their sexy bathing clothes. Hired to resuscitate it, Slaughter attempted to class up its image with talent competitions, college scholarships, chaperones and strict codes of conduct. (She also imposed racist entry requirements, specifically excluding Black women for many years.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/50/df/50df7d1d-35b9-4f62-9eaa-92ab7fa1e872/nmah-ac0888-0000001.jpeg)

Yet those swimsuits remained central to the whole operation. Shopp accepted the gawking as a given—she was 18 years old, and thrilled to have clinched a scholarship that would put her through music school. Gamely she went on a national tour for Catalina during her Miss America reign, modeling swimsuits in department-store fashion shows.

Just two years later, though, another Miss America rebelled. Yolande Betbeze, a soprano from Alabama, declared after her crowning that she was done with posing in swimwear. She wanted the world to focus on her singing instead.

Outraged Catalina executives pulled their funding—and launched rival pageants, which would become known as Miss USA and Miss Universe. (These were the pageants, free from any pesky talent requirements, that decades later would be co-owned for several years by former President Donald Trump.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/80/01805780-9bac-487c-a9e3-53c640e905c3/nmah-2006-7451.jpeg)

In 1968, after feminists staged a sensational protest blasting Miss America as a tool of the patriarchy, internal handwringing erupted over whether the swimsuit competition put the pageant out of step with the times: Miss America chairman Al Marks predicted it would be gone within three years. Contestants “find it uncomfortable to walk 140 feet of runway in a bathing suit under 450,000 watts of light,” he said in 1970. “This is just not a natural surrounding for a bathing suit.”

But the swimsuit competition persisted, serving as something of a bellwether of the social changes that would arrive with younger generations.

As outspoken and ambitious baby boomers entered the pageant, they brought a more professional mindset to pageantry. By the early 1980s, the fiercest competitors armored themselves in custom-fitted swimsuits with lift-and-separate engineering and a girdle-like fabric (not suitable for swimming). These so-called “supersuits” seemed unbeatable—until they became ubiquitous, an effect that pageant CEO Leonard Horn compared to a cadre of “Stepford Wives.”

“They didn’t look real,” he told me in an interview for my book. “And they weren’t comfortable in their façade.”

Horn banned custom-made swimwear in the 1990s, in a bid to reclaim a more youthful, less fussy aesthetic, and lifted the pageant’s prohibition on bikinis. But the baring of midriffs may have ratcheted up the pressure for contestants—many of them early adopters of fitness culture. Spray-tanned, polished-marble abs became the new standard, along with supermodel strides and hair-flipping moves that would have been at home in a Victoria’s Secret fashion show. (Lintelman has also acquired swimsuits representative of this era: Whitestone's early-90s one-piece, designed strictly for pageant use, and Johnson's late 90's high-waisted bikini.)

And then suddenly, Miss America pulled the plug on swimsuits. The move came in the wake of the MeToo movement of late 2017; the catalyst was the pageant’s leader at the time, Gretchen Carlson, the former Fox News host who had won a massive sexual harassment settlement from network co-founder Roger Ailes and had served as Miss America 1989. The intent was to rebrand Miss America for a new generation and signal an open-door welcome to all young women of merit, exclusive of their looks.

But the move came at a time of waning interest in the Miss America contest; and it has done little to jolt a hoped-for influx of new contestants, sponsors and viewers. Once one of the most-watched shows of the year, the pageant drew fewer than 4 million viewers in 2019 and this year will be aired on the low-rated Peacock streaming service instead of broadcast television. In the 1970s and ’80s as many as 80,000 young women competed in the local pageants that sent its winners to Miss America; these days, only a couple thousand enter the chase for a crown.

Some contestants admit they miss the swimsuit competition. “I have never been more confident and strong,” Miss America 2017 Savvy Shields told me. In training for the competition, “I learned to love my body not for the way it looked but the way it worked.”

BeBe Shopp, though, was glad to see it go. “We’ve got to change to keep up with the women of this country,” she says, and she has little patience for the those who yearn to restore it. With one exception. “If they would go back to the one-piece,” she says, “I might agree.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9a/6a/9a6abd15-34ca-4fb9-9c72-5c8a47667d99/untitled-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/001__argetsingercrop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/001__argetsingercrop.jpg)