A Mural on View in the African American History Museum Recalls the Rise of Resurrection City

The 1968 Hunger Wall is a stark reminder of the days when the country’s impoverished built a shantytown on the National Mall

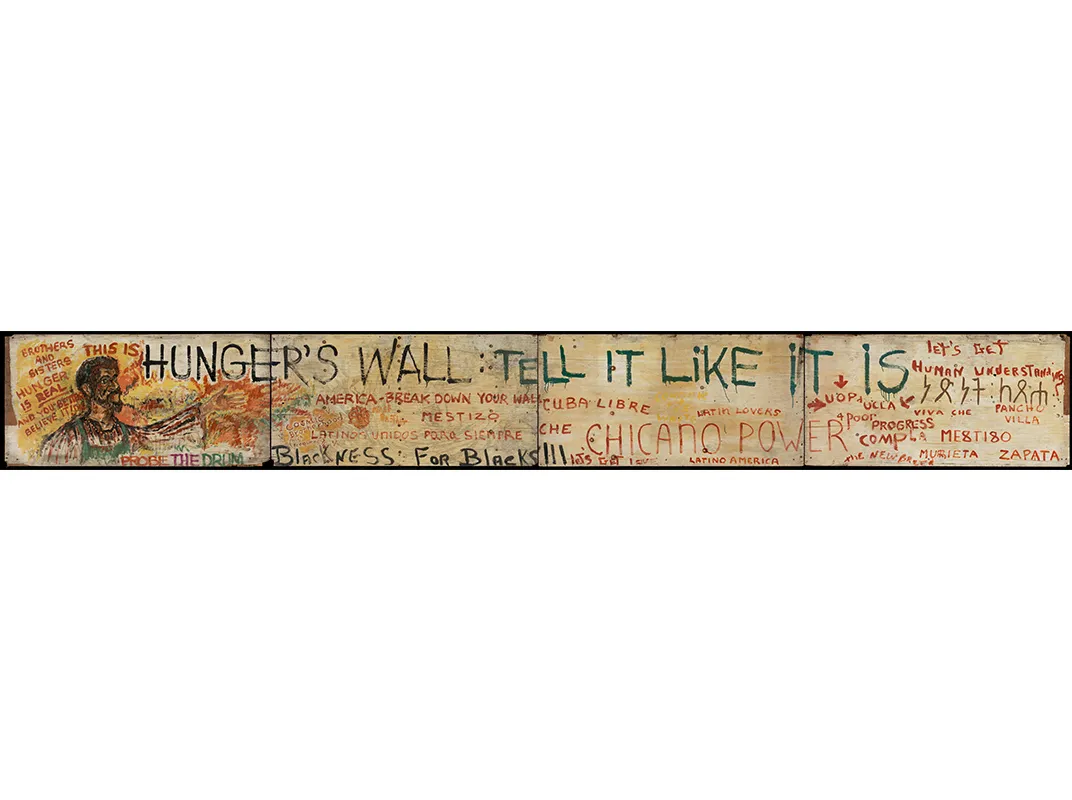

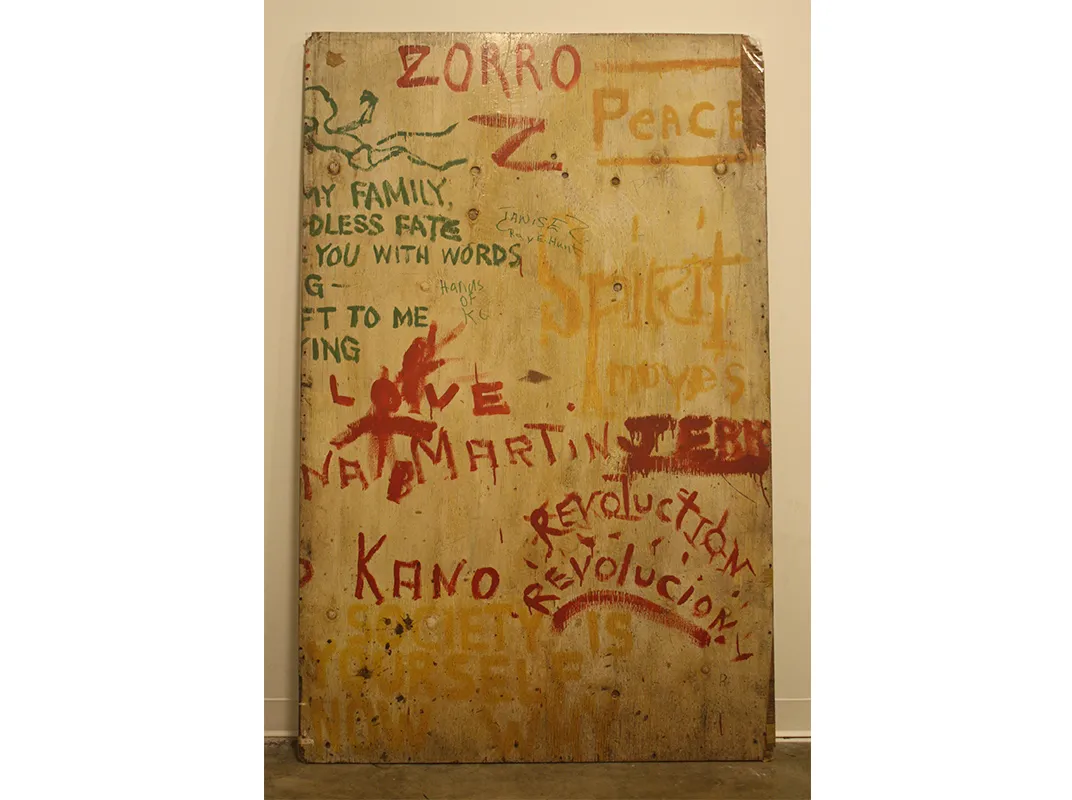

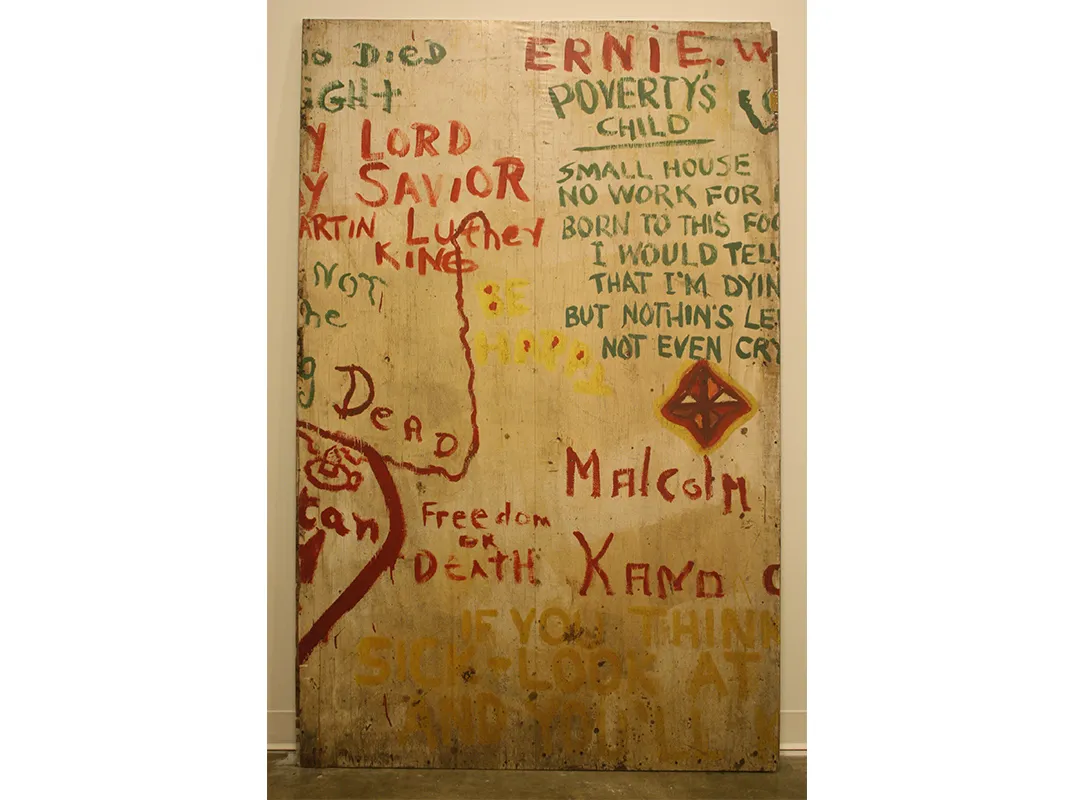

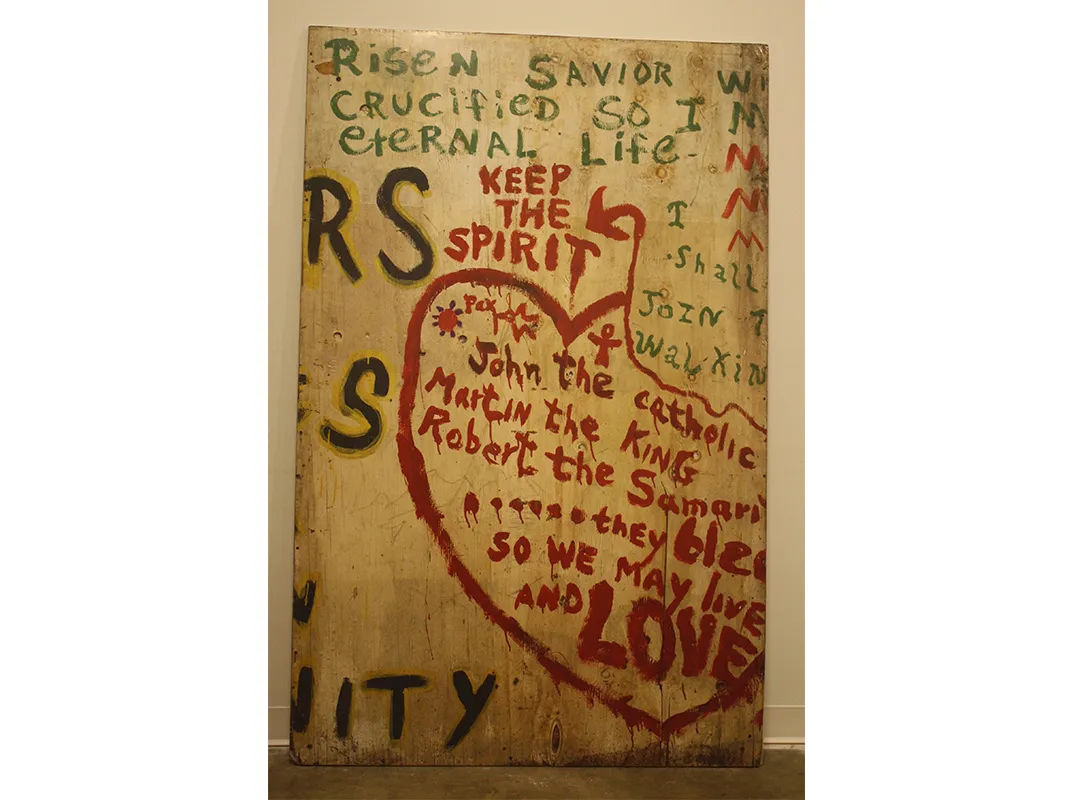

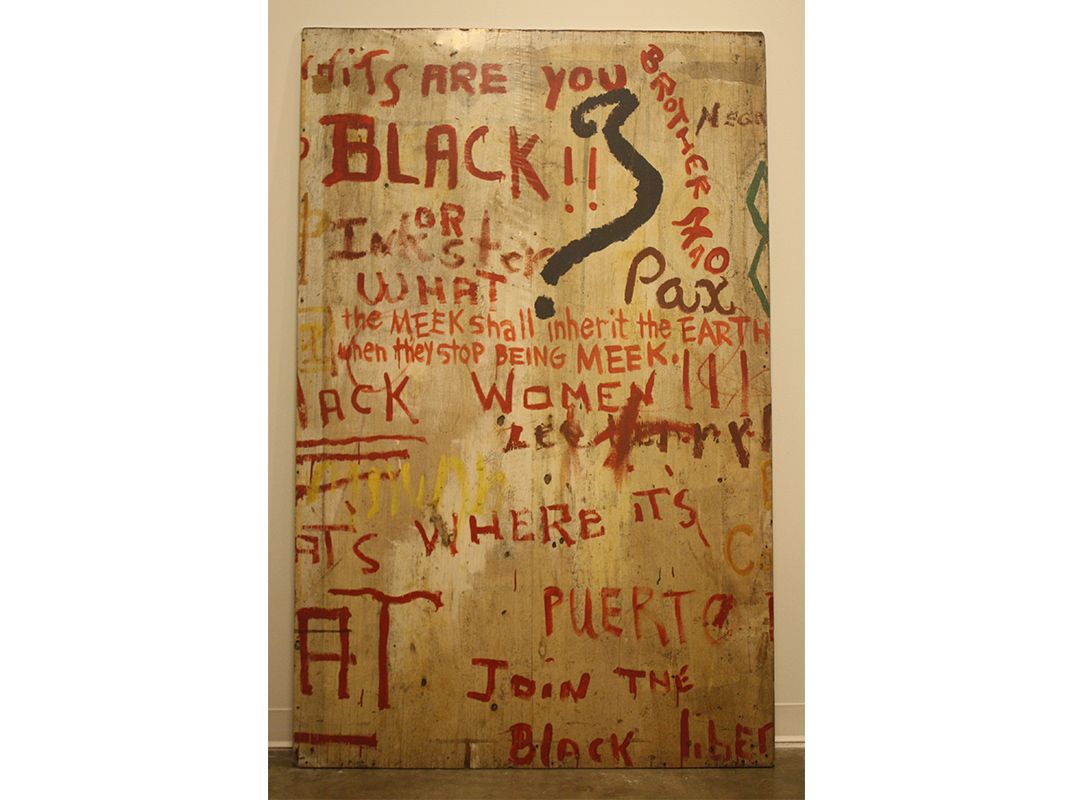

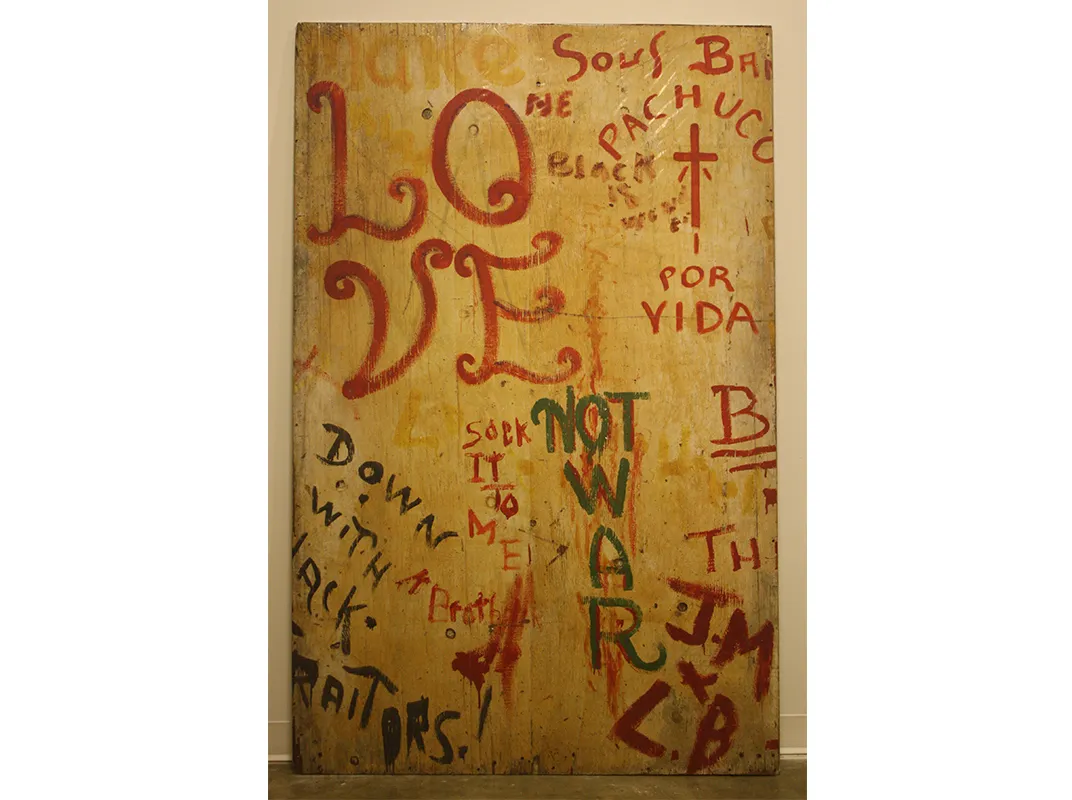

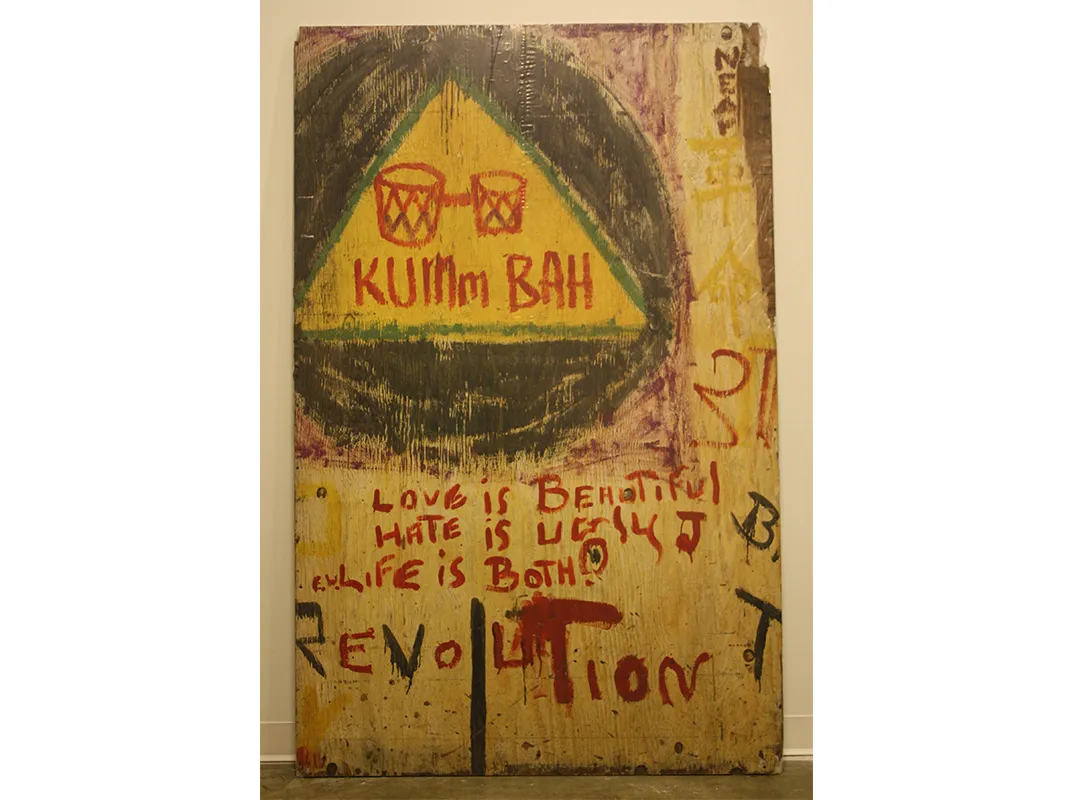

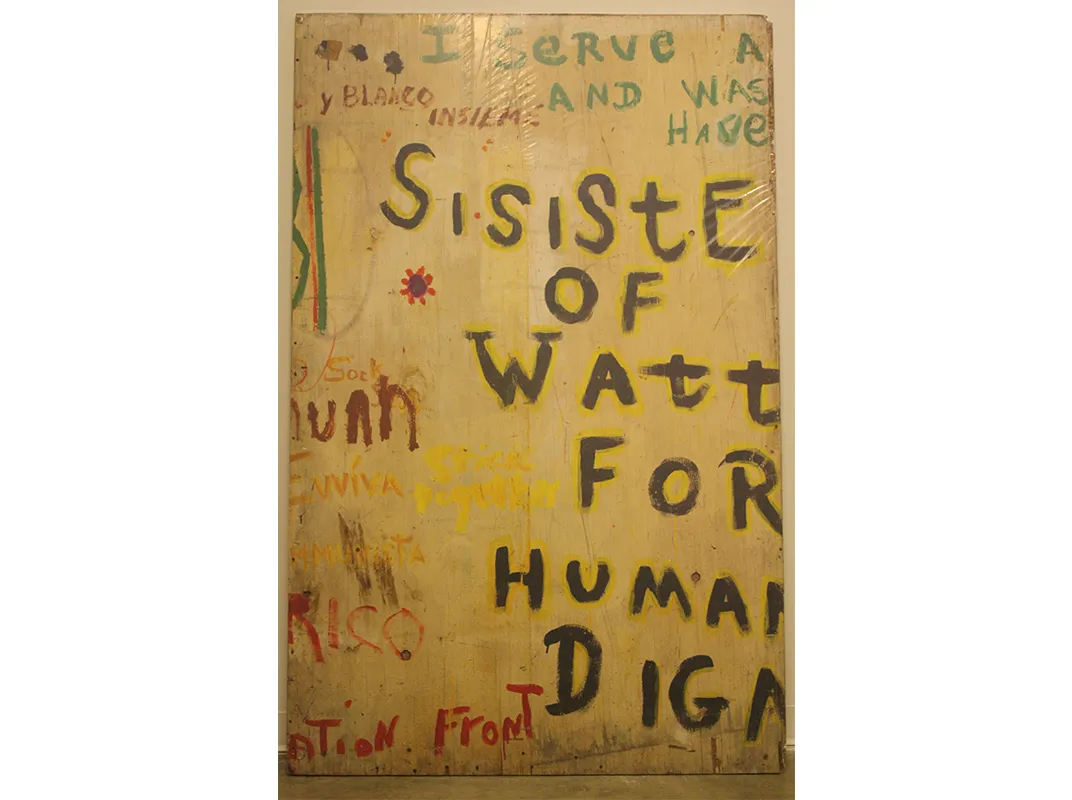

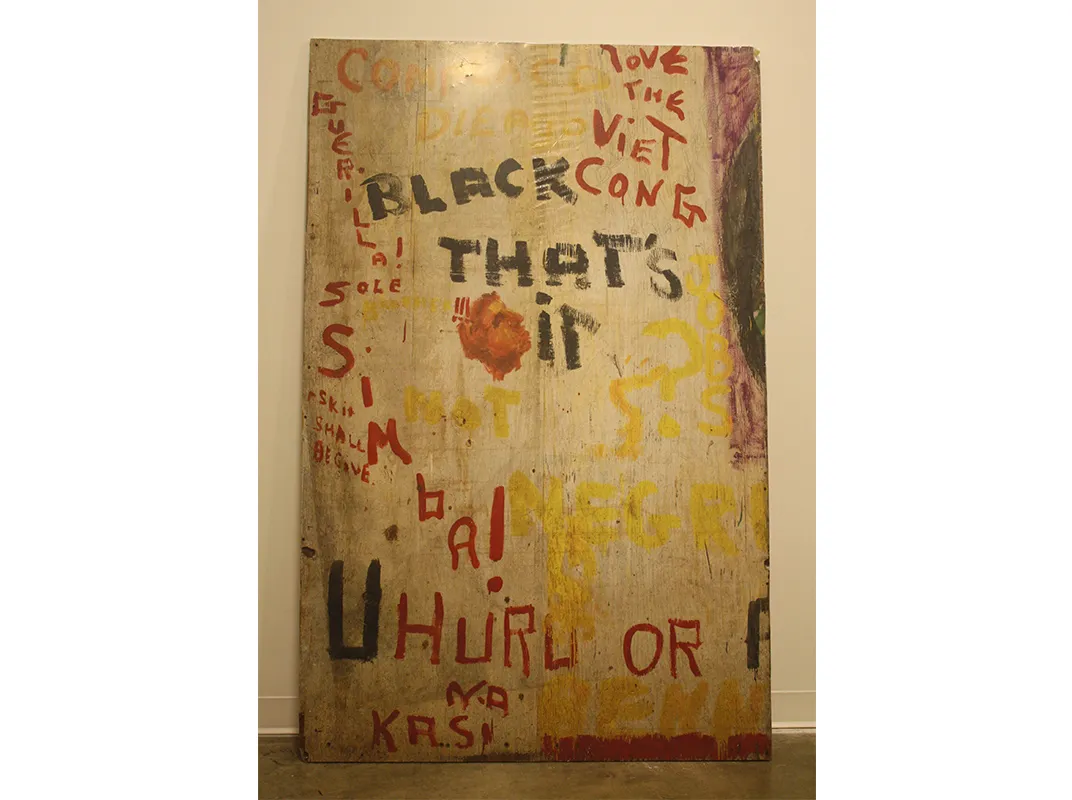

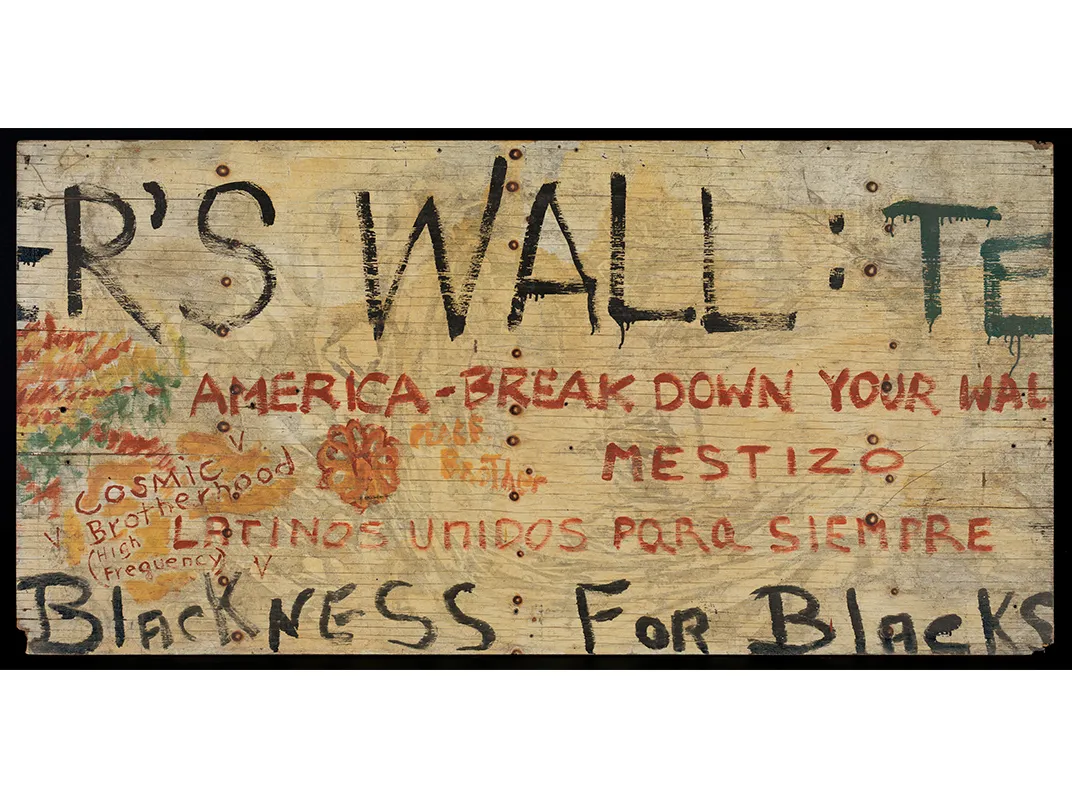

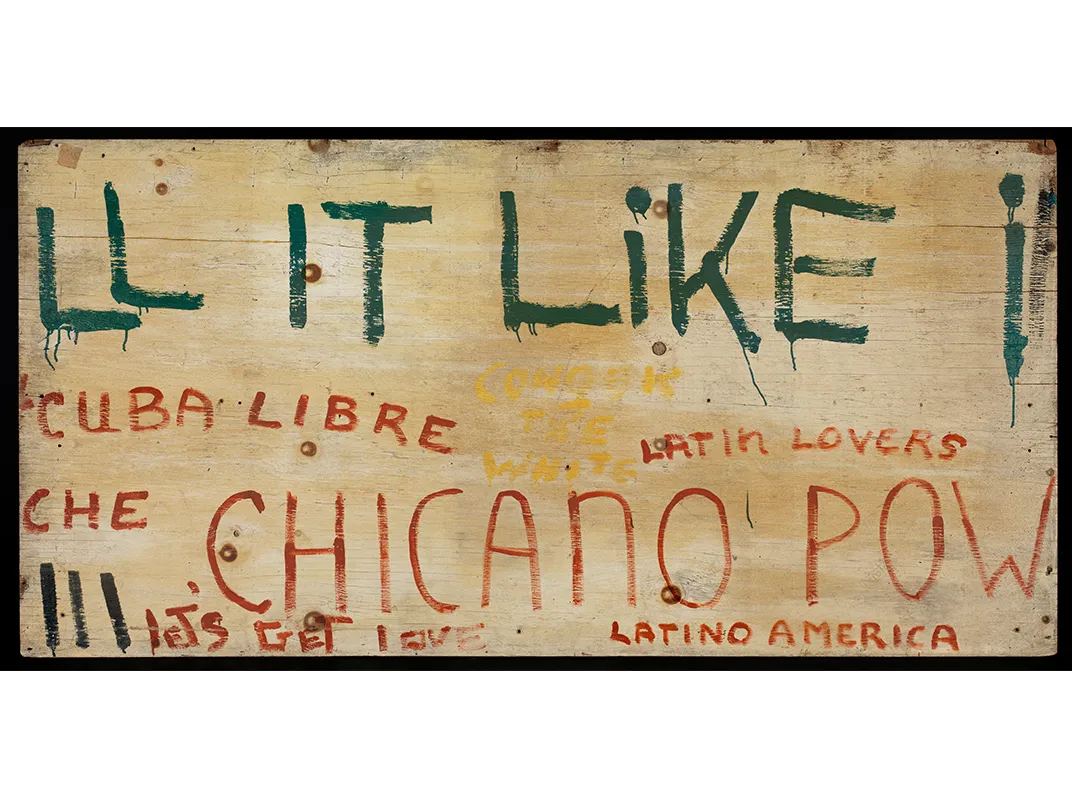

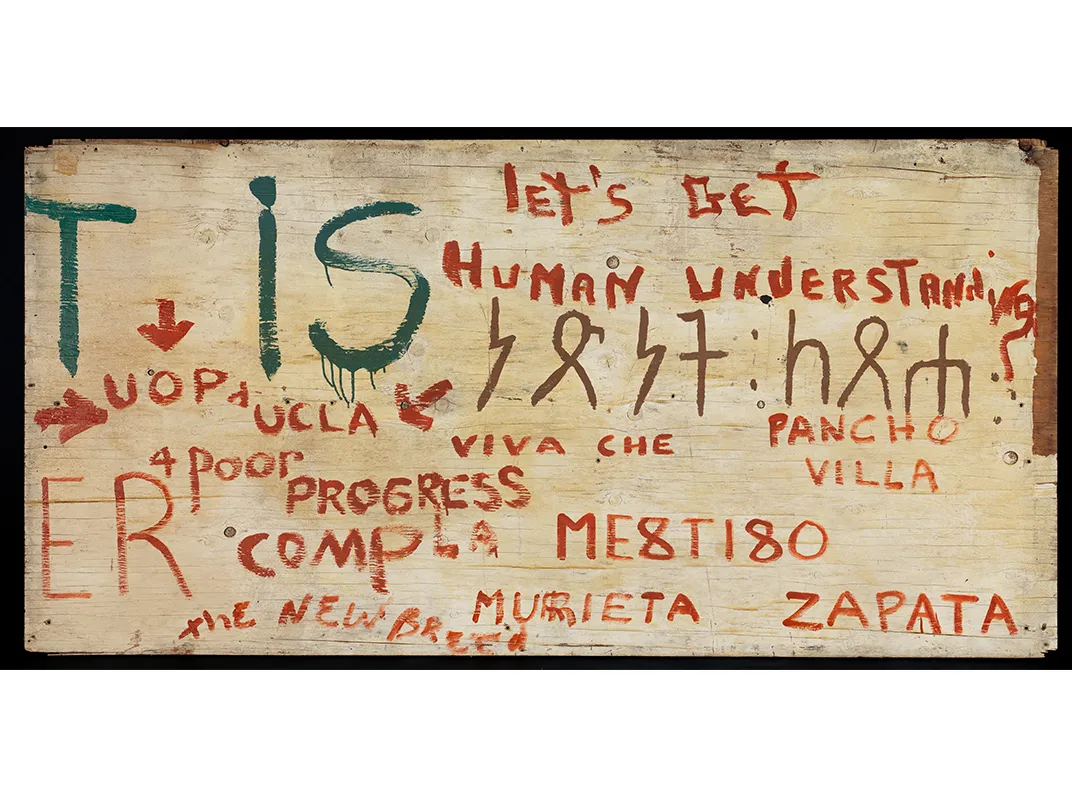

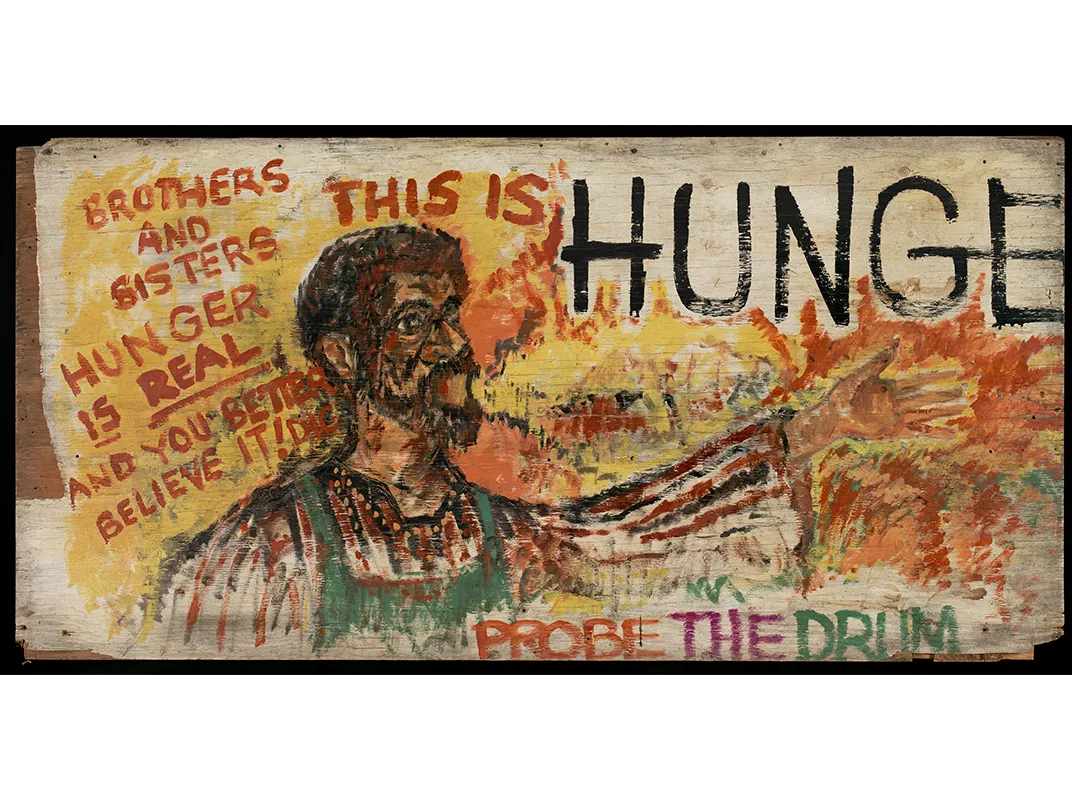

The words and images on what is known as “The Hunger Wall” are stark, but visceral. “Brothers and Sisters, Hunger is Real,” screams one panel in blood-red letters. “Chicano Power” and “Cuba Libre,” roars another. The voices are from some of the nearly 3,500 people who descended upon Washington D.C.’s National Mall in May, 1968 for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People's Campaign.

“People do make history, and many times what they do or what they say is not written down, particularly if it’s just the average Joe Blow,” says Vincent deForest, a Washington, D.C. activist who was working with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) at the time.

“We know the names of the great heroes written in books, but it’s the little people who also contribute. . . . How do we collect their artifacts? So that’s in the wall,” he says. “It is symbolic of these individuals whose names we may never know, but who were there and made sizeable contributions to what we were commemorating.”

“The Hunger Wall” was once part of a mural that was 32-feet long, 12-feet high and 12-feet wide. It made up one wall of what was called City Hall in Resurrection City, USA.” That’s the tent encampment that sprouted on the National Mall for six weeks, comprised of anti-poverty demonstrators supporting the Poor People’s Campaign. DeForest, now 80, saved a portion of the mural, and donated it to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The mural came from the largest building in the tent city, which had so many residents, the Postal Service issued it a zip code. The four eight-feet-by-four-feet panels ran horizontally along the top of 12 separate pieces of plywood that combined together into a enormous piece of art.

“That was the central location of staff and where press conferences were held outside,” explains deForest. “One side of the wall . . . became what we called ‘The Hunger Wall,’ where anybody living in the city or not living in the city could express themselves by putting their information on the wall.”

Throughout the six weeks that he spent in the tent city, deForest says he felt all along that the mural should be saved; particularly after having met so many people who were part of it.

“The leadership were being taped by the press, and written about by the press, and there were all of these other voices and expressions I thought were important too,” deForest adds. “The visual part really stirred me—the way in which individual people came to put their ideas or just express themselves in the way they did through the mechanism of the wall. ‘The Hunger Wall’ became their voice and I didn’t want that to be lost in memory.”

The thousands that converged on the National Mall from all over the United States were participating in perhaps King’s most ambitious vision, a campaign against poverty that brought together ethnic groups ranging from poor whites to Mexican-American activists to Black Civil Rights leaders to Native Americans. In January of 1968, King gave a speech supporting the move to expand on the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty into a broad national campaign.

“We are tired of being on the bottom,” King said. “We are tired of being exploited. We are tired of not being able to get adequate jobs. We are tired of not getting promotions after we get those jobs. As a result of our being tired, we are going to Washington D.C., the seat of our government, to engage in direct action for days and days, weeks and weeks, and months and months if necessary.”

The museum’s senior history curator William Pretzer says the key to the Poor People’s Campaign is that it was a multi-racial movement aimed at economic justice.

“The Poor People’s Campaign was initially conceived by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and he and the SCLC had put into motion the planning of it,” Pretzer says. “It wasn’t narrowly within civil rights legislation and it wasn’t African-American. It was explicitly ‘Let’s bring all the groups together because poverty is society-wide. Let’s bring all the groups together, come to Washington and create demonstrations and protests but also lobby directly around policies with our congressional representatives.’”

The SCLC drew upon a Economic and Social Bill of Rights, seeking $30 billion dollars for a poverty package including a meaningful job, a living wage, access to land and the ability to play a role in the government.

But King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, just prior to the planned beginning of the campaign. Caravans, a mule wagon train and bus trips were already set to start arriving in Washington, D.C. from nine cities, ranging from Selma to Los Angeles to El Paso to Chicago to Boston. At first, deForest remembers, SCLC leaders and King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, debated whether to delay the campaign.

“But it was decided that in honor of King and this revolutionary campaign that he decided upon, that we would move ahead,” deForest says. “The death of King . . . really released the kind of activism that I had never seen before, and everybody was willing to contribute something.”

The Rev. Dr. Bernard Lafayette was the national coordinator of the Poor People’s Campaign, and the SCLC’s new president, Rev. Ralph Abernathy pushed the start date back to May 12. He procured a temporary permit from the National Parks Service for an encampment of 3,000 people on the grassy area south of the reflecting pool. On that date, thousands streamed into Washington D.C. for a Mother’s Day March led by Coretta Scott King. Construction of Resurrection City began within days, after a very special ceremony.

“Recognizing that the land initially belonged to Native Americans, there was a ceremony where they gave us permission to use the Mall area for setting up this unique city for poor people. It was very impressive,” recalls deForest.

University of Maryland architect John Wiebenson mobilized his class, and other volunteers to come up with a way to house all of those people. The tents were created out of plywood, two-by-fours and canvas.

“They pre-fabbed the A-frame structure in a way that they could put it on a flatbed trailer truck, bring it to the Mall and then unload it and erect these frames along the mall,” deForest says.

Resurrection City had its own newspaper, the Soul Force, as well as an education center, and community center. Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. was elected mayor of the shantytown. DeForest says photographers, a film team from UCLA and even artists were sent to document the caravans coming in from all over the country. There was even a mule wagon train that came in from Marks, Mississippi.

“I think they started in Marks, because that was an area that turned King’s mind toward ‘We have to do something about poverty in this country.’ It was a very impoverished area and he was moved by what he saw,” deForest says, “so he decided that that would be one of the bench marks in the South.”

Reies Lopez Tijerina, who fought for the rights of Hispanics and Mexicans, led the Chicano (a word that became a point of pride for Mexican American Civil Rights activists despite its derogatory beginnings) contingent into the city from the West Coast. Tuscarora Chief Wallace (Mad Bear) Anderson was among the leaders of the Native American contingent.

“There were Native Americans, there were poor whites, there were women’s groups, the National Education Association, the teacher’s union participated,” Pretzer says, adding “a number of Chicanos came from L.A. and El Paso, so each of those different demographic groups were widely represented. College students, members of the Black Panthers, also some flat-out gang members from the Bronx and Chicago. There were just lots of different kind of people who came and stayed on the Mall. Lots of hippies too. These people might not have participated in the lobbying but they were there to express their opposition to poverty in general.”

There was a lot of lobbying. Activists met with congressmen and administrators in various departments including Treasury and State, and they held meetings and talked about legislation that could alleviate poverty. But there were serious challenges from the start. For one thing, the weather was a problem.

“It rained 30 to 40 days while we were putting up this city,” deForest recalls, “so it was unbelievable that the spirit of the community living in the city for that number of days was as high as it was.”

That, he says, was helped by visits from entertainers ranging from Nancy Wilson to Lou Rawls and Harry Belafonte. Marlon Brando participated and so did Burt Lancaster. But such a massive gathering required a lot of coordination between very different groups with very different needs.

“The policy needs of the Native American contingent didn’t correlate with what African-Americans were asking for, or the Chicano movement,” explains Pretzer. “There were political and logistical arguments within the community. There was no single set of goals anyone could subscribe to.”

On top of that, the muddy conditions made everything uncomfortable, and Pretzer says the public and the federal government didn’t respond very favorably. That brought disillusionment. Except on June 19, 1968, where organizers brought 50,000 people to the National Mall for Solidarity Day. It was Juneteenth—the oldest known celebration of the ending of slavery in the U.S.—and it was glorious. Demonstrators surrounded the Reflecting pool, sent up prayers for the poor, sang songs, and Coretta Scott King addressed the crowd.

But within days, there were reports of violence against passing motorists, and fire bombs. On June 23, police decided to move in with tear gas.

“A combination of Washington D.C. police and (National) Parks Service Police decided the encampment should end . . . and they went in with bulldozers . . .and picked up the material and dumped it,” says Pretzer.

Though the shantytown’s permit was set to expire on June 24, very few were aware of the plans to knock the city down the day before, says deForest.

“It was unannounced that they were going into the city to break it up . . . and word got back to us that night,” deForest recalls. “So we rushed down and we saw the workmen were just carting everything away. We didn’t know where they were going or anything. It was unbelievable. I was so angry I didn’t know what to do!”

DeForest and some friends found a pick-up truck, and discovered the materials were being taken to Fort Belvoir, a military installation in nearby Fairfax County, Virginia He says they went there, told officials they were part of SCLC and they needed the material they had removed from the camp. It had all been put into a warehouse, and some of it had been neatly packaged.

“There were people who were aware of the cultural worth of the material and they had selected out what they felt they wanted,” deForest says. “When I saw the portions of ‘The Hunger Wall,’ neatly packaged, we just went and got it, put it in the pickup and got out of there.”

At first, the mural was in deForest’s garage. Later, he began using it as a historic backdrop the work he and his brother Robert deForest were doing in preserving African-American historic sites. The organization was first known as the Afro American Bicentennial Corporation, and later became the Afro American Institute for Historic Preservation and Community Development.

“We worked on different projects, one of which was the study of historic sites, and we would feature different programs on African-American history,” says Vince deForest. “One of my favorites was the re-enactment of the Frederick Douglass 1852 speech in Rochester, New York. We would do this on the fourth of July.”

On July 5 that year, Douglass gave a speech on why blacks and slaves didn’t believe in celebrating Independence Day, because it would be the same as celebrating their enslavement. DeForest says they got actors to do that speech, including James Earl Jones, and it became very popular.

“On the fourth we’d be out on the Mall where everyone was watching fireworks and we’d pass out flyers announcing this event on the next day at the Frederick Douglass home—it’s got that hill that creates a natural amphitheater,” deForest recalls, adding that this was before the Visitor’s Center at site now was built. “We built a stage area at the bottom so people could come and sit on the hillside . . .and behind the stage I would put ‘The Hunger Wall,’ so that became the backdrop for the oration.”

Later, the mural was on display at the District of Columbia Historical Society. Pretzer says it was in storage there when the museum acquired it from deForest. He says the museum chose to focus on an event that happened in Washington, but was in fact the product of people from all over the country who came on this pilgrimage.

“It had quite a lot of influence because a lot of people in Washington saw this,” Pretzer says. “The civil rights movement had a couple of big successes with national legislation. But the question became ‘What are the new causes? How do we express these new causes?’ There was a lot of interest in Washington as to whether this national event could affect Marks, Mississippi.”

DeForest says when museum visitors see the mural, he wants them to remember something.

“The struggle, as we note every day in our newspapers around poverty and the dignity of the poor, is still with us. We have a constant reminder in the symbolic voice of the wall, that our work is not finished,” deForest says. “And the person who had the vision to create Resurrection City and the Poor People’s Campaign, is very much with us today.”

The Resurrection City Mural is on view in the National Museum of American History and Culture's inaugural exhibition "A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)