Nat Turner’s Bible Gave the Enslaved Rebel the Resolve to Rise Up

A Bible belonging to the enslaved Turner spoke of possibility says curator Rex Ellis of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/b4/23b40f29-e080-474b-92be-8cd15db595b1/turnerbibleweb.jpg)

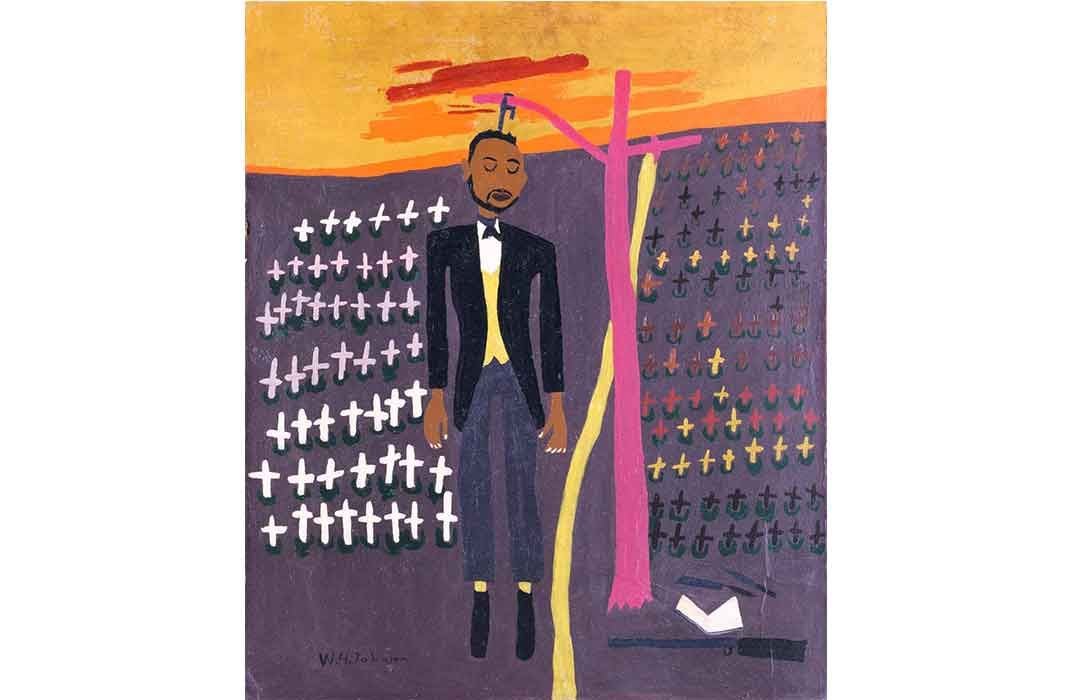

On November 5, 1831, when Judge Jeremiah Cobb, of Southampton County, Virginia, sentenced slave rebel Nat Turner to death by hanging, he ordered the Commonwealth to reimburse the estate of Turner’s slaughtered master. As confiscated chattel, Turner’s life was valued at $375. Six days later, the 30-year-old Turner was hanged and his body mutilated, but his powerful legacy transcended the punishments.

Almost 200 years later, Turner endures as a powerful symbol of uncompromising resistance to slavery, a latter-day voice insisting that Black Lives Matter.

His Bible, which he is believed to have been holding when he was captured, serves now as a centerpiece of the National Museum of African American History’s collection. The small volume—shorn of covers, part of its spine, and the Book of Revelations—will be on display when the museum opens on September 24, 2016. Turner is the subject of the new film The Birth of a Nation, which premiered in January at the Sundance Festival and broke a record for distribution rights, which sold for $17.5 million. The film is lately mired in controversy stemming from 1999 rape allegations against the film's director and star Nate Parker, yet some critics contend that the compelling drama should be judged on its own merits.

On August 21, 1831, Turner led a small group of conspirators from plantation to plantation, slaughtering unwary whites and rallying enslaved people. In less than two days, an estimated 60 whites—men, women and children—had been murdered before the rebels—a group that had swelled to more than 60 in number—were vanquished by local and state militia. In the rebellion’s immediate aftermath, more than 200 black men and women, enslaved and free, were executed.

Turner himself eluded capture for two months, time enough for the rebellion and its leader to generate Southern alarm and national attention. The rebellion had given firm lie to the self-serving myth that enslaved African-Americans were content and happy. Frightened by the rebellion, Southern whites, in turn, tightened their grip on enslaved and free blacks. Fearing for the safety of whites, legislators in the Virginia General Assembly engaged in a widely publicized and prolonged debate about ending slavery, an idea they ultimately rejected.

Turner’s Bible remained in the Southampton County courthouse storage until 1912, when a courthouse official presented it to members of the Person family, some of whose ancestors had been among the whites murdered by Turner and his fellow rebels.

In 2011, museum curator Rex Ellis drove to Southampton County, in southeastern Virginia, to examine the Bible and to meet with the prospective donors.

As Ellis wended through the countryside, he was struck by the landscape: an agrarian setting wholly inhospitable to any enslaved person’s dream of freedom. “The scope of what was set before Turner and every other enslaved person in that particular section of Virginia, in 1831, is still very obvious,” Ellis says. Fields upon fields, punctuated by the occasional farmhouse and bisected by long, lonely roads—nothing about the place suggested fun, recreation, life, or life enjoyed. “All I saw was work,” Ellis recalls.

The land, of course, supported a legal, social, and economic system designed to thwart freedom of movement, let alone mind. “Think about Turner’s situation and the situation of all enslaved people,” says Kenneth S. Greenberg, distinguished professor of history at Suffolk University in Boston. “They are denied weapons. If they leave their home farm, they need a note from their owner. If they try to run away, there is a system of armed patrols all over the South. If they make it to the North and their master can find them, the federal government is required to bring them back. The odds of escaping from slavery are stacked against African-Americans. Moreover, there is almost no chance of achieving freedom through rebellion. When someone makes a decision to engage in rebellion, they have to be willing to die. In fact, death is a virtual certainty. Very few people are willing to do that.”

Other forms of resistance posed less risk: slowing down the pace of work, breaking tools, setting places on fire. Slave rebellions, though few and small in size in America, were invariably bloody. Indeed, death was all but certain.

How, then, did Turner come to imagine—to believe in—something more than the confines of his particular time, place and lot in life? “When you are taught every day of your life, every hour of work that you produce, that you are there to service someone else, when every day you are controlled by the whims of someone else, and you are instructed to do exactly what you are told to do, and you do not have a great deal of individual expression—how do you break out of that?” Ellis asks.

But, atypically for an enslaved person, Turner knew how to read and write, and in the Bible he found an alternative: a suggestion that where he had begun was not where he needed to end. “That Bible didn’t represent normality; it represented possibility,” Ellis says. “I think the reason Turner carried it around with him, the reason it was dog-eared and careworn, is that it provided him with inspiration, with the possibility of something else for himself and for those around him.”

But Turner’s religious fervor—his visions, his revelations—has travelled a perilous distance from 1831 to today, inviting distortion and dismissal and bemusement. Today, the quality of faith that inspired Turner’s rebellion seems almost inaccessible. “His decision to rebel was inspired by religious visions,” Greenberg says. “It is difficult for a modern secular audience to connect with that.”

The moment Turner decided to make a move, Ellis suggests, he was free. “From that point on, he had broken the chains, the chains that bound him mentally—he had broken them. That’s a fabulously difficult thing to do.”

Nat Turner's Bible will be on view in the "Slavery and Freedom" exhibition when the National Museum of African American History and Culture opens on September 24, 2016.