National Zoo Mourns Death of Asian Elephant

The 72-year-old animal was the third oldest in the North American population

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/1a/381a7b06-3de9-4031-8e30-747d95b2b57b/20160323-02am.jpg)

Ambika, the beloved eldest member of the Smithsonian National Zoo’s Asian elephant herd, was euthanized yesterday, March 27, following a recent and irreversible decline in her health. The Zoo reports that Ambika’s age was estimated to be around 72 years, making her the third oldest Asian elephant in the North American population. She lived longer by almost three decades than other female Asian elephants under human care.

In a recent article by Michael E. Ruane in the Washington Post, describing the arduous and careful task of determining when an elephant’s advancing age and illnesses require euthanasia, the Zoo’s chief veterinarian Don Neiffer said: “when you get to the point when the animal can’t be made comfortable, can’t interact with its herdmates, can’t move around its enclosure, . . . honestly, we shouldn’t even be at that point. We should have made our call well before that.”

In a release, the Zoo reported that last week: “Keepers noticed that Ambika’s right-front leg, which bore the brunt of her weight, developed a curve that weakened her ability to stand. Though she had some good days and some bad days, staff grew concerned when she chose not to explore her habitat as much as she normally would or engage with her keepers or elephant companions, Shanthi and Bozie. In discussing Ambika’s overall quality of life, the elephant and veterinary team strongly considered Ambika’s gait, blood-work parameters, radiographs, progressions of her lesions and her tendency to occasionally isolate from Shanthi and Bozie. Given her extremely old age, decline, physically and socially, and poor long-term prognosis, they felt they had exhausted all treatment options and made the decision to humanely euthanize her.”

Steven Monfort, the Zoo’s director, announced the animal’s death this morning, noting her extraordinary legacy: “Ambika truly was a giant among our conservation community. For the past five decades, Ambika served as both an ambassador and a pioneer for her species. It is not an exaggeration to say that much of what scientists know about Asian elephant biology, behavior, reproduction and ecology is thanks to Ambika’s participation in our conservation-research studies. Firsthand, she helped shape the collective knowledge of what elephants need to survive and thrive both in human care and the wild. Her extraordinary legacy and longevity are a testament to our team, whose professionalism and dedication to Ambika’s well-being and quality of life exemplifies the critical work our community does to save these animals from extinction.”

Keepers, who often mourn their animals as friends and family, described Ambika as having a “sense of humor” especially at mealtimes. She was a “persnickety eater,” who would arrange her grains to her liking before eating.

The Zoo’s release described how elephant and veterinary teams met regularly to discuss Ambika’s overall health and ongoing treatments. In her late 60s, the elephant had developed and undergone treatment for osteoarthritis, a condition that is incurable, but treatable.

Anti-inflammatories, analgesic medications and various joint supplements helped to ease Ambika’s pain and slowed the progression of the disease. Unfortunately, Ambika also developed lesions on her footpads and nails. Regular foot baths and pedicures, topical medications, and oral and topical antibiotics were used to treat these issues. “Although the animal care team tried multiple methods of husbandry management and medical treatments,” according to the release, “they were unable to successfully control and prevent further progression of the lesions.”

Ambika’s euthanasia took place in the Elephant Barn. The Zoo’s other elephants Shanthi and Bozie, who had long bonded with the elderly female, were not present for the procedure, but were offered time to be with their deceased herd mate.

Scientists have long suggested that elephants undergo a grieving process that includes the exploring of the body as recognition of the death. “Elephants will commonly touch the temporal glands, ear canal, mouth and trunk tip. Often, they will make a rumble vocalization while inspecting the body,” said the Zoo’s release.

“For approximately 15 to 20 minutes, Shanthi and Bozie walked around Ambika. They sniffed and touched her with their trunks. Although the pair usually communicate with squeaks, honks and trumpets, they were fairly quiet during this encounter.”

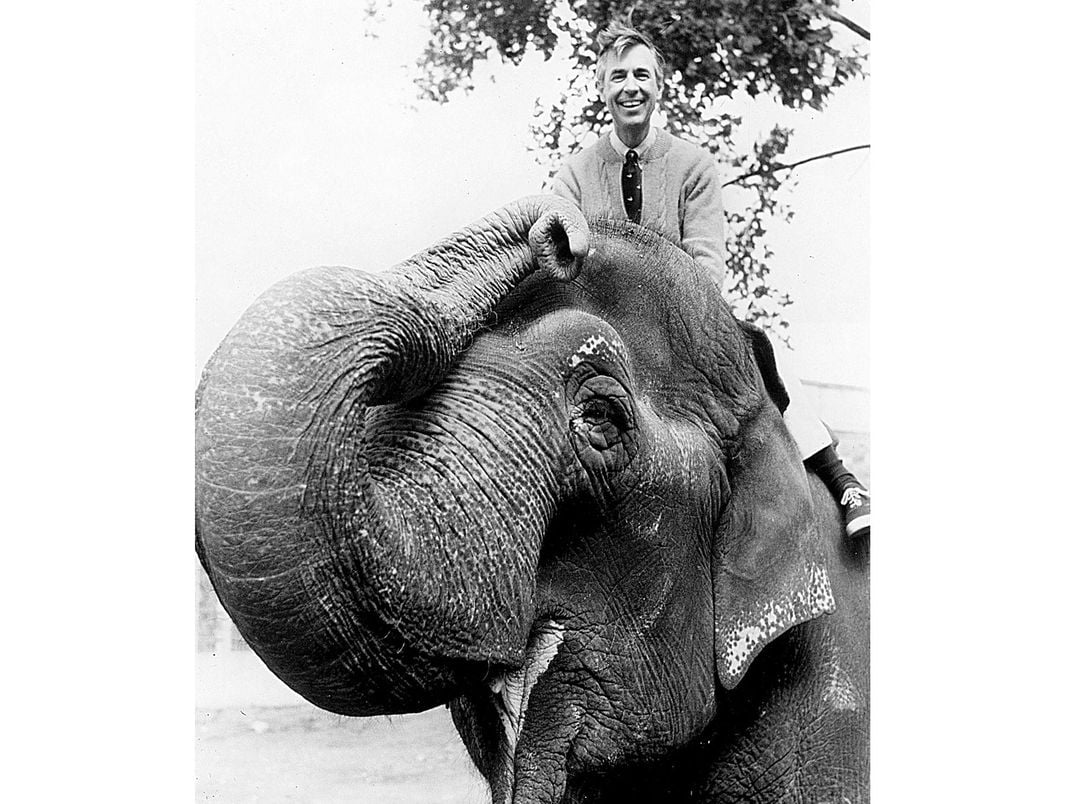

Ambika was born in India around 1948, and captured in the Coorg forest at about age 8, and used as a logging elephant until 1961. She came to the Zoo as a gift from the children of India.

According to the release, Ambika was one of the most researched elephants in the world. Keepers trained her to voluntarily participate in daily husbandry care and medical procedures, allowing animal care staff to routinely monitor her health—allowing “opportunity to help Zoo scientists better understand the behavior, biology, reproduction and ecology of Asian elephants.”

“Ambika routinely allowed staff to collect blood samples for the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s endocrine lab to study cortisol levels, participated in studies that assessed elephant vocalizations and enrichment preferences, and enabled veterinarians to take carpal and toe radiographs to study the onset and progression of osteoarthritis,” said the release.

“Most notably, Ambika was the first elephant to receive the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) vaccine to prevent leiomyomas—fibroids in the uterus—which are a known cause of mortality in Asian elephants in human care.”

As a public health precaution due to COVID-19, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute is temporarily closed to the public. Upon reopening, visitors to the Elephant Trails habitat can view the Zoo’s male elephant, Spike, and five female elephants: Shanthi, Bozie, Kamala, Swarna and Maharani. Meantime, visitors to the Zoo’s website can watch them on the Elephant Cam.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)