A Native American Community in Baltimore Reclaims Its History

Thousands of Lumbee Indians, members of the largest tribe east of the Mississippi, once lived in the neighborhoods of Upper Fells Point and Washington Hill

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/75/ba751564-1e15-4f96-935f-5c12a3018a8a/gettyimages-1162779727.jpg)

One chilly March afternoon in 2018, Ashley Minner, a community artist, folklorist, professor and enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, gathered the elders together for a luncheon at Vinny’s, an Italian eatery on the outskirts of Baltimore. The group crowded around a family-style table, eager to chat with friends after a long winter. Over a dessert of cannoli and Minner’s homemade banana pudding, she got down to business to show the group what she had found—a 1969 federally commissioned map of the Lumbee Indian community in Baltimore as it stood in its heyday.

Her discovery was met with bewildered expressions.

“The elders said, ‘This is wrong. This is all wrong.’ They couldn’t even fix it,” Minner recalls from her seat at a large oak desk in Hornbake Library’s Special Collections room. When she speaks, she embodies a down-to-earth, solid presence, with an air of humility that her University of Maryland students will tell you is how she conducts her classes. That day, she wore no jewelry or makeup, just a T-shirt, jeans and a bright purple windbreaker.

At the luncheon, plates were cleared but questions remained. The elders drafted a rough sketch of the neighborhood based on their recollections. Now it was Minner’s turn to be perplexed. Though she has lived all her life in the Baltimore area, nothing looked remotely familiar.

“It wasn’t until my Aunt Jeanette took me to Baltimore Street, and pointed and said, ‘This is where I used to live,’ that I realized the reason I wasn’t getting it was because it’s a park now. The whole landscape has been transformed.”

Baltimore may be famous for John Waters, Edgar Allan Poe, and steamed crabs, but very few people are aware that there was once a sizeable population of American Indians, the Lumbee tribe, who lived in the neighborhoods of Upper Fells Point and Washington Hill. By the 1960s, there were so many Native Americans living in the area that many Lumbee affectionately referred to it as “The Reservation.” In the early 1970s, this part of Baltimore underwent a massive urban renewal development project and many Lumbee residences were destroyed, including most of the 1700 block of East Baltimore Street. “Almost every Lumbee-occupied space was turned into a vacant lot or a green space,” Minner says. The population of “The Reservation” continued to decrease between 1970 and 1980, when thousands of Baltimoreans moved out of the city to Baltimore County, including many Lumbee.

Now, Minner, age 37, is embarking on a mission to share their stories with the world. In conjunction with her Ph.D. research and with the support of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, she is creating an archive devoted to her community, including a more accurate map of how the neighborhood used to be, so that their contributions to the city’s cultural legacy will be rendered visible to history.

The Lumbee are the largest tribe east of the Mississippi and the ninth largest in the country. They derive their name from the Lumbee River that flows through tribal territory in Robeson, Cumberland, Hoke and Scotland counties of North Carolina. They descend from Iroquoian, Siouan and Algonquian speaking people, who settled in the area and formed a cohesive community, seeking refuge from disease, colonial warfare and enslavement. Some intermarried with non-Indigenous peoples, including whites and blacks. After World War II, thousands of Lumbee moved north to cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia and Detroit, seeking work and eager to escape Jim Crow segregation. They traded the back-breaking labor of sharecropping for jobs in factories, construction and the service industry. Many also became small business owners.

The Lumbee have fought unsuccessfully for full federal recognition from the U.S. government since 1888. Congress passed the Lumbee Act in 1956, which recognized the tribe as Native American. However, it did not give them full federal recognition, which grants access to federal funds and other rights. A bi-partisan bill called the Lumbee Recognition Act is now pending before Congress.

The historically mixed-race heritage of the Lumbee has played a role in the government’s denial of recognition, and marginalization at the federal level has a trickle-down effect. Many Lumbee in Baltimore, like members of other tribes living in urban areas across the country, suffer from cases of “mistaken identity.”

“I’ve been called Asian, Puerto Rican, Hawaiian—everything but what I am,” Minner says. “Then you tell people that you’re Indian, and they say, ‘No, you’re not.’ It does something to you psychologically to have people not accept you for who you are day in and day out.” Minner is Lumbee on her mother’s side and Anglo-American on her father’s side. Her husband, Thomas, is Lumbee and African American.

When the elders said their goodbyes at the restaurant, they promised to meet again to help Minner with her research. Over the weeks and months that followed, Minner and some of the elders revisited the streets of Upper Fells Point. As with Proust’s madeleine, sometimes all it took was sitting on a particular porch or standing on a familiar street corner for the floodgates of memory to open.

“It’s phenomenological. You re-embody the space and you re-remember,” Minner explains.

They pointed out the phantoms of once-upon-a-time buildings. Sid’s Ranch House, a famous Lumbee hangout, is now a vacant lot. A former Lumbee carryout restaurant has been replaced by Tacos Jalisco. South Broadway Baptist Church at 211 S. Broadway still stands and serves as one of the last anchor points for the Lumbee, who remain in the city.

Minner’s deep dive into Lumbee history started with her own family. While still in high school, she recorded her grandfather’s memories of Baltimore and North Carolina. “I guess it’s that fear of loss and knowing that people aren’t around forever,” Minner said, reflecting on what prompted her to document his stories. Elaine Eff, a former Maryland state folklorist and one of Minner’s mentors, said that Minner is in a unique position to document the Lumbee. “An outsider just wouldn’t understand the nuances of the culture,” she said. “Ashley straddles both worlds.”

By collaborating with the elders, Minner is offering them the opportunity to decide how their personal and collective history will be presented.

“I began working on this project [thinking] there were no records,” Minner says, surrounded by boxes of old photographs and stacks of phone directories. Preeminent Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery, who sat on Minner’s dissertation committee, reassured Minner that she could find proof of the Lumbee’s extensive presence in Baltimore. After all, they had home addresses and telephone numbers like every other Baltimorean. Lowery advised Minner to look through census records, newspaper articles and city directories in local archives.

After examining multiple articles and the census records, Minner discovered that pinpointing the exact number of Lumbee in Baltimore during the 1950s and 60s when the community was at its peak was more complex than she had anticipated. According to the researcher who produced the 1969 map, John Gregory Peck, the census records at that time only distinguished between “whites” and “non-whites.” The Lumbee were classified as white; for outsiders, Lumbee have continually defied racial categorization.

“We run the gamut of skin colors, eye colors and hair textures,” Minner says. “When the Lumbee came to Baltimore, Westerns were all the rage. But we didn’t look like the Indians on TV.” Despite many success stories, the Lumbee community in Baltimore has struggled with illiteracy, poverty and criminal incidents. Minner acknowledges that historical accounts tend to highlight the problems the Lumbee have faced but also emphasize the darker aspects of their story. “The older articles are often really negative. It’s always about a knife fight or a gun fight,” Minner says, referring to news clippings she has compiled, some of which feature crimes allegedly perpetrated by Lumbee.

In addition to materials sourced from city and state archives, Minner’s new Lumbee archive will include oral histories and contributions from elders’ personal collections. She is quick to point out that acting as both a tribal member and scholar can make determining “how much to sanitize the ugly things” a challenge.

The Lumbee archive will be housed at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Minner’s compilation created with Lumbee elders will form the backbone of the collection. She believes the collection could take as long as five years to assemble. A digital version of the Lumbee archive will be accessible through the Baltimore American Indian Center in addition to UMBC, so that community members can conduct their own research. Elaine Eff also stressed the importance of the archive being widely known and accessible. “The fact that the archive is going to UMBC in Special Collections is significant,” Eff said. “It means that it can be a jumping-off point for other projects on the Lumbee.”

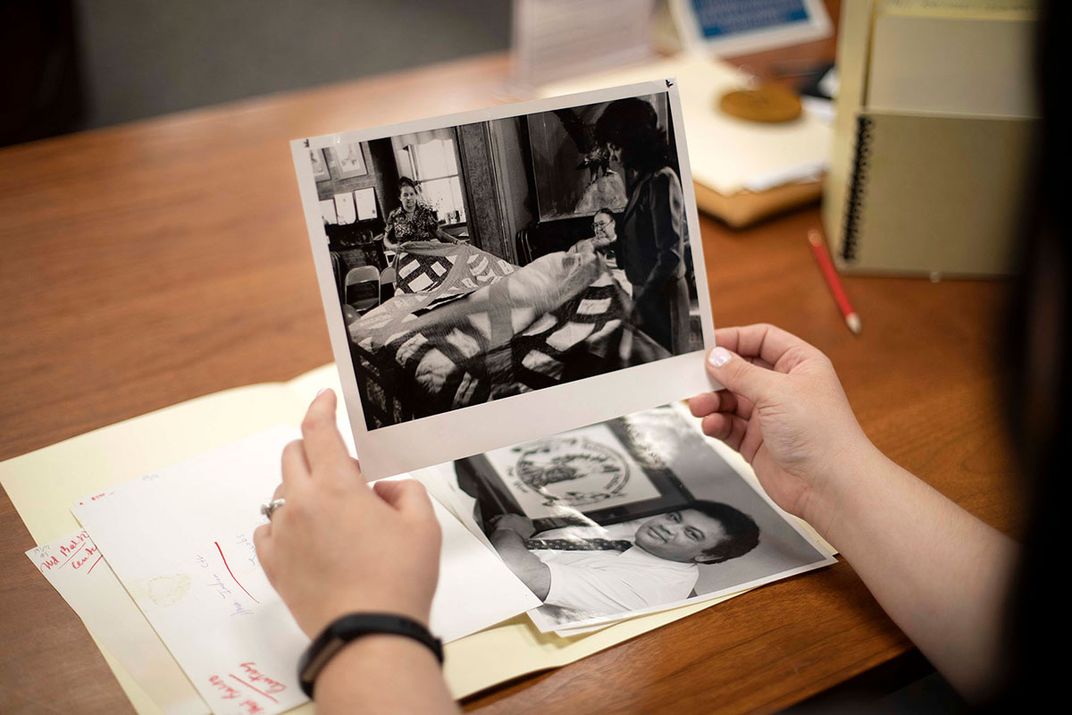

“I couldn’t do any of this on my own,” Minner says, as she opens a box of photos from the Baltimore News American archive. “Most of the elders are in their 70s, and they are the greatest resource available to anybody right now about what we had here.”

When she discovers a photo or an old newspaper clipping that corresponds with an elders’ story, Minner gets excited. “Many times they don’t know they’re in the archives. I’ll take pictures and show them what I found, like, ‘Look where you were living in 1958!’”

“This is sister Dosha,” Minner says, selecting a photo of a jovial, silver-haired woman presenting a pot of fish to the camera with the pride of a new grandparent. “She had a beautiful voice and her song was ‘How Great Thou Art.’” She picks another photo from the folder, featuring a taxidermy eagle posed menacingly behind three women who grasp opposite ends of a quilt as if preparing for the bird to nose-dive into the center. “That’s Alme Jones,” she says, pointing to an elder wearing oversized spectacles. “She was my husband’s grandmother.”

Next, Minner opens a massive R.L. Polk directory and begins searching for Lumbee names that correspond with addresses in Upper Fells Point. “In the 1950s, it’s still kind of a mix. We can see some Jewish names, Polish names.” She carefully turns the delicate pages, scanning the list of diminutive print. “There’s a Locklear. Here’s a Hunt,” she says. “As it gets into the 60s, all the names become Lumbee. There’s a Revels, Chavis…”

The Lumbee have a handful of common last names that make them easily distinguishable—to another Lumbee, at least. She finds the 1700 block of Baltimore Street, the heart of “The Reservation.”

“And that’s where my Aunt Jeanette lived, right there, on Irvine Place,” says Minner.

Jeanette W. Jones sits next to her niece on the couch at Jones’s home in Dundalk, Baltimore County. The side table is crowded with a collection of porcelain and glass angels. A white cross hanging in the doorway between the living room and kitchen says, “God Protect This Family.” Minner says Jones has been “front and center” in her research and a source of inspiration for the archive project.

“I told Ashley, you’ve got to know your people.” Jones speaks in a deep baritone, her Robeson County lilt adding bounce and verve to the words. She has a stern gaze which flickers warm when she laughs and an air of authority harking back to her days as an educator in the public-school system.

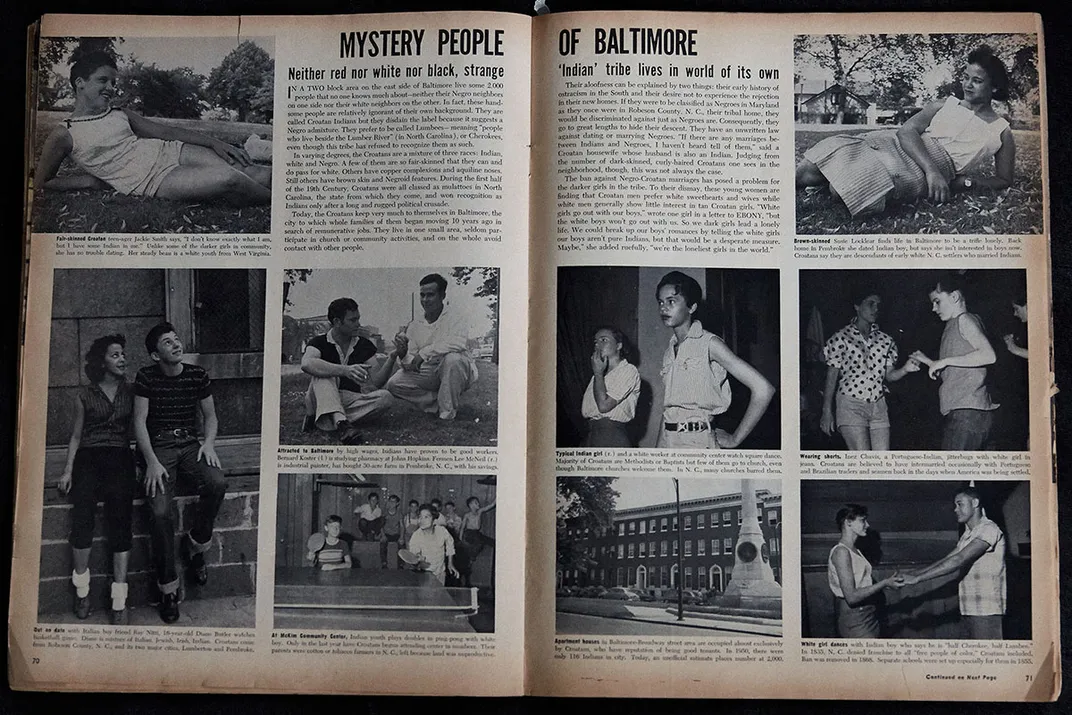

One of the many accounts of racial prejudice that Minner has recorded for the Lumbee archive features Jones. In 1957, a journalist and a photographer from Ebony Magazine were sent to document Lumbee of Baltimore—deemed “mysterious” by the magazine. Unbeknownst to Jones, a photo of her as a 14-year-old attending a youth dance was featured in the spread, with the caption, “Typical Indian girl.” The headline of the article read: “Mystery People of Baltimore: Neither red nor white nor black, strange “Indian” tribe lives in world of its own.”

Despite being a publication written and published by people of color, Minner points out that the tone of the article was derogatory. “They were trying to understand us within a racial binary where people can only be black or white. They probably thought, ‘Well they look black-adjacent, but we’re not sure.’”

Jones made it her mission when she directed the Indian Education program in the Baltimore Public School District to instill pride in Native students. She advocated for college scholarships for Native Americans, created an Indigenous Peoples library with books on Native cultures, and provided one-on-one tutoring for struggling students. She was equally determined to expose her niece to the richness of her Lumbee heritage. She took Minner to culture classes at the Baltimore American Indian Center, taught her traditional recipes, and invited her to Native American-themed field trips with her students.

When she graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art with her BFA in fine art, Minner discovered she too had a passion for working with Lumbee youth. Jones groomed her niece to take over her job with Indian Education. Minner devoted 12 years to working in the school district. During that time, she also founded and directed a successful after-school art program for Native American youth and earned two master’s degrees. Eventually, the low pay and daily challenges of working as a community advocate began to affect her health. Minner felt guilty about quitting, but Jones encouraged her to move on and advance her career.

“I didn’t have kids. I had a family to help support me,” Minner says, settling back into her aunt’s plethora of sofa pillows. “A lot of things made it possible for me to spend that much time and give that much of myself. Most people in our community can’t. They’re just not in a position to.”

“She’s educating people beyond the classroom,” Jones says. “She’s surpassed me now.”

They lead the way to the “Indian room” of her home, as Jones calls it, aptly named for its assortment of Native American themed trinkets and traditional handicrafts. The mantelpiece is adorned with Hummel-esque statuettes of Plains women wearing buckskin dresses and feathered headbands. A bow and arrow are mounted on the wall, along with family photos and an oil painting of teepees. Heyman Jones, Jeanette Jones’s husband of four years, is watching TV. He wears a plaid flannel shirt and a red baseball cap with the Lumbee tribal insignia. At 82-years-old, he possesses the spirit and stride of a much younger man.

“He’s a newlywed,” Minner quips, as if to explain his boyish enthusiasm. “They go everywhere together. Wear matching outfits.”

“Mr. Heyman” grew up in North Carolina and moved to Baltimore as a young man to work at General Motors. He bounds out of the chair to show off a group photo of his family at his father’s house during Homecoming, when Lumbee gather together for barbecue, church hymns, a parade, a powwow and other activities.

“Mr. Heyman’s father was a famous singer,” Minner says.

“Would you like to hear one of his songs?” Mr. Heyman inquires, and after a resounding yes, he opens the sliding glass door to the backyard to retrieve a CD from the garage.

“He just went right out in the rain!” says Minner, shaking her head and smiling. Back inside, Mr. Heyman, his shoulders damp with rain, places the CD in the player and turns the volume up full blast. First, a tinny piano chord intro, then a swell of voices layered in perfect harmony. Finally, his father’s high tenor solo, bright and clear, vaults over the other singers as he belts out, “Lord, I’ve been a hardworking pilgrim.” The den in Dundalk is momentarily filled with the sounds of the beloved Lumbee church of his childhood in North Carolina.

“He always sang for the lord,” Mr. Heyman says, his voice choked with emotion as he remembers attending church with his father. “He was a deeply religious man. He’d be out working in the field, and if somebody passed away, they’d call him in to come sing at the funeral.”

Minner and Jones exchange a glance, as if they’ve heard this story many times before.

According to Minner, Mr. Heyman knows everyone, both in North Carolina and in Baltimore. He’s like a walking, talking family tree—an invaluable repository of knowledge about Lumbee family ties.

Jones and Minner no longer work in the public-school system, but Minner has discovered a different way to give back to Lumbee youth. She is creating a bridge between the past and the present, the seniors and the teens, through the power of collective memory.

“Our young people can be particularly unmoored,” Minner says. “There are all kinds of ways society makes you feel like you don’t belong. I think when you realize that your history is much deeper than what you knew, it gives you a different sense of belonging. I think this [archive] project could help with that. We are part of a long, rich history. We helped build this city. We helped develop the character it has now. It’s ours too.”

A version of the article was originally published by the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.