When Osage textile and ceramic artist Anita Fields was in her early 20s, she learned how to craft ribbon work by attending weekly informal gatherings at the Osage Nation Museum in Pawhuska, Oklahoma—the oldest of its kind in the United States. During these classes, fellow women in the community handed Fields four different colored cotton strips—ribbon was too expensive for beginners—and taught the budding artist how to sew loose basting stitches and draw a mirrored design down the full length of each strip. Slowly, Fields snipped and turned the faux-ribbon corners under, revealing what looked like a reverse appliqué with colorful layers of fabric underneath.

But these teachings were not the average class at a community center, Fields notes. Each gathering was intimate—filled with lunch, laughter, television and asking the elders questions about different ribbon work and finger-weaving techniques.

“It wasn’t just the practice they were sharing with us, it was doing little things and helping one another out in a way that was traditional,” Fields says. “They were imparting wonderful information about how to be an Osage woman through showing us the way of being.”

Fields continued to seek out the creators and makers, who were usually women, in her community, using their guidance to ultimately inspire the creation of her pink-and-blue Osage Wedding Coat titled, It’s in Our DNA, It’s Who We Are, featured in the 2020-2021 traveling exhibition “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists.”

Looking at the work closely, one can find Fields honoring what she calls a “continuum of knowledge”—the passing on from one generation to the next; her own detailed ribbon work is located on the cuff of each sleeve and a small placket on the back.

The piece originates from a military style coat that dates back to the 1700s, Fields says. For Osage people, this article of clothing was a form of gifts and exchanges when delegations began interacting with U.S. government officials. But because the men were too big to fit into the coats, they passed them over to the women to transform into an Osage aesthetic for arranged wedding ceremonies. This practice continued until the early 1950s. After organized marriages decreased, the coat became important to the tribe’s In-Lon-Schka, or ceremonial dance. Now they’re used as a way to “Pay for the Drum;” the previous Osage drum keeper’s family receives a wedding coat and hat after taking care of the instrument for many years.

The work addresses much of the Osage community’s ongoing history. On the coat’s interior, Fields digitally printed photos of historic moments, documents, ethnology reports and even her great-grandfather. She embroidered DNA patterns, Osage orthography and sun symbols to decorate the piece’s surface. And while the outside appears identifiable—a coat—the inside reveals a deeper history that recognizes the Native women who continue to carry on the traditions and customs of the Osage people.

“Our history has been so suppressed; It has been told from one side,” Fields says. “Now we have the opportunity to speak about where we come from and who we are.”

“Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists” marks the first major exhibition dedicated to celebrating Native women artists. The show is on the third stop of a four venue national tour at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 crisis) before moving on to the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The exhibition, featuring 82 artworks that span more than a thousand years, grounds Indigenous women into the art world, and explores the work of 115 artists of Native nations from the United States and Canada. Each piece tells a story of the creative forces—often the mothers, grandmothers, aunts and sisters—behind Native American art, and provides a long-overdue space for the representation and attribution of individual cultures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/d2/81d2a503-7cec-45fa-9eb5-684c8b83b01a/begay_winter_in_the_north.jpg)

“It was really important for us to non-anonymize these women, to tell the story about their complex lives,” says Jill Ahlberg Yohe, an associate curator of Native American Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and one of the two organizers of the exhibition. “In many ways, some of these women were not master artists, but they were diplomats, entrepreneurs and formidable women.”

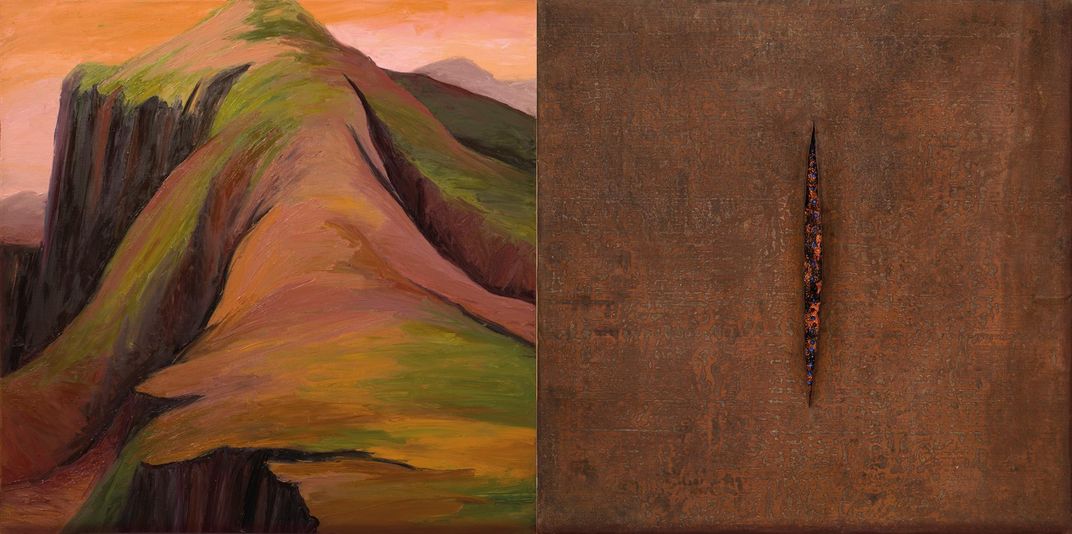

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/a0/7ea02a61-78f3-489d-97f4-455b4d9c2e0f/belcourt_wisdom_of_the_universe.jpg)

No two pieces are alike; the thematic show reflects an ongoing tradition, but it also provides a response to today’s changing world. Visitors can view a variety of media including textiles—such as Navajo artist D.Y. Begay’s Southwest landscape painting on wool—beadwork, sculpture, photography, film and even clothing attire such as beaded and quilled Louboutin shoes. The curators organized the show under the themes of “Legacy,” “Relationships” and “Power,” with accompanying videos of in-depth interviews with the contributing artists. To illuminate the different identities throughout the show, viewers can find panel descriptions in both English and each artist’s Native language.

But at the core of “Hearts of Our People” is its collaborative process. In 2015, Yohe and Teri Greeves organized the Native Exhibition Advisory Board, a panel of 21 Native women artists, curators, art historians and non-Native scholars from across North America, to give a wide range of nations a voice during the formation of the show. This radical shift in methodology not only defined the exhibition’s objectives, but it also eliminated an engrained hierarchy often found in the curatorial process.

“It was really incredibly important to create an advisory board of women who could speak for themselves,” says Greeves, an independent curator and member of the Kiowa Nation. “To have that ability to speak for their communities and for artists in the community.”

And as a result, the exhibition’s artists have found unique ways to weave their own Native identities into the show’s larger narrative. Kelly Church, an Ottawa and Pottawatomi artist and educator wove a green and copper egg—a metaphor for new life and fertility—from the fibers of her nation’s forest to emphasize the continuance of cultural teachings and preservation. This Fabergé-like vessel speaks to her nation’s tradition of basket-weaving; Church and fellow community members relied on the black ash tree to bring the teaching to life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/98/ae98b3fc-0921-48a1-b48c-38762bc4ef10/kelly_church_-_sustaining_traditions.jpg)

But after the emerald ash borer, a green Asian beetle with a copper belly, decimated millions of ash trees, Church became an advocate for preserving a traditional resource. “I was looking ahead to the future—if we really lose all of our ash resource, we lose the tradition that we’ve held onto for so long,” Church says. “My life turned into being an activist for saving the ash trees and creating pieces to speak about that story.”

The work speaks to both the cultural teachings of Church’s ancestors and the reliance of technology to preserve a centuries-old practice. On the outside, copper pieces interlace the green basket, reflecting both the color of the emerald ash borer as well as the traditionally harvested materials of copper and black ash. Church placed a flash drive and a vial containing an emerald ash borer inside the egg—showing future generations how to bring back the black ash teachings in case they disappear.

Reflected throughout “Hearts of Our People,” are stories of devastation, hardship and resilience. A life-sized lightbox image called Fringe, for example, shows a half-nude woman lying on her side and turned away from the camera; a gash protrudes across her back, sewed up by strings of blood-red beads. Rebecca Belmore, an Anishinaabe artist, created the wound with special effects makeup to reinforce the violence and economic injustice placed upon First Nations people. Symbolizing Indigenous strength and healing, she seems to be saying that Native women have the power—in their hands—to stitch lives back together.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/9f/c39f2e75-4914-4832-a2fd-f461257eb248/belmore_fringe.jpg)

And tucked away in the corner room of the exhibition is a last-minute, yet vital addition to the exhibition: Marianne Nicolson’s Container for Souls. A clear bentwood box houses a light that brightens a dark room. The piece is carved with both animals and plants, and along the side are photographs of the artist’s family. The inner light casts a shadow on all four walls, as visitors can simultaneously experience being both inside and outside of the box.

Nicolson, a Kwakwaka’wakw and Dzawada’enuxw artist, uses the light in the bentwood box to show how viewers’ bodies interrupt the illumination and cast a shadow upon the wall—referencing colonialism and the takeover of Kwakwaka’wakw bodies and lands in 1792.

“We now become a part of this,” Greeves says, speaking from her knowledge of Nicolson’s community. “Our people have been the reflection upon which Americans have created an identity… We are you and you are us—you are not American without us.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/66/046649a0-686d-408e-8cf0-c935e1ba1480/marianne_nicolson__bax_w_anatsi_the_container_for_souls.jpg)

Forging individual identities is a crucial thread to “Hearts of Our People.” And Native women artists are at the forefront of reshaping their narrative through honoring the strength of those that came before.

“We’ve been held back in a lot of ways,” Church says. “But it was also about them [Native people] being strong enough and recognizing that that was their way, but this is our road.”

And the path continues to be forged; Yohe hopes that “Hearts of Our People” inspires a future of significant shows that include both historic and contemporary Native art. Even a wide breadth of pieces only skims the surface—ongoing exhibitions must provide a platform for Native people to speak for themselves and to share their nation’s ongoing knowledge.

“The continuum keeps our culture moving,” Fields says. “The makers and the creators are keeping things alive.”

After its appearance at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the exhibition, “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists” , traveled to the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where it was on view through January 3, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/54/b554b714-e23e-40e7-9c46-a502c06fa696/mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/60/ca60cb8b-87cb-42ec-8a02-6458b90bcda7/main_longform.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)