Never Mind Her Stellar Jazz Career, Young Ella Fitzgerald Just Wanted to Dance

The preeminent vocalist didn’t actually start out as a singer

:focal(487x219:488x220)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ad/f3/adf3207b-2328-4336-bc39-47ef2a325a72/ac0584-0000063.jpg)

In her songs, no one could tell a story better than Ella Fitzgerald. Her phrasing made us believe in Cole Porter's words: "Night and day, you are the one/Only you beneath the moon or under the sun," or personally experience Ira Gershwin's plea: "There's a somebody I'm longing to see/I hope that he turns out to be/Someone who'll watch over me."

But she actually did not begin her career as a singer. In 1934, at the Apollo Theater’s Amateur Night contest, her name was pulled in a weekly drawing to compete. The 17-year-old Fitzgerald was going to audition as a dancer, but a remarkable dance act just ahead of her was such a success that she changed her mind and decided to sing “Judy” by composer Hoagy Carmichael.

The song was one of her mother's favorites; so she knew it well from a recording by Connee Boswell, and her sisters Martha and Helvetia. When the audience demanded an encore, Ella sang the flip side of the Boswell Sisters’ record, “The Object of My Affection.” These were the only two songs she knew, but she won the contest. Jazz bandleader Chick Webb soon asked the young singer to join his orchestra.

Ella Fitzgerald’s centennial birthday on April 25 is sparking a joyful celebration of the legendary jazz singer’s life and career around the Smithsonian. The National Museum of American History will open an exhibition, “Ella Fitzgerald: The First Lady of Song at 100,” on April 1, and the Smithsonian’s 16th Annual Jazz Appreciation Month is showcasing her contribution in several performances. And the National Portrait Gallery is displaying for the first time a recent acquisition—a William Gottlieb photograph of Fitzgerald in performance with Ray Brown, Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Jackson.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/1b/7d1bcc82-4f00-45e3-a758-cd212c30347e/npg201660fitzgeraldrweb.jpg)

“The First Lady of Song” exhibition will draw on the museum’s vast Ella Fitzgerald collection, including personal effects, artifacts and photographs that she bequeathed to the museum. Her 1979 Kennedy Center Honor medallion, along with a selection of her 13 Grammy Awards, album covers and four illuminating video clips of Ella in performance will also go on view.

After Chick Webb died in 1939, Fitzgerald led the orchestra for two years and then embarked on a solo career. Dizzy Gillespie introduced her to Bebop, and she soon reveled in the wordless improvisation of “scat” singing, enjoying great success with such Decca recordings as “Flying High” and “Oh, Lady Be Good.”

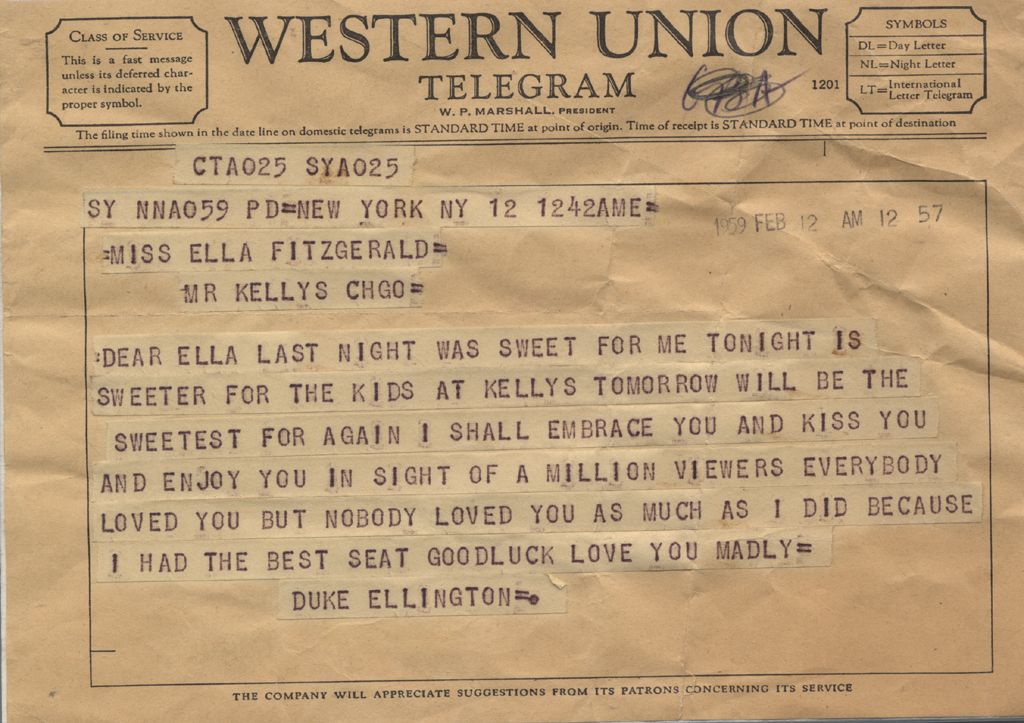

But then her manager Norman Granz convinced her to go in a different direction. In 1956 he signed her to his new Verve recording label and sent her on a worldwide tour with Louis Armstrong and the Duke Ellington and Count Basie big bands. Ella Fitzgerald became a major international star.

The exhibition, says John Edward Hasse, the museum’s curator of American music and founder of Jazz Appreciation Month, tells the story of Fitzgerald’s barrier-breaking career. An iconic 20th-century media figure, she floated effortlessly from Big Band swing in the 1930s, through the scat-singing of Bebop, to her remarkable LPs that showcased the classic American songbook. in the 1950s and ‘60s.

The 1938 Decca recording that launched Fitzgerald’s career is spotlighted in the exhibition. She was a 21-year-old singer with the Chick Webb swing band when Webb became ill in 1938. To cheer him up, she collaborated with the band’s young arranger, Van Alexander, on a musical version of the nursery rhyme “A-Tisket, A-Tasket.”

The band was playing the Flamingo Room in Boston and performed the new song one night for a coast-to-coast radio broadcast. Robbins Music in New York heard about the song and on May 2, the band recorded it for Decca Records. “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” went to Number 1 on the Hit Parade and stayed there for 19 weeks. Ella Fitzgerald’s career was launched.

But as Hasse says, “Who could have predicted at that time that someday she would record a body of work so magnificent—her Songbook series—that it would come to be regarded as a cornerstone of recorded 20th-century popular song?”

Dick Golden, host of the Sirius/XM “American Jazz” program, is enthusiastic about Fitzgerald’s preeminent role in the pantheon of American popular song. He also notes that, while recordings were essential to her career, it was AM radio that broadcast her performances to a wide national audience. Radio was the perfect medium for her voice, ably capturing the youthful radiance and perfect modulation that characterized her sound from the first notes of “A-Tisket, A-Tasket.”

The most important thing that record producer Norman Granz did, says Hasse, was to persuade Ella to record the “songbook” LPs devoted to the classic American works of Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen, Duke Ellington, Rodgers and Hart, George and Ira Gershwin, and Johnny Mercer. In a recent interview, Tony Bennett explained that “her singing interpretation was at such a high level” in the songbooks: “as a performer she was so centered…she really was the ‘Grand Queen’ of all of the singers!”

For jazz broadcaster Dick Golden, the reason these Songbooks are “classic” is that they capture the essential spirit of America’s “one from many” national identity. Written mainly by first or second-generation composers, these songs are the “enduring repertory of America’s immigrant culture,” he says.

Ella Fitzgerald encapsulated this spirit of inclusiveness throughout the arc of her recording career. She recorded nearly 300 songs for the songbook albums, and as lyricist Ira Gershwin once said after listening to the five-LP Gershwin songbook, “I never knew how good our songs were until I heard Ella Fitzgerald sing them.”

“Ella Fitzgerald: The First Lady of Song at 100” will on view at the National Museum of American History through April 2, 2018. Jazz Appreciation Month kicks off March 31 with the Women in Jazz concert. The National Portrait Gallery will display the William Gottlieb image from April 13 to May 14, 2017.

Dick Golden’s “American Jazz” program is broadcast on Sirius/XM radio’s Real Jazz Channel” Saturdays from 10 a.m. to noon (Eastern), and Sunday evenings from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. John Edward Hasse will be his guest April 22 and 23, and Smithsonian Secretary David Skorton will be his guest April 29 and 30.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)