Every year, the American Library Association bestows the Pura Belpré Award to a book writer and illustrator whose work “best portrays, affirms, and celebrates the Latino cultural experience in an outstanding work of literature for children and youth.” Since 1996, the award has brought distinction to history books, biographies, science fiction novels and novellas, with this year’s going to Sal and Gabi Break the Universe by Carlos Hernandez.

Yet Belpré herself deserves recognition.

She was the first Afro-Latina librarian to work for the New York Public Library. Belpré got her start in 1921 at the 135th Street branch in Harlem when she noticed almost immediately that few books written in Spanish were available, despite being needed by the growing population of Puerto Ricans moving into the area.

Nuestra América: 30 Inspiring Latinas/Latinos Who Have Shaped the United States

This book is a must-have for teachers looking to create a more inclusive curriculum, Latino youth who need to see themselves represented as an important part of the American story, and all parents who want their kids to have a better understanding of American history.

“As I shelved books, I searched for some of the folktales I had heard at home. There was not even one,” she would later say. So she wrote a story about the friendship between a mouse and a cockroach; and the 1932 Pérez y Martina became the first Spanish-language children’s book to be brought to market by a major American publisher. She later transferred to the 115th Street library and began to envision the local library as more than just a place for books. To her, it was a community center, where Latino children and adults might come to celebrate their culture and to hear lectures from well-known artists like the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Singlehandly, Belpré spawned a welcoming meeting space for Latinos in New York City in the 1930s. She died in 1982 and her papers are now housed at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York City.

Belpré is now being honored by the Smithsonian Latino Center. “This is somebody's story that needs to be captured,” says Emily Key, the center’s director of education, “because she didn't set out to try to be a barrier breaker. When she started, she saw a need, and she tried to fulfill it.”

Belpré is among the 30 Latinas and Latinos profiled in the new book Nuestra América, 30 Inspiring Latinas/Latinos Who Have Shaped The United States. Published by the Smithsonian Institution via the Hachette Book Group and written by the award-winning Latina news editor and story teller Sabrina Vourvoulias, with illustrations by Gloria Félix, the book is aimed at a young audience, but older readers stand to learn from the significant, and often unrecognized, contributions Latinos have made to the United States. These are the stories of everyday people who served their communities in matter-of-fact ways, as well those of celebrities, scholars, scientists and writers.

Nuestra America aims to deliver short biographies of well-known activists like Dolores Huerta and César Chávez along with stories like that of Sylvia Acevedo, a Mexican-American woman who as a young girl, stared into the night’s sky in awe of the constellations. That awe would lead her to become an engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Acevedo’s story is just as impactful, according to Key, who was on the team that oversaw the book project. “One of the things that you start to realize is some people just are not known,” she says.

And so, the heroic tales of clinical psychologist Martha E. Bernal, airline pilot Olga Custodio, and the indigenous climate scientist Xiuhtezcatl Martínez are interspersed with those of the ball player Roberto Clemente, the actress, singer and dancer Rita Moreno and the playwright and composer Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Key is hoping the book will show young readers, especially young Latino and Latina readers, that they should never feel obligated to follow a pre-ordained path in life. "We wanted very clearly to show that to ‘make it,’ you don't have to be the multibillionaire business person or a doctor,” she says.

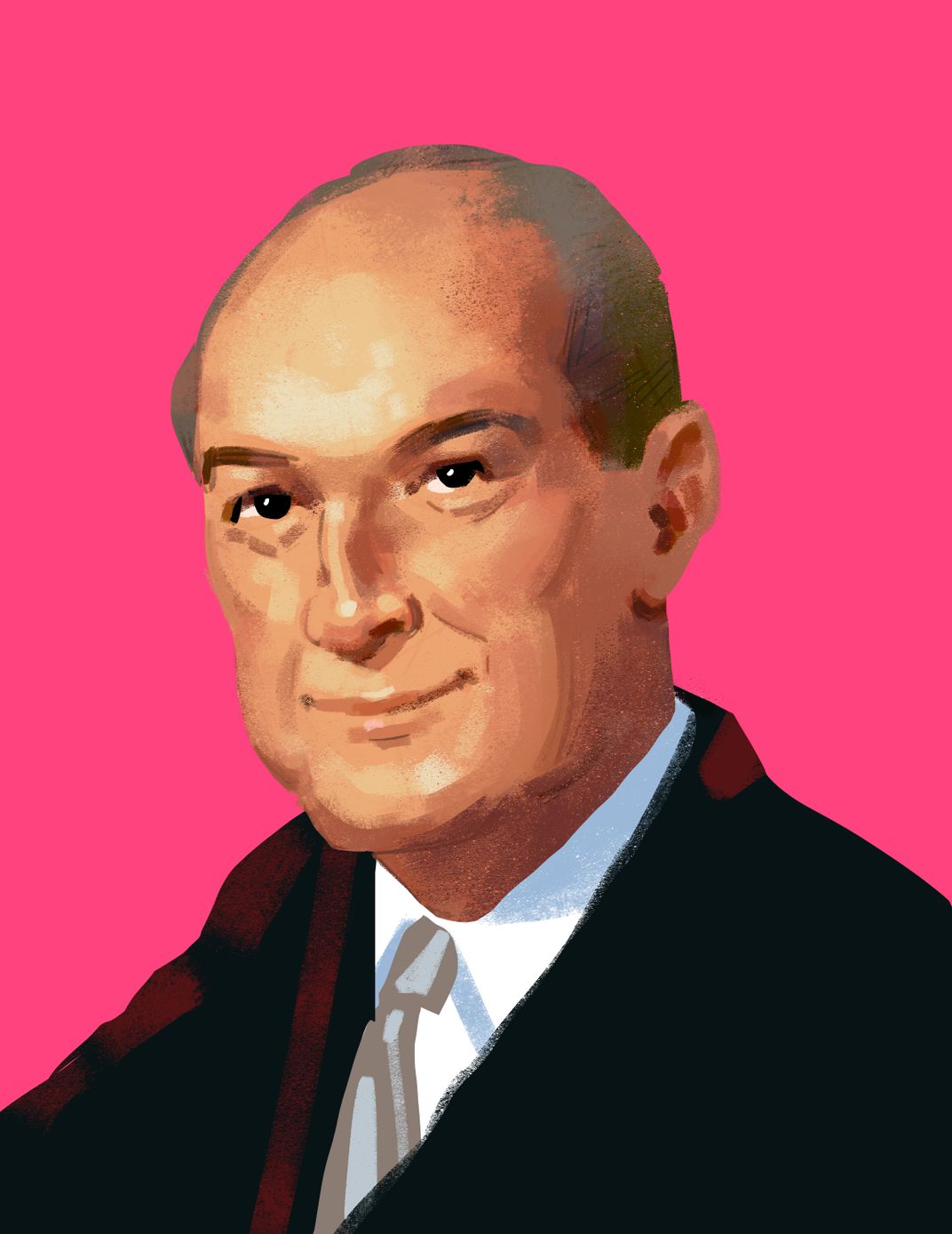

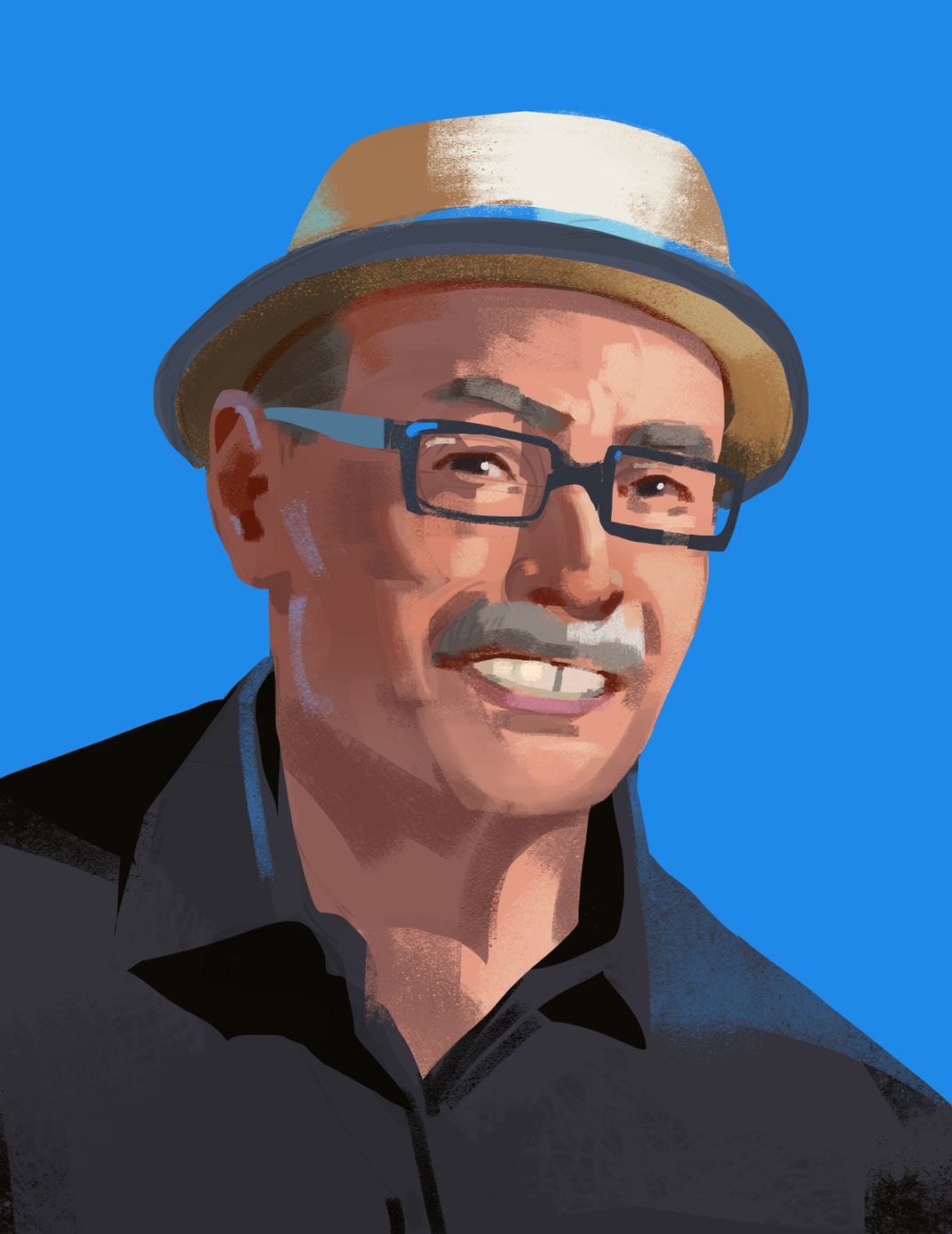

Félix, a Mexican-born artist now living in Los Angeles, endows each of the biographies with a portrait to suit their personalities—played against bright colorful and mural-like backgrounds designed to focus a young reader’s attention. “One of the things that I was so taken with going through the review process was making sure, what kind of personality do you want this illustration to have? Do you want it to be friendly? Do you want it to be warm and inviting? Do you want this to be like they're focusing on their project at hand? Or do you want it to be more like they're having a conversation with you,” Key said.

The cis- and non-binary men women and children featured in the book come from different racial, political and economic backgrounds who by their very existence, undermine the misconception of a monolithic Latino culture in the United States. Emma González, the famous gun control activist is featured as well as the CEO of Goya, Robert Unanue, whose food products are a staple of Latino households, but who recently faced heavy backlash and a boycott by many Latinos angered over his support for President Donald Trump and his administration’s anti-immigration policies.

While Nuestra América gives a broad overview of Latinas and Latinos in the United States, some well-known names are absent from its pages such as the singer and songwriter Selena and U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. “There are a lot of people who will write about Selena. But is somebody going to write about Luis Álvarez, the physicist,” says Key, who says that 100 figures were first proposed and the list was painfully whittled down until 30 were left.

“Our hope is that you will go on to learn about many others in the Latino community,” writes the center’s director Eduardo Díaz in the book’s forward, “who have made and continue to make meaningful contributions to strengthening the fabric of this country.”

The debate about how to go about the book extended into the name itself. Latinx is used occasionally within the text but the subhead uses the traditional term “Latinas/Latinos.”

This is by design, according to Key. “There are sections in the book where we use the term Latinx, because they, the individual themselves, identified as such, but there are many who do not use the term Latinx, because historically, they would not have used that term,” she points out. Nuestra América is a standalone book but it also acts as a supplement to an upcoming project by the Latino Center.

Twenty-three of these individuals will be further featured at the Molina Family Latino Gallery, the Latino Center’s first physical exhibition, which is slated to open at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in the spring of 2022. The exhibition will feature objects, first person accounts and multimedia to tell the story of Latinos. “We wanted to create this Latino family environment in the gallery. . . it stands to reason that the book series that we're looking at is also designed for younger readers. . . what will happen is those learning materials, including the books, will all relate back to the content in the gallery itself,” says Díaz.

Key also sees this as part of the gallery’s education initiative where visitors can sit and read books relating to the project. “We also want to experience the book while you're in the space and experience the content and see itself reflected so there's a lot of cross pollination of the book with the gallery, the gallery with the book,” she says. She remembers the work she and her team did to make this book come to life, reviewing galleys, illustrations and going over the results with her team, all of whom, are people of color. One of her team members said that her own conceptions of Latinos were influenced by mass media. For Key, that meant more often than not, mass media did not make space for people like her or her team members. Now she hopes to help change that with Nuestra America.

As for Díaz, the book, he says, will help to paint a more accurate portrait of our country’s past, present and future; as he points out, “Latino history is American History.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/ea/57ea11fc-86f5-43a9-b14e-aed89aa26791/nueva_america.png)